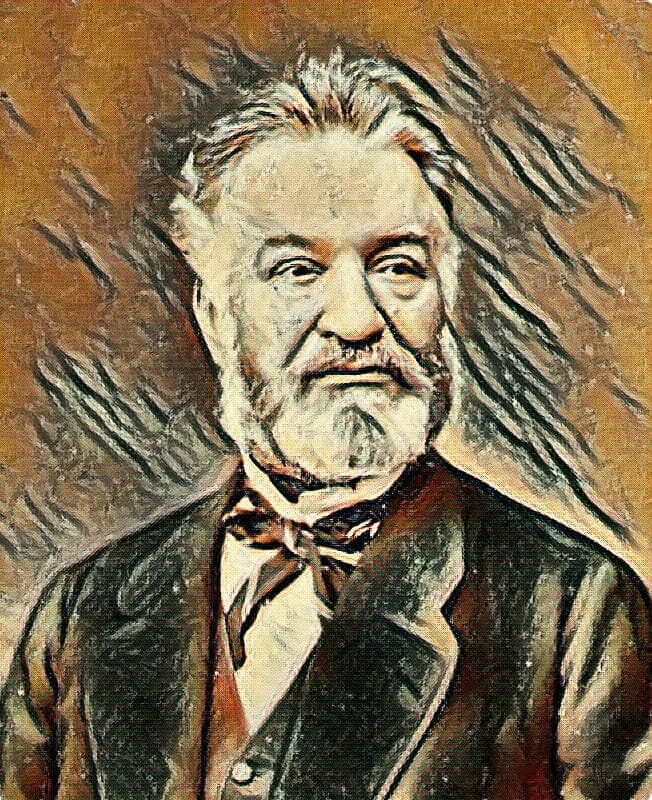

Louis Veuillot (1813-1883), head of L’Univers, exerted a powerful influence on 19th-century French Catholicism. He was also, quite simply, an extraordinary personality. Portrait of a social “ultramontane.”

Rome, 1838. Louis Veuillot, 25, on a mission to the Orient, stopped off in the Italian capital. A journalist for the government press at the time, the young man was disillusioned, having nothing but contempt for the nihilism of his time, whether it had the face of the Voltairean bourgeoisie or revolutionary anarchism. This soul, a friend of religion, yearned for the Absolute, and it was in the Eternal City that he was struck by light: “I was in Rome. At a bend in the road, I met God. He beckoned me, and I hesitated to follow. He took my hand and I was saved.” This “veritable first communion,” which he recounts in Rome et Lorette (Rome and Loretto), was a conversion in the most radical sense of the word. He, the self-taught son of an illiterate cooper living in Bercy, already a bulimic reader and soon an insatiable writer, had just found his way.

A Journalist on Fire

“As soon as he became a Christian, he felt like an apostle,” said his nephew François. Indeed, Louis returned to France animated by a religious zeal that would never leave him, and he chose to dedicate his life to bearing witness to this fire, to making Catholic truth resound everywhere, and also, with the ardor of a convert, to scourging freethinkers of all kinds (including the bourgeois louis-philippard “preceded by his belly and followed by his behind”): “These gentlemen have a great virtue that they preach to us incessantly: tolerance. They tolerate everything, except that we do not tolerate everything they tolerate. And that is where our quarrels come from.”

And it was journalism that was to be the instrument of his apostolate. In 1840, he landed at L’Univers, a moderate Catholic paper with a small readership (1,500 subscribers) and no resources, run by Charles de Montalembert. He soon became its chief editor—along with his brother Eugène, a writer without a genius for the pen but with good business sense—and for forty years made it the leading organ of French Catholicism. Its success was phenomenal: by 1860, the daily had become France’s fifth-largest newspaper, with 13,000 subscribers (and an audience estimated by Mgr Gerbet at 60,000-80,000).

The recipe for such success lies in his popular base. While the bishops always looked on him with a distant, even accusatory eye, the lesser clergy championed this plebeian from the same national bowels. In seminaries, in small parishes and among provincial notables, the flamboyant journalist—whom Thibaudet would say was the greatest of his century—was worshipped. Far from the mundane, he was above all the herald of a faith full of social solicitude, as witness the passage on the death of his father: “On the edge of his grave, I thought of the torments of his life, I recalled them, I saw them all; and I also counted the joys that, despite his servile condition, this heart truly made for God could have tasted. Pure joys, profound joys! The crime of a society that nothing can absolve had deprived him of them! A glimmer of mournful truth made me curse not work, not poverty, not sorrow, but the great social iniquity—impiety—by which the little ones of this world are robbed of the compensation God wanted to attach to the inferiority of their lot. And I felt the anathema burst forth in the vehemence of my pain…”

Veuillot’s journalism continued to be combat journalism, sometimes virulent, driven by a burning concern for the truth, unencumbered by convenience or recognition (he refused the decorations of the Académie française and the Académie des sciences morales): “The journalist forces the stragglers to walk, engages and compromises the timid, holds back the reckless; he binds up the wounded, comforts the vanquished, makes the clumsy understand their false maneuvers and repairs them.” His pen, wielded to wound evil, was genial as it was merciless, as full of ethos as it was of pathos. Hence the polemics and scandals that marked his life.

Church First

Although a staunch monarchist who even drafted a constitution, Louis Veuillot was never a politician—and twice refused to run for parliament. His mantra: “The Catholic Church first, and then what exists; the Catholic Church to improve, correct and transform all things.” His political choices were subordinated to religious interests—a position that heralded the Ralliement. The question is, how to act in a positivist age that has broken with Christianity? Against centrifugal modernity, for fear of dilution, Veuillot opted for centripetal forces: the empire, the Pope, the Church.

However, in the name of the same Catholic interests, the “liberal Catholics” went for the opposite gamble—and this marked the start of a fratricidal war with the “intransigent” Veuillot, who at the same time introduced the writings of the counter-revolutionary Donoso Cortés to France. Born out of the fight for freedom of education, the “Catholic party” fractured over the Falloux Law (which Veuillot disapproved of), then tore itself apart from 1852 onwards. While L’Univers sided with Napoleon III, the “liberals” defended the virtues of parliamentarianism, and considered that the modern regime of freedom (of conscience, expression, the press, association, etc.) allowed and would allow Catholic interests to triumph. The free Church in the free State: “The triumph of the Church in the 19th century will be precisely to vanquish her enemies through freedom, as she vanquished them in the past through the sword of feudalism and the scepter of kings,” professed the sensitive and introverted Montalembert (Les intérêts catholiques au XIXe siècle).

For three decades, infamous adjectives rained down from all sides, and people accused and replied to each other in books. Ozanam, Mgr Dupanloup and de Broglie accused Veuillot of fanaticism. Supported by Mgr Pie, bishop of Poitiers, and reinforced by the encyclicals of Pius IX, the massive plebeian denounced in L’illusion libérale a “rich man’s error which could not have occurred to a man who had lived among the people and who would see the countless difficulties that truth, especially today, experiences in descending and maintaining itself in those depths where it needs all the protection, but particularly the example from above.” In the end, historian Émile Poulat summed up this unfortunate quarrel best: “So-called liberal Catholics are the recurring expression of an unresolved problem in the Church—its place and relationship within our society that has left God behind—while Veuillot remains the witness to an imprescriptible requirement within an anachronistic situation.”

“Lay Legate of the Infallible Pope”

Ironically, L’Univers was banned from publication by the Emperor, between 1860 and 1867, for having published the encyclical Nullis certe verbis, in which the Pope blamed French policy in Italy. A temporary death with apotheosis value. As a reader of Joseph de Maistre, Veuillot was devoted to the papacy—he was very attached to Pius IX—and, along with Dom Guéranger, took up the cause of papal infallibility, a dogma proclaimed at Vatican I (see Veuillot’s Rome pendant le Concile–Rome during the Council). These debates were also an opportunity for him to battle against the “provincial spirit” of the “Gallicans,” whom he accused of threatening the unity of the Church—thereby fueling clear tendencies towards centralization. Together with the apostolic nuncio Fornari, Veuillot was the linchpin of French ultramontanism, the “lay legate of the infallible pope,” as the Journal des Débats put it. On the other hand, the “liberals,” supported by a large part of the French episcopate, feared that infallibility was a cover for political authoritarianism, and, along with Montalembert, denounced the “idol of the Vatican.” The truth surely lay somewhere between these two positions, as Cardinal Newman summed it up in his famous formula: “Conscience has rights because it has duties.” And indeed—a second irony of fate—in 1872, Pius IX reprimanded Veuillot for his vehemence against Dupanloup on the Italian (Roman) question, putting side-by-side “the party which fears the Pope too much” and the “opposite party, which totally forgets the laws of charity.” A rebuke tempered by a benediction that Veuillot would say “enters by breaking the windows!”

A genius of polemic to the point of excess, Louis was not a bad guy. A tender and delicate man, a kind-hearted father of six daughters, he lived and died firmly waving the flag of faith: “In all my life, I have been perfectly happy and proud of only one thing: that is to have had the honor and at least the will to be a Catholic, that is, obedient to the laws of the Church.” All is forgiven.

Rémi Carlu is a French journalist. This article appears courtesy of La Nef.