Origin

The September issue of the Postil, contained an interesting article by Valentin Fontane Moret about Ernst von Salomon, seen as a revolutionary, a conservative, a lover. By chance just that month I published in Italy a book about the withdrawal of the Freikorps from the Baltic, and that article made a small bell ring in my head. Thus, I’d like to underline some aspects related to those facts. It could be useful in order to get a better focus on von Salomon and his environment in 1919, because those facts are often perceived as a sort of clash between Right and Left, between Europe and Communism; and, anyway they are the facts which make of him both a revolutionary, and somehow a conservative, if he was a conservative, of course.

The first point I’d like to discuss is a statement by Fontane Moret: “Dominique Venner was able to describe this mythical epic as a nihilistic adventure.” Was it really so? I mean, to von Salomon it was surely an epic adventure, but in itself, by itself, was it so? And was it nihilistic?

There are some aspects we must take in consideration. The history of the German occupation of the Baltic Eastern coast is not so well known beyond the Baltic countries. In the general mind it relies upon, or better, it is heavily affected by, Venner’s book Baltikum. Venner in fact depicted the German occupation as a mythical epic, and rendered it familiar to an entire generation of Right-winged young men, the Western European generation of the late 1970’s. As a result, a wrong perception of those old actions arose among that youth, and the young men of 1978 thought of those German fighters as heroes desperately fighting for German and European traditional values against the mounting barbaric, blindly violent wave of the Slavic threat from East.

A first point needs to be underlined here—in von Salomon’s mind, the difference is between the men and—literally, I quote him—the “white negroes.” These two words used by von Salomon in person when in his book Die Geächtenen—The Outlaws—he spoke of his further commitment in Upper Silesia with his comrades. They went there to defend German civilization threatened by a plebiscite to decide if the region had to remain German or pass to Poland; and he tells the reader that he, and his comrades agreed with the British privates in despising the soldiers of the other peacekeeping forces – French and Italians in that case (hence, as an Italian, I’m included, and I wonder whether Venner realized that, as a Frenchman, he too was included)—looking at them as at racially inferiors. Basically this was the same mind von Salomon applied to the Balts, and to the non Germans he and his comrades fought against in the Baltic; only, he depicted them as merciless barbarians.

Second point: how long did that mythical epic last? Not that long, actually. The first Freikorps were established in early 1919, and reached the Baltic area in March. The last left Lithuania by December 13th that same year 1919; hence in the very longest case, they remained in the Baltic countries eight months and half. This, of course, can be enough to build a myth, and to generate a mythical epic, for there is no rule about how long an enterprise must be to became mythical and epical.

But was it really so? I mean, this was von Salomon’s perception, or, at least, the way he later portrayed it. But did the other fighters really share von Salomon’s vision, or not? Who were they? The answer is not easy.

The Myth and the Reality

There was no standard of the German fighter in the Baltic. There were all kinds of people. It is true that many of them later joined the Nazi Party, but—warning—to be a Baltic veteran did not mean that one became a Nazi later, because many veterans simply did not join the Party. For instance, Gotthard Sachsenberg, a pilot and one of the best-known officers of the Freikorps, never joined the Nazis and had a lot of troubles from 1933 till 1945. Moreover, it is wrong to think that whoever was a German conservative later joined the Nazis, because—what is normally forgotten—Nazism was a leftist ideology, just like Fascism in Italy, whose roots lay in Socialism.

In the 1930’s, Nazi propaganda emphasized the Freikorps, and underlined their will to fight against the barbarians; but if we look carefully at the entirety of the fighters, the fight against the barbarians did not cover everybody’s reasons. To be complicated, these probably were some of the reasons of some leaders, and some soldiers, but surely these reasons were not shared by all the combatants.

For example, we rarely have only one reason to do something. Normally we are pushed by different aspects, some of them may be more relevant than others, but rarely, or never, do we act because of one reason only. The same happened to the members of the Freikorps. Because of various studies, we know who they were, and what did they thought, after von Salomon in person, who on page 67 of the Italian first edition in 1943, wrote: “There were in the Baltic, many companies, regulated corps under self-confident leaders, regularly enlisted, who marched obeying severe orders; hordes of restless adventurers who looked for war, booty and disorder; patriotic corps who did not resign to the ruin of the motherland and came to defend the borders against the breaking-in red torrent.

There was also the Baltic Landwehr, enrolled by the nobles of that region, willing to save at any cost their seven centuries of tradition, their consistent, refined culture and the Eastern bastion of German lordship; there were German battalions composed of peasants who wanted to colonize: they were ground-hungry, they sniffed the earth, calculating the resources which could be offered by that harsh soil. But troops ready to fight for the order, there were none. The great number of words gave everybody the certainty that they too would receive a minimum of reward and hope, an attractive goal.”

So, there were idealists, there were outlaws, there were people who did not like to go back to the civil daily life based on a monotonous and hard work, and there were the poor men, who, when civilians, were fatigued from dawn to the evening, and could hardly survive. How many were there of the latter? Which ratio they were in the total?

Von Salomon just told us: “There were… companies…. who marched obeying severe orders; hordes of restless adventurers… battalions composed of peasants who wanted to colonize.” A horde can be big or small, but normally is not that big; a company is smaller than a battalion—normally you need from four up to six companies to compose a battalion—and if the “disciplined” soldiers, let us say the idealists, composed companies, the peasants composed battalions, hence the peasants were the absolute majority. Why?

The situation in Eastern Prussia, being Eastern Prussia it was the most similar area to the Baltic countries due to history, geography, economy and, above all, due its landlords and their estates.

In the last quarter of 19th century, agriculture in Eastern Prussia was less and less convenient. Bismarck did his own best to support agriculture. He increased and made easier to get State credits, and kept high taxes on foreign products, especially on wheat and corn, to protect Prussian agricultural economy.

The situation balanced, but, in the last years of the century, agriculture became less and less profitable, and many landlords preferred to sell their estates, and reinvest the money in the financial market or in industry. On the other hand, many workers abandoned the countryside, and moved to cities, looking for a factory job. The life conditions of the lower classes were so bad that more than five and a half million Germans emigrated to North America between 1820 and 1920, with a yearly maximum of 250,000 in 1882, not to speak of those who went to South America or to Africa.

Basically, by the end of 19th century, a great Prussian landlord often spent for his farms more money than he got from them. On the other hand, getting a small property was seen by the lowest class as a way to escape poverty, but a way prevented by an obstacle—the money needed to purchase the land.

In 1890 Bismarck resigned. This opened the way to the supporters of free market, and to industrialists. The new chancellor von Caprivi ended protectionism, and agriculture was heavily affected.

By the end of World War, I big Prussian and Baltic landlords perceived their land properties as a source of troubles. It was possible to live exploiting them, but if one could sell them for a good price—especially in a period when cash was scarce—and if in the Baltics one could keep properties or sell them without being killed by the incoming Bolsheviks, that would be best of outcomes.

On the other hand, small farms could give poor families a better life, especially during the post-war crisis; and that’s why the Freikorps were filled with people attracted by the promise to get lands in the Baltics.

True or not, the Freikorps soldiers knew that when the Letts lost Riga, and Mitau, their troops would oppose the Bolsheviks, thanks to German help, holding a weak line around Windau, as von Salomon wrote later: “Ulmanis’ Latvian government escaped from Riga to Libau, and nonetheless promised land to be colonized to the German volunteers: eighty morgens of land, relevant credits and a better wage if they re-conquered those cities.”

A Morgen—a morning—was the land one could work in half a working day; more exactly it was two third of a Tagwerk—the “work of one day”—and, besides of all the kinds of Tagwerk existing in history along the Baltic coast, in 1869 the Northern German Confederation stated it to be 2,500 square meters, and if including Prussia with the Baltics, it could be up to 2,700; hence 80 Morgens meant a no less than 20 hectares—or 60 acres—land to each veteran; that is to say, not too bad a bad farm, for free.

Because of that promise the Freikorps fought; because of that promise they re-conquered Riga and Mitau; because of that promise further volunteers engaged in one of the 16 recruiting centers scattered everywhere in Germany, and came to the Baltic as reinforcements; because of that promise they were the tools used by Winnig to try to achieve his plans.

Winnig was a high-ranking Reich official, the Superior President,\; that is to say the governor of Prussia. He was a Social-Democrat and had a plan in mind. Just to make a long story short, basically he wanted to organize a German State separated from Germany, including Prussia and the Baltic countries, in order to keep German values alive there. He thought that if none of the new countries born after World War I had been regarded by the Allies as co-responsible for what Germany and Austria-Hungary had done, the same could probably be applied to a new German State, which was not the German Reich. No matter how unlikely this plan was, at that time the Baltic barons, who were linked to German culture, and were the landlords especially in Latvia and Lithuania, found the plan interesting; as well, the highest ranks of the German Army in the Baltic also found the plan interesting. So, in Spring and Summer 1919, German regular troops, enhanced by the incoming Freikorps, helped to expel the Bolsheviks, to save the interests and properties of the Baltic barons and to achieve the Winnig plan.

At the beginning, the Allies in Paris had so many troubles everywhere that if the Germans kept the Reds off the Baltic, it was fine. But then, in early Summer 1919, they realized how many well-armed German soldiers were there—50,000, that is to say half of the German Army as foreseen by the Peace Treaty—and decided it was better to recall them; and because they were still holding some territories that Germany had no right to claim, unless they held on these territories until the day the Versailles Treaty would be ratified.

The German War Minister Noske was asked by the Allies to call the regulars back to Germany, and he did. But the more the regulars left, the less the volunteers accepted to leave. Why? Because to most of them the core of the question was the land they expected to get, and how they could get it if they went back to Germany?

By the way, in the harsh days of the German revolution in winter 1918-19, Noske relied heavily on the Freikorps. But when the revolution was over, he did not know what to do with all those armed men, who, being war veterans, knew quite well how to fight. Having no idea, in early Spring 1919, he was happy to silently allow them to proceed to the Baltics, where Winnig—belonging to his same party—was furthering his plan. And all went well till the Allies also demanded the volunteers be recalled, and Noske had no other option. He tried to recall them, but the reaction was quite bad. On August 24th, 1919—according to von Salomon’s account—Josef Bischoff, commanding the Iron Division (a lieutenant colonel from the reserves)—appeared at the Mitau station, and, in the general confusion, prevented the departure of the first train carrying the 1st Courland Infantry Regiment back to Germany.

Then Bischoff came to an agreement with the White Russian units in Lithuania, and his men now served came under General Bermondt-Avalov’s Tsarist colors. But a problem remained—who would pay for needs of the Iron Division? Their supplies, wages and so on? And who would pay for the other Freikorps?

By September the Letts and the Lithuanians were trying to eject the Germans from their countries who did not want to leave because they were collecting the harvest and sending ut to Germany—a way to survive through commerce—and they were also getting horses, and food. In Latvia the Germans were still before Riga, and kept Lithuania which, being between Latvia in the north and Prussia in the south, was vital to get military supplies and ordnance from Prussia.

Clashes against the Germans occurred in Latvia and Lithuania; and the whole population—supported by the British—was against the Freikorps. Why? Because no matter what one may now think, the German speaking population in the whole of the three Baltic countries (Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania) hardly totaled 10 percent. And what about the “Germanic” culture, the Germanic soil and so on? Well, the landlords, the Baltic barons, the civil officials, they all shared a certain German flavored culture. They spoke German—and Russian, and the local language, whatever it was—no matter if those lands had been part of the Russian empire, and if many of them had served the Czar against the Germans in the just ended World War. So, what von Salomon implicitly admitted when mentioning the “bastion of German lordship,” and did not explicitly say in his work, was that he and his comrades were fighting on non-German soil, and against the population that soil belonged to, just and only to keep the interests of the small German speaking minority, composed of the landlords, and of the Baltic barons, and just to get the 60 acre farms each soldier had been promised by the Letts, if they ejected the Reds, and that was it.

There is not that much myth in this, I’m afraid—besides the artificial myth built by von Salomon who, probably, believed honestly the stories they told him, and refused the rational result of what his eyes saw, and his ears heard: people did not speak German there, and that was not a German land, no matter if the German knights had built Memel castle in 15th century. It was not Germany and it had never been Germany.

The Epic and the Reality

On November 12th, 1919 a group of five Allied officers entered the castle of Koenigsberg, the capital of Prussia, to meet Winnig and the local military commander, General von Estorff.

The Allied officers composed the Interallied Commission for the German evacuation from the Baltic countries, and their task was to let all the Germans go home, not only the regulars—all, Freikorps included. The Commission was chaired by a French division general, and included an American, a British, and an Italian brigadier, and a Japanese major. Before long, they got Winnig to realize that his plan was over—no German military could remain in the Baltics; and that meant the end of the dream of a Germanic state which was not Germany.

It would be long and boring to explain how the Commission succeeded and achieved its task. What is important is that by November 28th the evacuation of the Germans belonging to the Freikorps began, and was hurried by a Latvian offensive—mentioned by von Salomon—pushing them from Southern Latvia into Lithuania.

There were fights, of course, between the Letts and the German rearguards. And, before retreating, the Germans damaged as much as they could, and stole as much as they could, as the Commission then recorded. The Latvian government later presented a bill, listing a 283 million Reichsmarks total damage, and Noske, and the Imperial Chancellor Bauer were notified of the huge amount of damages that Germany had to pay back to Latvia and Lithuania.

The Commission enforced the end of the fight. In a few days they obtained a cease-fire by the Letts, Then they convinced the Lithuanians to not engage the Germans further; otherwise, they explained, how would it be possible to get them to leave?

So, by December 4, 1919 no further action was carried out, and the Germans were free to leave. As one can see, up till this point the epic combat lasted six days, and it seems not to have caused huge casualties on both the sides. There were casualties, of course, but a few, because the Commission asked both the Latvian and the Lithuanian government not to further engage the Germans, to avoid any pretext the German headquarter in Prussia could exploit to send reinforcements. The Commission was obeyed; the fights ceased, and the Germans left.

In that moment they were more or less around the small Lithuanian city of Siauliai, a railway hub, 123 kilometers south of Riga, and that was the longest distance the Freikorps marched along, and sometimes fighting—123 kilometers and no more.

One may wonder, how is it possible that if the Freikorps Rossbach is remembered for its glorious 1,200 kilometers march from Thorensberg, now known as Torņakalns, a suburb of Riga—to Berlin? Good question. But during their withdrawal, as soon as they reached the safe zone protected by the cease-fire, they were embarked on trains, and went back to Prussia—that is to say to Germany—by train. Hence, they marched only a bit more than 120 kilometers, and then they made a 1,080 kilometers trip, almost all in the German homeland, and mostly on the German railways to Berlin. Free. So, it is true that they marched from Riga; it is true that they went to Berlin; it is true that the distance between these two cities is 1,200 kilometres (actually the shortest is 1,044, but no matter: they did not go via the shortest route). But I’d say that later the data was a bit worked on to make it sound more epic. The Iron Division refused to use trains, and marched from Siauliai to the Prussian border—134 kilometres. But after leaving Siauliai on December 4th, they faced no threat and were never engaged in a fight.

Can we consider a trip by train epic? Perhaps, if there are some unexpected facts—e.g., as happened in the Far-West—yes, but unfortunately that trip happened without any inconvenience, not to speak of fighting, and with all the precision Whilelmine Germany was famous for; hence no delay, no incidents; regular trip at regular speed; not that epic, and very middle-class style, I’d say.

Comments

At this point, one should wonder if that adventure was really nihilistic as depicted by Venner, not to speak of the myth, and of the epic; and it will be useful, I’d say, to underline some aspects.

The first is how dangerous it is to rely on myths instead of on history; not on stories; on history; that is to say on facts. As you have seen, facts were a bit different from the way the story was later told.

A second aspect is how dangerous the myth is, because it misleads a lot of people. I do not know how much Baltikum was responsible for the errors made by many who were young when I was young, but I know for sure that it gave them a distorted vision of some facts, which it would have been better not to emphasize.

There is a problem here, a problem born of the misperception of Nazism, purposely seen only as a sort of somehow conservative ideology, aimed at keeping Western civilization (carefully not mentioning some small details as the Nuremberg laws and their consequences), and engaged in a mortal clash against Barbary and the dark forces—the Communists—who wanted to destroy the civilized world and its values. Well, it was not so; it never was so. In short, Nazism was not conservative. It attracted the German conservatives; it involved them; but it did it so only to destroy them and their potential opposition. Nazism and Communism were basically the Hegelian Right and Left; thus, two arms of the same creature. Thus what difference could there be between the two?

But this misperception (among other things) of looking at the German campaigns in Russia since 1941 as at the fight of the Western values against the Barbarian East was—and is—misleading, and wrong on may counts. It’s wrong because it is based on racial difference; hence it puts among the barbarians all the Slavs—including a highly civilized, and cultured people like the Poles, a real pillar of the West, always. It’s wrong because it focused exclusively on the Germans as the only keepers, and protectors of the Western civilization, which, with all due respect to Germany, is not right. It is wrong because it misled, and still misleads, thousands, tens of thousands young people in Europe, and out of Europe toward those wrong opinions, letting those people happily pass over a not so negligible fact—had the Nazis won, a huge ratio of those young Nazi supporters would have been considered as subhuman, because they do not belong to the German race, and it is not enough to feel pro-Nazi to be accepted by the Nazis. One is accepted in a group not because he or she feels alike, but is accepted because the members of the group assess his or her standards, and decide whether these standards suit their own standards or not. And, being the standard in this case only a racial one… you may realize the result.

Last, and worst, the narrative of the Freikorps in the Baltics was deprived of its actual aspects; thus no Winnig plan, no quest for a farm, and for a quiet family life, but a heroic clash, artificially and purposely built, in order to create the root of a political myth, to be exploited later by the Nazis as a heritage, and a legacy. And, grounding on that heritage and on that legacy, we have seen the Nazis doing terrible things.

So, I wonder, shouldn’t we stop considering von Salomon, his book, and Venner’s Baltikum as part of conservatism and its values?

Ciro Paoletti, a prominent Italian historian of military history, is the Secretary General of the Italian Commission of Military History. He is the author of 25 books, and more than 400 other smaller works\, published in Italy and abroad, and mostly dealing with modern and contemporary Italian military history and policy.

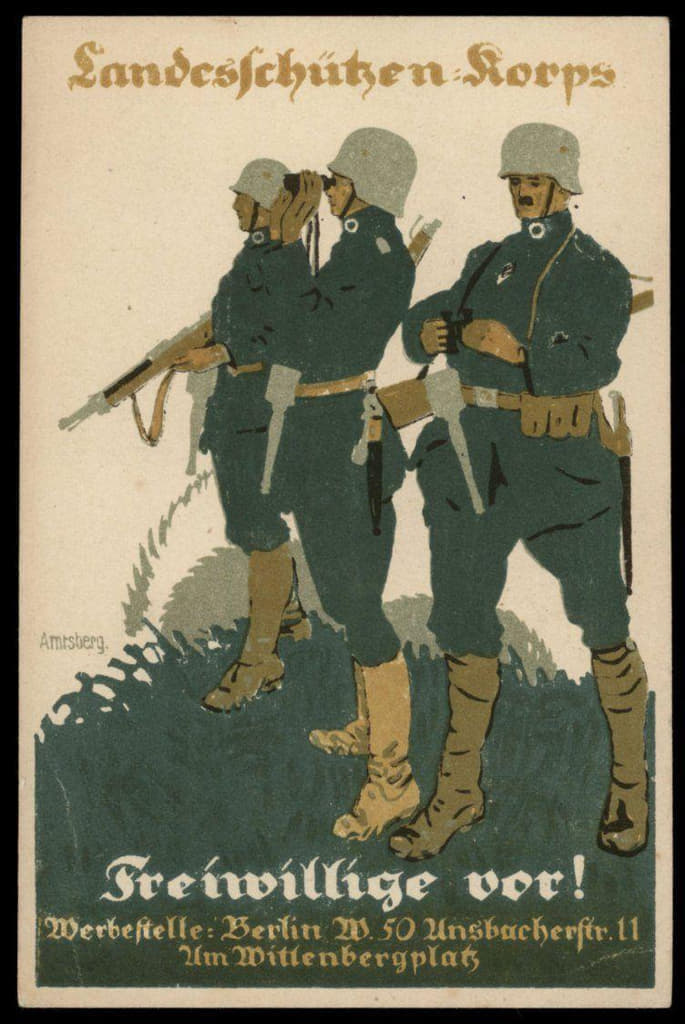

Featured: Freikorps Berlin Landeschutzenkorps Recruiting Card, 1919.