On Feb. 26, 2022, a group of 14 independent scholars and non-academics from around the world convened the first meeting of the Invisible College to discuss an important book, J.L. Talmon’s The Origins of Totalitarian Democracy, (a 1951 study of the French Revolution that identifies the historical origins and political presuppositions of totalitarian “democracy”). What follows is one, and only one, participants’ take away from the discussion.

I was initially attracted to the book by other things I had read and had written myself. Talmon seemed to “echo” the diagnosis of Gnosticism given by Voegelin in The New Science of Politics (1952), the distinction made by Oakeshott between The Politics of Faith and the Politics of Skepticism (composed in the early 1950s); it reflected, as well, in the French context, the distinction made by Constant between ancient and modern liberty, and, of course, Tocqueville’s observations and warning in Democracy in America.

What I hoped to see vindicated were (1) my own claims on the importance that the misguided notion of a social technology rooted in an alleged social science had originated among pre-revolutionary French philosophes; (2) the well known thesis (Crane Brinton, Voegelin, Hayek, and Oakeshott) that the French Revolution was fundamentally different from the U.S. Revolution; and (3) that the concept of the “rule of law” had a significantly different meaning in the Anglo-American legal inheritance from the Continental legal inheritance. Finally, I wanted to see to what extent our forebodings about the dangers of progressivism especially in its “woke” form exemplified what Talmon would say about “Political Messianism.”

Presuppositions aside, rereading Talmon fifty years later, I discovered two new and related things. First, the transition from classical liberalism (liberals are/were people who want(ed) to limit the power of government over individuals) to modern liberalism (liberals are people who want to increase the power of government over individuals) and beyond (socialism and Marxism) is the product of the misunderstanding or misrepresentation of English liberalism by French philosophes (intellectuals) filtering it through their quite different intellectual tradition. Second, that transition carried to its logical conclusion is the totalitarian democracy we not only saw in Revolutionary France, but is reflected in present day “woke” democracy. It is always worth reminding ourselves and others that rereading a classic in light one’s other and additional readings is almost like reading a new text. The same can be said for sharing one’s personal reading with that of others.

My personal comments are in bold and comments relevant to contemporary America are indicated in italics.

Talmon makes his own epistemological presuppositions very clear. To begin with, he does not believe that it makes sense to talk about human beings independent of their historical, cultural, and socio-economic context. He contrasts this with what he calls rationalism, by which I take him to mean the Cartesian starting point of the Discourse on Method, that is thinking of oneself as the disembodied and context—less observer sitting in judgment of the world from the vantage point of the Archimedian skybox shared only by God (again analogous to Oakeshott’s description of the “rationalist” in the essay, “Rationalism in Politics.” To say that you are a product of your history is not to deny that you may be a product of your conscious rejection of part of your inheritance. Even then we would need to know the history to understand your rejection). As Talmon himself puts it: “Nature and history show civilization as the evolution of a multiplicity of historical and pragmatically formed clusters of social existence and social endeavour, and not as the achievement of abstract Man on a single level of existence” (p. 254).

Ontologically, Talmon insists that the two instincts most deeply embedded in human nature are the yearning for salvation and the love of freedom. The attempt to satisfy both at the same time is bound to result, if not in unmitigated tyranny and serfdom at least in monumental hypocrisy and self- deception which are the concomitants of totalitarian democracy (p. 253).

The Right [conservatism] declares man to be weak and corrupt. The Right teaches the necessity of force as a permanent way of maintaining order among creatures, and training them to act in a manner alien to their mediocre nature. Not everyone on the right advocates totalitarianism, but totalitarians of the Right operate solely with historic, racial and organic entities, concepts altogether alien to individualism and rationalism.

Totalitarianism of the Left, when resorting to force, does so in the conviction that force is used only in order to quicken the pace of man’s progress to perfection and social harmony: It is thus legitimate to use the term democracy in reference to totalitarianism of the Left. The term could not be applied to totalitarianism of the Right.

Modern communism is much more than distributive socialism. It advocates “an exclusive social pattern based on an equal and complete satisfaction of human needs as a program of immediate political action.”

That imagined repose is another name for the security offered by a prison, and the longing for it may in a sense be an expression of cowardice and laziness, or the inability to face the fact that life is a perpetual and never resolved crisis (p. 255).

Two other works exemplify what Talmon has in mind. First, Eric Hoffer’s The True Believer, also published in 1951, maintains that extremist cultural movements occur when large numbers of lost souls who think that their own individual lives are worthless join a movement demanding radical change. What motivates them is the desire to escape from the self, not a realization of the self. “A mass movement attracts and holds a following not because it can satisfy the desire for self-advancement, but because it can satisfy the passion for self-renunciation” (p. 21). The resentment of the weak does not spring from any specific injustice but from the sense of their inadequacy. The resulting self-loathing produces serious social disruption.

Second, Michael Oakeshott’s 1962 essay, “The Masses in Representative Democracy” identifies Anti-Individuals as those who yearn for a protective community which takes care of them and relieves them of the anxiety of making choices; “there were some people, by circumstance or by temperament, less ready than others to respond to this invitation [to become autonomous]”. There were no anti-individuals before the Renaissance, only members of a community. Once some people become autonomous individuals but others do not, those who do not make the transition become anti-individuals. Anti-individuals are a reaction against autonomous individuals. They are resentful of autonomous individuals, display “envy, jealousy, resentment.” They need a leader; and they want uniformity, equality and solidarity. They blame autonomous individuals for the anxiety, want to destroy the prestige of autonomous individuals and make everyone an anti-individual.

This is the curse of salvationist creeds: to be born out of the noblest impulses of man, and to degenerate into weapons of tyranny. An exclusive creed cannot admit opposition. It is bound to feel itself surrounded by innumerable enemies. Its believers can never settle down to a normal existence. From this sense of peril arise their continual demands for the protection of orthodoxy by recourse to terror. Those who are not enemies must be made to appear as fervent believers with the help of emotional manifestations and engineered unanimity at public meetings or at the polls [vote as a block].. Political Messianism is bound to replace empirical thinking and free criticism with reasoning by definition, based on a priori collective concepts which must be accepted whatever the evidence of the senses : however selfish or evil the men who happen to come to the top, they must be good and infallible, since they embody the pure doctrine and are the people’s government: in a people’s democracy the ordinary competitive, self-assertive and anti-social instincts cease as it were to exist (p. 253).

In this work, Talmon is primarily interested in the shaping of the religion and myth of Revolutionary political Messianism (p. 231).

The Two Types Of Democracy: Liberal And Totalitarian

The liberal approach assumes politics to be a matter of trial and error, and regards political systems as pragmatic contrivances of human ingenuity and spontaneity. It also recognizes a variety of levels of personal and collective endeavour, which are altogether outside the sphere of politics. [Anglo-American conception; think Hume’s History of England; liberal practices preceded liberal theorizing.]

The totalitarian democratic school, on the other hand, is based upon

- The assumption of a sole and exclusive truth: it postulates a preordained, harmonious and perfect scheme of things, to which men are irresistibly driven, and at which they are bound to arrive.

- It recognizes ultimately only one plane of existence, the political. It widens the sense of politics to embrace the whole of human existence.

- In so far as men are at variance with the absolute ideal they can be ignored, coerced or intimidated into conforming, without any real violation of the democratic principle…The practical question is, of course, whether constraint will disappear because all have learned to act in harmony or because all opponents have been eliminated.

- Everything is politicized [names on cereal boxes, professional sports teams, pandemics, etc.]

- The postulate of some ultimate, logical, exclusively valid social order is a matter of faith, and it is not much use trying to defeat it by argument.

Part I: The Eighteenth-Century Origins Of Political Messianism

- There was a fundamental principle in pre-eighteenth century chiliasm that made it impossible for it to play the part of modern totalitarianism: its religious essence. This explains why the Messianic movements invariably ended by breaking away from society, and forming sects [e.g. Benedict Option] based upon voluntary adherence and community of experience. They aimed at personal salvation and an egalitarian society based on the Law of Nature, and believed that obedience to God is the condition of human freedom.

- With the rejection of the Church, and of transcendental justice, the STATE remained the sole source and sanction of morality.

- The strongest influence on the fathers of totalitarian democracy was that of ANTIQUITY interpreted in their own way. Their myth of antiquity was Libertya (autonomy of the whole society not the individual) equated with virtue (ascetic discipline)

- The idea of man as an abstraction, independent of the historic groups to which he belongs, is likely to become a powerful vehicle of totalitarianism.

- Modern Messianism has always aimed at a revolution in society as a whole. The point of reference is man’s reason and will, and its aim happiness on earth arrived by a social transformation.

[Allow me to interject here some observations from the modern scientific revolution. There were two competing models: Newtonian and Cartesian. In Newtonian physics, the first law states that individual objects move in a straight line at a constant speed forever (infinitely) in empty space or the void – clear analogue to Hobbesian desire; Newton also believed that the universe required God’s periodic intervention. In Cartesian physics, there is no empty space but a plenum within which every body touches other bodies and a vortex within which such bodies move harmoniously. If the speed and position of all the bodies could be completely described, then all future permutations could be deduced through calculations based on the laws of motion. The social analogue to Cartesian physics is a natural harmony.]

The object of Talmon’s book is to examine the three stages through which the social ideals of the eighteenth century were transformed-on one side-into totalitarian democracy (According to Hoffer, “a movement is pioneered by [1] men of words, [2] materialized by fanatics, and [3] consolidated by men of action.” (p 147 of The True Believer):

1. The eighteenth-century postulate (Rousseau’s “General Will”); Rousseau’s starting point, as Kant noticed, was the individual free will – not a pre-existing collective entity. Herein lies the contradiction between individualism and ideological absolutism inherent in modern political-Messianism.

As a systematic philosopher, Descartes (this discussion of Descartes appeared in a previous edition of The Postil) introduces and makes the official starting point of modern epistemology the “I Think” perspective, something that had been implicit in classical and medieval thought. Classical thought had always prioritized thought over action or practice. It had always presumed that we needed an independent theory before we can act. Prior to Descartes, skeptics had repeatedly exposed the plurality of mundane competing theories. Drawing on the Augustinian inheritance of the school he attended at La Fleche, Descartes thought he could permanently dispose of skepticism by practicing the Socratic Method on himself and drill down until he found what could not be questioned/challenged without self-contradiction. This method did not rely on any appeal to our bodily experience of the world – which might after all be an illusion. Nor did it appeal to any social framework: tradition, customary practice, which were after all potentially illusory historical products.

Having established thereby to his own satisfaction that he existed as an “I Think,” Descartes proceeded to establish the existence of God. Whereas Aristotle had identified four causes, wherein three of which (formal, final and efficient) were identical, Descartes eliminated final (teleological) causation. Nevertheless, Descartes retained the identity of formal and efficient causation. This alleged identity permitted one to argue backwards from any effect (form) to its efficient cause sight unseen. Given Cartesian physics and traditional logic, this is an unassailable proof of God’s existence as creator or first efficient cause of the physical world and ultimate author of the Bible! Thus, had Descartes established the existence and validity of the Christian world- view (hereafter the “PLAN”) now understood as including the transformation of the physical world.

In order to make sense of the Technological Project, the transformation of the physical world in the service of humanity, it is important that some aspect of humanity be independent of the physical world. If humans were wholly part of the physical world, then any human project could be transformed as well, thereby leaving all projects without an autonomous status. Hence, it is necessary that the subject, or at least the mind of the subject, be free and independent of the body.

Modern science did not come to a halt with Cartesian physics and analytic geometry. Newtonian atomistic physics moving in the void of calculus took its place. Now there were only efficient causes. There were no final and no formal causes. There were no necessary connections among different kinds of causes. Hume merely spelled out the implications of Newtonian physics for delegitimizing the alleged proofs of God’s existence (see Capaldi on this).

Still, we had the increasingly clear vision of an orderly Newtonian physical world and the ancillary successes of the Technological Project.

Even with a marginalized or superfluous God, God’s PLAN for the physical world still seemed to be safe. It was so safe it did not seem to need miraculous intervention (Deism). Miracles were replaced by utopian visions of future techno-science. Unfortunately, those who continued to tie God’s Plan to a belief in God could not agree, and they further discredited themselves by engaging in (17th-century) religious wars.

We might learn to do without God, but we sorely needed something like His plan for the social world. In the eighteenth century, some of the French philosophes (Helvetius, d’Alembert, Condorcet, La Mettrie, etc.) proposed the Enlightenment Project: a social science to discover the analogous structure of the social world and an analogous social technology to implement its benefits; a wholly secular plan of ideal harmony without religious warranties. This was an even greater gift to the discipline of philosophy, the opportunity to discover, articulate and implement the secular social PLAN. ‘Modern’ Liberalism, socialism, and Marxism are expressions of the Enlightenment Project. Comte was the master-planner. Needless to say, none of these secular plans has worked, and you could make the case that they made the social world worse off.

However, if there is no God who guarantees the PLAN, why think there is any kind of PLAN? There might even be some kind of predictable order but why think the order is disposed toward human benefit? The physical scientists keep changing the description of the physical order and the alleged social scientists offer thinly veiled private agendas.

J.J. Rousseau comes to the rescue. There is no plan, nothing for reason to discover. All alleged plans are rationalizations of the status quo by its beneficiaries involving the exploitation of the victims. The most we can hope for is to recover our lost innocence, the world before the “Fall.”

In place of an autonomous reason, we find an autonomous will that does not know avarice, shame, or guilt. The autonomous self is pure free will. This primacy of will is not only independence from the body but it is independent of a suspect and instrumental reason. We can achieve a pure social harmony simply by willing the community into existence and outlining the conditions that will sustain it. Those conditions are the alleged condition of the ideal ancient world, a world of roughly equal small farmers in an agrarian community.

2. The Jacobin improvisation (Robespierre and St. Just)

3. The Babouvist crystallization; all leading up to the emergence of economic communism on the one hand, and to the synthesis of popular sovereignty and single-party dictatorship on the other. Property: the bourgeois struggle against feudal privilege was transformed into the proletarian demand for security. [Equality before the law and of opportunity become equality of result]

Many of us have been concerned about (a) the ‘deterioration’ of classical liberalism into modern liberalism (socialism, Marxism) and (b) the evolution of the latter into woke culture and worse. It is my claim that Talmon’s thesis in Totalitarian Democracy explains both as the result of the French Enlightenment (especially Cartesianism and Rousseau) misunderstanding of English liberalism in the 18th-century or its transposition into a French intellectual context. Given my own scholarship you can see why I would agree.

Curiously, it was the Francophile Englishman Bentham who took the French misrepresentation of historic English liberalism, something Bentham dismissed along with English jurisprudence, turned it into the abstraction of utilitarianism, and fed it back into the Anglo-American context. As Hayek pointed out, it was Bentham who introduced into Britain the desire to remake the whole of her law and institutions on rational principles.

Dicey, in Lectures on the Relation Between Law and Public Opinion in England During the Nineteenth Century, claimed that Bentham was responsible for turning liberalism from a protection against outside interference into government intervention (social technology). “The patent opposition between the individualistic liberalism of 1830 and the democratic socialism of 1905 conceals the heavy debt owed by English collectivists to the utilitarian reformer. From Benthamism the socialists of to-day have inherited a legislative dogma, a legislative instrument and a legislative tendency…. The dogma is the celebrated principle of utility.”

Almost all of subsequent political philosophy in the Anglo-American world (including libertarianism, classical liberalism, modern liberalism, socialism, and Marxism) has been a reflection of Bentham’s wrong turn, and, I would argue has been an enabler of the gradual deterioration of liberty.

Chapter 1: Natural Order

Natural Order lays out what I have called the Enlightenment Project by examining the works of Helvetius, Holbach, Condorcet and Morelly’s Code de la Nature. This was a clear deviation from Montesquieu’s policy of looking for previous historical French practice. Condorcet specifically criticized the U.S. for being evolutionary instead of revolutionary.

Chapter 2: The Social Pattern and Freedom

The “General Will” is a Cartesian concept—everyone can discover it with the right method. Hence, education has political implications that are totalitarian: you are not free to deny, ignorantly, or undermine the General Will. The Individual gives way to the legislator.

Chapter 3: Rousseau

[General will = what we would all want if we had all the information and interpreted it correctly; since it is something we “will” we can choose to make it universally harmonious and absorb the total cost no matter what the consequences or unintended consequences.]

The General Will allows Self-consciousness to become social consciousness [Comte, the founder of sociology, will assert subsequently that the advance of science leads to the substitution of a “We think” epistemology for an “I think” epistemology, and therefore to the discovery of social laws.]

The General Will morphs into the idea of a classless society. [Whereas, Hume and Smith posited sympathy as a way we could understand the “other,” for Rousseau sympathy permits a complete identification with the other or the subsumption of self-interest into social interest]. The political implication is that we do not need representatives of individual and factional interests but leaders who understand the people as a collective whole (do away with the Senate, with the electoral college, with the filibuster).

[Allow me to interject here. One of the perennial concerns within advocates of liberal thought has been the historical transition from classical liberalism (protect the individual from government control) to modern liberalism (all rights come from the government). This transition and the further transition from liberalism to socialism/Marxism is precisely what Talmon is addressing and explaining. The explanation of the transition is the failure to understand that classical liberalism is the product of historical practice and not theory. You cannot theorize practice or theorize the relation of theory to practice because there is no underlying structure or social laws.

This is exactly what led J.S. Mill, an early fan of Comte, to condemn Comtism as a form of totalitarianism. Moreover, the attempt to provide a ‘theory’ of liberalism inevitably leads to the postulation of clever abstractions from which anything can be derived or rationalized. Once anything goes, the door has been opened to utopianism, messianism, to fraud, to the self-serving pretense of expertise, the rationalization of the worst human excesses, etc.

Perhaps the most interesting example of all this is the most boring and overrated book on political thought produced in the last half of the 20th-century, Rawls’ A Theory of Justice. Rawls thought he was theorizing liberalism – of whose history he was ignorant—by imaging a thought experiment in which we ignore everything that is true of individuals and focus only on what is allegedly true of all of us—assuming it to be harmonious. Does this sound familiar? It’s Rousseau Deja vu. Rawls convinces himself that this leads to the priority of liberty only to find that his book has become the celebrated classic of socialism. See, for example, Piketty. Rawls expiated his guilt by writing a later book Political Liberalism but the damage had been done and nobody cared or listened.]

Chapter 4: Property

Rousseau and others believed in some quite limited form of private property and none foresaw the tremendous increase in wealth that would be created by the industrial revolution. At this time, Morelly was the only consistent communist foreseeing an egalitarian social harmony thru state-controlled asceticism. We should all learn to live on less [and perhaps make sacrifices for the environment].

[One of the things that has forestalled the growth of socialism has been the vast improvements in the standard of living since the last half of the 19th-century. Socialism gets a new lease on life with the advent of alleged threats to the climate by pollution.]

Part II: Jacobin Improvisation

Chapter 1—Revolution of 1789—Sieyes. Talmon reiterates his contention on the replacement of tradition by abstract reason (p. 69): “There is no respect in this attitude for the wisdom the ages, the accumulated, half-conscious experience and instinctive ways of a nation. It shows no awareness of the fact that truly rationalist criteria of truth and untruth do not apply to social phenomena and that what exists is never the result of error, accident or vicious contrivance alone, but is a pragmatic product of conditions, slow, unconscious adjustment, and only partly of deliberate planning” (p. 71). [A tradition or an inheritance is a fertile source of adaptation- Oakeshott].

Sieyes criticized the British Constitution as a gothic superstition. He reflected the contradiction between: an absolutist doctrinaire temperament, revolutionary coercion, egalitarian centralism, a homogeneous nation vs. Lockean private property.

Chapter 2—Robespierre exemplifies the psychology of the neurotic egotist who must impose his will or wallow in an ecstasy of self-pity. He was led to believe that the General Will needs objective truth embodied in the enlightened few to which the actual count of votes takes second place. [Rigged elections may better reflect the “General Will”?]

Chapter 3—Road from democracy to tyranny by way of the totalitarian -democratic vanguard in a plebiscitary regime.

Anglo-American liberty: defend personal freedom from government; French: defend revolutionary government from factions; Create the conditions for a true expression of the popular will; Outlaw political parties => one party.

Redefinition: Liberty = a substantive set of values and not just the absence of restraint = equality in fraternity [liberty, equality, and fraternity]. Denunciation of those who disagree or criticize [canceled] and a ban on the slightest difference of opinion and sentiment.

[Since the “general will” is something we ‘will’ and is not a discovery or an alleged truth that can be refuted or disconfirmed, any fact that is incompatible with the ‘general will’ must be censored in the interest of social harmony—think Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four]

Chapter 4—Saint Just.

Chapter 5—The Social Problem.

Basic inconsistency on private property.

THE great dividing line between the two major schools of social and economic thought in the last two centuries has been the attitude to the basic problem: should the economic sphere be considered an open -ended human initiative, skill, resources, with the State intervening only occasionally to fix the most general and liberal rules of the game, to help those who have fallen by the wayside, to punish those guilty of foul play and to succour the victims thereof; OR should the totality of resources and human skill be ab initio treated as something that should be deliberately shaped and directed, in accordance with a definite principle; could men be educated in a socially integrated system as to begin.to· act on motives different from those prevailing in the competitive system?

Robespierre and Saint-Just felt themselves moved to integral planning in accordance with a definite principle—the idea that the needs of the poor were the focus and foundation stone of the social edifice [woke focus on African Americans, women, and gender issues.]

Babeuf and nineteenth-century successors of Jacobinism up to 1848, was in its defiant tone—new and upon a totally different plane from the right to [pursuit of] happiness of Locke and the fathers of the American Constitution, as well as from the right to social assistance. Equality—limit amount of property, abolish bequest; everyone works.

Part III: The Babouvist Crystallization

Chapter 1: Lessons of the Revolution

No social peace between the two classes was possible. Babeuf embodied:

- Deep personal misery

- Messianic longings

- Passion for self-dramatization

- Intoxicated with words

- The declasse

Philipe Buonarroti—high priest of egalitarian communism in Europe.

Chapter 2: Babouvist Social Doctrine

- The state and not the unfettered mind of the individual is the source of social as well as moral progress.

- Paradox: individualist basis of the collectivist philosophy.

- Logically: [Cartesian] starting point should be an a priori principle or some purpose outside and above man’s will [Rousseau].

- History: the moment of the violation of original equality (acquisitive spirit) and restoration at some preordained future hour.

- Refusal to see the desire to increase wealth as an impulse for a higher culture; wealth is never a reward for merit.

- Existing society is a superstructure deliberately built by avarice to secure a reign of pillage.

- Merchants are engaged in a permanent conspiracy against the consumer class.

Silent civil war: (Bourgeois and aristocratic Republic vs. popular and democratic Republic). Call for a general strike to paralyze society [riots?].

French Revolution is the beginning of an apocalyptic hour in mankind’s history [tear down statues]. It reduces the standard of living by persuasion [climate change]. Destroys personal ambition. No police or prisons or trials (p. 195). [Woke Agenda: cancel culture, indoctrination (masks?), participation trophies, no grades, affirmative action, no cash bail, etc.]

Chapter 3: The Plot.

The Left had no proper organization [it never does and hence falls prey to gangsters; Stalin assassinates Trotsky, etc. Talmon, Hoffer, and Oakeshott all distinguish between those who are recruited as the ‘downtrodden’ and those who are the leaders or spokespersons for the ‘downtrodden’. Hoffer describes them as having “the vanity of the selfless, even those who practice utmost humility, is boundless” (p. 15); Oakeshott maintains “the task of leadership … what his followers took to be a genuine concern for their salvation was in fact nothing more than the vanity of the almost selfless”.]

Chapter 4: Democracy and Dictatorship

- Constitution “would be framed in such clear, detailed and precise definitions that no diverse interpretations, sophisms, ambiguities or caviling would be possible” (p. 201). [You cannot construct an artificial language without using an historical natural language; you cannot introduce a new set of practices without presupposing the old practices; reinforces Talmon’s point that the human/social world cannot be understood independent of its history; replacing the past requires either a knowledge of the past or a misunderstanding or misrepresentation of the past.]

- Poor have no time or wealth to attend meetings or get information [or voter ids]

- Democracy is a stage beyond republicanism [democracy is not a procedural norm but a substantive norm—hence all those people who precede the word with an adjective]

- Babeuf evolves from a believer in reconciliation to a partisan of class struggle

- Plebiscitary, direct democracies the precondition of dictatorship or dictatorship in disguise; full unanimity = imposition of a single will = part of the vanguard [imagine the US with all voting done without parties and directly through individual computers serviced and counted by Silicon Valley]

- Vacillate between violent coup OR educate the masses

- Eliminate opposition and engage in intensive education and propaganda [Facebook]

- FORCE CANNOT BE ELIMINATED

Chapter 5: Structure of the Conspiracy

Masses were to be won over by distribution of spoils (p. 228) – [encouraged and allowed to sack stores in downtown shopping district]

Chapter 6: Ultimate Scheme

Unanimity, spiritual cohesion, and economic communism

- Babavoist: virtue, democracy, and communist equality

- Certificate of “civisme” (p. 234) to participate [Chinese evaluation of individual citizens]

- Zbigniew Brzeziński, former national security advisor to President Carter, put it in his 1968 book, Between Two Ages, America’s Role in the Technotronic Era: “The technetronic era involves the gradual appearance of a more controlled society. Such a society would be dominated by an elite, unrestrained by traditional values. Soon it will be possible to assert almost continuous surveillance over every citizen and maintain up-to-date complete files containing even the most personal information about the citizen.”

- Immense body of civil servants

- Evils that flow from refinement in the arts

- No claim for pre-eminence

Arts and science become social functions and instrument for evoking collective experiences [academy awards on TV].

Conclusions

“All the emphasis came to be placed on the destruction of inequalities, on bringing down the privileged to the level of common humanity [wealth tax; opposition to the flat tax; Obama’s statement that “you did not build that”], and on sweeping away all intermediate centers of power and allegiance, whether social classes, regional communities, professional groups or corporations. [eliminate parental input into public education; outlaw home schooling]. Nothing was left to stand between man and state” (p. 250).Two policies: repression of those who objected and re-education

This is an extreme individualism: [individuals behind Rawls “veil of ignorance”]—individuals without history. The Intellectual as rootless cosmopolitan. [Destroy the history and then re-educate within the new mythos; 1619 Project.]

Political Messianism spent itself in Western Europe soon after 1870 and then moved to its natural home in Russia (generations of repression and the pre-disposition of the Slavs to Messianism).

Volume II: 19th century Europe, Volume III: 20th-century Europe [Talmon did not foresee in the 1950s the resurgence in the Western World.]

Addendum: Tocqueville

Equality and freedom do not develop in a proportional relationship. Especially in a democratic society, “Among these nations equality preceded freedom; equality was therefore a fact of some standing when freedom was still a novelty; the one had already created customs, opinions, and laws belonging to it when the other, alone and for the first time, came into actual existence. Thus the latter was still only an affair of opinion and of taste while the former had already crept into the habits of the people, possessed itself of their manners, and given a particular turn to the smallest actions in their lives.”

Therefore, although people in democratic countries love freedom by nature, their passion for equality is even more difficult to stop. “they call for equality in freedom; and if they cannot obtain that, they still call for equality in slavery.” It is precisely because of his admiration of freedom that Tocqueville inherited Constant’s idea that the democratic system may be transformed into a tyranny of despotism, and described it as “Tyranny of the majority”. In his opinion, the dangers that democracy can produce are: on the one hand, there is the tendency of anarchism, which has been widely discussed; on the other hand, the tyranny of the majority, [or as Mill would say those who claim to speak on behalf of the majority]; that is, the stifling of individual freedom by absolute authority. Compared with the former, the latter is more severe.

Tocqueville believes that autocracy is what scares people the most in the democratic era. How to effectively guarantee freedom in a democratic society is the core issue of Tocqueville’s American democratic outlook. Combined with the actual investigation of American society, he proposed to implement a series of measures such as federalism, separation of powers, local autonomy, and freedom of the press in a democratic society to ensure freedom and prevent Tyranny of the majority.

In the Anglo-American world since he 18th-century it used to be the case that the press was a place where public opinion in all of its varieties could be voiced. French intellectuals have always believed that it was their responsibility to form or to construct public opinion.

Nicholas Capaldi is Professor Emeritus at Loyola University, New Orleans.

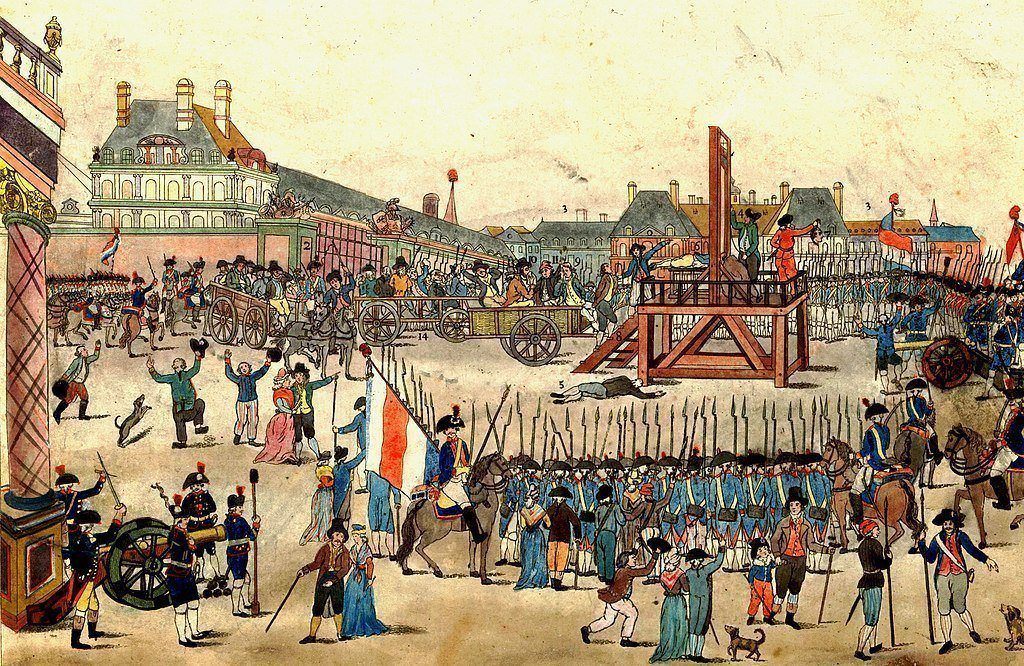

Featured image: “The execution of Robespierre and his supporters on 28 July 1794.” Artist unknown.