Baudelaire died just over 150 years ago, having received the sacraments of the Church. It would be short-sighted to see him only as a hashish-smoking debauchee, a dandy crushed by ennui, an heir who squandered his fortune. If he took on to his very core the darkness of a world without hope and stirred up “the infamous menagerie of our vices,” he has nothing in common with the bourgeois who quietly confesses his atheism. It is worth rereading the contempt with which he holds, in Pauvre Belgique! the “prêtrophobes” and freethinkers who have stunted the scope of the world by extirpating from the conscience any idea of divine retribution: “Having imagined suppressing sin, the freethinkers thought it ingenious to suppress the judge and abolish punishment. This is exactly what they call progress.”

There is something prophetic in his denunciation of a soulless life, where everything is bought and sold. In this sense, Baudelaire is an anti-bourgeois, an “anti-modern” in the line of the Psalms: “And man when he was in honour did not understand; he is compared to senseless beasts, and is become like to them… They are laid in hell like sheep: death shall feed upon them.” (Ps 48:13;15). He could have written Nietzsche’s words, which mock the health-idolatry of the pagan world: “We have our little pleasure for the day, our little pleasure for the night, but above all we revere health.” Houellebecq also participates in his spirit when he writes: “I am a Catholic in the sense that I show the horror of the world without God.” The poet’s restless soul has something of the mystical about it, like an inverted kinship. He responds to the allure of the Divine by probing his own abyss. “His poetry of unrepentant supplication was so sacrilegious that it became, by antinomy, suggestive of adoration,” writes Bloy in Un brelan d’excommuniés.

He pursues an “unknown God,” masked and versatile, who gives “suffering / As a divine remedy to our impurities” (Bénédiction). Bloy wrote of him that he “was a reverse Catholic, like the demons who ‘believe and tremble’ according to the words of Saint James” (James 2:19).

Like Augustine, Baudelaire had a restless heart. He was implacably lucid on man’s lies, on wounded nature, on the ambiguity of beauty, whose gaze is at once “infernal and divine.” He scrutinized “to the very core the dark and obscure stone” (Job 28:3) of a world in despair. Like Job, who cursed the day of his birth, he made his mother’s mouth fill with the anguish of having given birth to a monster: “Ah! why did I not give birth to a whole knot of vipers, / Rather than nourish this mockery” (Bénédiction).

He is the poet of sin, which implies the knowledge of a deeper clarity and the revelation of a wounded love. He was the man of De profundis that cried out in the valley of tears. He regretted that the priest of Honfleur had not understood that his poems were based on “a Catholic idea,” that of the sinner who awaits redemption through death. Baudelaire descended into the underworld, into the opacity of a world that confusedly awaited the light. He is the poet of Holy Saturday. Did he rise again? Did he experience Easter morning? Nadar asked him just before his death: “How can you believe in God?” With “a cry of ecstasy,” he showed the Place de l’Étoile, illuminated by “the splendid pomp of the setting sun.” “He certainly believed,” concluded Nadar.

Little Thérèse was born just after his death, like a little sister. She lived in the heroic faith of a world devoid of hope. She faced the darkness of the ultimate temptation, that of despair. Her manuscripts should be reread as a mysterious response to the “cursed poet”: “I suppose I was born in a country surrounded by a thick fog…. The King of the homeland with the shining sun came to live thirty-three years in the land of darkness. Alas! the darkness did not understand that this Divine King was the light of the world… But Lord, your child… asks you for forgiveness for her brothers. She agrees to eat as long as you want the bread of sorrow and does not want to get up from this table filled with bitterness where poor sinners eat until the day you have marked…”

May she “throw flowers” to the picker of Les Fleurs du mal, who begged Beauty to finally open the door “to an infinite that I love and have never known.”

Father Luc de Bellescize is the Curate of Saint Vincent-de-Paul in Paris. This article comes through the kind courtesy of La Nef.

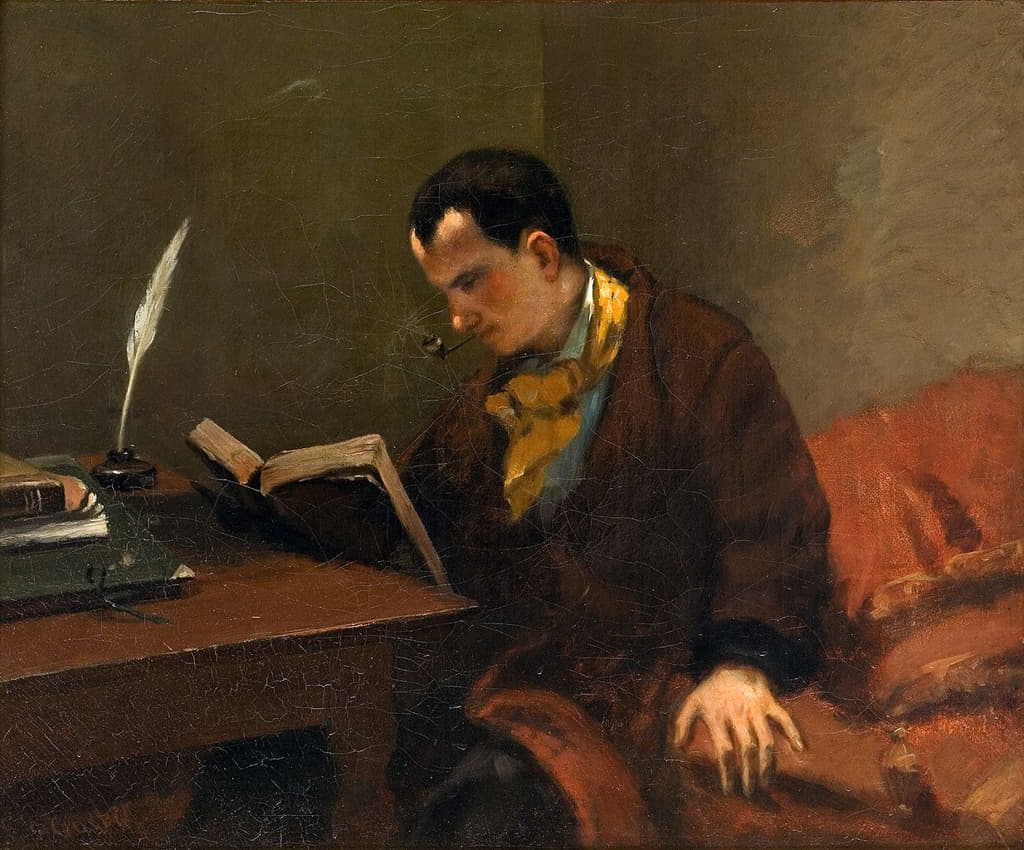

Featured: Portait of Baudelaire, by Gustave Courbet; painted ca. 1848-1849.