My dog—our dog, my wife’s and mine, although he is more hers than mine—besides being a dog has the misfortune of being called Claudio (and hereinafter Claudio). As I was saying, Claudio spends about seventeen or eighteen hours a day in a lethargic state, something normal in animals of his species, and he also dreams. We know this because from time to time he starts barking in his sleep, throwing urgent but muffled, half-drowned and rather high-pitched barks while slightly moving his front legs as if he were galloping or defending himself from dreamlike enemies. Then he wakes up and the bad time passes.

What is reasonable, I think, is to think that Claudio, in his psychological, mental and cerebral condition of a canine entity, does not distinguish the world of dreams from the realm of the real; for him, passing from dream to wakefulness is an inconsequential shift, like a blink of an eye or something, without further break in the only category of the factual perceptible that he knows and distinguishes. In fact, for him, as for many people, the perception of the environment supposes everything, it is integrated into his vital experience without distinctions of rank established by situational opposition; in short, what is dreamed is as real as what is lived; what is felt and integrated into his world of sapiential references during sleep is as important as the same elements developed in the waking state. This leads to two conclusions that I find disturbing. The first one: my wife and I are a small and non-determining part of Claudio’s life; and the second one: his main nucleus of knowledge is based on the improbable and vague sphere of dreaming. Thus, I can conclude and I conclude by affirming that the good Claudio, in his transit through the real shores of existence, lives a life founded on false learning, illusory experiences and misplaced knowledge. In spite of which he loves us very much, something to be thankful for.

Naturally, if we transfer these observations to human behavior, we will reach identical conclusions. We leave aside, of course, the descriptive erudition of those anthropologists who enlighten us about lost tribes in the Amazon whose members, aborigines in an adamic state, believe that the territory of dreams is the academy of the jungle and the great temple of truth in which the gods speak to them and dictate to them about what is good and what is bad, the future that suits them, the cosmic sense of the past and the joys and sorrows of their ancestors, who contemplate the tribe’s wanderings in this world and celebrate or grieve for them, as they go. All this we take for granted. It is necessary to look for another empire of the unreal that is not the oneiric to find those spheres of the fictitious that nourish solid ideologies in so many and so many people who live like the faithful Claudio—subject to the powerful law of the imaginary, the fiction turned into obligatory dictate and in a manual of use for daily conduct. These spheres cannot but be concentrated in the immense map of ideologies, the conceptions of the world structured on granite moral conceptions or, vice versa and with equal generating force, the systematic absence of categorizations on what is ethical or convenient—some call it relativism, as others might call it, the annihilation of the sense of reality. There are people who go through life “with the upfront,” that is, with their “principles” like Attila’s horse; and others who trust everything to karma, to “I’ll be seeing you” and to sit at the door of the house to watch the corpse of the enemy pass by, etc.

Bubble makes bubble. That is the question that almost always determines our positions with respect to measurable reality based on immediate perception. The facts themselves have a minor—relative—importance; what matters is, in the first place, to what extent they fit in our emotional acceptance system; then the interpretation we make of them prevails and how they are classified in our scale of what is acceptable, from the very adequate to the extraordinarily reprehensible. This filtering of the factual concludes with the relevance of our reaction, from indifference to outburst, passing of course through the demonstrated capacity of negotiation that we are capable of maintaining with ourselves to convince ourselves of the future goodness of the present displeasure, the lesser evil and other sentimental alibis with which we human beings conform and adapt to practically everything.

Of course, if everyone does the same thing and we all establish the same system of relating to the world “outside the bubble,” then any position taken on any controversy seems legitimate. Indeed, it is. Everyone has the right to err as they please and no one is entitled to deny others their free will in this regard. What is not valid is deceit. Claudius cannot pretend to sleep and bark while pretending to sleep; it is no good to say that we dreamt that we threw ourselves off a cliff into the sea and fell into the realm of the mermaids and, therefore, in the real world we have to be named king of the mermaids. It is not worth arguing that the same deception is, in itself, an inalienable right—the right to change one’s mind. It is not a question of rights or principles but of verisimilitude—if yesterday’s certainties must be changed because circumstances have changed, then those certainties were worthless; it is logical: ideas that only serve when nothing happens are not ideas properly speaking but figurations, more or less well-intentioned, more or less interested conjectures. That is to say—a useless reverie transposed to the world of truth remains ob-scene—outside the scene—outside dream and reality, in the sterile territory soaked with the emptiness of the lie. And the lie, however it is said and however it is painted, will serve for many things but it is worthless. The theorist said that a lie is “a fiction whose verisimilitude is bankrupt and which contributes nothing to reality;” on the contrary, it debases it. And in the end, for what but to end up in nothing. For nothing.

José Vicente Pascual is a writer and novelist, living in Madrid. La Hermandad de la Nieve (Brotherhood of the Snow) is his latest work of historical narrative. This articles appears through the kind courtesy of Posmodernia.

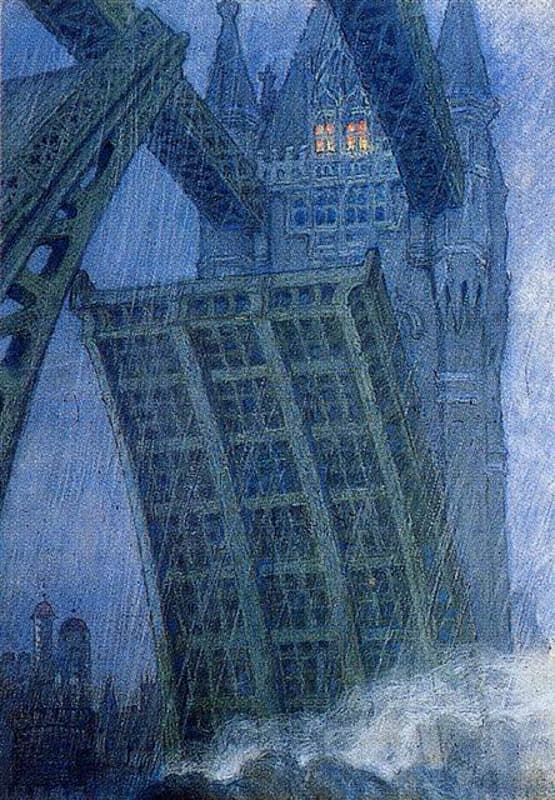

Featured: Bridge in London, by Mstislav Dobuzhinsky; painted in 1908.