We are highly honored to present this conversation with Olivier Bonnassies, who is the co-author (with Michel-Yves Bolloré) of the recent and truly magisterial work, Dieu, la science, les preuves (God, Science, the Proofs). The work is a 600-page tour-de-force proof of God, drawing upon rational arguments and scientific evidence. The book throws down the gauntlet to atheism, leaving it little room to maneuver.

Olivier Bonnassies is a graduate of Polytechnique (X86), HEC (HEC start up institute) and the Institut Catholique de Paris. As an entrepreneur, he has created several companies. A non-believer until the age of 20, he is the author of some twenty books and videos and of several shows, scripts, articles, newsletters and websites on subjects often related to the rationality of faith.This interview comes through the kind generosity of our friends at La Nef.

La Nef (LN): How did you come to embark on the writing of such an imposing work on the current knowledge of the origins of the Universe and its consequences? And what skills do you have for such a work?

Olivier Bonnassies (OB): When I was 20, I was not a believer. I had studied science and was at the École Polytechnique. Then I set up my first company, which was starting to do well. But soon enough, I asked myself what it was all for. I asked myself the big questions: what is the meaning of life? What is its purpose? Where do we come from? Where are we going? I thought there were no answers to these questions, but I came across a book by Jean Daujat, a brilliant normalien, entitled, Y a-t-il une vérité (Is there any truth?) I was very surprised to find that he gave serious and very rational reasons to believe in God. I expected to find some flaw quickly. But, no. So, I decided to work seriously on the subject by doing four years of theology at the Institut Catholique de Paris to deepen my understanding. I became a Catholic, even though my family was very reluctant for me to do so. And in the years that followed, I continued along this path, trying to set up projects that made sense. That’s how I met Michel Yves, who helped with two intense projects: the construction of the Mary of Nazareth International Center in 2003, which has been one of the very first places of attraction in northern Israel for the past ten years, and the creation of the Aleteia news website in 2010, which has become the first Catholic website in the world.

In 2013, I gave a presentation on these topics to a senior high school philosophy class where my daughters were, which I recorded: it resulted in the video, ” Démonstration de l’existence de Dieu et raisons de croire chrétiennes” (Demonstrating the Existence of God and Christian Reasons to Believe)” which has 1.5 million views on YouTube. Michel Yves saw it and sent me an e-mail to tell me that it was very good, but that we could do much better, and that he had also been working on the subject for thirty years. So, we brainstormed about a collaboration, and then got to work in 2018. We dug into the subject again and again, with the help of about twenty good specialists. I hope that the surprise I had at 20 will be the surprise of the book’s readers—because there is indeed a body of converging, rational, and independent evidence that God exists.

LN: Formally, science explains the “how,” not the “why,” a role that belongs to philosophy. As such, science cannot “prove” the existence of God. Isn’t there a risk of confusion of genres and a methodological problem in using science to “prove” God?

OB: This is a question that often comes up, and it is important to take the time to answer it properly, even if there is the question of vocabulary and definition behind it.

For some people, the word “science” has been understood progressively in a more and more restrictive way, up to Popper’s criteria, which claim to exclude from it everything that is not falsifiable. But for the general public and in classical logic, science is first of all what scientists practice in a field of knowledge, and it is above all logos (rationality) applied to this field of knowledge, as the etymology of the name of most of the sciences clearly shows (in “-logy”). [Biology is rationality (logos) applied to the living; as well as cosmology, archaeology, geology, psychology, paleontology, ecology, oceanology, oncology, cardiology, dermatology, neurology, pharmacology, climatology, criminology, futurology, graphology, demonology, epistemology, ethnology, eschatology, theology, ontology, ophthalmology, etc.

The basis of science is the logos. And this is also true of logic!]

Today, there is also something new: it is the fact that many modern scientists feel the need to talk about God at the end of their scientific practices, especially when they explore the beginnings of the Universe and its fine tuning. This is how we were able to gather in our book dozens and dozens of quotes from Nobel Prize winners and great contemporary scientists who naturally come to talk about God in direct connection with their scientific research and discoveries. This is why it is difficult to say categorically on the basis of purely theoretical arguments that God is not within the scope of science and that it does not encounter Him.

Here is the summary, in two points, of the argument about the beginning:

- There was certainly an absolute beginning to time, space and matter, which are linked as Einstein showed. This is established by rationality (page 61 and page 91 and pages 515-517 of the book), thermodynamics (pages 55-72) and cosmology (pages 100, 165, 206, 210, 214, with in particular the Borde-Guth-Vilenkin theorem), the Big Bang not necessarily being this absolute beginning even if it constitutes a very good illustration of it;

- The cause at the origin of this radical emergence is thus by definition non-temporal, non-spatial and non-material (page 91-92) and it had the power to generate everything and to regulate everything infinitely, precisely so that the atoms, the stars and man could exist.

With this very simple reasoning, we arrive quite exactly at the definition of what all philosophies and all classical religions call God. But at what point did we leave science? If you say that it is at point 2, isn’t it the characteristic of science to look for an explanation to emerging phenomena? Isn’t the principle of causality really part of science, the foundation of science?

From moment point on, the concrete problem for scientists, who want to remain atheists, is that they have to contest one of these two points, but it is not easy:

- Some like Andrei Linde will try to deny the first one by imagining an “eternal inflation of bubble Universes.” But this is very speculative, unverifiable, and quite flawed, especially because it is increasingly clear, thanks to mathematics and physics, that infinity does not exist in the real world (see note on page 206).

- Others like Stephen Hawking and Laurence Krauss will try to explain the cause or absence of cause by reasoning that is also very flawed, as is jokingly recounted in the book (page 168).

But beyond the fact that the atheist position is very hard to defend, it should be noted that the protagonists of these debates on the existence of God are neither philosophers nor sorcerers, but that they are all scientists who think they are looking for solutions within science.

It is therefore not right to make too tight a separation between science and philosophy. Plato, Aristotle, Newton, Leibniz and so many others did not set up such barriers between science, philosophy, metaphysics or theology. The separation of genres has only existed since the 17th century; but most of the early Greek philosophers were scientists. They all worked from this fundamental Logos; and their opponents were not the scientists, but the poets, who were interested in the Pathos. And it is on this Logos that all the sciences were established, including philosophy, which for a long time was called the “queen of sciences.”

[Science is rationality (Logos) applied to a field. Physics is rationality applied to the material world. Biology is rationality applied to the living world. The same goes for the other sciences: cosmology, archaeology, geology, psychology, paleontology, ecology, oceanology, oncology, cardiology, dermatology, neurology, pharmacology, climatology, criminology, futurology, graphology, demonology, epistemology, ethnology, eschatology, theology, ontology, ophthalmology, etc. Ditto with ideology, oenology, astrology, parapsychology, mythology, ufology… and logic (from Logos).]

Secondly, we must understand that science itself is full of philosophical principles. For example, if we remove the idea that the world is logical, rational and understandable, or the principle of causality, which is also a philosophical principle, or the principle of stability of laws, which is also a philosophical principle, we cannot do science anymore. Science stops.

Thirdly, it is necessary to see that, in their practice of science, the great scientists cheerfully mix theories, figures, equations and interpretations which belong, in all rigor of the term, to the domain of philosophy. But wouldn’t it be absurd to separate this from science? When Newton talks about “force,” when Maxwell talks about “field,” or when Bohr or Einstein discuss interpretations of quantum mechanics, they are in a way doing philosophy within science—but they are doing it in a very legitimate way, of course.

Fourthly, it is more and more clear that modern science, in all fields, opens up to a beyond of science, of which it cannot say anything—except that it exists. Everything that is tangible, calculable, observable, leads, within its own rational analysis, to the existence of something that is intangible, unobservable—but nevertheless necessary. This is explained on page 92, note 56: “If one analyzes footprints on sand, one can, within physical science, affirm that there is a cause for these footprints that do not come from the natural interactions of physical forces.

In the same way, when Alain Aspect’s experiment concludes that there is an entanglement between two particles that are 14 meters away from each other and that dialogue instantaneously, we demonstrate within physical science that there is something outside our space-time. It is still the case when Gödel, inside logic and the mathematical logics, concludes that there are necessarily non-demonstrable truths, which refer to an exterior of mathematics. The same type of “apophatic” reasoning also applies to the Big Bang, within cosmological science itself.”

Finally, it is very important to acknowledge the fact that today, science has invaded the field of metaphysics and that it is no longer possible to do serious philosophy without taking into account what science has brought about time, space, matter, vacuum, mass, atoms, reality, the beginning and the end of the universe, etc. For example, the word “atom” comes from the pre-Socratic atomists, Leucippus and Democritus, and then from the Latins like Epicurus; and it has been taken up by many philosophers after them.

But when, in 1905, Jean Perrin discovered the atom experimentally in Paris, and then its profound reality was revealed, we saw that the atom did not resemble at all that of the Greeks and of all the philosophers, who imagined it to be unbreakable, compact, etc. The atom of the real world has none of the properties that the ancients had attributed to it. A little later, science showed that time is relative to gravity and speed. This is now a proven reality, but no philosopher of the past had ever imagined this either. Can we therefore continue to do philosophy without science or outside of science? No!

In a letter from 1936, Einstein explains that there are many situations in which physicists today are led to enter into philosophy and do the work of a philosopher, because philosophers themselves cannot do it: “It has often been said, not without reason, that natural scientists are poor philosophers. If this were so, would it not be better for the physicist to leave philosophizing to the philosopher? This may be true in times when physicists believe they have a solid and unquestioned system of fundamental concepts and laws, but it is not so in times when the whole foundation of physics is being questioned, as it is today. In such an age, when experience forces him to look for new and unshakable foundations, the physicist cannot simply leave to philosophy the critical examination of the foundations of his science, because he is the best placed to know and feel where the problem lies.”

So, scientists naturally do philosophy within science. This is a fact; and it is wrong to say that science cannot prove anything. Concerning the beginning of the Universe and its setting in particular, science leads to three very clear conclusions:

There was a Big Bang. It is certain. It is possible to describe precisely what happened from 1 second (CERN has made it possible to go that far).

To describe positively what happened before is not possible at present. It may even remain forever impossible and outside our experience before 10-43 seconds: there are only very speculative hypotheses on these subjects, on which there is no consensus.

On the other hand, it is possible, on the basis of rationality, thermodynamics and cosmology (according to the Borde-Guth-Vilenkin theorem—the Big Bang not necessarily being the absolute beginning), to affirm that there was an absolute beginning to time, space and matter; and therefore that the cause at the origin of this emergence is transcendent, non-material, non-spatial, non-temporal, endowed with the power to create and adjust everything. Now, this third conclusion is very important, because it is very close to what all philosophies and classical religions have always called “God.”

Science can therefore contribute to giving proofs of the existence of God.

These are real proofs, but they are “apophatic;” that is to say that we are talking about realities whose existence can only be deduced indirectly and which we can only qualify in a negative way, without having any direct positive knowledge of the nature of the causes in question. In spite of this, we can affirm with certainty the existence of these causes.

And we must also agree on the word “proof” which has a clear definition. A proof is, in a trial, “what serves to establish that something is true” (Google/Robert), a “material element” (Larousse) that allows to accredit a thesis and to invalidate its opposite; or “a fact or a reasoning that can solidly establish the truth” (Wikipedia). Thus, real-world evidence is never “irrefutable” or “absolute.” They are elements that accumulate in favor of a thesis with more or less strength. One can demonstrate that someone is guilty or innocent with such evidence; but it is not a matter of mathematical demonstration, nor of logical evidence, nor of certainties of the “checkmate-in-three-moves” type. On the other hand, when strong, convergent, rational evidence from independent fields accumulates, we arrive at a certainty “beyond all reasonable doubt,” as we say in the legal world.

This is exactly what we arrive at in our rational inquiry, which deals with a dozen independent fields, some of which are scientific, others not.

In short, the a priori theoretical distinctions do not hold; and, to see this, we must look at the real world. There are many a priori, prejudices, preconceived ideas. We have to be careful with these too-theoretical positions which are not right and which are upset by reality, such as: “Science is the “How?” and religion the “Why?” No, science and religion or philosophy are not “two separate magisterial,” as Stephen Jay Gould theorized with his “NOMA” (Non-Overlapping Magisterium). This is not true, as are many other preconceptions such as “science cannot say anything about God;” “it is impossible to prove God;” “if God could be proved, there would be no room for faith;” “if God could be proved, it would be the death of religions;” etc. All these preconceptions are not true. All these preconceived ideas are false.

The only people who believe them are materialists and fideists, for opposite reasons. Materialists think that religion has nothing to say about the real world, and fideists doubt natural reason and its reliability. But all this does not hold. Why not? Simply because if religion claims to speak about the real world and claims to be embodied in history, then there are many places where it interacts with science. If the Gospel says that there is “in Jerusalem, near the Sheep Gate, a pool called Bethzatha in Hebrew, which has five colonnades” (Jn 5:2) and that archaeology confirms this, this is not concordism, it is simply the fact that the Gospel is based on historical realities. And if the Hebrew people say that they believe by revelation that the universe began, that it was created out of nothing, that there are no demigods or sub-humans, and that no god dwells in springs, forests or pieces of wood, this is important because these are indispensable truths for men to have a true relationship with God. But of course, for this relationship to God to be true, it is important that all of this be consistent with reality.

LN: Some of our fellow citizens do not believe in God, not so much out of deep conviction as because they live in a materialistic context that does not encourage it. Do you think that recourse to science can convince these people? What audience, precisely, is your book aimed at?

OB: This book is not only for the curious: it is for everyone, because the question of the existence of God is one that everyone asks themselves one day or another. Nowadays, there are really good reasons to reopen the file rationally, to discover all its elements, to think about it. This book is an invitation to reflection and debate.

LN: You bring us to recognize the existence of God by showing that the Universe, having a beginning (the Big Bang), was created. In what way does a created Universe oblige us to postulate the existence of God?

OB: To say that everything has a cause is perfectly false—there is necessarily at least one necessary being who gives cause to everything that exists. It is easy to realize this by considering the whole of all the beings that exist. This whole cannot have a cause outside itself. Now, to be the cause of oneself is not possible. It is therefore that there is necessarily at least one necessary being. This is true at every moment, to give existence to everything that exists (vertical causality) but it is also true in time (horizontal causality). This is how all atheistic materialist doctrines, from Parmenides, Heraclitus, Democritus or Lucretius (author of the famous formula “ex nihilo nihil”) to Marx, Friedrich Engels, Lenin, Mao and Hitler, through Friedrich Nietzsche, Arthur Schopenhauer, Ludwig Feuerbach, David Hume, Jean-Paul Sartre and all the atheistic philosophers of the 19th century—or Baruch Spinoza, Auguste Comte, Ernst Mach, Svante Arrhenius, Ernst Haeckel, Marcelin Berthelot, Bertrand Russell, Francis Crick and all the atheist scientists of the pre-1960s—all of them always imagined that matter was somehow eternal in the past and that the Universe had never begun. But this position, which has never been rational, is less than ever tenable after modern scientific discoveries (thermodynamics, cosmology and the Big Bang illustration). Only God remains if we want to remain reasonable.

Note 54 on page 91 of the book shows why an infinite time in the past is impossible. Because if we count 0, 1, 2, 3… without ever stopping, we go towards infinity, but it will always remain a potential infinity that we will never reach. Thus, in mirror image, for the same reason that we cannot reach infinity in the future starting from today; we cannot start from infinity in the past to reach our time either: an infinite time in the past is therefore impossible (see the third point entitled “The Creator of time” in chapter 22). Today, science confirms this point that scientists did not accept one hundred years ago. Science has shown that space, time and matter had an absolute beginning. Through Relativity, Einstein showed that space, time and matter are inseparably linked and that one cannot exist without the other two. Thermodynamics has shown that entropy increases and leads, after a certain time, to the thermal death of the Universe, which cannot be infinite in the past. Cosmology, with the Borde-Guth-Vilenkin theorem, which is based on the work of Penrose and Hawking on singularities, shows that there is necessarily an absolute beginning to the Universe. But the Big Bang, now confirmed, is not the proof of the beginning. It is only a good illustration of this absolute beginning.

LN: If science demonstrates the fact of the creation of the Universe, what does it teach us about how this creation took place, including, for example, the controversial question of evolution?

OB: This question is controversial, as you say. That is why we did not deal with it in our survey, which needed to select the discriminating questions, i.e., those on which one can easily make a decision. On evolution, there are two visions: the vision of Darwin and his (numerous) followers, according to which natural selection explains everything; and the vision of those who think that this principle is valid but that it does not explain everything. Those who are interested can read Life’s Solution by Simon Conway Morris, who presents seventy examples of convergence of complex organs, such as the human eye, and who concludes in a very convincing way that the laws of the Universe program the coming of man since the Big Bang.

LN: The second part of the book chooses to seek concordance between the Bible and science, insisting on coherence when there is any, and explaining, when there seems to be a contradiction; that it is necessary to depart from the literal meaning. Is there not a risk of concordism here, and would it not have been preferable to center this part on the astonishing fact that the Jewish people were the only people of antiquity to affirm a faith in a unique God transcending a physical universe created by Him?

OB: If we assume that creation and revelation have the same origin, then “concordism” is more likely to bring us closer to the truth than an overly “discordist” approach. But two things must be kept in mind which may seem to be in opposition. First, it is true that the purpose of the Bible is not primarily to give us a scientifically accurate account or a historical account in the modern sense of the term (which would not be of much interest), but to allow for a strong and truthful relationship with God. But secondly, Revelation speaks of the real world; it passes through truly historical events; and it is embodied in history. There are thus naturally many interactions between faith and reason which must concur on these points.

Why then this choice to speak about the Bible?

It is very strange to see that the Bible states truths that the Hebrew people knew but that all the other peoples—much more learned—were unaware of about God, men, nature and the Universe. It is also curious to see that the Jewish people are the only people of antiquity still present on Earth; or that a young man of 30, Jesus, who wrote nothing and died on a cross, became the one who had the most influence on the history of humanity, as Himself and the prophecies proclaimed. In this book, rationality is interrogated.

LN: The chapter on Fatima seems a little out of sync with the rest of the book. Why did you choose to devote a chapter to a Marian apparition?

OB: The miracle of Fatima (in 1917, in Portugal) is also, as we show in the book, a real, rational question about the existence of God. How is it that children announce, three months in advance, a miracle that everyone will be able to observe, at a very precise time? This well-documented event raises the question of whether it can be explained within a framework of materialist thought; that is, without a supernatural hypothesis.

LN: Doesn’t the great diversity of ethical systems throughout the world contradict the affirmation of the existence of a transcendent moral law common to humanity? Do not the consequences of original sin, which distort our moral judgment, prevent unanimity on this subject?

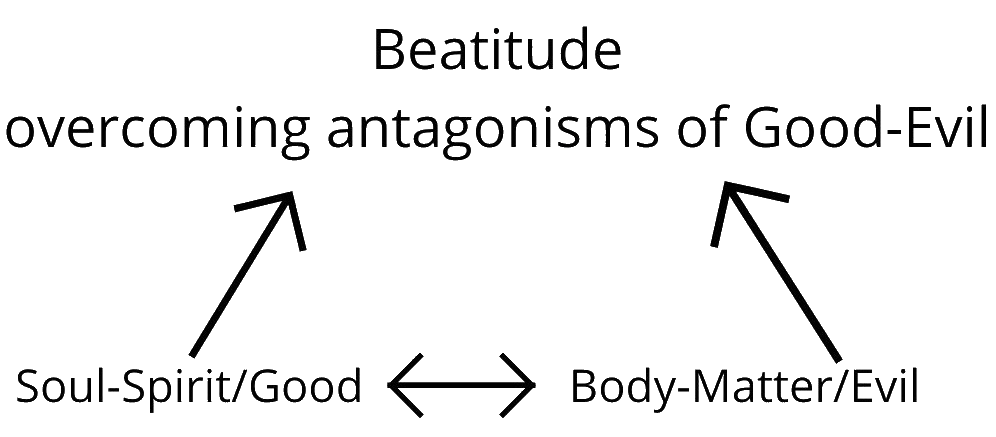

OB: Yes, but beyond this diversity, if there is no absolute outside the material Universe to found good and evil, then nothing can be sacred, absolute, good or intangible. In the case of a world without God, we are ultimately just an agglomeration of atoms, and crushing a child or a mosquito is ultimately equivalent: it is a simple reorganization of matter. Consistent atheists must believe this; but it is not easy.

LN: The answer to the objections of the materialists is particularly hurried on two of them, especially on the problem of evil. Why, in a book of nearly 600 pages, did it not go into this objection, which is the one usually put forward against the existence of God? Is it not because there is no totally satisfactory answer, since it remains a mystery?

OB: The objection “if there is a good and all-powerful God, evil is impossible” does not hold, either logically or in terms of probability. For the presupposition “if God is love, He must create a world without evil” is false. Serious atheists readily acknowledge this. To quote a few: “We may concede that the problem of evil does not, after all, demonstrate that the central doctrines of theism are logically inconsistent with each other” (John L. Mackie, atheist, 1982, The Miracle of Theism, Oxford University Press, p. 154). “Some philosophers have held that the existence of evil is logically inconsistent with the existence of a theistic God. No one, I think, has succeeded in establishing such an extravagant claim” (William L. Rowe, atheist, The Problem of Evil and Some Varieties of Atheism, 1979, p. 135). “It is now recognized on (almost) all sides that the logical argument is bankrupt (William P. Alston, “The Inductive Argument from Evil and the Human Cognitive Condition,” Philosophical Perspectives, Vol. 5, 1991, pp. 29-67).

Indeed, if God is love and if He seeks love, this presupposes free will. In reality, outside of Revelation, we are not in a position to judge whether God has or does not have good reasons for temporarily allowing suffering to exist in the world. Logical or intellectual arguments fall away, but the emotional issue remains very powerful. However, this is not the subject of our book, which does not talk about who God is, but only deals with one question: is there a creator God? And from only one angle: rationality.

LN: You devote a chapter to recalling the philosophical proofs of God’s existence (which have not changed since St. Thomas Aquinas), beginning by saying that they “have never interested anyone.” Why then devote space to them, and why are they of no interest to anyone if they are really convincing?

OB: Personally, the evidence I prefer is that of contingency. It seemed obvious to me that everything that exists must at every moment receive its existence from a cause; and that at every moment there is a first, necessary cause that maintains everything in existence. But after my conversion, I experienced that this proof did not convince many people. These philosophical proofs are very valid, but they don’t “make much of an impression;” i.e., they are not enough to convince. This is an observation. On the other hand, in addition to other elements, and in convergence with them, they are in my opinion very useful and contribute to establishing a rational and independent body of evidence.

LN: People often accuse believers of credulity; but you conclude, on the contrary, that it is materialism that is an irrational belief. Could you explain why?

OB: A coherent and rational materialist must believe that the Universe has always existed contrary to all evidence; that it is infinitely well-regulated by chance; that there is no good and evil; that the Bible, the destiny of the Hebrews, Jesus and the predictions of the children of Fatima, as well as the thousands of miracles and apparitions, the thousands of saints and the testimonies of personal encounters with God are also explained by illusions or by immense strokes of luck. This is really a lot to ask, and it is more than irrational. Everything converges. We must take the time to try to evaluate the probabilities. All this is actually impossible. It takes a lot of credulity to remain a materialist.

Featured image: “Creation of the Animals,” by Tintoretto; painted ca. 1551-1552.