That we are at the end of an age is clear. It remains to be seen what exactly are the opportunities and difficulties, the tragedies and hopes, of this moment. A taller order still is playing out the long-term consequences of the COVID-19 disruptions through society. Via the Corona disease the long-downtrodden West, indeed the world, may be experiencing a transition as regular – though seismic – as a “Fourth Turning” moment; or we may be witnessing birth pangs as profound and far-reaching as Rome’s Fall in Western Europe. My pet analogy for this moment is somewhere in between the mundane and the dramatic: The Sixteenth Century transition from the Medieval to the Modern eras. Now, as then, the economic, political, social, and religious mind of one age is being shelved and another adopted. Pick your poison, pick your precedent, times they are a-changin’.

The order heretofore is dead. It has been dead for a stretch already. Perhaps the “postmodern” moniker is appropriate to describe what I mean. The Modern world, stretching from the Enlightenment through the end of the Second World War, had run its course. Yet whilst technology developed far apace of everything else, postwar social structures plodded along into the 21st-century largely untouched. What changes there were, were cosmetic. Then came COVID.

A tree is known by its fruit, and this late order of ours has strewn a lot of rotten fruit about. We hear this rottenness, this tiredness, this deadness in milquetoast sermons, we eat it in nutrition-starved foods, we live it in deracinated families, so on and so on in secula seculorum. There’s no end to mediocre examples of this order.

Through its postwar, postmodern facelift we kept the Modern structures going because the mass of us are followers. If we weren’t sheep by nature, then many thousands of hours of industrial education made us sheep. And besides, as Mr. Jefferson reminds us in the Declaration, men are fonder of tolerating evils than of changing them.

Whatever uneasy assurances we told ourselves about this society, we knew they were not true assurances. Admidst the despair and hollowness and commerce of modern life, the better among us did the sensible thing: We became addicts these last 20 and 30 years. It’s only a marvel that more of us haven’t gone in for poisons of whatever sort. When faced with a culture as vapid as the DMV, and Walmart, and the iPhone, one is tempted to grimly conclude with the ancient Greeks that the luckiest man is he who dies in the womb. Who’s the second luckiest man? The one who dies in childhood. And so forth. You get the point.

After a stint in rehab the ones who sober up return to a hell less Dantean and more Quranic, less flashy and more monotonous. Men who’ve come down from their highs this last decade see before them an endless liturgy of bi-weekly pay and once-monthly rent, regular taxes and pointless holidays, forever statues and forever entertainment (always statues and entertainment, always). Nothing of the soul, nothing of the numinous, nothing of life. Indeed nothing but the inane which drove people to the bottle or the needle or the pill or the porn in the first place.

There is no chemical solution to a spiritual problem, so goes an AA maxim. Ah, but musha, the spiritual sorts haven’t been much help. Beyond some local examples of heroism – a religious congregation here, a helpful priest there – the institutional Church has been altogether useless through the late addiction crisis. Nothing so deftly paints the sorry portrait of modern Christianity as the contrast between the long parade of buggery, litigation, and sectarianism of your holy rollers on the one hand, and the robust monthly heroine casualties on the other.

Everything is tired. The Church, the state, art, commerce, you, me.

Yet as we shuffled along intoxicated, or stultified by the mantra, “This is the way the world works,” the center could not hold. Along came COVID-19. Where it came from, how dangerous it is, nor how effective are masks I care not. For the first time in our lives social structures which seemed adamantine have become mice. With Isaiah we ponder, “Are you the ones who shook the earth and made kingdoms tremble?” The entire order which swindled and dispirited and addicted us was put on hold this spring. Soon it will be through.

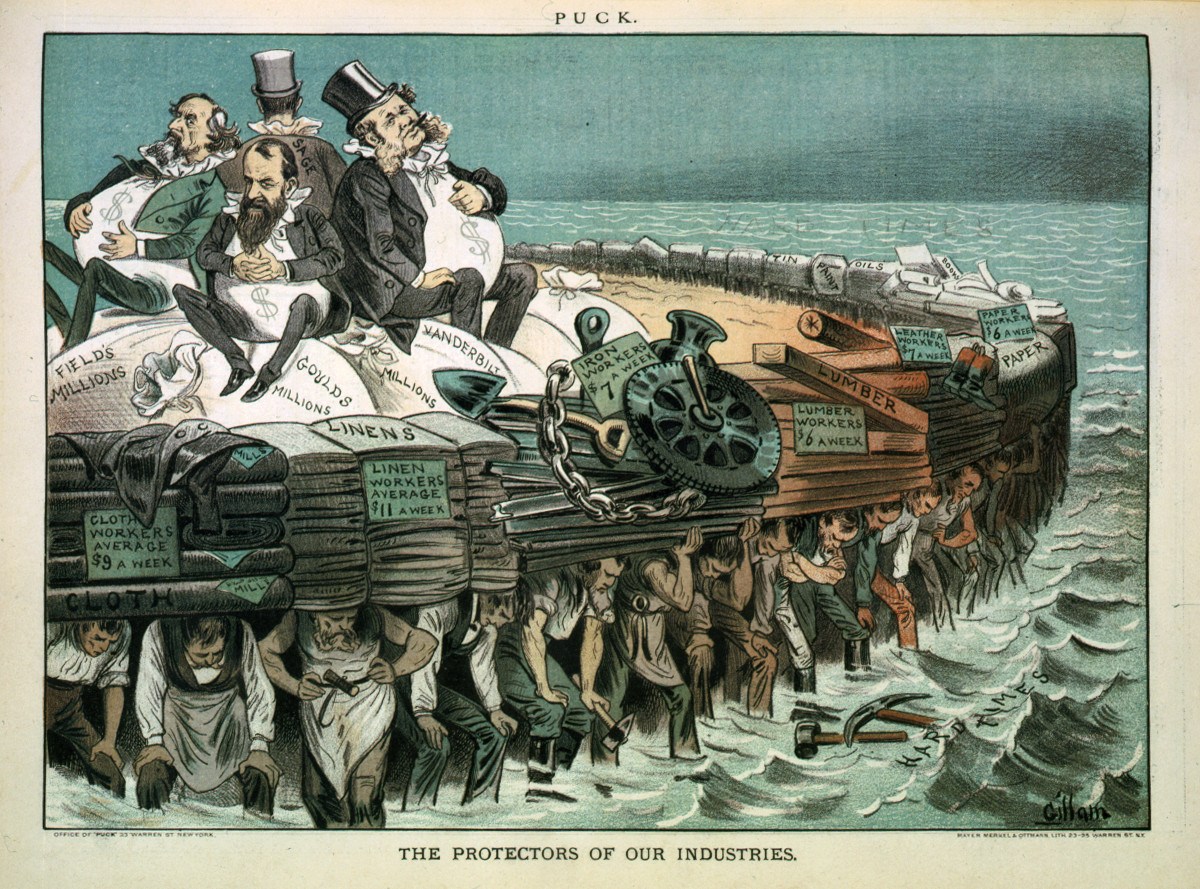

Yet I’m no Pollyanna. Yes, the order was dead before Corona came. Yes, now it is evaporating or soon will be. But a darker timbre is in the offing as the old order, manned by generations of intoxicated or indifferent slaves, continuing only with the force of inertia, crumbles. The powers that be are not as apathetic as they’ve made their servants. They work and they work hard. If things keep apace then surely a technocratic control system of greater personal isolation and crueler economic and legal slavery is in the offing. No man who follows the news is blind to this. A rising secularism, as vicious as it is determined, now verges on leading the mass of Karens and Kevins into a captivity heavier than the one known heretofore.

At this heady moment, at this turning of an age, let us consider youth. It is in the virtues of those years that we may snatch the brand from the fire. Renewed in our minds, we may yet forge a happier epoch.

***

From the word go we note what the remainder of this article is not. This is not the tedious celebration of the vapid qualities of early adulthood which so haunts pop culture. That nostalgia, captured in Bryan Adams’ song “Summer of ‘69” by the refrain, “Those were the best days of my life,” is not what we’re on about here.

There’s a certain fetching style of writing in Church documents which is well worth exploring. You’d not call ecclesial writings beach reading, but they’re not canned either. In a tired Church, “tired” in a way Benedict and Francis and Dante and Chesterton could perceive, one gets the impression that a crew of Lit-majors at some unknown point last century managed to infiltrate Rome. Like a special forces team, I imagine them holding a building, or a floor, maybe just a lonesome closet, of the Vatican complex. There they write their handsome prose.

Communio et Progressio, the 1971 elaboration of the Second Vatican Council’s Inter Mirifica on social communications, recalls some of the beneficial qualities of youth. It says, “Generosity and idealism are admirable qualities in young people, and so are their frankness and sincerity” (67). These are fine sentiments to describe the best qualities of the young. Let’s chew over them, for they are dearly needed in this grey, cant-ridden world.

The opening years of life, years of generosity and idealism and frankness and sincerity, are a chapter of existence which the liturgy especially lauds during the sunny days of summer.

The merry month of June opens with the memory of the Ugandan Martyrs (June 3), and it continues with Anthony of Padua (June 13).

Midsummer itself is crowned with the energy and selflessness of Aloysius Gonzaga (June 21). What’s true for saints’ days in general is especially poignant here. The abstract meets the concrete. Virtue meets flesh. On a day neo-pagans have brought into prominence for the beauty of midsummer’s solar splendor, St. Aloysius’ placement is an annual reminder of Christianity’s sublimation of natural truths. In the youthful Italian’s placement the best of the Classical world and its appreciation for natural beauty meets the Incarnational reality. Pagans are right for celebrating the light of midsummer. In a world of halogen bulbs any nod to the diurnal cycle is welcome. But June 21st is sunnier yet for the memory and intercession of this selfless religious.

Continuing, we see John the Baptist has two summertime days: a bonfire-filled June 24 for his birth, and August 29 for his death. Youth have long involved themselves in protest, and John was given to that type of fire. How fitting, with all the earnestness of a Mario Savio or a Rachel Corrie or a Mohammed Bouazizi, that this cousin of Christ’s would die at the hands of lumpy Herod, a man who’d fallen into the most unappealing of middle-aged habits: the chasing of feckless young women. Enthusiastic Clare, shorn of her teenage locks, graces August 11.

An astute participant in the liturgy will be aware of a small annual drama which unfolds through August’s dog days. Turning our attention to pre-Constantinian Rome, our scene starts with St. Sixtus and his companions (Aug. 7), a crew who’d made the Roman Church famous for its material aid to the indigent. This drama climaxes with martyrdom of Sixtus’ deacon, the earnest and good-natured Lawrence (Aug. 10). In a type of flashback to a generation earlier, our vignette fades out on Aug. 13 with Sts. Pontian and Hippolytus’ sweet after-feast of reconciliation and sacrifice. At the close of their Vespers we turn away from the young Roman Church and we get back on with the regular rhythm and medley of saints’ days.

Things reach a crescendo of sorts with St. Augustine’s Memorial on August 28. Like Clare, who lived a full life, even a long life by Medieval standards, Augustine survived to hoary old age. However, like Clare, it is the saint’s youthful episodes which so endear him in the common imagination.

Let us idle our engines a moment with this beloved North African saint. I will not relate the well-known saga of Augustine’s opening years, nor will I enter into a critique of popular memory’s recollection of the man, a figure whose exaggerated fleshly vices get more play than they deserve. His very real intellectual difficulties are less spicy.

The ability of a subject to inspire art is a sign towards its truth. The beauty argument doesn’t win the day in se. I can think of a young New York artist, for example, who regularly lends her considerable talents to Planned Parenthood sorts. Foul things can be dressed up beautifully. Sed nihilominus, as a general rule on an average day, the statement stands: Beauty points towards truth. Thus I adduce Bob Dylan’s I Dreamed I Saw St. Augustine as a concluding aid in our meditation on the virtues of youth. It begins,

I dreamed I saw St. Augustine

Alive as you or me

Tearing through these quarters

In the utmost misery.

The tune of this song follows an old I.W.W. ballad about labor organizer Joe Hill. The martyred Wobbly left a large corpus of music. Its poetic quality is impressive for someone who learned English as an adult. Like Hill’s postmortem legacy, Augustine’s personality transcends time and translation.

In books like The Confessions his moral and mental struggles are ours. Augustine’s Civitas Dei confronts questions of political philosophy which press upon the latest headlines. Tearing through these quarters indeed! And whilst contemporary patois limits “angst” to teens at Hot Topic, Dylan’s imagery of a vital, confused Augustine running through our song is excellent for its relatability.

With a blanket underneath his arm

And a coat of solid gold

Searching for the very souls

Who already have been sold.

The already sold souls is as true a line as anything ever written. By war and pharmaceuticals and jobberism, by a thousand stratagems, the tired world plots to turn the rising generation into itself. Very often it works towards this end unbeknownst to itself. And in this we get a whiff of the magnitude of Original Sin.

Those already sold souls weigh heavily for Americans. Twice now gombeen-men have wrecked the careers and savings of Generation X with their recessions. The flashy endless wars which opened the century have morphed into a regular simmer of unreported conflicts. But flashy or quiet, here in holy Connecticut I oft’ come across scarred young men of a certain age. That betrayal of youth is more visible and sympathetic than the debt slave graduate who embraces a future equally as indefinite as our wounded soldier. Sold all, they are.

Perhaps Augustine’s blanket in the above stanza is a nod to the popular overplay of his lust. If so, we hear our young genius rushing out of his girlfriend’s pad shouting,

Arise, arise, he cried so loud

In a voice without restraint

Come out, ye gifted kings and queens

And hear my sad complaint.

A certain aspect of my educational work rings especially clear in this verse. Regularly I have the opportunity to interact with young men and women lately through with college. As it happens, usually because I’m trying to lasso them for a speaking gig or to teach a class; they have a humanities background. There’s something especially forlorn about this condition. Being in your twenties, having come to the end of the education-conveyor-belt, and being adrift in a STEM-world with a liberal education. The general adriftness of that hour of life is compounded by suddenly going from a world of letters and ideas to a society illiterate and apathetic. In this tribulation some encouragement is always welcome, you gifted kings and queens.

As the stanza ends, we wonder what complaint St. Augustine has? We find out:

No martyr is among ye now

Whom you can call your own

So go on your way accordingly

But know you’re not alone.

“No martyr is among you now.” Who knows how much Bob Dylan studies the Church Fathers? Whatever the case may be, this verse captures an anxiety Bishop Augustine explicitly commented on in his day. Living in a time and place when Christianity was going from being on the margins of society to being socially acceptable, including a cessation of state-sponsored persecutions, there in fact was a belief that the days of martyrs were through. In the Office of Readings on Laurence’s day (Aug. 11) Augustine preaches the second lesson, saying, “It is not true that the bridge was broken after the martyrs crossed; nor is it true that after they had drunk from it, the fountain of eternal life dried up.”

Dylan’s Augustine expresses how we can often feel. In a half-hearted world it seems there are no martyrs anymore, no one who’s so committed to an idea they’d die for. “Where is our James Connelly?” another Wobbly writer once asked. Yes, but where are our martyrs? They’re out there. Like the previous sections, this one closes with encouragement.

***

What agendas are moving now and where they are going is stuff for another article. Those with eyes to see know what’s up. Still and all, before we fill up those seeing eyes of ours with intimidating thoughts of this rising order, let us remember youth and the saints who embody those qualities of generosity and frankness and idealism and sincerity.

In the best tradition of Christianity, we also remember that just as Israel and Edom are ultimately spiritual realities, so is age and youth. Brigitta in Graham Greene’s Power and the Glory is used as a negative reminder of this. Kids can be washed-out cynics as soon as anyone else. On the positive end, though, even wrinkly old priests can say with all the newness grace brings, “I will go to the altar of God: to God who giveth joy to my youth.”

John Coleman co-hosts Christian History & Ideas, and is the founder of Apocatastasis: An Institute for the Humanities, an alternative college and high school in New Milford, Connecticut (USA). Apocatastasis is a school focused on studying the Western humanities in an integrated fashion, while at the same time adjusting to the changing educational field. Information about the college can be found at its website.

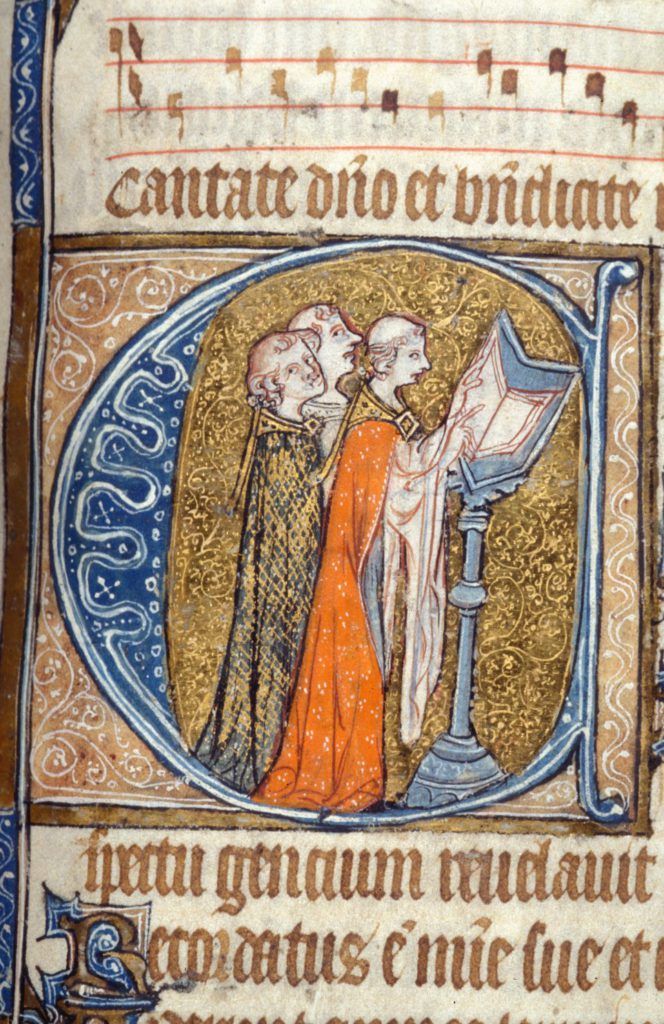

The image shows, “the Conversion of Saint Augustine,” by Fra Abgelico, painted ca. 1430-1435.