This article, by Anne Morelli, is here translated for the first time complete. It is based on her monograph, Principes élémentaires de propagande de guerre (utilisables en cas de guerre froide, chaude ou tiède)—The Basic Principles of War Propaganda (For Use in Case of War, cold, hot, or warm), which was first published in 2001 and then revised and republished in 2010 to include the war in Afghanistan and Obama’s Nobel Peace Prize speech.

Morelli’s ten principles, or “commandments” are often accredited to Lord Arthur Ponsonby. Rather, Morelli summarized Ponsonby’s work, Falsehood in War-Time to formulate them.

The current Russian-Ukrainian conflict is just the latest iteration of the immense reach of war propaganda to fashion consent, in the form of ready sacrifice of blood and treasure.

Nearly a century ago, a British diplomat who had observed firsthand the creation of anti-German information in British government offices described these counterfeiting procedures at work during the First World War. This book by Arthur Ponsonby explained the basic mechanisms of wartime propaganda. However, these principles are not about the First World War—they were applied in all open conflicts, and also in the Cold War. They form the basis of the information war which is essential, more so today than in yesteryears, to win public opinion to a cause.

Ponsonby’s Ten Commandments

The principles identified by Ponsonby can be easily stated as ten “commandments.” I will state them here, and we will see for each of them to what extent they have been applied by NATO’s propaganda services.

- We do not want war

- The other side is solely responsible for the war

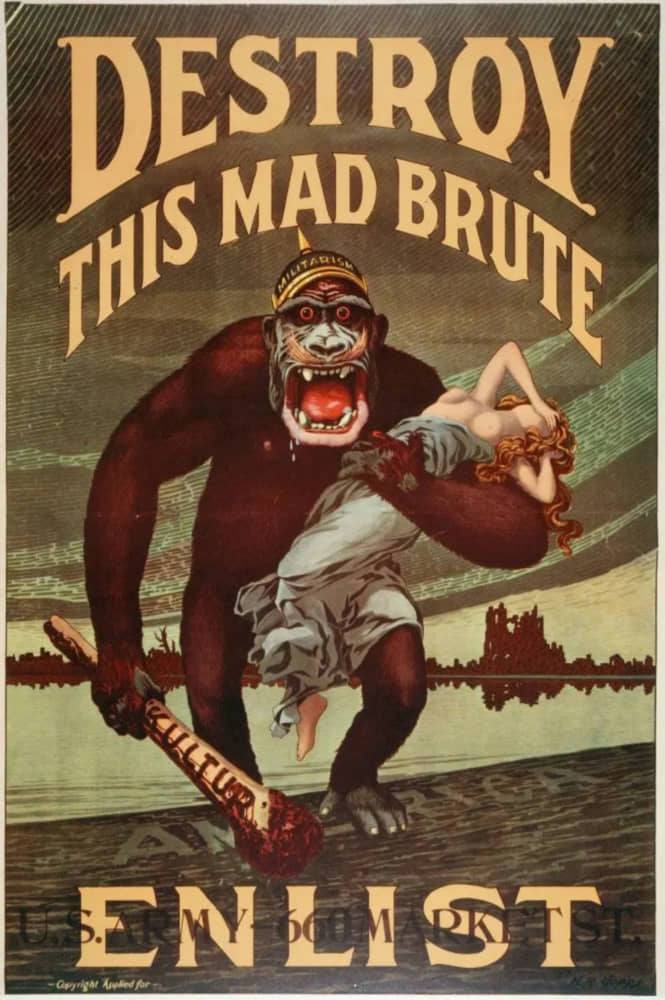

- The enemy has the face of the devil (or in the order of “ugly”)

- The real aims of the war must be masked under noble causes

- The enemy knowingly commits atrocities. If we commit blunders, they are unintentional

- We suffer very few losses. The enemy’s losses are enormous

- Our cause is sacred

- Artists and intellectuals support our cause

- The enemy uses illegal weapons

- Those who question our propaganda are traitors

1. We Do Not Want War

Arthur Ponsonby had early noticed that the statesmen of all countries, before declaring war or at the very moment of this declaration, always solemnly assured as a preliminary that they did not want war. War and its procession of horrors are rarely popular a priori, and it is therefore fashionable to present oneself as peace-loving.

During the war against Yugoslavia, we heard NATO leaders claim to be pacifists. If all the heads of state and government are motivated by a similar desire for peace, one can of course wonder innocently why, sometimes (often), wars break out all the same. But the second principle of war propaganda immediately answers this objection: for we have been forced to wage war; the opposing side began it; we are obliged to react, as self-defense, or to honor our international commitments.

2. The Other Side is Solely Responsible for the War

Ponsonby noted this paradox of the First World War, which can also be found in many previous wars: each side claimed to have been forced to declare war to prevent the other from setting the planet on fire. Each government would loudly declare the aporia that sometimes war is necessary to end wars. That time it would be the last war, “der des der” [last of the last].

The most relentless warmongers therefore try to pass themselves off as lambs and shift the guilt of the conflict onto their enemy. They usually succeed in persuading public opinion (and perhaps in persuading themselves) that they are in a state of self-defense.

I will not attempt to probe the purity of either side’s intentions. I am not trying to find out who is lying or telling the truth. My only purpose is to illustrate the principles of propaganda, unanimously used, and in the case of this second principle (“it is the other who wanted the war”), it is obvious that it has been applied many times during the NATO war against Yugoslavia.

On that occasion, European governments, slightly embarrassed by public opinion to be dragged into a conflict about which European parliaments had not been consulted, despite the constitutional obligation, in several countries, that such consultation take place, widely used in their propaganda the argument of the obligation in which the European countries found themselves to join the war.

Thus, in 1999, Christian Lambert, head of the cabinet of the Belgian Minister of Defense, replied to students who asked him why Belgium participated in the bombing of Yugoslavia, that it was an obligation for our country, by virtue of its membership in NATO. This answer was totally classical at that time, but did not correspond to reality. There would have been an obligation for European countries to participate in the war, if a NATO state had been attacked, but this was obviously not the case in the Yugoslavian war.

During this same war, the principle of “he started it” was in fact very widely applied by Western propaganda, and in particular in a form that Ponsonby had already pointed out: the enemy despises and underestimates our strength; we will no longer be able to remain on the sidelines; we will have to show him our strength.

Western propaganda in 1999 thus stressed that the Yugoslavs defied NATO and pushed it to respond with violence. Thus, the Brussels daily Le Soir wrote on January 18, 1999: “NATO finds itself challenged by astonishing cynicism. Will the world’s leading armed power be able to justify its wait-and-see attitude for long?”

NATO also claimed that it was reacting to a campaign of “ethnic cleansing” by the Serbs against the Albanians in Kosovo. With the passage of time, however, the international experts of the OSCE confirm the opposite thesis: when NATO began bombing Yugoslavia on March 24, Belgrade reacted with a systematic campaign of violence against the Albanian majority in Kosovo. Before March 24, police violence against Kosovo Albanians had been isolated; it was not “ethnic cleansing.”

But in order to convince Western public opinion of the validity of the bombing of Yugoslavia, it was necessary to make people believe that the war was a retaliatory one. It was the enemy who had to bear the full responsibility for the war, and more personally its leader. The war was the fault of Milosevic who, in his intransigence, refused Western proposals for peace in Rambouillet. The Franco-Belgian weekly Le Vif-Express ran this headline: “The dictator of Belgrade has a crushing responsibility in the misfortunes of the Serbian and Albanian people.” The insistence on the person of the leader of the enemy camp is not a coincidence. Ponsonby’s third principle insists on the need to personify the enemy in the person of its leader.

3. The Enemy has the Face of the Devil

It is not possible to hate a whole people globally. It is therefore effective to concentrate this hatred of the enemy on the opposing leader. The enemy thus has a face, and this face is obviously odious. One did not only wage war against the Krauts, the Japs, but more precisely against the Kaiser, Mussolini, Hitler, Saddam or Milosevic. This odious character always conceals the diversity of the population he leads and where the simple citizen may yield his alter egos.

In order to weaken the opposing cause, it is necessary to present its leaders as incapable, at the very least, and to cast doubt on their reliability and integrity. But, as far as possible, it is necessary to demonize this enemy leader, to present him as a madman, a barbarian, an infernal criminal, a butcher, a disturber of peace, an enemy of humanity, a monster. And the purpose of war is to capture him. In some cases, this portrait of our enemy may seem justified, but we must not lose sight of the fact that this monster is most of the time very approachable before the conflict and even in some cases after.

Since the Second World War, Hitler has been considered such a paradigm of evil, that any enemy leader must be compared to him. This was of course the case with Stalin, Mao or Kim Il Sung; but even more recently, all the “villains in service” have also had to bear the same comparison. It is no different with Milosevic, whom the Italian weekly L’Espresso presented on its cover under the title “Hitler-Sevic,” with one half of the face corresponding to Hitler’s face and the other to Milosevic’s.

Following the same script, and at the same time, Le Vif-Express presented, at the time of the first bombings of Yugoslavia, a very dark cover, displaying the left half of Milosevic’s face and on the right the title “L’effroyable [The Appaling] Milosevic.” Inside the magazine, in text supported by grim and worrying photos of the Yugoslav leader, we learned that Milosevic’s capacity for trouble-making was far from being exhausted. The man who, three years earlier had raised his glass with Chirac and Clinton, during the peace agreements of Bosnia, signed in Paris, was now a neurotic whose two parents and even his maternal uncle had committed suicide, obvious symptoms of a hereditary mental imbalance.

The Vif-Express did not quote any speech, any writing of the master of Belgrade, but simply noted his abnormal mood swings, his explosions of anger, sickly and brutal: When he got angry, his face became twisted. Then, instantly, he could recover his composure. His wife was pushy, ambitious and unbalanced, whose psychological problems dated back to the fact that she was acknowledged late by her father. And the weekly concluded: Slobo and Mira are not a couple; they are a criminal association.

The technique of demonizing the enemy leader is effective and will probably continue to be applied for a long time. The reader and the citizen need clearly identified “good guys” and “bad guys,” and the most simplistic way to do this is to call the “bad guy” a new Hitler. Anyone who might not necessarily defend him, but even doubt that he is the precise incarnation of evil, is immediately disqualified by this comparison.

4. The Real Aims of the War must be Masked under Noble Causes

Ponsonby had noted for the 1914-1918 war that one never spoke, in the official texts of belligerents, of the economic or geopolitical objectives of the conflict. Not a word was said officially about the colonial aspirations, for example, that Great Britain expected and which would be fulfilled by an Allied victory. Officially, on the Anglo-French side, the goals of the First World War were summarized in three points:

- to crush militarism

- to defend small nations

- to prepare the world for democracy

These objectives, which are very honourable, have since been copied almost verbatim on the eve of each conflict, even if they do not fit in with the real objectives.

In the case of NATO’s war against Yugoslavia, we find the same discrepancy between the official and undeclared goals of the conflict. Officially, NATO intervened to preserve the multi-ethnic character of Kosovo, to prevent the mistreatment of minorities, to impose democracy and to put an end to the dictator. It was to defend the sacred cause of human rights. The war did not need to end even to realize that none of these objectives were met; that we were far from a multi-ethnic society; and that violence against minorities is a daily occurrence—but the economic and geopolitical goals of the war, which had never been mentioned, had indeed been achieved.

Thus, without having officially having claimed it, NATO’s sphere of influence had been significantly enlarged in Southeast Europe. The Atlantic Organization thus established itself in Albania, Macedonia and Kosovo, regions that were previously “resistant” to its installation.

Moreover, from an economic point of view, for Yugoslavia, which was “resistant” to the installation of a pure and simple market economy and which still functioned with a large public market, it was “proposed” in Rambouillet that the economy of Kosovo should function according to the principles of the free market and be open to the free circulation of…capital, including that of international origin.

One might innocently ask what connection there can be between the defense of oppressed minorities and the free movement of capital, but the first type of discourse obviously conceals less avowed economic goals. Thus, 12 large American companies, including Ford Motor, General Motors and Honeywell, sponsored the 50th anniversary summit of NATO in Washington, in the spring of 1999. Some thought that this was a totally disinterested move, while others thought that it was a “give and take,” and that the bombing of Yugoslavia, by destroying the country’s socialist economy, made room for the multinationals that had long dreamed of setting up a large construction site and doing good business there.

NATO spokesman Jamie Shea announced that the cost of the military operation against Yugoslavia would be more than offset by the longer-term benefits that the markets could realize. From September 3, 1999, the Deutsche Mark became the official currency in Kosovo, and the Zastava car factory in Kragujevac, which I had seen in May destroyed by the NATO strike of April 9, was snapped up by Daewoo in July.

The real aims of the war were perhaps not totally humanitarian, but the main thing was to make people believe that they were, at the time of the launching of the operations, when public opinion doubted the validity of this attack. The public was persuaded that they had to intervene against “bandits”, “criminals”, “assassins.”

This is also one of the basic principles of war propaganda: the war must be presented as a conflict between civilization and barbarism. To do this, it is necessary to persuade the public that the enemy systematically and voluntarily commits atrocities, while our side can only commit involuntary blunders..

5. The Enemy Knowingly Commits Atrocities. If We Commit Blunders, They are Unintentional

Stories of atrocities committed by the enemy are an essential part of war propaganda. This is not to say, of course, that atrocities do not occur during wars. On the contrary, murder, armed robbery, arson, looting and rape seem to be commonplace in all circumstances of war and the practice of all armies, from those of antiquity to the wars of the 20th century. What is specific to war propaganda, however, is to make people believe that only the enemy is accustomed to these acts, while our own army is at the service of the population, even the enemy, and is loved by them. Deviant criminality becomes the symbol of the enemy army, composed essentially of lawless brigands.

During the First World War, the Germans accused the Belgian and French “francs-tireurs” of the worst atrocities who, flouting the laws of war, treacherously attacked German soldiers and deceived them by their ruses, as for example by offering them coffee with strychnine. On the Belgian and Anglo-French side, the rumor that the Germans had systematically cut off the hands of Belgian babies circulated non-stop.

Moreover, the fear of the Belgian population, following these rumors, triggered an unprecedented exodus of refugees. One million three hundred thousand Belgians left their homes at the time of the German invasion in 1914. This exodus of “poor Belgian refugees” and the imaginary episode of Belgian babies with their hands cut off were used to the full extent by Allied propaganda to bring hesitant countries, such as Italy, into its camp.

During the war against Yugoslavia, the propaganda technique was obviously similar. Before the start of the bombing, William Walker circulated the news that the Yugoslav police had massacred civilians in Racak in January 1999, and it was officially announced in the Western media that the Serbs were carrying out systematic ethnic cleansing in Kosovo. The figures quoted at the time spoke of 500,000 victims of “genocide,” most of whom were buried in mass graves. Some commentators even suggested that bodies were burned in former industrial sites, which obviously evoked Nazi crematoria.

It is now known that in Racak, it was KLA troops (and not civilians) who were decimated. French troops finally invalidated the hypothesis of cremations in industrial vats; and, after long and meticulous research, Spanish forensic scientists have estimated the number of people killed in Kosovo at a maximum of 2,500, on both sides and including individual deaths for which no one can be accused.

Even the American weekly Newsweek headlined, after the end of the bombing, “Macabre mathematics: the count of atrocities decreases.” But it didn’t matter at that point because the war was over. The official lies had mobilized public opinion at the right time to gain its approval and we could turn to more serious assessments.

In the autumn of 1999, it was also possible for Western journalists to explain how they had been manipulated by KLA agents to broadcast “bogus” testimonies on television. For example, the journalist Nancy Durham, working for the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation (CBC), whose moving report on the murder of an 8-year-old Albanian girl, with the testimony of her older sister, was shown on more than ten channels—and later it was revealed that she had been deceived by her Albanian informers. But she was refused a correction that demonstrated the lie.

As for the mass graves and concentration camps, the terms seem in retrospect to be inadequate to the reality. In the spring of 1999, there were obviously murders, looting, torture and burning of Albanian houses. But one “forgets” to highlight with the same acuteness the same atrocities committed from the summer onwards on Serbs, Bosnians, Roma and other non-Albanians. Their exodus was passed over in silence, whereas the images of Albanian refugees from Kosovo and their reception abroad had been the subject of entire television programs. This is because the fifth principle of war propaganda is that only the enemy commits atrocities. Our side can only commit “mistakes.”

6. We Suffer very few Losses. The Enemy’s Losses are Enormous

During the Battle of Britain in 1940, the British greatly “overestimated” the number of German planes shot down by British fighter and the D.C.A. The Nazis, on the other hand, tried as long as possible to disguise their defeat on the Eastern Front and proclaimed resounding losses for the Soviets, without mentioning their own losses.

This old tactic was also used in the war against Yugoslavia. The West claimed to have zero losses on its side and inflicted huge military losses on the Yugoslav army. Thus, to justify the usefulness of the strikes, Western propaganda spoke of hundreds of Yugoslav tanks being put out of action. A year after the war, Newsweek was able to admit that only fourteen Yugoslav tanks had been hit by the 1999 air strikes.

7. Our Cause is Sacred

God’s support for a cause is always an important asset, and for as long as religions have existed, we have happily killed each other in the name of God. War propaganda must obviously make public opinion believe that “God is on our side;” or, at the least, ecclesiastics must give their support to the war by declaring it “just.” Let us remember that the good St. Bernard exhorted the knights of Christ to work for Christ by killing infidels. “Got mit uns” was the slogan displayed by the German soldiers of the First World War on their belts. This slogan was answered by the English “God save the King,” while the Cardinal Primate of Belgium, Cardinal Mercier, in his pastoral letter, “Patriotisme et endurance” (Patriotism and Endurance) did not hesitate to proclaim that the Belgian soldiers, dying in the fight against Germany, redeemed their souls and secured a place in heaven.

In the NATO war against Yugoslavia, while some French and American bishops spoke out against the use of force, others justified the bombing. Thus, Archbishop Jacques Delaporte of Cambrai, president of the Justice and Peace Commission of the French episcopate, approved in the pages of Le Monde of the air strikes as an ethically necessary action, while Archbishop Miloslav Vlik of Prague justified NATO’s intervention by relying on the doctrine of the Church: The international community is not only authorized, but also obliged to prevent the murder of the Kosovars and to restore their right to return to their homeland. Such positions obviously legitimized the “regularity” of the use of violence against Yugoslavia in the eyes of Western public opinion.

8. Artists and Intellectuals Support our Cause

During the First World War, with a few rare exceptions, intellectuals massively supported their own side. Each belligerent could largely count on the support of painters, poets, musicians who supported, by initiatives in their field, the cause of their country.

In Great Britain, King Albert’s book brought together the propaganda work of painters and engravers who “launched” the glorious image of King Albert, King Knight. In France, the caricaturists Poulbot and Roubille put their talent at the service of the Fatherland. In Belgium, the artists Ost and Raemaekers specialized in the making of tragic images evoking the martyrdom of Belgian refugees or the heroic image of the Fatherland. In Italy, the poet Gabriele d’Annunzio was the champion of such action. In Germany, in October 1914, 93 intellectuals, including the physicist Max Planck, the Nobel Prize winner and philologist von Willamovitz, the historian G. von Harnack and many professors of Catholic theology, signed a manifesto in support of their country’s cause and the honor of their army, which, according to this manifesto, was the victim of odious slander.

For the NATO war against Yugoslavia, it is no longer a matter of composing beautiful heroic music or making moving drawings. But the caricaturists are largely put to work to justify the war and to depict the “butcher” and his atrocities, while other artists work, camera in hand, to produce edifying documentaries on the refugees, always carefully taken from Albanian ranks, and chosen as much as possible in relation to the public to which they are addressed, such as that beautiful blond child with a nostalgic look, supposed to evoke Albanian victims.

Almost all the French intellectuals followed the official position of their government with articles of support in the press and interviews in the media. Such was the case—obviously—of the “philosopher” Bernard -Henri Lévy, being intervieed throughout the war on various French radio channels and in the newspaper Le Monde to justify the bombardments against Yugoslavia. But many other French “intellectuals” (Pascal Bruckner, Zbigniew Brzezinski, Didier Daeninckx, Jean Daniel, André Glucksmann, Philippe Herzog, the geographer Yves Lacoste) showed the same political servility.

9. The Enemy uses Illegal Weapons

There is nothing like affirming the deceitfulness of the enemy in war propaganda by assuring that he fights with “immoral” and condemnable weapons. Even if the basic idea is absurd—that there is a “noble” way of waging war with “chivalrous” weapons, which is obviously our way, and a barbaric way of waging war with “savage” weapons, which is that of our enemy.

During the First World War, and the controversy is on-going as to who, France or Germany, started to use asphyxiating gases. Each belligerent put off the sad priority of this use onto the enemy, thus assuring that he himself only “copied” the enemy’s weapons by obligation.

On September 1, 1939, during his speech in the Reichstag, announcing the invasion of Poland, Hitler himself stated that he had humanitarian concerns regarding the use of weapons. He would have tried to limit armaments, to suppress certain weapons, to exclude certain methods of warfare that he considered incompatible with the law of nations.

During the Korean War, it was the communist camp that accused the United States of waging germ warfare, which was far from being proven.

During NATO’s war against Yugoslavia, this old principle of war propaganda, noted by Ponsonby, was reused. Indeed, when the Yugoslavs revealed in June 1999 the use by NATO of depleted uranium weapons, with immeasurable human and ecological consequences, it was not necessary to wait long for the response. By August 1999, the Western media claimed that the Yugoslavs had used chemical weapons in Kosovo, thereby transgressing the rules of “civilized” war.

10. Those who Question our Propaganda are Traitors

Ponsonby’s last principle is that those who do not participate in the official propaganda should be ostracized and suspected of intelligence with the enemy.

During the First World War, pacifists of all countries had already learned the hard way that neutrality was not possible in wartime. He who is not with us is against us. Any attempt to question the accounts of the propaganda services was immediately condemned as unpatriotic or, better still, as treason.

During the war against Yugoslavia, the same scenario took place in the West. NATO’s media tactic was to produce daily news that was taken up by the soldier-journalists. Annoying opponents were systematically dismissed, with the exception of a few open forums that were not very well attended, serving as an alibi to show the pluralism of information.

When the “genocide” of the Kosovo Albanians was announced, for example, anyone who expressed doubts about the extent of this phenomenon was called a “revisionist,” a term that carries a lot of weight, since it is generally used to designate those who deny that Nazism organized the systematic extermination of the Jews.

In France, it was the Régis Debray affair that crystallized passions. On his return from Kosovo, Debray contested, in a letter to the President of the Republic Jacques Chirac, the reality of “ethnic cleansing” in Kosovo.

Immediately the media, led by Bernard-Henri Lévy, author of a response entitled “Farewell to Régis Debray,” organized a public lynching. Daniel Schneidermann wrote that Debray “slapped the refugees from a distance;” Pierre Georges called him a “false journalist,” “burdened by his prejudices,” “ridiculously naïve” and said that he had accumulated “elementary errors” and produced “a fragmented and totally questionable account.” Alain Joxe, declared him an “international cretin,” in league with the ideas of Milosevic and an accomplice of the Serbian fascist regime against which the U.C.K. fought “practically without weapons.” At this point, some cleverly recalled that Régis Debray was a former companion of Che Guevara. Regarded now as a revisionist, the accusation of being a red-brown traitor became clear. In times of war, asking questions is heretical.

The weekly magazine L’Evénement never hesitated to publicly denounce, to the opprobrium those that it denounced, “Milosevic’s accomplices,” and whose photos it published. Meshed together in this camp of the “traitors” were the historian Max Gallo, the Abbé Pierre, Monseigneur Gaillot, General Gallois, the film director Carlos Saura, the singer Renaud, the playwright Harold Pinter and the sociologist Pierre Bourdieu. For being suspicious of the official propaganda, they were accused by the Parisian weekly of having “chosen to brandish the great Serbian banner,” of having gone over to the enemy.

Conclusion

As we can see from these examples, the ten “commandments” of war propaganda described by Ponsonby have lost none of their relevance in almost a century. Have they been applied intuitively by NATO propaganda officers or by following the grid that we ourselves have followed? It is always risky to think that propaganda is built by systematically staging it, according to a meticulous plan; and one would rather believe that the possibility of improvement has criss-crossed the old Ponsonby principles.

However, one should not forget that the Nato spokesman who orchestrated all the propaganda for the war against Yugoslavia was Jamie Shea, who was not an uneducated military man. A graduate of Lincoln College, Oxford, he looked at the role of intellectuals in the First World War as his final thesis. His academic perseverance was crowned by a socially enviable position as head of NATO’s propaganda services. Thus, it is also safe to assume that Jamie Shea learned, as my Historical Criticism students do every year, the basic principles of war propaganda and carefully and systematically applied them in the propaganda campaign he was asked to orchestrate.

Anne Morelli is a Belgian historian at the Université Libre de Bruxelles (ULB).

Featured image: American propaganda poster by Harry Ryle Hopps, published 1917.