Christianity has become a minority religion in Europe, the place of its influence: how did this come about and what is the future of Christians in the West? Why are there so few Christians in the West?

” For many walk, of whom I have told you often (and now tell you weeping), that they are enemies of the cross of Christ; Whose end is destruction; whose God is their belly; and whose glory is in their shame; who mind earthly things” (Phil 3:18-19). Do these lines of St. Paul, written two thousand years ago, not apply to our present world? Let us add this question asked by Christ: ” But yet the Son of man, when he cometh, shall he find, think you, faith on earth?” (Lk 18:8). These words challenge us, when the question of God seems to be of little interest to Westerners, when they are in the minority in believing in God and even less in practicing what the religion of their fathers prescribes for them, even though no one here can ignore the existence of Christianity, even though many people are unaware of what it actually is and what it teaches.

Many books have been written on the reasons for the de-Christianization of the West, its secularization and the fall in the number of practicing Catholics. External and internal causes are usually put forward. Among the former, we can largely mention the long movement of emancipation of man from his traditional dependencies (God, nature, culture), with the nominalist revolution and the affirmation of sovereign reason from the Renaissance onwards; thus, without denying faith at first, God was progressively put aside. At the personal level on the one hand, the rise of individualism, to the detriment of holism, caused a dissociation between spiritual life, belonging to the private sphere, and public life. [In politics, holism refers to a society where the group, the whole, predominates over the individual, the part.]

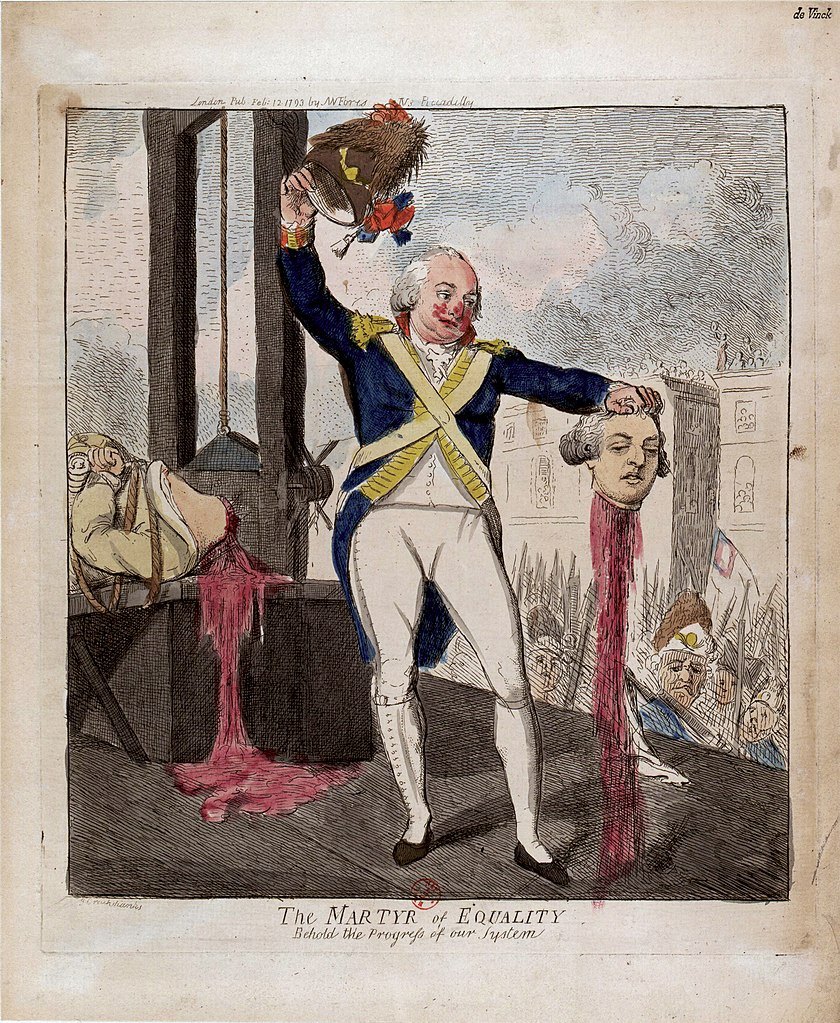

At the political level, on the other hand, a clear separation between the temporal and spiritual orders was established, giving total primacy to the former. With the French Revolution and the disappearance of “Christendom,” the movement accelerated and sometimes took on a strong anti-Christian tone, as in France with the secular laws that led to the 1905 separation. At that moment, God’s sovereignty over the city was largely destroyed—there yet remained to destroy the sovereignty of the natural moral law and the heritage of culture so that the will of man would no longer have any obstacle. We are there today, gender theory and Wokism being the final stages of the deconstruction of the classical anthropology shaped by Christianity.

On the side of internal causes, by oversimplifying, two types of explanations clash. The “progressives,” who had hoped that the Second Vatican Council (1962-1965) would mark a clean break with the past, believe that the decline of Catholicism is due to the Church’s still reactionary positions, positions that are not understood by our contemporaries; they therefore advocate an opening to the world and its demands, especially moral ones (contraception, abortion, same-sex marriage, abolition of celibacy for priests and desacralization of the office, ordination of women, etc.). Some “traditionalists” defend the exact opposite point of view: Vatican II caused a rupture in the Church’s Magisterium and in its liturgy, a rupture caused by a rejection of the past and an excessive openness to the world, which manifested itself in a generalized stampede that explains the sharp drop in religious practice and vocations; the remedy would be a “forgetting” of Vatican II and a certain return to the pre-conciliar Church. Between these two somewhat caricatural extremes, there are all kinds of nuances, including those who consider internal causes to be negligible.

External justifications have certainly played a major role in the decline of Christianity in Europe. As for the internal causes, the “progressive” explanations are far from reality. This does not validate the opposite thesis, which holds Vatican II responsible for the Church’s ills: rather than seeing in the Council a “break” with the past, we believe with Benedict XVI that it marked a necessary “renewal in continuity.” The post-conciliar drifts, which are real, have undoubtedly had an influence on the crisis in the Church, but they are not sufficient to understand its extent, since the other Christian confessions have undergone an equally rapid decline without a council or liturgical reform. My purpose here, however, is not to discuss the correctness or otherwise of these statements, but to suggest another key to understanding the crisis; one that is by no means contradictory, but on the contrary complementary to the explanations that have just been briefly mentioned.

“Real” Christians Always in the Minority?

The question is, why has the West become the only place in the world where religion has been evicted from the public sphere, where the question of God has been evacuated from official bodies, where the number of practicing Catholics is around 1 to 2%, whereas once upon a time in Europe there was a “Christendom” where 95% of the population was baptized? The idea to be discussed is the following: in any era, have not the people who really, deeply and freely live the Christian faith always formed a small minority, even in a system of Christianity? In other words, don’t most of them follow the external requirements of the dominant religion, under social pressure or habit? This is what Pierre Manent seems to think in his latest book on Pascal: “For those who look at things coldly, the most significant fact would not be the authority acquired by Christianity, but, on the contrary, the theoretical or practical atheism of the immense majority of human beings, including Christians.” If this intuition is correct, this does not mean that Christianity is reserved for an “elite” as if it were a gnosis; on the contrary, and history proves it, it is addressed, as the Gospel affirms, to those who recognize themselves as “little” and not to those who claim to be “wise” or “intelligent” (cf. Mt 11:25 and Lk 10:21).

In the course of history, a religion has only imposed itself durably on peoples through political support, exerting a certain social pressure, within the framework of holistic societies where the group took precedence over the individual. Globally, Christianity does not escape this pattern. Its vocation, as Christ has shown us, is to spread, not by force of arms, but by preaching, without violating consciences, and even more by witnessing to the point of martyrdom. This “poor” way of operating leads to free and profound conversions, but always in a minority. Even the passage of God made Man on earth did not bring about massive adhesions: although God became incarnate in Jesus, most of His contemporaries did not embrace His teaching. Some theologians have seen in the episode of the ten lepers healed by Christ, only one of whom returned to thank Him (cf. Lk 17:11-19) the image of faith, which is shared by only a small percentage of men (10% here). When Constantine promulgated the Edict of Tolerance of Milan (313), Christians represented 5% of the population of the Empire; a rate that varied, however, according to the territory: Rome, the most Christianized city in Italy, had about 10% of Christians; they were around 20% in Egypt, 10 to 20% in Africa and 30% in Asia Minor. And whenever evangelization has been carried out in this spirit, as in Asia from the 16th century onwards, i.e., without any political support, the fruits have been magnificent, revealing an admirable faith and great courage among the converts—but they have always represented only a small part of the population.

It could be rightly argued that in these last cases of evangelization, Christians remained a minority because of the hostility of the political authorities towards the Church, which often went so far as to carry out terrible persecutions to try to eradicate it.

In short, Christianity only began to gather large sections of the population when politics did not threaten it, and even more when it supported it. After the Edict of Milan, which instituted a kind of religious freedom, Christianity spread, including in the upper echelons of the state. A “neutral” political power in religious matters having never really existed, the Empire, under Theodosius, ended up making the religion that had become dominant the state religion (edict of Thessalonica in 380). Thus, Christianity inaugurated a new status, that of the Christian State, where temporal power and spiritual power were both linked and yet distinct, in a balance of power that would continue to vary over the centuries.

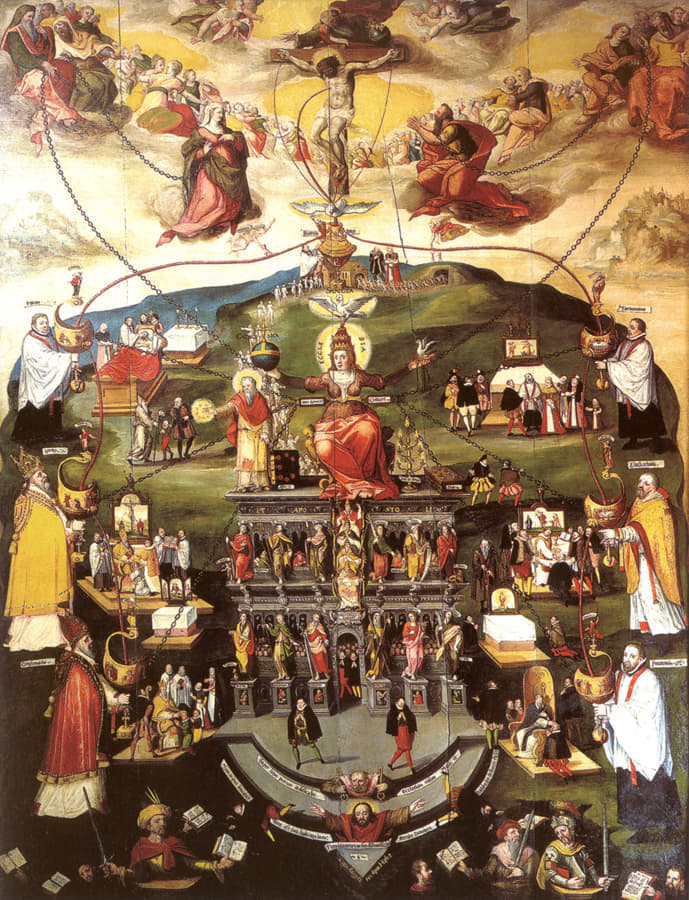

Christianity

Thus was established in Europe “Christendom;” history forged two different systems in the East and in the West. Byzantium, in the East, heir to the Roman Empire, after the fall of Rome, perpetuated a “caesaropapist” regime characterized by a Church largely subject to the emperor. In the West, the barbarian invasions destroyed the Empire and, with it, the central political power, opening the way to feudalism: in the chaos that settled in, the Church was the only bulwark, the only entity safeguarding knowledge and capable of transmitting it. Unlike in the East, the spiritual was more or less equal to the temporal. This led to a system in which each of the two powers retained its independence, the Church having to resist for a long time the attempt to take control of politics, hence the endless quarrels that ran through Western Christendom. In both cases, however, the Christian faith was defended by princes who were themselves Christians; in these holistic societies, the unity of religion was an essential factor of the temporal common good, which is why the attack on this unity was a common law offence that the political authority could repress, in the same way as offences such as theft – it is important to remember this when referring to an institution such as the Inquisition, in order to avoid any anachronism.

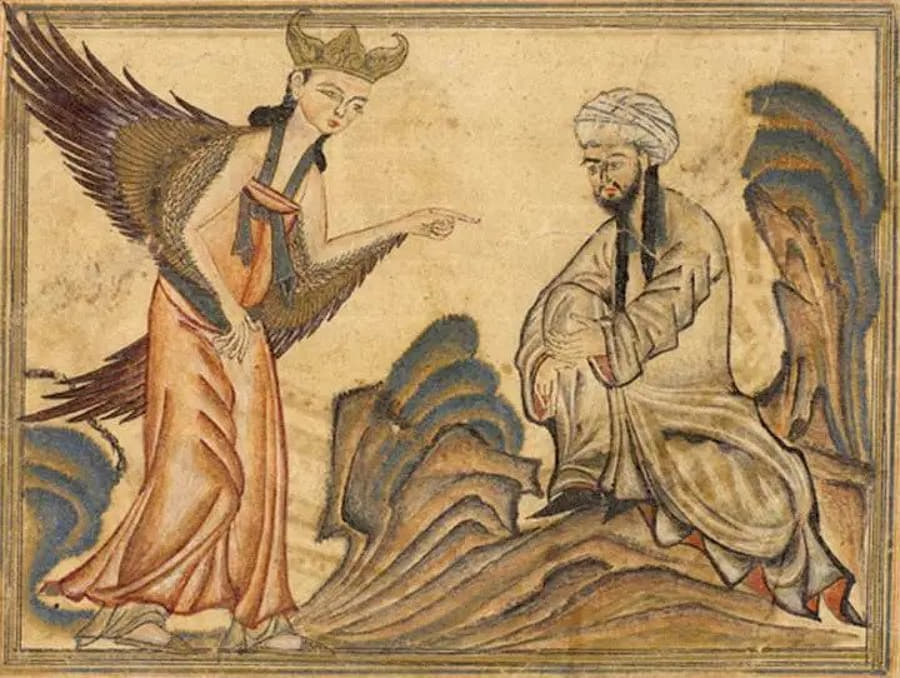

In “Christendom,” Christianity was the state religion—which does not mean that it was a “theocracy”—and the vast majority of the people could only be Christians, since social pressure was in that direction and non-Christians had an inferior status that did not allow them to exercise political responsibilities within the city. Until quite recently, all civilizations functioned more or less in this way, in a rather coercive manner, ignoring individual freedom and the dignity of the person. This is particularly true of Islam, which, unlike Christianity, has made little progress in these respects. [Theocracy in the sense of political authority exercised by the religious. Cardinal Charles Journet has shown that even a bull like Unam sanctam (1302) by Boniface VIII did not fit into this framework].

There is indeed an essential difference between Christianity and Islam which partly explains the evolution of Christian societies and the immobility of Muslim societies: Christianity is a religion of faith whereas Islam is a religion of law (Cf. Rémi Brague, The Law of God). In other words, adherence to Christianity is manifested by a personal act of faith that is supposed to be free and enlightened, i.e., by a gesture that deeply engages the whole person, including his or her conscience. Whereas it is sufficient to observe the law of Islam in its letter in order to be a Muslim. Thus, the Christian faith requires a much stronger commitment than obedience to an external law—even if the latter can be demanding, as during Ramadan. And this explains two essential things: why the concept of individual freedom, with its accompanying notion of personal dignity, could only emerge in Christian lands; and why, as soon as the social and political pressure imposing the state religion was relaxed, the religious practice of Christianity dropped sharply.

In other words, the aspiration to freedom, not only legitimate in itself, but also the undoubted fruit of authentic Christianity, has exploded the holistic societies of the Ancien Régime, which maintained religious unity through a certain social pressure incompatible with the new freedoms. Religious pluralism became inescapable. These political transformations, which owe much to Christianity and whose starting principle was sound, occurred in a context of often anti-Christian governments that had a false conception of freedom. If the desire for freedom is a spontaneous and legitimate impulse, it must be limited, especially by the natural moral law, and be at the service of the temporal common good. When this desire is no longer limited and the human will is left to its own devices, drifts are inevitable, as we see only too well today.

What Future?

This too brief historical detour provides some keys to understand the considerable decline of the Christian faith in the West and the low level of religious practice. Certainly, one can regret the positive aspects of Christianity, beautiful pages of our history having been written during this long period. But, in spite of the obvious drifts today, no one would want to return to a holistic society imposing a religious unity that would be largely artificial, and to renounce the positive contributions of modernity in terms of freedom, justice, and the functioning of a state of law. Because Christianity is a religion of faith, Christendom collapsed because it had become an “empty shell”: when the governing elite casually frees itself from common morality without being reprimanded by the high clergy (only two of the last Bourbons did not multiply their mistresses in the eyes of everyone), it is the sign of a regime that is no longer Christian in name only. [Perhaps Christianity would have endured if Christianity had been a religion of the law?]

History, however, shows that men live their faith better when politics and religion work together. Today, in Europe, the temporal and the spiritual are separated and Western regimes proclaim themselves “neutral” with regard to all beliefs, relegating Christianity, which has shaped our civilization, to the same level as other religions. In fact, this neutrality is largely illusory and every regime is driven by a philosophy that secretes its own morality. We have thus reached a situation where Christian morality is rejected in favor of a mortifying relativism that nevertheless has its own ethics and dogmas, which are very rigid, and which can be summed up in human rights and the “refusal of all discrimination.” The notions of good and common good have disappeared, our democracies being reduced to a procedural system that is supposed to guarantee to each one the faculty to pursue his own ends.

Such a system—without objective limits—inevitably leads the majority, or more precisely the active and organized minorities, to impose their ideology on all. In this unstable context, Christians are not oppressed; they benefit like everyone else from a real religious freedom. [Clauses of conscience are nevertheless violated.] But if they want to live their faith deeply, they are confronted with continuous daily worries, especially for the education of their children—they have to juggle constantly to get around the multiple disorders generated by this disruption of morals, to be more often than not against the current and vigilant to resist all sorts of poisons.

Christophe Geffroy publishes the journal La Nef, through whose kind courtesy we are publishing this article.

Featured: Ruin of a Church, by Rudolf von Alt; painted in 1849.