If journalist Patrik Baab had spoken of Germans’ “escalation phobia,” he might still be doing his teaching job at Kiel University today. However, he was doing journalism: That is the worst reproach one can face today.

Journalists who have more than just attitude, namely professional ethics, are having a hard time these days. A current example: Seymour Hersh. Using an anonymous source, the American journalist has worked out who is to be held responsible for the attacks on Nord Stream I and II—namely, the US Navy and Norway. The German press pounced on this eminence of American investigative journalism, making the man look like a novice. The criticism came from “colleagues,” journalists who spend most of their working lives sitting at desks or copying from each other.

They are rather unfamiliar with field studies. For them, journalistic work simply means accepting prefabricated opinions, only questioning them when instructed to do so. When the U.S. government denied Hersh’s report, these critics of Hersh accepted the denial as a credible opinion—here their journalistic intuition once again ended abruptly.

Much like Hersh, German journalist Patrik Baab has fared similarly in the recent past. He left his desk to do something that contemporary journalism in Germany hardly ever does anymore—get an impression on the ground. In the end, that is exactly what he is accused of. As a journalist, it is apparently advisable in these times and lands, to remain dutifully seated in front of one’s laptop and do research on Wikipedia and in the vastness of Twitter. But never in eastern Ukraine.

Baab in Eastern Ukraine

NDR journalist Patrik Baab was on the road in eastern Ukraine last September. The reason for his trip there—research for a book project. For him, taking a close look at conditions on the ground is part of the journalistic standard, as he also points out in his book Recherchieren. Ein Werkzeugkasten zur Kritik der herrschenden Meinung [Research: A Toolbox for the Critique of Prevailing Opinion]. At that time, those controversial referendums were taking place in Luhansk, Donetsk and Kherson, which were supposed to allow the regions to join the Russian Federation. Baab was present. He observed the events on the ground as a journalist—but not, as he was subsequently accused, as an election observer.

Usually, election observers are appointed or invited. Patrik Baab never received such an invitation; to a certain extent, he was there on his own behalf. As a researcher and curious journalist. Nevertheless, the reaction followed promptly: A report by Lars Wienand for the news portal of t-online drew attention to the fact that an NDR reporter—Baab—was acting as an election observer at those referendums and thus legitimizing Russia’s controversial approach.

In other words, a journalist was reproached for doing his job. If the mere presence of a journalist at critical events led to the legitimization of these events, then—viewed dialectically—reporting in the true sense would no longer be conceivable. Because the journalist would already be an influencing factor qua existence, who could no longer act as a chronicler of events, but would only change events through his presence. Perhaps this is the reason why on-site research is becoming increasingly rare today—because they want to stay out of it—which would be tantamount to an oath of revelation for the profession.

Decision, After a Few Minutes

Baab was promptly accused of having aligned himself with Putin’s cause. His visit to eastern Ukraine was proof of that. Patrik Baab himself distances himself from Russia’s war against Ukraine. His CV as an NDR reporter includes countless films and features that report critically about and from Russia—and thus do not make the Russian leadership look good. Infosperber has linked to some of Baab’s productions under an article on the case: They prove that the journalist always kept a sober distance in regards to Russia—professionally speaking.

Although the accusation that Patrik Baab was present as an election observer cannot be verified (here, election observers have their say, Baab was not present and also not invited), the Hochschule für Medien, Kommunikation und Wirtschaft (HMKW) in Berlin distanced itself from Baab. In the past, the journalist had often worked there as a lecturer. Among other things, the HMKW’s justification stated that Baab was “providing a welcome fig leaf for the aggressors.” In addition, he was engaging in “journalistic sham objectivity”—the HMKW statement can be read here. Interesting is the introduction of the justification report, in which they speaks of having learned of the matter only “a few minutes ago, through the article, Scheinreferendum, hurra, by Lars Wienand (t-online.de)”—after minutes they had already decided? That doesn’t sound like a prudent approach, more like a favorable moment for people who want to make a political example.

Since Patrik Baab did not have a valid contract with HMKW, he could not take action against this decision of a few minutes. In the case of the Christian-Albrechts-University in Kiel (CAU), the situation is somewhat different. It withdrew his teaching contract one week after HMKW. The reason—factually the same. Apparently, they didn’t even bother to contact Baab in advance. The reason given by CAU was that there was “imminent danger.” One puzzles over what this is supposed to mean: Baab was standing with tanks in front of Kiel—that’s not possible, because the tanks heading for Ukraine are not in front of Kiel, they are in Kiel.

In this matter an appeal is now pending, the “revocation of the teaching activity” seems to be unfounded for many reasons. Baab was not an election observer, he was doing his job: CAU has demonstrated a lack of due diligence in checking press reports on Baab’s trip. It has done exactly what Baab, as a journalist, urgently warns against—it has adopted unverified allegations.

Kiel University: Followers, by Tradition—and More

Without going into the historical misdeeds of CAU in depth, Kiel University has a tradition of having a rather divided relationship to democratic standards—to put it kindly. In 1914, for example, it excelled in jingoistic patriotism, and years later it supported the Kapp Putsch with a Freikorps (the author Axel Eggebrecht gave a very vivid account of this in his book, Der halbe Weg. Zwischenbilanz einer Epoche), and not only did not stand aside in 1933, but clearly encouraged professors to support the new rulers. Moreover, the author Katia H. Backhaus, in her work, Zwei Professoren, zwei Ansätze. Die Kieler Politikwissenschaft auf dem Weg zum Pluralismus (1971—1998) [Two Professors, Two Approaches. Kiel Political Science on the Way to Pluralism (1971—1998)], elaborated that CAU faculty worked closely with intelligence services (with German and also American ones) in the 1980s.

This historical dimension of CAU will be addressed separately in the near future, as it deserves further consideration. It should be remembered, however, that a professor by the name of Joachim Krause from the Institute for Security Policy at the University of Kiel recently attracted attention. He recently called for escalation and spoke of an “escalation phobia” in large parts of the German population. Krause has admittedly not even been reprimanded by CAU. In retrospect, there would be at least one more reason to do so.

Twenty years ago, Krause justified the war of aggression by the United States and the British against Iraq, which violated international law. Krause’s 2003 analysis bears eloquent witness; it can be read here. In the concluding remarks, one reads “that the U.S. policy toward Iraq (including the threat of regime change by force) is extraordinarily consistent with the international order of collective security and is also necessary.” And further: “The primary motive of U.S. policy is to put a state in its place that challenges the current international order like no other.” Obviously Krause let himself be influenced with this statement by those hawks of U.S. policy who at that time were already talking about weapons of mass destruction in Iraq and whose insistence resulted in that lying appearance of Colin Powell before the UN Security Council.

War of Aggression by the USA: No Selfish Energy Interests

Critics, who even then spoke of an unlegitimized war of aggression, were immediately rebuffed by Krause. He wrote: “There is no evidence to support the assumption that U.S. policy is primarily guided by selfish energy interests.” The French and Russians, however, are different, being oriented “by very narrowly defined financial interests in oil exploration in Iraq.” The U.S. foreign policy, so Krause explained at that time quite unabashedly, acts for reasons of good intentions—just imagine if someone would want to accuse Putin or Russia in general of that today.

CAU accuses Patrik Baab of not doing his journalistic work properly because he is biased—at least, that is the quintessence that one has to come to, if one takes a look at the reasoning. But an academic who works in security policy and at the same time talks about “escalation phobia”: How does that go together? Is that the choice of words of someone who specializes in security policy issues? Why does Krause not accuse anyone of failing in their task?

If Patrik Baab had spoken of escalating the war to the point of a potential nuclear strike, he would be blithely lecturing in Kiel today. His offense was that he did not allow himself to be turned into an academic utility idiot, but pursued his work ethos—he does not postulate any ideological empty words, but does what he knows how to do: Reporting.

Basically, this seems to be—as already touched upon above—the worst accusation that one can currently be confronted with. For quite some time, journalism has been understood as something that constructively accompanies the structures of power. It is not implemented as a corrective, but rather takes up the banner of guiding politics through everyday life. If possible, without causing too much of a stir. Synonymous with this development are the legions of journalists who serve as so-called fact checkers. Their task is not to bring facts to light, but to create facts that support and back up political guidelines or decisions. By definition, the fact check should be open-ended: However, if you start with an intention, there can be no drawing back; rather, everything is already closed off and fenced in.

Real Journalism: Endangering the Way Things are Going

Journalists like Patrik Baab come from a different time, when it was still considered natural to even sometimes antagonize the powerful or even just one’s own editor. Of course, journalists are narcissistic, a fact that Patrik Baab himself confirms in his book mentioned above: They always want—and wanted—to make a big deal about themselves. In other days, this was achieved by an investigative coup, by a piece of information that was difficult to bring to light and that could be presented. Today, you make a splash by supporting narratives that business and politics want to establish. In this new sense, Baab is admittedly a bad journalist—precisely because he is a good journalist.

Some students at Kiel University have also recognized this. They are demanding justice for Baab. Their statement on a small Telegram channel about the “Baab Affair” [Affäre Baab] reads” “Comprehensive research that illuminates all angles is a journalistic quality characteristic and not a moral crime. We therefore demand Patrik Baab’s immediate reinstatement at CAU.” Julian Hett, initiator of the burgeoning resistance against CAU’s actions also told me: “The t-online article gave false factual claims, which have since been corrected. Thus, it was clear for me: reputation before truth! The last three years of Covid politics at the university have already shown me in which direction the whole thing is developing. Therefore, there is an urgent need for reforms that put truth back in the center and allow debates, even if they are controversial. Instead, however, efforts are being made to introduce gender language in an all-encompassing way.”

The Baab case shows that journalism is an offense these days. But only if it is carried out with all due diligence. Those who play journalism from their desks because they are halfway capable of comprehending dpa reports are sitting on the safe side of a profession that is in the process of finally abolishing itself. To prevent this, it is imperative that the expertise of a man like Baab not be lost. He should not be one of the last of his kind—he still has a lot to show many young people whose dream job is journalism. To stop letting him teach ultimately means losing his expertise. Only people who see journalism as court-reporting can want that: And these are the forces of counter-enlightenment.

Roberto J. De Lapuente is a journalist who writes from Germany. He is the author of Rechts gewinnt, weil Links versagt [The Right Wins because the Left Fails]. This article appears through the kind courtesy of neulandrebellen.

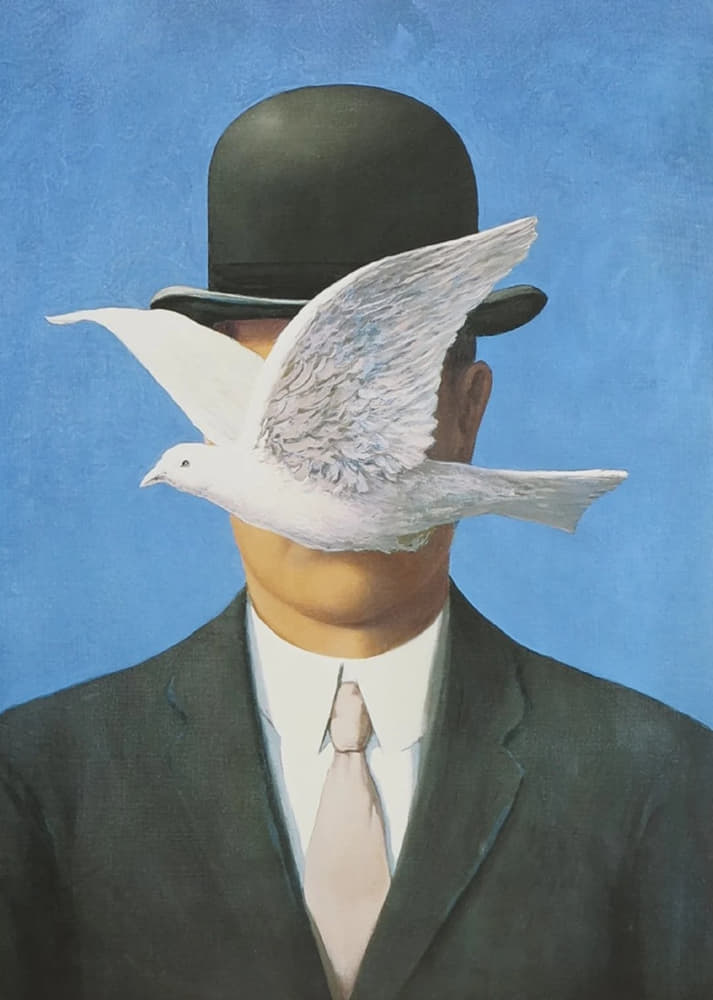

Featured: Man in a Bowler Hat, by Rene Magritte; painted in 1964.