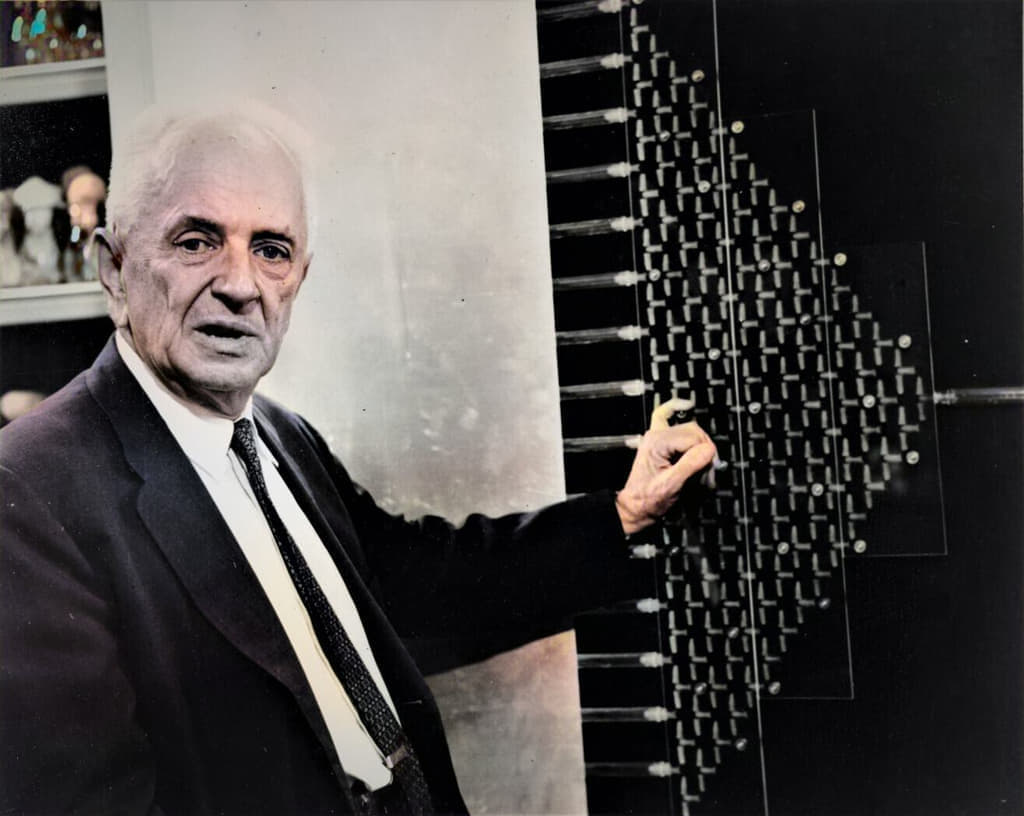

Theodosius Dobzhansky (1900—1975), the greatest Russian-American geneticist and evolutionary biologist of the 20th century. He described a non-fixed universe, in which culture is “the actualization of the potentialities of man as the bearer of spirit.”

What follows is an excerpt from his influential work, The Biology of the Ultimate Concern, in which he examined the role of science within culture which together arrive at an understanding of the “Big Questions,” which in turn establish a “credo” for human life.

Dostoevsky makes his Ivan Karamazov declare: “What is strange, what is marvelous, is not that God really exists, the marvel is that such an idea, the idea of the necessity of God, could have entered the head of such a savage and vicious beast as man; so holy it is, so moving, so wise, and such a great honor it does to man.” This is even more marvelous than Dostoevsky knew. Mankind, Homo sapiens, man the wise, arose from the ancestors who were not men, and were not wise in the sense man can be. Man has ascended to his present estate from one still more savage, not necessarily more vicious, but quite certainly a dumb and irrational one. It is unfortunate that Darwin has entitled one of his two greatest books the “Descent,” rather than the “Ascent,” of man. The idea of the necessity of God, and other thoughts and ideas that do honor to man, were alien to our remote ancestors. They arose and developed, and secured a firm hold on man’s creative thought during mankind’s long and toilsome ascent from animality to humanity.

Organisms other than men have the “wisdom of the body”; man has in addition the wisdom of humanity. Wisdom of the body is the ability of a living system so to react to environmental changes that the probabilities of survival and reproduction are maximized. For example, a certain concentration of salt in the blood is necessary for life; if an excess of salt is ingested, it is eliminated in the urine; if the salt supply is scarce the urine contains little salt. Such “wise” reactions of the body are confined usually to the environments which the species has frequently encountered in its evolutionary development. This built-in “wisdom” arose through the action of natural selection.

The place of the wisdom of humanity in the scheme of things requires a separate consideration. Humanism, according to Tillich (1963), “asserts that the aim of culture is the actualization of the potentialities of man as the bearer of spirit,” and “Wisdom can be distinguished from objectifying knowledge (sapientia from scientia) by its ability to manifest itself beyond the cleavage of subject and object.” This wisdom is the fruit of self-awareness; man can transcend himself, and see himself as an object among other objects. He has attained the status of a person in the existential sense, and with it a poignant experience of freedom, of being able to contrive and to plan actions, and to execute his plans or to leave them in abeyance. Through freedom, he gains a knowledge of good and of evil. This knowledge is a heavy load to carry, a load of which organisms other than man are free. Man’s freedom leads him to ask what Brinton (1953) refers to as Big Questions, which no animals can ask.

Does my life and the lives of other people have any meaning? Does the world into which I am cast without my consent have any meaning? There are no final answers to these Big Questions, and probably there never will be any, if by answers one means precise, objective, provable certitudes. And yet seek for some sort of answers we must, because it is the highest glory of man’s humanity that he is capable of searching for his own meaning and for the meaning of the Cosmos. An urge to devise answers to such “metaphysical” questions is a part of the psychological equipment of the human species. Brinton (1953) rightly says that “Metaphysics is a human drive or appetite, and to ask men to do without metaphysics is as pointless as to ask them to do without sex relations. There are indeed individuals who can practice abstention from metaphysics as there are those who can practice abstention in matters of sex, but they are the exceptions. And as some who repress sex actually divert it into unprofitable channels, so do those who repress metaphysics.

The German word Weltanschauung and the Russian mirovozzrenie have no precise English equivalents. The usual translation, “world view,” subtly betrays the meaning. A world view, like a view from a mountaintop, may be pleasant and even inspiring to behold, but one can live without it. There is a greater urgency about a Weltanschauung, and some sort of mirovozzrenie is felt to be indispensable for a human being. The Latin credo is becoming acclimatized in English in a sense most nearly equivalent to Weltanschauung . It is most closely related to the “ultimate concern” which Tillich considers to be the essence of religion in the broadest and most inclusive sense. “Religion is the aspect of depth in the totality of the human spirit. What does the metaphor depth mean? It means that the religious aspect points to that which is ultimate, infinite, unconditional, in man’s spiritual life. Religion, in the largest and most basic sense of the word, is ultimate concern. And ultimate concern is manifest in all creative functions of the human spirit” (Tillich 1959).

It is the ultimate concern in man that Ivan Karamazov found so strange and so marvelous. Man’s nature impels him to ask the Big Questions. Every individual makes some attempts to answer them at least to his own satisfaction. One of the possible answers may be that the Questions are unanswerable, and only inordinately conceited or foolish people can claim to have discovered unconditionally and permanently valid answers. Every generation must try to arrive at answers which fit its particular experience; within a generation, individuals who have lived through different experiences may, not quite, one hopes, in vain, make sense of those aspects of the world which the individual has observed from his particular situation.

My life has been devoted to working in science, particularly in evolutionary biology. Scientists are not necessarily more, but I hope also not less, qualified to think or to write about the Big Questions than are nonscientists. It is naive to think that a coherent credo can be derived from science alone, or that what one may learn about evolution will unambiguously answer the Big Questions. Some thinkers, e.g., Barzun (1964) dismiss such pretensions with undisguised scorn: “…the scientific profession does not constitute an elite, intellectual or other. The chances are that ‘the scientist,’ from the high-school teacher of science to the head of a research institute, is a person of but average capacity.” And yet even Barzun, no friend or respecter of science, grudgingly admits that science “brings men together in an unexampled way on statements to which they agree without the need of persuasion; for as soon as they understand, they concur.” Some of these “statements” which science produces are at least relevant to the Big Questions, and in groping for tentative answers they ought not be ignored.

The time is not long past when almost everybody thought that the earth was flat, and that diseases were caused by evil spirits. At present quite different views are fairly generally accepted. The earth is a sphere rotating on its axis and around the sun, and diseases are brought about by a variety of parasites and other biological causes. This has influenced people’s attitudes; the cosmology that one credits is not irrelevant to one’s ultimate concern. To Newton and to those who followed him the world was a grand and sublime contrivance, which operates unerringly and in accord with precise and immutable laws. Newton accepted, however, Bishop Ussher’s calculations, which alleges that the world was created in 4004 B.C. The world was, consequently, not very old; it had not changed appreciably since its origin, and it was not expected to change radically in the future, until it ended in the apocalyptic catastrophe. Newton was a student of the Book of Revelation as well as a student of cosmology. In Newton’s world man had neither power enough nor time enough to alter the course of events which were predestined from the beginning of the world.

The vast universe discovered by Copernicus, Kepler, Galileo, and Newton became quite unlike the cozy geocentric world of the ancient and the medieval thinkers. Man and the earth were demoted from being the center of the universe to an utterly insignificant speck of dust lost in the cosmic spaces. The comfortable certainties of the traditional medieval world were thus taken away from man. Long before the modern existentialists made estrangement and anxiety fashionable as the foundations of their philosophies, Pascal expressed more poignantly the loneliness which man began to feel in “The eternal silence of these infinite spaces.” If he worked hard, man could conceivably learn much about how the world was built and operated, but he could not hope to change it, except in petty detail. An individual human was either saved or damned, and those of Calvinist persuasion believed that this alternative was irrevocably settled before a person was even born. This left no place for humanism in Tillich’s sense; an individual man had few potentialities to be actualized, and culture had scarcely any at all.

It has become almost a commonplace that Darwin’s discovery of biological evolution completed the downgrading and estrangement of man begun by Copernicus and Galileo. I can scarcely imagine a judgment more mistaken. Perhaps the central point to be argued […] is that the opposite is true. Evolution is a source of hope for man. To be sure, modern evolutionism has not restored the earth to the position of the center of the universe. However, while the universe is surely not geocentric, it may conceivably be anthropocentric. Man, this mysterious product of the world’s evolution, may also be its protagonist, and eventually its pilot. In any case, the world is not fixed, not finished, and not unchangeable. Everything in it is engaged in evolutionary flow and development.

Human society and culture, mankind itself, the living world, the terrestrial globe, the solar system, and even the “indivisible” atoms arose from ancestral states which were radically different from the present states. Moreover, the changes are not all past history. The world has not only evolved, it is evolving. Now, “In the Renaissance view, the world, a place of beauty and delight, needed not to be changed but only to be embraced; and the world’s people, free of guilt, might be simply and candidly loved” (Durham 1964). Far more often, it has been felt that changes are needed:

“For the created universe waits with eager expectation for God’s sons to be revealed. It was made the victim of frustration, not by its own choice, but because of him who made it so; yet always there was hope, because the universe itself is to be freed from the shackles of mortality and enter upon the liberty and splendor of the children of God. Up to the present, we know, the whole created universe groans in all its parts as if in the pangs of childbirth” (Rom 8:19-22).

Since the world is evolving it may in time become different from what it is. And if so, man may help to channel the changes in a direction which he deems desirable and good. With an optimism characteristic of the age in which he lived, Thomas Jefferson thought that “Although I do not, with some enthusiasts, believe that the human condition will ever advance to such a state of perfection as that there shall no longer be pain or vice in the world, yet I believe it susceptible of much improvement, and most of all, in matters of government and religion; and that the diffusion of knowledge among the people is to be the instrument by which it is to be effected.” This is echoed and reechoed by Karl Marx and by Lenin in their famous maxim that we must strive not merely to know but also to transform the world. In particular, it is not true that human nature does not change; this “nature” is not a status but a process. The potentialities of man’s development are far from exhausted, either biologically or culturally. Man must develop as the bearer of spirit and of ultimate concern. Together with Nietzsche we may say: “Man is something that must be overcome.”

Picasso is alleged to have said that he detests nature. Tolstoy and some lesser lights claimed that any and all findings of science made no difference to them. Fondness and aversion are emotions which admittedly cannot be either forcibly implanted or expurgated. One may detest nature and despise science, but it becomes more and more difficult to ignore them. Science in the modern world is not an entertainment for some devotees. It is on the way to becoming everybody’s business. Some people feel no interest in distant galaxies, in foreign lands, exotic human tribes, and even in those neighbors with whom they are not constrained to deal too often or too closely. Indifference to one’s own person is unlikely. It is feigned by some, but rarely felt deep down, when one is all alone with oneself. This unlikelihood, too, is understandable as a product of the biological evolution of personality in our ancestors. It made the probability of their survival greater than it would have been otherwise. Ingrained in man’s psyche before it was explicitly formulated, the adage “Know thyself” was always a stimulus for human intellect.

To “know thyself,” scientific knowledge alone is palpably insufficient. This was probably the basis of Tolstoy’s scoffing at science. To him science seemed irrelevant to the ultimate concern, and to him only the ultimate concern seemed to matter. But he went too far in his protest. In his day, and far more so in ours, the self-knowledge lacks something very pertinent to the present condition if one chooses to ignore what one can learn about oneself from science. This adds up to something pretty simple, after all: a coherent credo can neither be derived from science nor arrived at without science.

Construction and critical examination of credos fall traditionally in the province of philosophy. Understandably enough, professional philosophers often show little patience with amateurs who intrude into their territory. Scientists turned philosophers fare scarcely better than other amateur intruders. This proprietary attitude is not without warrant, but the matter is not settled quite so easily. What, indeed, is philosophy? Among the numerous definitions, that given by Bertrand Russell (1945) is interesting: “between theology and science there is a No Man’s Land, exposed to attacks from both sides; this No Man’s Land is philosophy.” Less colorfully, philosophy is defined as the “science of the whole,” which critically examines the assumptions and the findings of all other sciences, and considers them in their interrelations. Still other definitions claim that philosophy works to construct a coherent Weltanschauung . Under any of these definitions, scientists may have some role to play, at least on the outskirts of philosophy. At the very least, they must be counted among the purveyors of raw materials with which philosophers operate when they formulate and try to solve their problems. With some notable exceptions, modern schools of philosophy, especially in the United States and England, have been taking their cues very largely from the physical sciences; the influential school of analytical philosophy is engrossed with mathematics and linguistics. Biology and anthropology are neglected. Of late, there appear to be, however, some straws in the wind portending change.

The relevance of biology and anthropology is evident enough. In his pride, man hopes to become a demigod. But he still is, and probably will remain, in goodly part a biological species. His past, all his antecedents, are biological. To understand himself he must know whence he came and what guided him on his way. To plan his future, both as an individual and much more so as a species, he must know his potentialities and his limitations. These problems are only partly biological and scientific, and partly “theological.” In short, they are philosophical problems in Bertrand Russell’s sense.

Since I am a biologist without formal philosophical and anthropological training, the task which I set for myself is quite likely overambitious. I wish to examine some philosophical implications of certain biological and anthropological findings and theories. This small book [The Biology of the Ultimate Concern, 1967] lays no claim to being a treatise either on philosophical biology or on biological philosophy. It consists of essays on those particular aspects of science which have been particularly influential in the formation of my personal credo. This is said not in order to disarm the potential critics of these essays, but only to explain what may otherwise appear a rather haphazard selection of topics discussed and of those omitted in the pages that follow. Together with Birch (1965) I submit that:

My scientific colleagues might well say, “Cobbler, stick to your last.” But we have been doing that in science for long enough. I have attempted what is not a very popular endeavour in our generation. It is to cover a canvas so broad that the whole cannot possibly be the specialized knowledge of any single person. The attempt may be presumptuous. I have made it because of the urgency that we try, in spite of the vastness of the subject. I would not have written had I not discovered something for myself that makes sense of the world of specialized knowledge in which I live.

Featured: Theodosius Dobzhansky demonstrates the Hirsch index, 1966.