With his Théorie de Jésus, recently published by Bouquins, Michel Onfray once again returns to the (in)existence of Christ, and aims to dust off the “mythist” arguments. What does this book offer?

The thesis of the old rationalists is simple, and Onfray’s updating of it is not particularly original in its arguments: since there is “no proof” of the historical existence of Jesus, He can only be a conceptual, “paper” figure. Beyond the usual denials concerning the value of the testimonies of the Gospels and Christian writings (subjective and suspect), the “mini-biography” of Christ given by Flavius-Josephus (a forgery), the mentions of Roman historians (which would prove nothing other than the existence of Christianity), not to mention the material traces (shroud, relics…), Onfray indulges in an astonishing rereading of the life of Jesus.

His “theory”—undoubtedly influenced by a certain fascination with pagan myths—is that the character of Jesus is ultimately no more than a fictional construction, devised to fulfill the expectations and prophecies of the Old Testament. The correspondence between the prophecies and their fulfillment in the life of Christ, piously noted by Christian interpreters and apologists, thus became “proof” of His mythical reality.

The bulk of the book is taken up by an astonishing commentary on the Gospels, oscillating between classical interpretations, highlighting numerous Old Testament parallels, Gnostic flights of fancy and murderous remarks. The author’s Gnostic tropism is apparent in his repeated recourse to apocryphal sources and comparisons with pagan legends, as if Christianity were just another mythology—the only one, however, to have succeeded in establishing itself as real.

The figure of the “Onfrayan Christ” that emerges is not without its paradoxes: a “Judeocidal Jew,” a “nihilist,” who “takes God hostage,” distills a teaching that is sometimes universal, sometimes esoteric, who flouts the commandments of Jewish law and ultimately attracts the deserved wrath of the Jerusalem establishment. On the other hand, any literal reading of the Gospel accounts, especially those relating Jesus’ miracles, is discredited as “rationalism” and “positivism.”

Two hundred and fifty-some pages for a Théorie de Jésus is both a little and a lot, from an author who has already said and written so much on the subject. Reading it, one cannot help but wonder about his own positioning and personal biases. If Jesus is a myth, what is the point of these pages designed to deny His Mother’s virginity, to give this “paper character” blood brothers? If the Gospels are pure fiction, why take the time to question their authenticity and the identity of their authors, and why delay writing them?

Some of the arguments Michel Onfray uses seem decidedly crude and worn. The contradictions and clumsiness of the writing of the New Testament have been the object of pagan mockery since Roman times, but are they a sign of inauthenticity? On the contrary, the overall concordance of the accounts, in the midst of discrepancies in detail, reinforces the idea that the Gospels are indeed eyewitness accounts of real events. The numerous references to the Old Testament do not seem to us to be the hallmark of a legendary narrative, but rather the “touch” of the Jewish authors of the New Testament, deeply rooted in their own culture and references (just as Onfray cannot help quoting Flaubert when he speaks of Jesus). Are Scripture quotations the mark of an artificial character? When Jesus, on the cross, begins Psalm 22 (“My God, my God…”), he is simply using one of the fundamental prayers of His religion, learned from childhood and so often recited, just as a Christian recites his Pater or Ave on his deathbed.

We cannot help but arrive at the end of Théorie de Jésus with a taste of unfinished business. The stumbling block on which its author stumbles is indeed that which, rejected by the builders, became the cornerstone: Christ, God made man, Word incarnate. For the Body of Jesus, His concrete historical reality, refers to our own body and to that incarnate nature which our age rejects. Michel Onfray’s book will hopefully have the merit of raising the question of Christ in the spiritual desert of our time. For us Christians, it contrasts the realization that Christ is a concrete figure, flesh and blood, a real body given and real blood shed out of love to redeem our sins.

Father Paul Roy is a priest of the Fraternity of Saint-Pierre, and moderator of the site and training application Claves. This interview comes through the kind courtesy of La Nef.

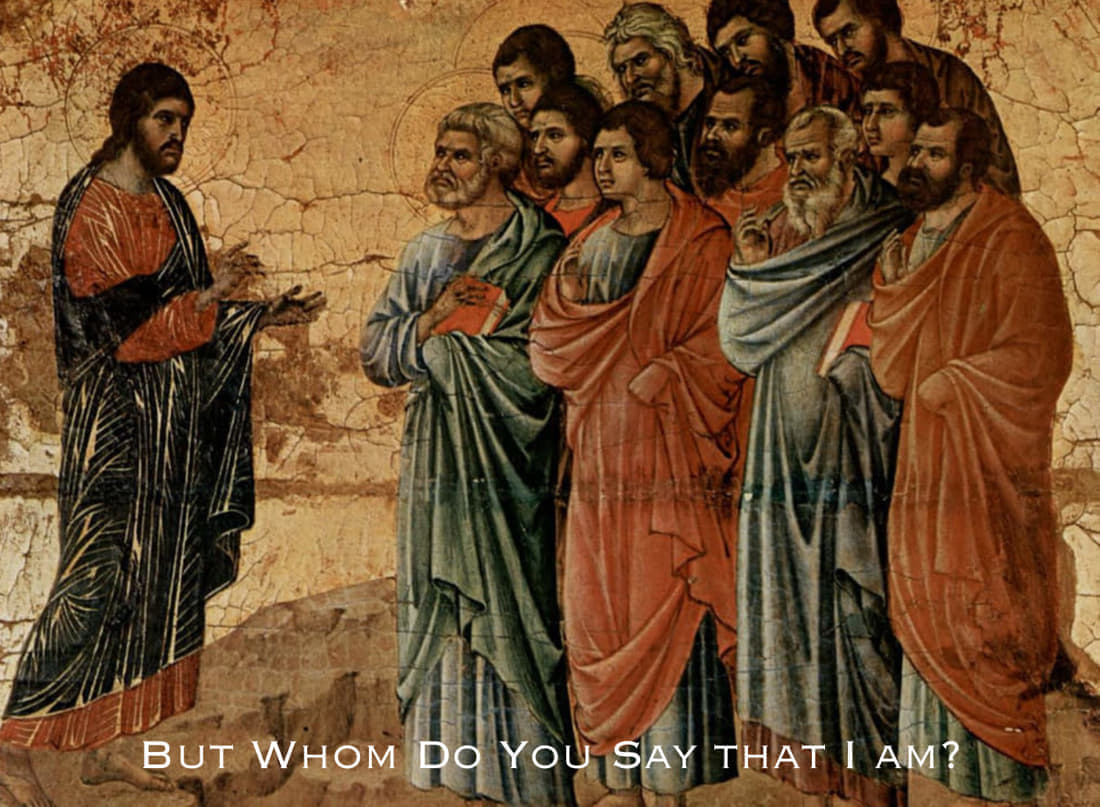

Featured: Christ on the Mount of Galilee, Siena Cathedral, by Duccio di Buoninsegna; painted ca. 1308-1311.