The Question of Man

In our time, it is becoming increasingly clear that it is man himself who is in question. And at the same time, it is becoming increasingly clear that we are living at a critical, extremely critical moment in history—and it is possible (and even likely to be so) that we are living in the end times.

Epidemics and wars are mowing down millions of human lives. In the Special Military Operation (SMO) the world is brought to the brink of a nuclear war, which, if started, could end humanity’s existence.

At the same time, the horizons of the post-human future are becoming clearer in philosophy and science. The Singularity theory, the transfer of the initiative to a strong Artificial Intelligence, the success of genetic engineering, the improvement of robotics, attempts to merge people and machines (creation of cyborgs)—all this calls into question the very species of man, proposing to turn this page of history and decisively enter the era of posthumanism, transhumanism.

In such a situation, it is extremely important to address the anthropological issue anew with the utmost seriousness. If man is on the verge of extinction, annihilation, fundamental and irreversible mutation, then what is he after all? What was he? What is his essence and his mission? By approaching the limit, man can better review his own forms, and thus grasp his eidos, his essence.

Such a review can be done in many different ways. It all depends here on the original point of view. Each scientific or ideological paradigm will proceed from its own structures. In this paper we aim to make sense of man primarily in the context of Christian eschatology. But in order to clarify how Christian doctrine represents man, his nature and his destiny in the last times, it is necessary first to make an excursion into a more general problematic of religious anthropology in general.

Humanity’s Dualism at the Last Judgment

The end of the world in the Christian tradition (as well as in other versions of monotheism) is described in some detail. The culmination of all world history will be the moment of the Last Judgment. And here we encounter the main feature of eschatological anthropology: dualism, the final division of humanity into two groups, represented by the images of lambs (cattle, flock—πρόβατον) and goats (ἔριφος). The lambs are the elect who receive a good answer at the Last Judgment. The goats are the damned, doomed to eternal destruction. The lambs go to the right, to salvation; the goats go to the left, to damnation.

Matthew’s Gospel describes this division this way (Mt 25:31-36):

31 When the Son of Man comes in his glory, and all the angels with him, then he will sit on the throne of his glory.

31 Ὅταν δὲ ἔλθῃ ὁ υἱὸς τοῦ ἀνθρώπου ἐν τῇ δόξῃ αὐτοῦ καὶ πάντες [a]οἱ ἄγγελοι μετ’ αὐτοῦ, τότε καθίσει ἐπὶ θρόνου δόξης αὐτοῦ·

32 All the nations will be gathered before him, and he will separate people one from another as a shepherd separates the sheep from the goats,

32 καὶ συναχθήσονται ἔμπροσθεν αὐτοῦ πάντα τὰ ἔθνη, καὶ ἀφορίσει αὐτοὺς ἀπ’ ἀλλήλων, ὥσπερ ὁ ποιμὴν ἀφορίζει τὰ πρόβατα ἀπὸ τῶν ἐρίφων,

33 and he will put the sheep at his right hand and the goats at the left.

33 καὶ στήσει τὰ μὲν πρόβατα ἐκ δεξιῶν αὐτοῦ τὰ δὲ ἐρίφια ἐξ εὐωνύμων.

34 Then the king will say to those at his right hand, “Come, you that are blessed by my Father, inherit the kingdom prepared for you from the foundation of the world;

34 τότε ἐρεῖ ὁ βασιλεὺς τοῖς ἐκ δεξιῶν αὐτοῦ· Δεῦτε, οἱ εὐλογημένοι τοῦ πατρός μου, κληρονομήσατε τὴν ἡτοιμασμένην ὑμῖν βασιλείαν ἀπὸ καταβολῆς κόσμου.

35 for I was hungry and you gave me food, I was thirsty and you gave me something to drink, I was a stranger and you welcomed me,

35 ἐπείνασα γὰρ καὶ ἐδώκατέ μοι φαγεῖν, ἐδίψησα καὶ ἐποτίσατέ με, ξένος ἤμην καὶ συνηγάγετέ με,

36 I was naked and you gave me clothing, I was sick and you took care of me, I was in prison and you visited me.”

36 γυμνὸς καὶ περιεβάλετέ με, ἠσθένησα καὶ ἐπεσκέψασθέ με, ἐν φυλακῇ ἤμην καὶ ἤλθατε πρός με.

This formulation suggests that the division occurs among the nations (πάντα τὰ ἔθνη), but tradition interprets it as a division among people on a deeper—ontological—principle. Sheep are those whose nature turns out to be good. The goats—and here a clear reference to the ancient Hebrew rite of casting out the scapegoat—are those who have moved decisively to the side of evil.

Eschatology thus sees the end of human history not as a unity, not ex pluribus unum facere (from many one), but precisely as a division, a division, a fundamental fork.

Humanity at the Last Judgment is bifurcated, and finally and irreversibly. The result of humanity’s existence in time is its distribution into two sets, which in this very bifurcated state enters eternity. It is no longer a stage, not an intermediate position, but precisely an irreversible end. The end of man is the absolute and irrevocable decision of God at the Last Judgment.

Thus, eschatology strictly states that the omega point for humanity will be its bifurcation, the division into sheep and goats. On the damned—as scapegoats—will be symbolically placed all the sins of humanity, and as such they will be separated from the rest, whose sins will, by contrast, be forgiven by divine Grace.

The Particular Unity of the Church

So, the end of man will be his bifurcation. Biblical tradition begins human history with Adam and Paradise. Man was created as one, and his division into man and woman (Eve’s creation) was the prelude to the fall into sin and further fragmentation. The end result of the entire historical process will be the Last Judgment. We can say that the general vector of history moves from unity to duality.

In this, Christian teaching is based on the fact that in the final stages of sacred history, the process of fall into sin was overcome by the voluntary sacrifice of the Son of God, Jesus Christ, who restored—but on another ontological level—the original unity, uniting scattered people into a new wholeness—the Church of Christ. The unity of the Church restores the unity of Adam and forms the part of humanity which at the Last Judgment will be numbered among the sheep, the flock of Christ. But this unity is not mechanical. It is not the result of adding up everyone. Only the saved are included in the unity and wholeness (synodality) of the Church as emphasized in the Creed (“I believe… in the one holy and apostolic Church”). This is what the Gospel parable about those invited to the wedding feast tells us— ” For many are called, but few are chosen (Mt. 22:14).” After all, the unity of the Church consists of the fellowship of the elect—the saints, the saved, those who have accepted Christ, and those who have remained faithful to this choice until their last breath. Sinners, on the other hand, do not inherit the Kingdom of God; they are cast out of it. They have no part in the “next age.” Their fate is utter destruction, the disappearance into the abyss. Therefore, the unity of the Church does not include those who have voluntarily renounced it.

Unity by Subtraction

This theme of the unity of the Church, which does not include sinners, is saturated with a fundamental metaphysical meaning. Unity is usually understood as an addition, that is, the addition of all the parts, which is intended to recreate some whole. This is partly the meaning of “synodality,” that is, “gathering together.” By putting everything together, we would have unity. But in the case of the anthropology of the Last Judgment, this is not quite so, or even not at all.

The unity of the Church includes the saints, the righteous, and the saved. But—it excludes sinners, or rather absolute sinners—unrepentant and unredeemed by loved ones and saints.

This problem came to a head in connection with Origen’s doctrine of Apocatastasis, that is, the strictly Platonic understanding that the unity (split at the beginning of the manifestation of the world) process will be fully restored at the end of time, including repentance of the fallen angels, and even the devil himself, thus forgiving them. Here, indeed, unity is thought of as first the scattering and then the gathering together of all that is scattered, including sinners and Lucifer.

But this doctrine was rejected by the Church. And this is clearly no accident; rather, a completely different understanding of unity is emphasized. Unity includes the saved and excludes the damned. Unity is subtraction, not addition. Those who go the way of the goats take on the negative side of creation. What is, is affirmed as such, but it involves a kind of purification from what is not. And men and angels who have taken the path of evil take it upon themselves to become bearers of non-existence.

Theology is based on a radical gap between the two natures—the nature of God and the nature of the world He created. Their separation becomes explicit at the moment of the beginning of creation, and is subject to judgment at the moment of its end. That is, metaphysically there is 1 and 1, one God and one creation (as not God). To affirm the oneness of each unit, one must deny the existence of the other. God is so superior to creation that there is, even when there is no creation. Thus, this oneness of God equates the world with nothingness. Hence creation ex nihilo.

But there is also a satanic unity of the world opposed to God. For the world to be one and the same, there must be no God. This is what the devil is going for—and also the entire depiction of the world of the European New Age. The unity of the world is ensured by the nonexistence of God.

In both cases, unity is the result of the negation of the second unity, that is, subtraction. One of the units of the formula 1+1 must be subtracted, taken with a minus sign. To get unity from 2 you must subtract 1. One must gather that which belongs to the unit of God and deny that which belongs to the unit of the devil. Or vice versa.

Hence the main problem of eschatological anthropology. At the Last Judgment, the cursed part of humanity is subtracted from humanity, becoming a collective—cathedral!—”scapegoat.” And it is this condemnation of sinners that constitutes the fullness of the assembly of the righteous. All humanity is humanity minus those who have sided with Satan. And it is the act of subtracting that makes this humanity complete.

In the act of creating something that would not be God in nature, there must be involved both something of God and something not of God, that is, nothing. Something of God mixes with something that is not of God—like soul with body, spirit with dust. And this mixing is not unity. It is only a task given to the subject. In choosing spirit, the subject chooses the Church, unity with God, in His direction. By choosing the opposite, that is, dust, matter, materialism, the subject chooses nothing. The righteous man purifies spirit from matter; the sinner purifies matter from spirit. By subtracting each other from humanity, the two parts build the ontological foundation of eschatological anthropology. The unity of the righteous represents the synodality of being, which surrenders itself to God, the true One and Only. The aggregation of sinners forms the army of the damned, the cathedral of nothingness. A collective of scapegoats.

The Scapegoat

We should look more closely at the Gospel image of the separation of sheep and goats. There is clearly a distinct reference to the Old Testament sacrificial rite in which one goat was separated from the sacrificial animals (sheep and bulls), which became the “scapegoat” (Hebrew for “azazel”— עֲזָאזֵֽל—the expression לַעֲזָאזֵֽל—literally, “for complete removal”). In the Septuagint this expression was translated as ἀποποπομπαῖος τράγος, Latin caper emissarius.

The book of Leviticus gives this description of Aaron’s sacrifice (Lv. 16:21-22):

21 and Aaron shall lay both his hands upon the head of the live goat, and confess over him all the iniquities of the people of Israel, and all their transgressions, all their sins; and he shall put them upon the head of the goat, and send him away into the wilderness by the hand of a man who is in readiness.

21 καὶ ἐπιθήσει ᾿Ααρὼν τὰς χεῖρας αὐτοῦ ἐπὶ τὴν κεφαλὴν τοῦ χιμάρου τοῦ ζῶντος καὶ ἐξαγορεύσει ἐπ᾿ αὐτοῦ πάσας τὰς ἀνομίας τῶν υἱῶν ᾿Ισραὴλ καὶ πάσας τὰς ἀδικίας αὐτῶν καὶ πάσας τὰς ἁμαρτίας αὐτῶν καὶ ἐπιθήσει αὐτὰς ἐπὶ τὴν κεφαλὴν τοῦ χιμάρου τοῦ ζῶντος καὶ ἐξαποστελεῖ ἐν χειρὶ ἀνθρώπου ἑτοίμου εἰς τὴν ἔρημον,

כא וְסָמַךְ אַהֲרֹן אֶת-שְׁתֵּי יָדָו, עַל רֹאשׁ הַשָּׂעִיר הַחַי, וְהִתְוַדָּה עָלָיו אֶת-כָּל-עֲוֺנֹת בְּנֵי יִשְׂרָאֵל, וְאֶת-כָּל-פִּשְׁעֵיהֶם לְכָל-חַטֹּאתָם; וְנָתַן אֹתָם עַל-רֹאשׁ הַשָּׂעִיר, וְשִׁלַּח בְּיַד-אִישׁ עִתִּי הַמִּדְבָּרָה.

22 The goat shall bear all their iniquities upon him to a solitary land; and he shall let the goat go in the wilderness.

22 καὶ λήψεται ὁ χίμαρος ἐφ᾿ ἑαυτῷ τὰς ἀδικίας αὐτῶν εἰς γῆν ἄβατον, καὶ ἐξαποστελεῖ τὸν χίμαρον εἰς τὴν ἔρημον.

כב וְנָשָׂא הַשָּׂעִיר עָלָיו אֶת-כָּל-עֲוֺנֹתָם, אֶל-אֶרֶץ גְּזֵרָה; וְשִׁלַּח אֶת-הַשָּׂעִיר, בַּמִּדְבָּר.

On other occasions, the “scapegoat” was thrown off a cliff. This ritual clearly resonates with the Gospel account of how Jesus Christ healed a demoniac in the country of Gadara, commanding the demons to come out of him and inhabit a herd of pigs grazing nearby. The demons obeyed, and the entire herd rushed to the precipice and tumbled from it into the abyss. In this case, the role of the “scapegoat” is played by the herd of pigs, which took upon themselves the sins for which the demon-possessed suffered.

According to tradition, a piece of red woolen cloth was tied to the goat to be sent off to the desert. Part of it the Old Testament priest tore off during the passage of the goat through the city gates and hung it in public view. If God accepted the cleansing sacrifice, the cloth would miraculously turn from red to white.

It is important to note that the scapegoat was separated specifically from the sacrificial animals, which were considered clean, and it represented a special sacrifice. The complex symbolism of the scapegoat, associated it with the fallen angel, Satan, but remained entirely within the structure of Jewish monotheism. In the apocryphal book of Enoch (8:1), Azazel appears as the name of one of the “fallen angels.”

In ancient Greece, a similar ritual was associated with the ritual execution of a criminal who took the sins of the community (φαρμακός, κάθαρμα, περίψημα). In this, we can likely recognize echoes of the ancient cults of Dionysus. [The French philosopher René Girard based his philosophical system on an analysis of the scapegoat figure, in his books, The Scapegoat, Violence and the Sacred, I See Satan Falling Like Lightning].

It should be emphasized here that the final fate of humanity at the Last Judgment divides it into a sacrifice pleasing to God (the sheep, and not by chance the lamb symbolizes Christ himself) and those who are sent away, separated, cut off, fall away from the main flock (humanity). The goats are not pleasing to God, are not accepted by Him, and therefore are rejected—perishing without a trace in the wilderness or falling into the abyss.

Here we may recall the story of the two children of Adam (the unity of mankind), Abel and Cain. Abel’s sacrifice is accepted and Cain’s is rejected. The creation of Eve (the division of man), which led to the eating of the forbidden fruit from the tree of the knowledge of good and evil (again the duality opposite to the unity of the tree of life) and the birth of the two brothers Cain and Abel (the story of the first murder) are all initial prototypes of the final human story, the last sacrifice at the Last Judgement.

Thus, at the end of the world, humanity’s duality, manifested in its irreversible division, becomes fully explicit, obvious, but implicitly this division began already in paradise.

The Division of Angels

However, even before the creation of man, a similar division occurs at the level of the angels. Created immortal, incorporeal and eternal spirits, angels are divided into two halves (Ps. 90/91:7):

A thousand shall fall at thy side, and ten thousand at thy right hand: but it shall not come nigh thee

πεσεῖται ἐκ τοῦ κλίτους σου χιλιὰς καὶ μυριὰς ἐκ δεξιῶν σου πρὸς σὲ δὲ οὐκ ἐγγιεῖ

יִפֹּל מִצִּדְּךָ ׀ אֶלֶף וּרְבָבָה מִימִינֶךָ אֵלֶיךָ לֹא יִגָּשׁ׃

Here, too, the original unified angelic nature is dissected. Part of the angels are faithful to God and retain their supreme position in creation. The second part, under Danica (Hebrew בֶּן-שָׁחַר “son of the dawn,” Greek ἐωσφόρος, Latin Lucifer) or Satan (Hebrew שָׂטָן—literally, “adversary,” “enemy”) rebels against God and His creation, and as a result of the battle of angels, in which the good angels are victorious, he falls to the very bottom of existence—the realms below the bottom of creation.

Thus, the history of man and his separation echoes the fate of the higher incorporeal entities, the angels, who are also divided into two irreconcilable halves. In a sense, this is the logical result of the freedom that God has fully given to His creation. Every being endowed with intelligence and will, whether human or angel, is capable of consciously making a fundamental choice—to be with God or without Him, and without Him, in the end, means against Him; that is, the way of rebellion and godlessness. Such a choice inevitably leads to the abyss and turns the subject’s being into a rejected victim, that is, a scapegoat.

According to the teaching of the Church, the Last Judgment will determine the final fate not only of human beings, but also of angels. [And the angels who kept not their principality, but forsook their own habitation, he hath reserved under darkness in everlasting chains, unto the judgment of the great day (The Epistle of the Holy Apostle Jude 1:6)]. It is then that Jesus Christ, along with the good angels and saints, will also condemn the evil angels, who shall share the fate of the goats, the “scapegoats,” and finally perish in the abyss.

Thus, eschatological anthropology is inextricably linked to angelology. People and angels have a similar fate—both are given the fullness of mind and will and, therefore, the ontological fullness of freedom. And with the support of this freedom, both determine their own destiny—to become God’s accepted sacrifice or rejected. From indefinite unity, the path of the intelligent creature leads to the ultimate and irreversible bifurcation of the Last Judgment.

The Common Destiny of Men and Angels

The commonality of the destinies of humans and angels is an essential element of religious anthropology. Both begin in unity and end in separation. Both are fully endowed with freedom, intelligence, and will. But they belong to two different dimensions—humans are endowed with a dense body, which angels are not, and are therefore mortal (in body). Angels do not have bodies and do not depend on a dense shell—they maintain their existence from the beginning to the end of creation. Therefore, their choice is not in time, but in eternity—Danica fell in the very origins of time, and falls on the continuation of the entire history of the world and will finally be overthrown at the Last Judgment. Angels have a different scale, but the same ontological problematics as humans.

This scale, in addition to temporality, is also reflected in the fact that the angels, being free from the body, are able to control the bodily elements of the world. Hence their power. The Apocalypse gives a picture of the end times, when angels, faithful to God, inflict world plagues on mankind. And Satan, the fallen angel, is called by the apostles “the prince of this world” (Jn 12:31) and even “the god of this age” (2Cor 4:4), which emphasizes the enormous scope of his power in controlling the processes of the cosmos.

It can be said that the history of man goes from the unity of Adam to the final separation at the Last Judgment in the horizontal—temporal—dimension. The “history” of the angels is vertical. It is organized along the axis of eternity, which permeates creation once and for all. That is why the devil appears already in paradise, and in the end times he takes almost complete power over the world. And they have a common end—the Last Judgment. At the beginning and end of world history, the fate of angels is extremely close to the fate of people, and the eternal vertical of creation with the horizontal of time. And this leads us to be more attentive to both dimensions, the anthropological and the angelological, which can never be completely separated from each other. At the beginning and end of history, the respective moments—unity and bifurcation—unite angels and humans fully. But even in the intervening epochs—as well as in the different slices of the angelic vertical—humans and angels are in close proximity to one another.

Most importantly, human history and the destiny of angels are defined by a fundamental code of bifurcation. In eschatology this becomes fully explicit. It is at the end of time at the Last Judgment that the whole truth about the fall of the angels will be revealed. Similarly, the entire content of man’s being in time will also be revealed—the secret will be revealed [Mt 10:26; Mk 4:22; Lk 17).

The commonality of humans and angels is structured by a fundamental duality: Humans, occupying the middle—horizontal—layer of creation, move to the final separation gradually—in the course of the historical process, reaching its culmination at the moment of the Last Judgement (here human duality is manifested in absolute degree). The fall of angels takes place vertically and instantaneously—in the context of a created eternity, always simultaneous for any moment of historical time. This is why the dualism of angels is permanent. It is always there, from the beginning of time to its end; but the final condemnation of fallen angels will coincide with the Last Judgment.

In other words, the dualism of humanity is implicit in the course of history, while the dualism of angels is explicit in relation to any moment of human history—the choice of people unfolds in time, the choice of angels is instantaneous. At the same time, the dualization of humanity unfolds in the context of the once and for all accomplished fall of the angels. Both dimensions create the volume of the ontological process, which, in fact, is sacred history.

The Anthropology of the Psalms (Avdeyenko ‘s Interpretation)

This fundamental dualism of anthropology (as well as angelology) is brought to sharp focus by the contemporary Russian Bible scholar, philosopher, and theologian Yevgeny Avdeyenko. In his interpretation of the Psalms and the Book of Job, he gives a detailed interpretation of the entire ontological scope of human duality, interpreting the biblical texts in this way. Avdeyenko emphasizes that the Psalter plays such an exceptional role in Christian tradition and liturgy precisely because it presents the fundamental structure of man, and King David appears as the most vivid example of man as such—summarizing the ontological history of Adam and anticipating the new Adam of Christ. The entire content of the Psalms is a narrative of the structure, nature and destiny of man as such. And this is precisely its enduring significance.

Avdeyenko’s contrasting emphasis on the anthropological nature of the Psalms is accompanied by another crucial point: in his reading, the Psalter opens as a fundamentally dualistic narrative where the main content is the opposition between two zones of existence—light and darkness, good and evil, the heavenly realm and the underground hell (Sheol)—right down to its lowest layer, the abyss of Abaddon. God is one, but precisely because He is one and only He is one, being is essentially dual. This will be fully revealed in the division of the Last Judgment, but for Avdeenko this same dualism predetermines the entire content of anthropology and sacred history, of which the Psalter is the semantic mediator.

Anthropological (as well as angelological) dualism for Avdeyenko is not postponed until the final chord of the end times; it operates initially and without interruption and is the main key to comprehending religion as such. Here it is appropriate to recall what we said about the vertical along which the fall of the angels has forever passed, is passing and will continue to pass. Man—Adam, David—is always placed in the middle of this vertical, where the choice is possible in time. The finalization of this choice will coincide with the end of time. But the impact of the two opposing poles man always feels—in every moment of his existence. He always faces the choice of Cain and Abel, the faithful Apostles or Judas, the archangel Michael or Danica. In contrast to the angels, whose choice has always been made and made unambiguously, man has until his last breath the possibility of changing his ontological camp—” Turn away from evil and do good: seek after peace and pursue it” (Ps 33:15). And then he has only to wait for the Last Judgment.

Man’s dualism includes time. This is the core of his moral nature. Man is never mechanically doomed to be good or evil. It is a choice made throughout a person’s life. This is what the Psalms tell us, as Avdehyenko discusses at length.

Children of Light and Children of Darkness

Anthropological dualism is already found in a purely Christian context in the Apostle Paul. In his First Letter to the Thessalonians, he writes:

5 For all you are the children of light, and children of the day: we are not of the night, nor of darkness.

5 πάντες γὰρ ὑμεῖς υἱοὶ φωτός ἐστε καὶ υἱοὶ ἡμέρας. οὐκ ἐσμὲν νυκτὸς οὐδὲ σκότους·

6 Therefore, let us not sleep, as others do; but let us watch, and be sober.

6 ἄρα οὖν μὴ καθεύδωμεν [b]ὡς οἱ λοιποί, ἀλλὰ γρηγορῶμεν καὶ νήφωμεν.

7 For they that sleep, sleep in the night; and they that are drunk, are drunk in the night.

7 οἱ γὰρ καθεύδοντες νυκτὸς καθεύδουσιν, καὶ οἱ μεθυσκόμενοι νυκτὸς μεθύουσιν·

8 But let us, who are of the day, be sober, having on the breastplate of faith and charity, and for a helmet the hope of salvation.

8 ἡμεῖς δὲ ἡμέρας ὄντες νήφωμεν, ἐνδυσάμενοι θώρακα πίστεως καὶ ἀγάπης καὶ περικεφαλαίαν ἐλπίδα σωτηρίας·

In John’s Gospel, Jesus himself speaks of the “children of light” (John 12:36):

36 Whilst you have the light, believe in the light, that you may be the children of light. These things Jesus spoke; and he went away, and hid himself from them.

36 ὡς τὸ φῶς ἔχετε, πιστεύετε εἰς τὸ φῶς, ἵνα υἱοὶ φωτὸς γένησθε. Ταῦτα ἐλάλησεν Ἰησοῦς, καὶ ἀπελθὼν ἐκρύβη ἀπ’ αὐτῶν.

Paul’s division into “sons of light” (υἱοὶ φωτός) and “sons of darkness” (υἱοὶ σκότους) draws our attention to the same anthropological dualism. Those who are with God, with Christ, those who believe in light are the humanity of Abel, Noah, the forefathers, the saints, and the martyrs. They, being in time, prepare with their being the sacrificial animals of the Last Judgment—the sheep, the lambs. This is the humanity of light. But people do not become such by predestination, by birth, or by rigid mechanical conditions, but by their own free will. Only those who are absolutely free can choose between light and darkness. And this is why Paul calls Christians precisely to “become” sons of light, to become them—to be awake, to stay awake, to awaken from the inertia of everyday life. To be “sons of light” means to become “sons of light,” to put ourselves into “sons of light. Jesus Christ himself says the same thing in John’s Gospel—”Believe in the light, that you may be sons of light.” If you believe, you will become sons. No one is born a son of light knowingly. Man always, personally, determines his own nature—placing it either above himself—in the realm of the faithful angels, or below himself—giving himself to the attraction of Danica, sinking into Sheol, slipping into the abyss of Abaddon. And if a man falls, turning away from the light, he becomes a “son of darkness,” a “son of night.” Again, he is not born, but he becomes—constituting his being himself with the support of freedom—mind and will. No one can be forced to become a “son of light” or a “son of darkness.” There is always a choice. Man is this choice himself. This, in fact, is what the Psalms and the Gospels tell us, and what the Bible as a whole tells us.

Anthropology and the Physics of the Resurrection

The Last Judgment occurs after the resurrection of the dead. Christian teaching specifies that “not all will die, but all will be changed.” The apostle Paul writes (I Cor 15:51-52):

51 Behold, I tell you a mystery. We shall all indeed rise again: but we shall not all be changed.

51 ἰδοὺ μυστήριον ὑμῖν λέγω· [a]πάντες οὐ κοιμηθησόμεθα πάντες δὲ ἀλλαγησόμεθα,

52 In a moment, in the twinkling of an eye, at the last trumpet: for the trumpet shall sound, and the dead shall rise again incorruptible: and we shall be changed.

52 ἐν ἀτόμῳ, ἐν ῥιπῇ ὀφθαλμοῦ, ἐν τῇ ἐσχάτῃ σάλπιγγι· σαλπίσει γάρ, καὶ οἱ νεκροὶ ἐγερθήσονται ἄφθαρτοι, καὶ ἡμεῖς ἀλλαγησόμεθα.

The dualism of eschatological anthropology will be fully revealed, after this fundamental metamorphosis of humanity, when the resurrected dead will coexist with the changed—clothed in incorruptible flesh—of the living.

To better understand the meaning of the resurrection of the dead, the expectation of which is included in the “Creed” of the Christian, and therefore is an integral part of all doctrine, we should turn to the phases of creation. The eschatological processes partly repeat the phases of creation in reverse order. Creation comes from God and is directed outward (toward Him). The end of time brings creation back to God, puts it in the face of God—bringing it to His judgment. This return is the universal resurrection, where the entire content of the history of the world is recreated instantly and simultaneously.

But resurrected humanity requires different ontological conditions compared to the world in which we find ourselves. These conditions can be summarized as the physics of resurrection. Other laws are in effect here—beyond the usual time and space. The apostle Paul says this about the physics of the resurrection (I Cor 15:39-44):

39 All flesh is not the same flesh: but one is the flesh of men, another of beasts, another of birds, another of fishes.

39 οὐ πᾶσα σὰρξ ἡ αὐτὴ σάρξ, ἀλλὰ ἄλλη μὲν ἀνθρώπων, ἄλλη δὲ σὰρξ κτηνῶν, ἄλλη δὲ [a]σὰρξ πτηνῶν, ἄλλη δὲ ἰχθύων.

40 And there are bodies celestial, and bodies terrestrial: but, one is the glory of the celestial, and another of the terrestrial.

40 καὶ σώματα ἐπουράνια, καὶ σώματα ἐπίγεια· ἀλλὰ ἑτέρα μὲν ἡ τῶν ἐπουρανίων δόξα, ἑτέρα δὲ ἡ τῶν ἐπιγείων.

41 One is the glory of the sun, another the glory of the moon, and another the glory of the stars. For star differeth from star in glory.

41 ἄλλη δόξα ἡλίου, καὶ ἄλλη δόξα σελήνης, καὶ ἄλλη δόξα ἀστέρων, ἀστὴρ γὰρ ἀστέρος διαφέρει ἐν δόξῃ.

42 So also is the resurrection of the dead. It is sown in corruption, it shall rise in incorruption.

42 Οὕτως καὶ ἡ ἀνάστασις τῶν νεκρῶν. σπείρεται ἐν φθορᾷ, ἐγείρεται ἐν ἀφθαρσίᾳ·

43 It is sown in dishonour, it shall rise in glory. It is sown in weakness, it shall rise in power.

43 σπείρεται ἐν ἀτιμίᾳ, ἐγείρεται ἐν δόξῃ· σπείρεται ἐν ἀσθενείᾳ, ἐγείρεται ἐν δυνάμει·

44 It is sown a natural body, it shall rise a spiritual body. If there be a natural body, there is also a spiritual body.

44 σπείρεται σῶμα ψυχικόν, ἐγείρεται σῶμα πνευματικόν. Εἰ ἔστιν σῶμα ψυχικόν, [d]ἔστιν καὶ πνευματικόν.

These are the properties of the resurrected body—it is

- incorruptible,

- in glory,

- in power,

- spiritual.

So also the Second Coming of Christ takes place in power and in glory. Hence the expression Savior-in-Power (Majesta Domini, Pantocrator), referring to the figure of Jesus Christ, the Almighty, seated on the Throne in Heaven. Here incorruption and the spiritual nature of the world are revealed directly as an area of direct experience. The moment of the Last Judgment reveals a special ontological dimension.

Eternal Creation

The physics of resurrection will become clearer to us if we carefully trace the steps of the cosmogonic process.

The main ontological difference in religion is the creator-creation pair, God and the world. God is eternal, unchanging, primordial, uncreated. The world is placed in time, that is, finite, limited, and created. This is the basis of theology and the whole Church tradition.

In addition to this main distinction, however, we should already distinguish at least two levels, two sections—the corporeal and the spiritual. We are talking about the created spirit, not the Holy Spirit, who is God and the Third Person of the Holy Trinity. To this area of the spirit belong the heavenly paradise and the angelic ranks, as well as the assembly of those holy people who, through their faith, their exploits, works and deeds, have attained the spirit, having been transformed into a new nature—have become in the full sense of the word “sons of light.”

The other zone of the created world is the corporeal realms, denser and grosser than the spiritual worlds.

The laws of time and space apply to bodily creation and determine the life, forms, and timing of bodies and bodily phenomena. Spiritual worlds are governed by other laws. There is not what we understand by “time” and “space” as applied to the world of bodies. Spiritual worlds are creation, not God. Thus, in part they are like the corporeal world (they are created and finite), but in part they are closer to God Himself (there is no time and space). This is why Christ himself says, “the kingdom of God is within you.” This realm of the spirit is not subject to the laws of time and space (so it, being all-encompassing, is able to fit inside the human heart). Compared to the totality of the history of the corporeal world, the spiritual realm is eternal. Such are the angels—the intelligent spirits, the “second lights. They belong to this spiritual dimension—vertical in relation to the corporeal cosmos. They can be everywhere at once and at any moment. They are not subject to death and decay. But at the same time, they are fundamentally finite; they once were not and once will not be. It is said that “the heavens will pass away.” In the same way, spiritual creation will pass away. Compared to bodily creation it is eternal. Compared to God’s true eternity, it is finite and relative.

In the process of creation, the spiritual world comes first—it begins with it. Spiritual beings—angels—are created first and help God to order creation. The corporeal world—with time and space—is formed in the next stage. In the cross of creation, the vertical of created eternity is drawn first, and only then the horizontal of the corporeal world. Man is central to this cross—he stands in the center of the corporeal world and in the middle of the vertical of eternal creation—between the good and evil angels.

At the end of time, this process will take place in the opposite direction. First, the corporeal world will be elevated to the celestial-spiritual world and this is the moment of the resurrection of the dead. And then this resurrected—eternal—creation will appear before the Last Judgment. Horizontal time will ascend to vertical eternity.

Thus, the resurrection is not a return to earthly bodily life, but to the structures of spiritual creation. Hence the properties of resurrection physics of imperishability, power, glory, spirit. These same attributes are characteristic of angels. Christ responded to the Sadducees who denied the resurrection (Mk 12:25):

25 For when they shall rise again from the dead, they shall neither marry, nor be married, but are as the angels in heaven.

25 ὅταν γὰρ ἐκ νεκρῶν ἀναστῶσιν, οὔτε γαμοῦσιν οὔτε γαμίζονται, ἀλλ’ εἰσὶν ὡς ἄγγελοι ἐν τοῖς οὐρανοῖς·

This comparison does not imply immortality; but the resurrection body itself will change its nature, becoming a spiritual, heavenly body and imperishable (though finite) in comparison to ordinary earthly bodies.

Eternal Resurrection

Since the resurrection of the dead, or the changing of those living whom the Second Coming will catch on earth, precisely recreates a spiritual, eternal creation, it should be noted that the moment of resurrection cannot be uniquely coupled with the structure of time. Resurrection time does not come as ordinary time does. In a certain sense, it is a special time and accordingly this spiritual world of created eternity is always there—from the beginning of the world to the end. Likewise, there are always angels—spiritual beings. They do not come into the world as corporeal men and do not leave it. They are only visible or invisible. Likewise, there are people who will be resurrected. In order for them to be resurrected, they must already be—be in some sense always. Not necessarily in time and in body, but necessarily in conception, in their sense. In order to be resurrected someday, one must be resurrected always—in this vertical dimension, resurrected in the spirit.

This is precisely what Christianity asserts. Christ will not simply resurrect everyone by his rising from the dead—but has already resurrected everyone, because he has recreated, renewed creation, restored its spiritual structure.

In every human being, underneath the ordinary physics is the physics of the resurrection. Beneath the physical man is the spiritual man, belonging to the resurrection world, the Kingdom of Heaven.

The resurrection, while not an event in time, is an event in eternity, that is, it is always active. And so it is now.

The line between the living and the dead in the resurrection optics is erased. All are equally confronted with the fundamental problem of choice. Bodily life—precisely because of its extreme distance from God—offers unique opportunities to prove devotion to God—despite the fact that the very conditions of earthly existence compel one to deny His existence. But man cannot be completely devoid of mind and will, that is, of involvement in the world of the spirit. Otherwise, he would be a machine or an animal. Therefore, in the depths of every human soul there is an area of fundamental choice. This is the territory of the body of glory, the body of resurrection. It exists not only afterwards, but now, always. It is located—like the original Adam—on the vertical between the Archangel Michael (who is like God) and the fallen angel, the devil, the Danite, the “son of the dawn.” It is this ontological location of his heart—on the line of eternal creation and, accordingly, in the realm of the resurrection—that makes man human.

Eschatological anthropology does not refer to the future in the usual sense, but to the eternal present.

Importantly, the Creed speaks of the Second Coming of Jesus Christ:

and will come again with glory to judge the quick and the dead

Καὶ πάλιν ἐρχόμενον μετὰ δόξης κρῖναι ζῶντας καὶ νεκρούς

Here it should be pointed out that Christ will also judge the “living,” not just the resurrected dead. But these will be special “living” ones—already “changed” (ἀλλαγγησόμεθα—from the verb ἀλλάσσω), according to the Apostle. What is this change?

It restores man’s “body of glory,” his “spiritual body,” without him having to go through three successive phases—birth in body, death, resurrection. Such a change, albeit as an extreme case, is possible precisely because of man’s inherent nature of “creaturely eternity.” At the deepest level of his being, he is already resurrected, and it is possible to actualize this “resurrection” either through death or bypassing it. Saints, martyrs, and those Christians who have most fully developed their Christian identity are able to approach this state of “resurrection” even before the Last Judgment. Associated with this is the appearance of imperishable relics and other relics. The very bodies of the saints are transformed, falling out from under the material conditions of time. This means that the spiritual man, the man of power, the body of glory, is already in everyone, and this is the way of the Christian—to change while still alive, so as to come as close as possible to the ontological conditions of the Last Judgment. We must try to stand before that Court as early as possible, without waiting for the fulfillment of time. And the very will to change human nature accordingly brings closer the Second Coming of the Savior.

Such a change in life means becoming a “son of light,” awakening and irrevocably separating one’s destiny from the “sons of darkness,” from the state of meaningless and insensitive sleep.

Modernity Through the Eyes of Tradition

Now let us turn to a completely different section of anthropology—to the way modern Western philosophy and science present man, his essence and nature. We practically always start with modern notions, which we take for granted (“progress obliges”), and through their prism we turn to other—for example, pre-modernist—notions. This is done with a certain amount of condescension. If we do this, then any religious anthropology, and especially its eschatological section, will look like naive and arbitrary generalizations. But here’s the interesting thing. If we look from the opposite side and try to assess the anthropological theories of modernity through the eyes of a man of Tradition, a shocking picture will open before us.

If history is a process of splitting humanity into sheep and goats, i.e., actualization through a sequence of acts of free choice of people’s will towards in the sons of light or the sons of darkness, the last centuries of Western European civilization, retreating further from God, religion, faith, Christianity and eternity, will look like a continuous and worsening process of sliding into the abyss, a massive transition to the Danica side, a conscious and structurally verified vector of direct God-fighting. European Modernity is the way of the goats; that is, the compulsive invitation to societies and peoples to become scapegoats at the Last Judgment. From the very beginning, Western European civilization of the New Age has been built on a rejection of religion, first through the relativization of its teachings (deism) and later through outright dogmatic atheism. Man is now thought of as an independent material-psychical phenomenon, a bearer of rationality. God appears as an abstract hypothesis. In New Age culture, it is not God who creates man, but man invents “God” for himself in a naive search to explain the origin of the world. This approach leaves no place at all for spiritual worlds or angels in existence. All spirituality is reduced to the human mind.

In parallel, the very act of creation and created eternity are rejected. The idea of the structure of time and history changes accordingly. Heaven and the Last Judgment are presented as “naive myths” that do not deserve any serious attention. The emergence of man is described as a stage in the evolution of animal species, and human history as a gradual social progress leading to ever more perfect forms of social organization with ever-increasing levels of comfort and technical development.

This picture of the explanation of the world and man is so familiar to us that we rarely think about its origins and the assumptions on which it is based. But if we nevertheless turn to them, we see that it is a radical rejection of the ontology of salvation, a desire to categorically forbid man to create his being in the realm of eschatological sheep. The New Age paradigm turns its back on God and Heaven, and accordingly moves inward. In religious topology, it is an unequivocal choice of hell, a slide into the abyss of Abaddon. And beneath the formally atheistic and secular world order, the image of the fallen angel, which is the true origin of God-fighting initiatives, is becoming increasingly clear. The devil draws humanity to himself at all stages of sacred history, beginning with the earthly paradise. But to the full extent he manages to seize power over mankind and become the true “prince of this world” and “the god of this age” only in New Age.

Postmodernity: The Return of the Devil

The transformation of anthropology in an openly satanic vein is particularly evident in its later stages, in what is usually called the Postmodern. Here New Age optimism is replaced by pessimism, and humanism is abandoned altogether. If the New Age (Modern) rebelled against God, religion, and sacredness, the Postmodern goes further and calls for the elimination of man (anthropocentrism), scientific rationality and the final destruction of social institutions—states, families—up to the rejection of gender (gender politics) and the transition to transhumanism (transferring the initiative to Artificial Intelligence, creating chimeras and cyborgs through genetic engineering, etc.). If in Modernity the movement towards the civilization of the devil was outlined and expressed in the dismantling of traditional society, Postmodernity brings this trend to its logical end, directly implementing the program for the final abolition of humanity.

The program of the final transition to the object as a triumph of materialism is especially and vividly presented in the modern direction of Western philosophy—critical realism or object-oriented ontology (OO). It openly proclaims the demolition of subjectivity and an appeal to the Absolute External (Quentin Meillassoux) as the last foundation of reality. At the same time, many philosophers of this school directly identify this figure of the Absolute External with Satan or his counterparts in other religions—in particular, with Ahriman of Zoroastrianism (Reza Negarestani).

Thus, collectively, Modern and Postmodern represent a single trend aimed at placing humanity on the path of the rejected victim, the scapegoat, and by the time of the Last Judgment, which is denied, let it fall into the abyss of irreversible damnation.

The denial of religious anthropology and its eschatological apotheosis already contains a program of scapegoating, and as secular culture becomes more entrenched, developed and explicit, especially in Postmodernity and Transhumanism, this program becomes explicit and transparent. We can say, in simplified terms, that at first the New Age mocks the existence of God and the devil, rejecting the existence of the vertical as the axis of creation; and then in Postmodernism the devil and the lower half of the vertical return and make themselves known in full. But there is no longer a God (“God is dead,” cried Nietzsche, “we have killed him, you and I”) who could help humanity. He was discarded at a previous stage; this remains unchallenged in the Postmodern. All that remains is the devil, leading humanity down the broad road of damnation, cynically (Satan likes to joke) called “progress.”

The Armageddon of Our Hearts

If we now combine these two perspectives, eschatological anthropology and the conceptions of man in Modernity and especially in Postmodernity, we get quite a comprehensive picture. It will become evident that we are in the final stage of the end times in the immediate vicinity of the moment of the Last Judgment. There is nothing arbitrary or speculative in this statement. If we take the vertical of the world into account, this is the position humanity is in at every moment of its history: the Last Judgment and the resurrection of the dead are always close to man at every moment and in every place of his existence. But in the general dimension as applied to all mankind this event takes place once and for all—when both dimensions, the vertical and the horizontal, meet in the most complete and unvarnished way. And if at the Final Judgment whole masses of people happen to be totally unprepared for this, and moreover have been brought up in the attitude that nothing like this can happen, because only matter and its material derivatives exist, they are very likely to be among those who will be sent into the abyss. This is especially true of those who, succumbing to the hypnosis of progress, will go so far down the road of dehumanization that they will completely lose touch with human nature itself, and thus with the possibility of choosing the good part, which is always possible while we are dealing with humans—however difficult that choice might be in certain circumstances. But when the transhumanist project is fully realized and humanity irreversibly migrates into the zone of posthumanity (this is what modern futurologists call the Singularity moment), severing ties with its nature, the world and history will end, as witnesses will be removed from the center of reality. At the same time there will be no emptiness, but the exposure of eternal creation and the angelic vertical in its entirety—this will be the moment of the Second Coming, the resurrection of the dead and the Last Judgment. Until this happens, the division of humanity into sheep and goats acquires a particularly intense dramatic expression.

The masses are increasingly becoming “sons of darkness,” turning away from faith in the true divine light. They are opposed by the “sons of light,” who remain faithful to God, to the Savior, to the vertical. Both of them, despite the fact that the figure of the angel has long ago disappeared from the holistic picture of the world, consciously or not, find themselves extremely close to the angelic poles, separated from eternity and to the end of the world, as far away from each other as possible. For the goats, this means that they become literally possessed by the devil, turning into his helpless instrument and losing all autonomy. This is what it means to become “sons of darkness,” scapegoats, God’s rejected sacrifice. But it is also extremely difficult to remain faithful to heaven and light in such an extreme situation, and this desperate situation of the “little flock” needs the special support and guardianship of God and the guardian angels. At some point, the everlasting vertical battle of angels coincides with the last war of mankind, in which the “children of light” meet directly with the “children of darkness” in the immediate run-up to the Last Judgment. This is what is described in the Bible as the battle of Armageddon. It is impossible to describe it in purely earthly, rational terms, because it includes the ultimate volumes of theological, metaphysical, and ontological content.

The SMO has the most direct relation to eschatological anthropology. No one knows the exact timeline, especially because we are not talking about an event placed in time, but about that hard-to-imagine state of the world in which time directly collides with eternity, and accordingly, forever ceases to be the time it was before. Here begins the “future age,” facing along the vertical of being. Subliminally all this has already happened and is happening now, but it will be fully revealed in the Apocalypse, which in Greek means “revelation,” “discovery.” The hidden becomes manifest. This is how the mystery of man’s duality is resolved. And every person becomes a direct and immediate participant in it—because the front line runs not only in earthly geography, but strictly through our hearts.

Alexander Dugin is a widely-known and influential Russian philosopher. His most famous work is The Fourth Political Theory (a book banned by major book retailers), in which he proposes a new polity, one that transcends liberal democracy, Marxism and fascism. He has also introduced and developed the idea of Eurasianism, rooted in traditionalism. This article appears through the kind courtesy of Geopolitica.

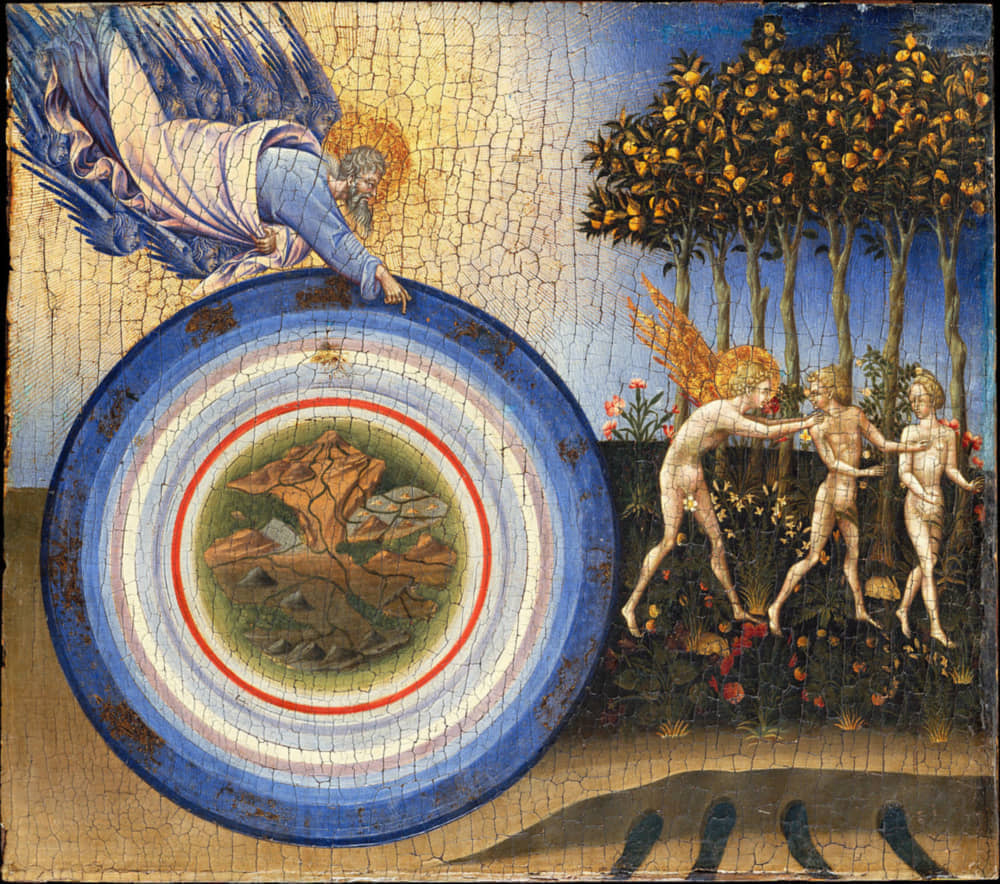

Featured: The Last Judgement, by Fra Angelico; painted ca. 1435—1440.