We don’t know much about the Synod, because we’re not directly involved. We’re out in the field, patiently ploughing through parish life and “smelling the sheep.” We pick up a few scattered rumblings, which are generally met with indifference; but for some they fuel a vague concern, for others the hope of reforms concerning the place of women or the end of a supposedly “rigid” morality. The advent of a “synodal” Church is also presented, at least implicitly, as a response to the crisis of sexual abuse committed by certain clerics. One of the unstated aims of the “synod fathers and mothers” seems to be to deconstruct the authority of the pastor in favor of collective “decision-making processes,” which would destroy the seeds of clericalism, seen as the root of all evil.

To constantly evoke the dangers of clericalism in an almost totally de-Christianized world and a Church bereft of priestly vocations, which has seen a spectacular drop in the last decade (for Paris, the number of seminarians has fallen by over 50%)—isn’t this just shooting point-blank into what’s left of our feet to walk on? We’d like to hear words about the beauty of the priesthood, implore the Lord to send laborers into His harvest, and pray that priests will be good servants of God’s people, rooted in the interior life. ” Let no evil talk come out of your mouths, but only what is useful for building up, as there is need, so that your words may give grace to those who hear,” says the Apostle (Eph 4:29). Priests, especially the younger ones, need so much encouragement and consolation in the trials of ministry.

The least we can say is that this synod is not arousing the enthusiasm of fervent young Catholics, who attended very little of the preparatory phase. In Paris, only 14% of participants were between the ages of 20 and 35. The figure speaks for itself. Young people have a thirst for identity and clarity, a desire for formation and a certain flexibility in expressing their sensibilities. They go from the Christian pilgrimage to the Mission Congress, from the Gloria of the Angels to an evening of praise and healing.

In his homily at the opening Mass of the Synod on October 4, which was overshadowed by his responses to the dubia and its many possible interpretations, Pope Francis tried to strike a balance. He wants to avoid making debates over controversial issues too tense, and dismisses both the temptation of “rigidity” and submission to an “agenda dictated by the world.” The Synod is called upon, says the Holy Father, to build “a Church that has God at its center and that, consequently, is not divided internally and is never harsh externally.” He warns against “an immanent gaze, made up of human strategies, political calculations or ideological battles.”

The Church is Not Her own Creator

It’s obvious that behind the scenes at synods and conclaves, worldly strategies, intimidations and seductions are all around us. This is the way of man, and even more so of the ecclesiastical world, which is easily covered by a veneer of Roman charity and unctuousness. We can only agree with the Holy Father’s desire for unity. This does not prevent us from reflecting and offering constructive criticism. “You can take off your hat in church, but not your head,” said Chesterton. Cardinal Fernandez accuses those who criticize the “doctrine of the Holy Father” of heresy and schism (National Catholic Register, Sept. 8, 2023). Strictly speaking, there is no “doctrine of the Holy Father,” but the Catholic faith revealed in Jesus Christ, of which we are the servants and not the masters, whatever the orientations of a pontificate.

Basically, things are simple. Does the truth about faith and morals, the fundamental structure of the Church, the sacramental life, the final ends, emanate from “below,” through a democratic dialogue supposedly “in the Holy Spirit” that finally reaches a consensus? Or is it to be accepted “on our knees” by the Revelation of a demanding love that surpasses us, transmitted in fullness by Christ and borne by the living tradition of the Church, by those who have borne witness to the faith at the price of their blood? The Church is not the creator of herself, and we don’t have to define our own moral criteria, but listen to the Lord’s Law. “Be holy, for I am holy”, says the Lord (1 Pet 1:16).

Nonetheless, it’s true that new issues are constantly arising in the parish, and that they are growing in scope, and that the Church can’t ignore them. For example, the number of “remarried” divorcees, some of whom claim the right to receive Holy Communion, invoking “the spirit of Pope Francis;” homosexual “couples” who ask baptism for an adopted child or a child born through MAR; engaged couples, almost all of whom live in a form of cohabitation; the ignorance, for many who knock on the Church’s door, of the most elementary foundations of catechesis. Priests ordained for a traditionalist community generally have the grace of being surrounded by trained, culturally homogeneous faithful who take care of them and don’t question the Church’s constant teaching. A priest in a de-Christianized parish, following decades of “inclusive” pastoral care based on an unconditional welcome that strives to avoid any “cleavage,” and focused more on the charitable pole than on catechetical formation, doesn’t have the same support. The Church needs all kinds of people. Pastors who take care of families anchored in the faith, and others who are more on the front line in the shifting sands of a “liquid” society where the Church is trying to make its way along a difficult path that rarely avoids trial and error, pitfalls or lapses in judgment.

What Catholic, what bishop, would not be preoccupied by concern for all souls? How much hidden sufferings, buried guilt and wounds we must encounter by listening to and soothing, just as the Good Samaritan poured oil and wine on the man’s wounds and led him to the inn: the image of the Church? But to love all men is also to show them, as they grow, the way to a demanding and holy life in line with the objectivity of goodness.

Don’t Try to Legislate Everything

Rome must leave it up to the pastors in the field to discern the best path to take in the face of the particular cases that arise, and avoid at all costs trying to legislate everything, at the risk of falling into unbearable casuistry and aggravating divisions. The pastoral charity of a parish priest strives to reach out to people in complex or objectively sinful situations, but “love and truth meet” (Ps 84). Giving milk does not mean renouncing solid food, still less maintaining the vagueness of revealed truths, at the risk of creating extreme confusion. Loving all people means recalling their vocation to holiness.

The wisest thing to do is to do good where we are, to keep our spleens in check, and to continue teaching the faith of the Church, taking care of the sheep where they are, with as much pastoral delicacy as possible, but never giving up on leading them to the holy mountain which, as priests, we must climb first in a tireless conversion. Not primarily that of reforming structures by initiating ecclesial “processes,” but that of a heart resolutely turned towards the Lord. Conversion is personal, or it is not. The rest will pass like snow in the sun, and the mountain may simply give birth to a mouse. Let’s hope it doesn’t nibble away at the threads that bind us to the long tradition that comes down to us from the Apostles, and that it leads us to take one more small step towards the Lord of life, who remains eternally, beyond the contradictions of mankind, Master of time and history.

Father Luc de Bellescize is the Curate of Saint Vincent-de-Paul in Paris. This article comes through the kind courtesy of La Nef.

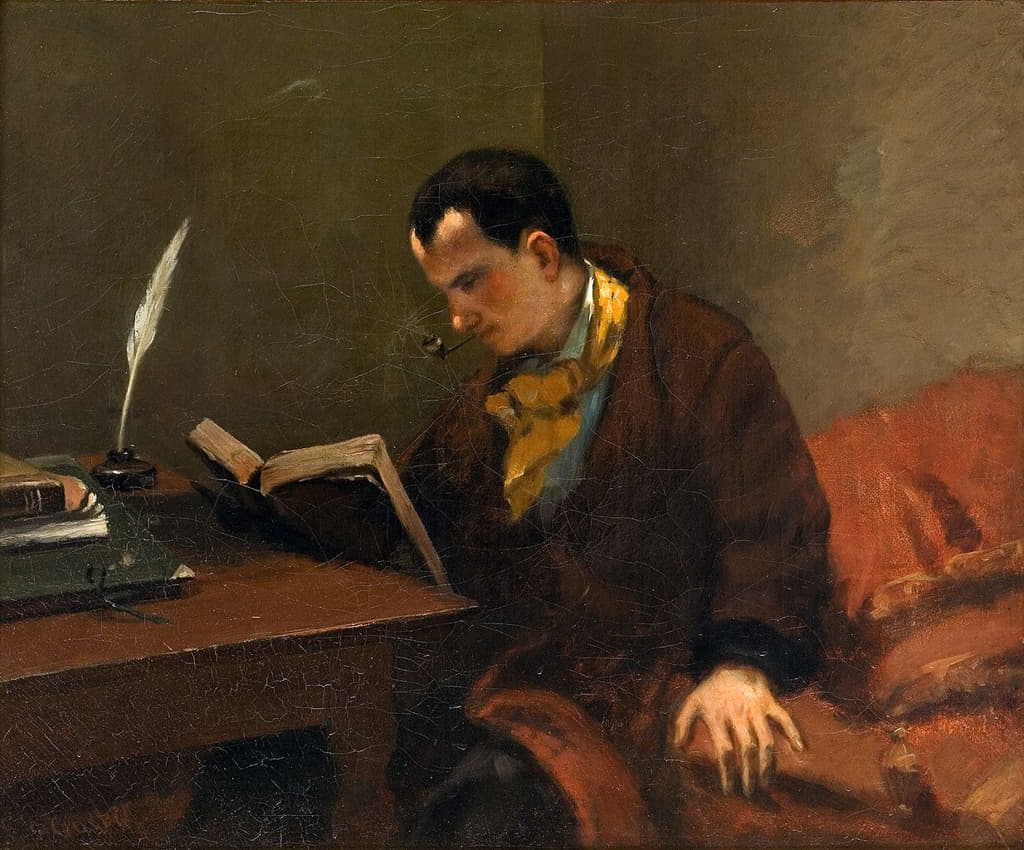

Featured: Fridolin Assists with the Holy Mass, by Peter Fendi; painted in 1833.