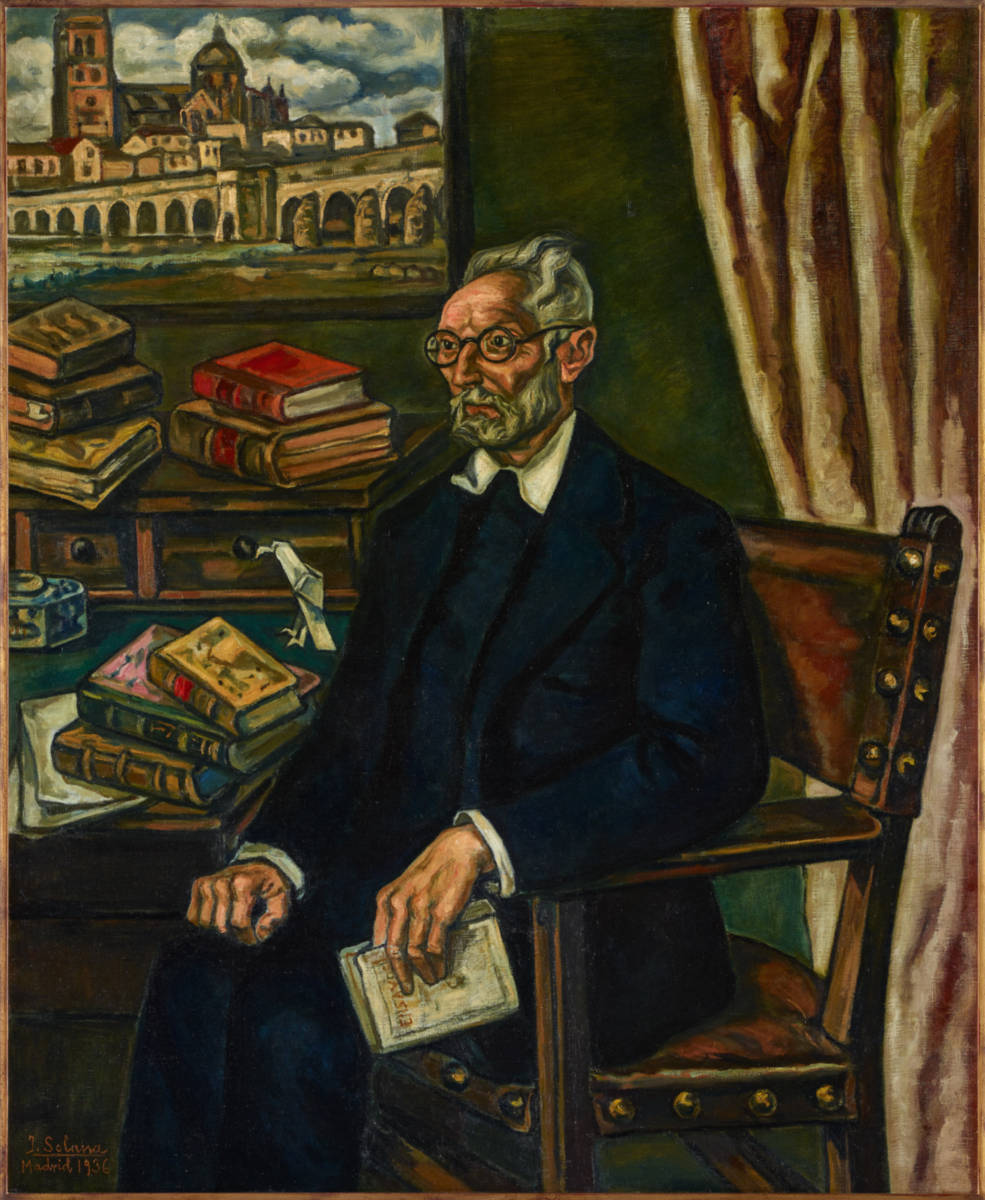

This month, we are greatly honored to present this interview with Professor Andrzej Nowak, a Polish historian and a public intellectual. He is a professor at the Institute of History, Jagiellonian University, Krakow, and is the head of the Comparative Imperial Studies Section at the Polish Academy of Sciences.

Professor Nowak has lectured as a visiting professor at Columbia University, Harvard University, Rice University, the University of Virginia, University of Cambridge, and University College, London. He is also a recipient of the Order of the White Eagle – Poland’s highest order.

He is the author of over 30 books, among them a multivolume history of Poland, Między nieładem a niewolą. Krótka historia myśli politycznej (Between Disorder and Captivity. A Short History of Political Ideas), Metamorfozy Imperium Rosyjskiego: 1721-1921 (Metamorphoses of Russian Empire), and History and Geopolitics: A Contest for Eastern Europe, Russia and Eastern Europe.

He is interviewed by Dr. Zbigniew Janowski, on behalf of the Postil.

Zbigniew Janowski (ZJ): Thirty years ago, when we met, you were a scholar of Russia. You had published several books on the topic. They drew the attention of Andrzej Walicki and Richard Pipes, two well-known experts on Russian history. Now you are writing about the history of Poland. Thus far you have written four out of ten intended volumes. Could you briefly describe your intellectual trajectory? What made you leave Russian history?

Andrzej Nowak (AN): Indeed, my research interests began with an analysis of the concept of the multiplicity of civilizations by Nikolay Danilevsky, a contemporary of Dostoevsky, an ideologue of Russian Pan-Slavism. That was forty years ago.

In recent years, however, I have returned to the history of Russian imperial thought. In 2018, I published an extensive volume of studies on the manifestations of this thought in Russian culture, from the time of Peter the Great to the formation of the group of so-called Eurasianists during the First World War. I am still interested in Russian topics. Not only because it is fascinating in itself, but also because of its numerous connections with the history of Poland to the present day. For Russia, over the centuries, Poland has been the first obstacle on the way to Europe, leading to its subordination.

Marx expressed it succinctly in 1863, when he wrote that “the rebuilding of Poland meant the annihilation of (imperial) Russia, the cancellation of the Russian candidate for world rule” (“Wiederherstellung Polens ist die Vernichtung Rußlands, (die) Rußlands Absetzung von seiner Kandidatur zur Weltherrschaft”). The issue of neighboring Russia and its geopolitical significance has been my concern for a long time; and it is precisely the historical Russian-Polish relations and the comparison of two political cultures that have developed so differently in the two countries.

When it comes to the multi-volume history of Poland, for me it is an attempt to reread the specificity of Polish political culture, its rootedness in the European republican tradition (this issue has been discovered in recent years by such outstanding scholars as Quentin Skinner and Martin van Gelderen).

But has anyone pointed out that the term “Polish citizen” – civis Polonis – appears for the first time in a document from the mid-12th century? I found out about it while writing the first volume of my synthesis. Now that I am on volume five, which covers the 17th century, I wonder about the crisis of the republican system, as well as the geopolitical conditions of its duration (wars with Russia, Protestant Sweden, and Islamic Turkey).

Such issues give me a lot of intellectual pleasure – and also because they allow me to look at the present day, for example, of the European Union, from the point of view of the longest lasting union in the history of Europe: the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth (1385-1795). Why did this union end up being partitioned by its imperial neighbors? How did they use the mechanisms of republican freedom (veto, applied in the Polish parliamentary system until 1791)? These are not just historical issues. In each case, like a shadow, being a neighbor to Russia brings back the problem of the empire.

ZJ: Russia is fascinating. One reason is Russian literature: Pushkin, Lermontov, Chekov, Gogol, Pasternak, Bulgakov, and, above all, Tolstoy and Dostoevsky. No nation, I dare say, can claim to have so many outstanding writers. Yet Dostoevsky stands out among them. He is not just a great writer but a great thinker; one of the most insightful critics of Modernity.

If you want to understand the cultural malaise of the West in the 20th century, you turn to Nietzsche, Ortega y Gasset and Dostoevsky. “The Legend of the Grand Inquisitor” lays out all the fundamental problems of political and social organization. It is a real tour de force of political theory, which, matches only Plato’s considerations in The Republic. Chapters 7 and 8 of Notes from Underground, on the other hand, is an unsurpassed analysis of the dangers of the nascent scientific mentality, the danger of which was described in the 1950s by Jacques Ellul in his The Technological Society. Aldous Huxley, on the other hand, turned Notes into his Brave New World (1932) – which describes a soft totalitarianism, the world which we seem to be building.

On the one hand, Dostoevsky is a great prophet, who saw the future of the West, a future where the scientific mentality dominated everything and discredited the Past (tradition, religion, hierarchy, custom, history); and, on the other hand, Dostoevsky is the Russian sui generis. He is suspicious of the West, Western ideas, Western Christianity, and, let me add, who passionately dislikes the Poles for Poland’s Western orientation and Catholicism.

Czeslaw Milosz saw Dostoevsky as someone from a backward country, who realized the danger that Western ideas posed, which were flooding Russia at the beginning of the 19th century. Dostoevsky’s literary output is a short history of modern Europe. Do you agree with Milosz? And what is your attitude toward Dostoevsky?

AN: The term “backward country” of course implies that there are “progressive” countries which are the yardstick for the rest of the world. Such an attitude was adopted by Dostoevsky himself, fascinated by the ideas of Saint-Simon and Fourier, which he got to know in the circle of the young intelligentsia in St. Petersburg. The death sentence he was given for participating in this circle, and then exile, certainly came as a shock.

When, after Russia’s defeat in the Crimean War, the so-called “progressive countries” – Great Britain, France and Sardinia, saw a liberal “thaw” in domestic politics, so that Dostoevsky was no longer enthusiastic about following “progress.” He quickly saw that liberalism and the so-called the utopian socialism, which fascinated him earlier, had a common source. And it is a poisoned source – the belief that man can build a paradise on earth on his own, and that the West is close to this paradise; and countries such as Russia should intensely imitate the West, so that one day they may find themselves at least in the vestibule of this paradise.

Imitation of the West will end in the revolution of nihilism, the foretelling of which Dostoevsky already noticed in Russia. He described them in the form of two generations in Demons: the older generation – “rotten” liberals and the younger generation – radical revolutionists.

The same observations were made earlier by poets of the Polish Romantic emigration: Adam Mickiewicz and Zygmunt Krasiński. The latter, in the drama “the Undivine Comedy” of 1833, presented exactly the vision of total revolution as a rebellion against God, as Dostoevsky had done 40 years later. The difference is that for Krasiński, the criticism of the revolution and of the preceding evolution of Western civilization is an “internal” criticism – he mourns this crisis because it is his civilization. He would like to save it, like Joseph de Maistre; he would like the Polish nobility to support the collapsing dome of Saint Peter’s Basilica in Rome with their sabers.

Polish Romantic thinkers imagined that Poland could play the role of the last defender of the European classical and Christian moral tradition against the forces of decay.

On the other hand, Dostoevsky, along with a large part of the Russian intellectual elite, took a different perspective: the crisis arises from the very essence of the West, from the rebellion of the West (that is, Catholicism) against the only true faith that has been preserved by the Orthodox Church. This is the perspective of the criticism of the West that continues in Russian thought right up to Solzhenitsyn and contemporary ideologues of Putin’s era. There are also great Russian writers who refer to this tradition today, especially Zachar Prilepin, a contemporary Dostoevsky.

ZJ: However, one can raise the following argument: Poland, as a country, disappeared from the map of Europe in 1795. Polish nobility turned Poland into “a country for sale,” because they invented a political system that made the Polish state (and the regal power) weak. Its downfall was predicted by King Sobieski.

The idea that the Polish nobles can “support the collapsing dome” is – pardon me – a piece of rhetoric, which inscribes itself well within the context of the post-French Revolution world, but it misses the point. How could de Maistre think that one could entrust the fate of Christianity, Catholicism to the people who could not even manage the political affairs of their own country? If one looks for defense of Catholicism or Christianity, a better place than de Maistre, in my opinion, is Chateaubriand’s The Genius of Christianity and Constant essays on religion.

AN: Sorry for the misunderstanding. The vision of the Polish nobility supporting the collapsing dome of St. Peter was written by Zygmunt Krasiński, a Polish Romantic conservative. Yes, he was inspired by de Maistre’s political philosophy, but this was a vision of Krasiński, not of a Savoyard reactionary.

De Maistre saw, for a time, in tsarist Russia the hope of saving the European tradition, until he realized how much revolutionary fuel was in Russia itself. Krasiński’s vision assumed that the Polish nobility most consistently represented the traditions of Roman republicanism, combined with Latin Christianity. As a conservative, however, he considered original sin as the cause of the contamination of all worldly endeavors and projects. That is why he saw in the attitude of defending the traditions of European Christianity a heroic but futile act. Poland’s act is to defend a struggling Christian Europe desperately to the end, just as it fought desperately for the independence of the lost (also through its own fault) Poland. But she will win this fight alone. Only Providence can win this fight. We have a duty to fight; we have no guarantee of victory.

It seems to me that this attitude is absent both in Chateaubriand and in Constant. Their “bland,” more melancholic and cultural view of Christianity presents it as a beautiful adventure of the European past, which may be saved as a kind of museum monument in the modern world. Krasiński, on the other hand, sees the issue of Catholic Europe as a fundamental existential, dramatic choice – against “this world” created by the triumph of liberalism and capitalism.

This is a completely different kind of romanticism than the ethos found in Chateaubriand. I think more realistic – at least from today’s perspective. This does not mean, however, that I believe that “Polish nobility” or Poland simply had some unique opportunities to save tradition.

Poland itself is part of the European community of fate. People who consider themselves in some sense heirs of Krasiński, but also of John Paul II and Saint Faustina (a Polish nun who initiated the world cult of God’s Mercy), must look for those Germans who feel spiritual communion with Pope Ratzinger, those Italians who understand one’s identity in the spirit of the Catholic tradition; Spaniards who still know who Miguel de Unamuno was; the French who understand the choice of Pascal and Antoine de Saint-Exupery; The English who have in their spiritual heritage Thomas More, Cardinal John Henry Newman, J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis and Chesterton. We are all in one boat and we will drown together, or we will keep on going together. We will reach the shore as Providence decides. We have a duty to row, in spite of those who want to sink our boat now.

ZJ: But the fate of a nation, unless we understand it in Oedipian sense, is not sealed. Fate of countries lies either in having a strong culture which gives a people a specific national identity – different from others – or strong political institutions capable of sustaining that culture.

Poland is a unique example. After more than eight centuries, it disappeared from the map of Europe at the very end of 18th century. What happened was more a result of the malfunctioning of political institutions than a lack of national identity, which, let us recall, was forged in the historical process since 966 AD, when Poland became a Christian country. Poland had elected kings and a republican system of government, which led to political weakness.

If you look at the American debate (the so-called The Federalist Papers) how such a new political system should work, the Founding Fathers (Madison and Hamilton) thought of the legislative process as an attempt to reconcile the conflicting interests that take place in a society at large. Representatives of the states are supposed to represent the general attitude of the people they represent; they do not have a mandate to act or vote in a predetermined way. They are not delegates!

The Polish republican experiment was exactly the opposite. It was based on, first, the unanimity principle and, second, the “imperative mandate.” What the result of it was that the Polish Diet was prevented from being a deliberative assembly, like the English House of Commons around the same period.

As Willmoore Kendall, the translator of Rousseau’s The Government of Poland wrote, “Because of the former [liberum veto], it was improbable that any decision could be taken; because of the latter [the imperative mandate], minds were already made up, so why deliberate?”

Such a system left virtually no room for strong central government – the elected king – to govern effectively. The king was stripped of the power to govern, whereas the nobility could claim to enjoy “Golden Liberty.” But this liberty could be had only at the expense of the weak State and submission of the vast part of the population.

The American Founding Fathers, on the other hand, worked on the assumption that the people are free to participate, and the role of the government is to mitigate the conflicts. To prevent anarchy, or impotence of the government, the State – the federal government – had to have considerable power. Polish liberum veto, which made it possible for one person to veto the majority decision, was the opposite of the majority principle.

Can you very briefly explain how such a system came about? Were there any serious political thinkers – like Grotius, Hobbes, Locke – behind it? Or was it something that was spontaneously generated during the historical process?

AN: The system was modeled on a Roman one that lasted only a little longer. And it was not Grotius, Hobbes, or Locke who supported the creation of this system, but much more “serious thinkers” – Aristotle and Cicero first of all.

The founders of Polish republicanism modeled themselves on their works above all. They believed, somewhat anachronistically, that in the sixteenth or seventeenth century their republicanism could exist between Moscow – the “third Rome”- the Ottoman Empire, the Habsburg Empire and the Protestant military monarchy of the Swedes, the Commonwealth, i.e. the republic – as in Cicero or Aristotle (monarchia mixta), with the Polish nobility as equals, the Seym (the parliament) as a concilium plebis, the senate as the senate, and the king as an elected consul or princeps.

This is how Jan Zamoyski, influential co-founder of this system, imagined an extremely influential co-founder of this system. Zamoyski authored the Latin treatise on the Roman Senate, and was at the same time chancellor and hetman of the Republic of Poland at the end of the 16th century. He was the author of the concept of the free election of a king, in which every noble had an equal voting right. Thus, theoretically, it had the right to vote, active and passive(!), with several hundred thousand citizens of the Republic of Poland (in practice, the election of the king came from 10 to 40 thousand).

The right of veto was to secure the union with Lithuania. Lithuania was smaller than the Polish part of the union; it could always vote in the Sejm. Thanks to the right of veto, the Lithuanians could feel safer as a political minority. For the first time, a single veto, i.e., the vote of one deputy, broke the deliberations of the Seym only in 1652, that is, after a very long earlier period of efficient functioning of the Seym. The election instruction of the sejmik (imperative mandate), which elected a deputy to the Seym, was to guarantee the voting power of the local government.

There is no place here to analyze this system in detail, which was much more complex and effective (for at least 200 years) than the caricatures that Bodin or Montesquieu created on the basis of their ignorance and arrogance, or the ideological enemies of republican freedom, such as, Hobbes or Locke.

Let me refer you to the already available serious studies of this system, which can be found in English with Marc van Gelderen, Quentin Skinner, Anna Grześkowiak-Krwawicz, Edward Opaliński or Dorota Pietrzyk-Reeves, as well as the latest monograph by Richard Butterwick, published by Yale UP. (Light and Flame), which perfectly analyzes what you are asking about: the crisis of the Rzeczpospolita/Res Publica system in the 18th century and its repair in the legislation of the Great Seym in 1788-1792.

ZJ: I want to return to Russia, and explore a bit more the Dostoevsky question. As we said, he was Russian, Orthodox Christian, skeptical of science, which he thought was dangerous for man’s understanding of himself as a man endowed with free will, and thus responsible for his actions. As Dostoevsky observes in Notes, the belief that man’s behavior can be “tabulated and calculated” spells out the end of mankind.

Dostoyevsky understood that scientific thinking was bound to see man as a machine, whose life will be organized by the scientific state. This is the premise of Huxley’s “brave new world,” and, let me stress it, our world. We are daily bombarded by phrases such as “A new study shows…” “New research demonstrates…” Such phrases take away from us the power of making decisions about our individual lives.

Would you agree that for historical reasons, which brought Russia closer to Europe, early 19th century Russia became a focal point of Western civilization, where the problems of the modern West shone with much brighter intensity than in Western Europe. Nowhere – not in London, Paris, Berlin or even Warsaw – writers or philosophers reacted so intensely, as did Dostoevsky, at the thought of where the West was heading.

AN: But all that fascination with Russia, the “depth” of the Russian soul, which 20th century Western European writers discovered in Dostoevsky, can also be found in the great literature of Romantic Europe: in Adam Mickiewicz, Zygmunt Krasiński, but also in Shelley, Keats, and even earlier at Byron. The terrifying pattern of a “brave new world” can be found in the practical idea of the English philosopher, Jeremy Bentham.

To illustrate the relationship between the vision of horror, which Western thought was able to perfectly design, and the implementation of this vision, which was possible (for some time) only outside the West, e.g., in the authoritarian system of Russia, let me recall the history of the Panopticon. Jeremy Bentham had a brother, Samuel. Together they created a project of perfect supervision of imperfect humanity. They named it the Panopticon. They created it in Krzyczew (today on the eastern border of Belarus), which was occupied by Catherine II during the first partition of Poland.

Samuel Bentham found employment, like many world reform enthusiasts, in imperial Russia. Krzyczew and several thousand surrounding square versts taken from Lithuanian owners was given by the empress to her favorite Prince Grigory Potemkin. It was for him that the English engineer invented a new factory in the fall of 1786: a building with such a system of corridors and mirrors to be able to observe all its employees from one place. It was not about disciplining simple peasants in the area, but about supervising overseers brought in from England. To have control over every movement of those who are to act as “intelligence,” “professionals,” “elite.” This is the starting idea of the Panopticon.

Jeremy Bentham, who visited his brother in Krzyczew in 1787, was fascinated. He took up his idea and turned it into a project of an ideal prison, under the same name. He was ready to develop other applications of the same idea – apart from prisons and factories, also for hospitals and schools. See and supervise everyone without interruption. The prison inspector, playing this role, could, according to a utilitarian concept, combine business with pleasure: invite guests to his gallery, from which one could admire what the supervised do at any one time. Big Brother watches, controls and provides entertainment.

A union of perfect supervision, with the ideal of social transparency was to make life happy and safe (I recommend the movie The Circle from 2017, which shows perfectly how it works – and therefore destroyed by “right” criticism). Minimum pain, maximum pleasure. In England, the idea of the Bentham brothers was not realized – at least during their lifetime. In Russia, the younger brother did not manage to bring complete the factory: Potemkin sold Krzyczew in 1787 and set out to prepare the way for Catherine II’s triumphal journey from St. Petersburg to the Black Sea.

Samuel Bentham busied himself with the construction of Potemkin villages along the route. He returned to the idea of the Panopticon in 1806, when commissioned by Tsar Alexander I, he built such a school in St. Petersburg. A perfect prison according to the model of the Bentham brothers, including the US and Cuba, was only constructed with the use of electronic surveillance bracelets in Amsterdam, the capital of post-modern utility and pleasure (drugs plus euthanasia), in 2006.

ZJ: Dostoevsky’s suspicion of the West appears to be a distinguishing feature of the Russian mentality. But suspicion can translate itself into a political posture that one country assumes vis-à-vis other countries or civilizations. Suspicion can also produce a mentality which has a sense of its own of mission. Russia, like America, believes that it has a historical mission. Marquis de Custine, a French aristocrat who visited Russia, even prophesized that that the fate of the 20th century would be decided by Russia and America.

Let me quote here the 15th century letter by Philotheus of Pskov, which he wrote to the Grand Duke Basil III of Moscow: “The Church of Old Rome fell because of its heresy; the gates of the Second Rome, Constantinople, have been hewn down by the axes of the infidel Turks; but the Church of Moscow, the Church of the New Rome, shines brighter than the Sun in the whole Universe… Two Romes have fallen, but the Third stands fast; a fourth there cannot be.”

If you take the message of the letter to be an expression of a mind-set, there is Putin’s rule today, in that he sees nothing wrong with 74 years of Communist rule in Russia; he pours tears over the collapse of the Soviet Union as the greatest disaster of the 20th century. Russia’s aggressive posturing under Putin appears to be more than lack of civility, or even cynicism of a former KGB agent. Russia in Putin’s mind continues to be a country with a historical mission.

Arnold Toynbee, who used this letter in a chapter on Russia in his Civilization on Trial (1948), wrote: “In thus assuming the Byzantine heritage deliberately and self-consciously, the Russians were taking over, among other things, the traditional Byzantine attitude towards the West; and this has had a profound effect on Russia’s own attitude towards the West, not only before the Revolution of 1917 but after it.”

Ultimately, it would appear that today’s world expresses the ideas that go back to the sources of our civilizations: Eastern (Greek) and Western (Latin) Christianity, Eastern and Western Roman Empires, two different sets of political culture, political institutions. We find the echo of it in Dostoevsky too, in “The Legend of the Grand Inquisitor,” in his criticism of Caesaro-papism, don’t we?

AN: Russia is born with a sense of a threat to its civilizational identity; it defends itself against the specter of political and spiritual colonization. This is how the fundamental idea of Russia is formed: Moscow – the Third Rome. Ruthenia linked its identity with Byzantium, with the Orthodox center of civilization. In 988, at the time of Vladimir the Great’s choice of state religion for Kievan Rus, this Byzantine center seemed to be an unchallenged alternative to “Latin” identity. In the 15th century, this center collapsed.

Orthodox civilization was then the basis of identity of only one sovereign political center: Moscow. Triumphant “Latin” pressed on it from the West, and Islam from the South. If Moscow dies, all civilization will die. Civilizational violence threatens the Orthodox world primarily from the West, from the “Latin” side. Byzantium itself succumbed to the West’s temptation just before the fall, accepting the ecclesiastical union in Florence (Moscow rejects this temptation). However, at stake in this game is not only defense against civilizational violence. The fate of the world is at stake, since it is about defending not so much one civilization as such, but the only true religion and its place in the world. Philotheus, the monk of the Pskov monastery of Eleazar, writes about it, puts this thought into words and presents it as an ideal-mission addressed to the power of the Moscow principality.

Laid out for the first time in a message to Grand Duke Vasilii III (around 1514-1521) and elaborated in letters in the years following, the idea of Moscow – Rome III – became the best known and most frequently updated concept of Russia’s special mission from the 19th to the 21st century. Thanks to this, Philotheus can be considered the first intellectual in the history of Russia. He is not an official writing for the state.

He is, in a sense, a man from the margins (Pskov had only just joined Moscow in 1510), passionately experiencing public affairs, the affairs of his spiritual and political community and seeking to rescue it in the face of a new great “civilizational” challenge. He seeks this rescue in the sphere of ideas and suggests it to the authorities. He does not appear as an unconditional servant of this authority, but shows its immense responsibility to protect the great idea it reveals.

Philotheus also shows examples of the betrayal of this idea by the state power – in Rome I and in Rome II (Byzantium) – and the punishment of the inevitable fall that the government’s betrayal of the ideal entails. Philotheus teaches authority: “let him know… let him remember….” He sets the condition: “If you will arrange your empire well – you will be a son of light and an inhabitant of upper Jerusalem, and, as I wrote above, so now I say: beware and note that all Christian empires have joined in yours, that two Romes have fallen and the third is standing. There will be no fourth. Contrary to the widespread interpretation of this text, it seems that it is not an unequivocal expression of faith that Moscow will always remain Rome III, that it will certainly bear the burden of this responsibility. Moscow is also threatened with the “Sodom sin,” an internal apostasy warned against by the voice of a 16th-century “intellectual.”

Philotheus only states that Moscow has no one to replace it, in its great mission to save the truth and the world. If it collapses – Rome will certainly not exist; there will be no more truth and justice in the world. That is why Moscow must not be allowed to fall! This is the pathos of the mission assigned by Philotheus to the Orthodox empire, and thus the pathos of his own, “first intelligence” of the mission.

Combined with Moscow’s heritage of Rome – empire, strength, and Jerusalem – is the heritage of the spirit. And against the world in which “lies in evil.” In practice, to the ”Latin” and Western world, which in the 16th century, after an internal split connected with the Reformation, and which entered the phase of great colonial expansion and became an obvious source of the problem of modernization and, at the same time, Moscow gives models and techniques for solving it. Russia needs to strengthen its empire to save its spiritual identity from the threat from the West, and thus maintain the ability to salvage/save/liberate the whole world. This is how the thought of Philoteus is read by some in intellectual circles and is not without influence on contemporary public opinion in Russia.

ZJ: Hostility, mutual suspicion between the Russians and the Poles is well known. The Polish see Russians as aggressors, the country that dismembered Poland in the 18th century, that erased the Dutchy of Warsaw in the 19th century. The Poles fought the Russians in the 1919-1920 war, after Poland regained statehood in 1918, after 123 years. Finally, it was Soviet Russia which imposed communist rule on Poland after WWII. This is only a handful of historical events that shape the attitude of the Poles toward Russia. Putin’s hostile attitude toward Poland today can be seen as the continuation of “the old story.”

However, looking at Polish-Russian relationships in a long historical perspective, one can see a different picture. If one takes into account the Polish conquest of most of White Russia and the Ukraine – in the 17th century Polish forces came close to Moscow, but were driven out. Russia can see itself not as aggressor but as a victim of Western aggression, of Western or Latin Christianity against the true Eastern Christianity, the Orthodox Church. If you add to it Napoleon’s Russian adventure, then the German invasion, the feeling of victimhood gets more augmented. One could say, Russia’s imperial posture was never motivated by the desire to dominate others but was a defensive posture, a posture that Russia had to assume to save herself and her Orthodox faith. Can such an argument on behalf of Russia be made?

AN: Yes, Russia has for centuries justified its expansion with the need to obtain a “security buffer” that would protect it against aggressive neighbors from the East and West. When Moscow began its expansion in the 15th century, it occupied a territory the size of the state of Utah. She “felt” threatened by her neighbors, such as the Tver principality or the republic of Novgorod – she absorbed these neighbors.

Then she “felt” threatened by subsequent neighbors. In the West, it was Lithuania, which was joined in the 14th century by many small principalities of Kievan Rus (today’s Ukraine and Belarus), emerging from the rule of the Mongolian Golden Horde. Moscow then announced the ideology of “collecting Ruthenian lands” (which had never belonged to Moscow before).

Poland did not make any conquest of the lands of Belarus or Ukraine, but entered into a dynastic union with Lithuania in 1385 – and on this basis (the marriage of the Grand Duke of Lithuania Jagiełło with the Queen of Poland, Jadwiga), a state union was established, which for four hundred years united Poland and Grand Duchy of Lithuania, including the lands of today’s Belarus and Ukraine.

During these four hundred years, Moscow had been waging a series of wars in which it had finally taken all these territories, except for a small scrap of former Russia which was occupied by Austria as a result of the partitions of Poland.

At the same time, in the East, Moscow “felt” threatened by the remnants of the Mongolian Golden Horde, the Kazan, Astrakhan and Siberian khanates – and conquered them militarily in half a century (1550-1600).

Then, of course, it was “threatened” again by successive neighbors, small khanates, in Central Asia – it took them all by the mid-19th century. It also reached China at the end of the 17th century. And she felt “threatened” by China. However, it has not managed to permanently remove this threat, that is, to conquer China.

In the South, Russia “felt,” from the 16th century, “threatened” by Turkey and Persia, so it began to conquer their possessions, including Transcaucasia – Georgia, Armenia, Azerbaijan, as well as the Crimean Khanate on the Black Sea. It has not yet conquered Turkey itself (although that was the goal of Russian policy from the end of the 18th century). But she still “feels” threatened by Turkey. After the partition of Poland, under Catherine II at the end of the 18th century, Russia became a neighbor of Prussia. Of course, she “felt” threatened by the power of Germany united by Prussia in the times of Bismarck.

If we adopt such a logic of a threat that justifies defensive conquests only. Then let us note that from the 15th century to the end of the 18th century, Russia conquered on average about 60,000 square kilometers each year, combined territories of Maryland and Massachusetts. Each year, Russia was enlarging its territory in this way for over 300 years!

Stalin, in the name of this logic, persuaded Roosevelt to agree in Tehran and Yalta to give Russia (the Soviet Union) a “security buffer” covering all of Eastern and Central Europe, including Prague, Budapest, Warsaw, and including half of Berlin and Vienna. Of course, he still could not “feel” safe. Russia’s security can only mean to bring the whole of Eurasia under its control, from the Pacific to the Atlantic.

You can accept this reasoning only if you see in it an analogy to the American “Manifest Destiny.” But it is worth asking the opinion of the inhabitants of all the countries that first Moscow, then imperial Russia, and finally the Soviet Union, conquered in the name of Russia’s “sense of security” and the right to “self-defense.”

ZJ: Let us talk about 1989, the collapse of Communism in Eastern Europe, and 1991, the dissolution of the Soviet Union. Eastern European countries rushed to join the EU. Russia, on the other hand, is where it always was. For the Poles, Czechs, Slovaks, Hungarians, the citizens of the Baltic states – Lithuania, Estonia, and Latvia (former Soviet “republics”) – the motivation was not just economic but cultural above all. One could hear the language of “returning to Europe” after decades of the culturally foreign rule. What prevented Russia from getting closer to Europe after the collapse of Communism?

AN: We need to remember, Russia has formed its political and cultural identity as an Orthodox empire, in contrast, often, against Latin, that is, Catholic Europe. Under Mongol rule for two and a half centuries, it was, as it were, forcibly opened to Asia. Since the 15th century, Moscow, pursuing a policy of “collecting Ruthenian lands,” entered into intense diplomatic and trade relations with European powers: the Habsburg Empire, and the England of Elizabeth, in order to geopolitically surround its immediate neighbors.

However, Russia did not participate in the spiritual life of Europe, in the crucial period of the Renaissance. Only from the Baroque, actually from the end of the 17th century, does Russia interact with the intellectual currents animating European culture. At that time, however, Russia had already made a great march in the opposite direction to the former Asian steppe empires – from the Western end of the Great Steppe, over the Black Sea, it reached the Pacific; in the 17th century it began to border China, Korea, followed by Japan.

Such a geopolitically enlarged Russia could no longer enter Europe, “fit” in it. The intellectual challenge, often fascinatingly analyzed by Russian writers and ideologues, is not “Russia in Europe,” but “Russia and Europe.” Space – prostor – history and religion make up a deeply rooted political culture in Russia. Together they create a “mental map” on which the memory of Tchaikovsky’s ballets, Pushkin’s poems or Dostoevsky’s novels is not “evidence” of Russia’s Europeanness, but a reason for imperial pride, along with the equally grateful memory of Ivan the Terrible, Peter the Great, and Stalin.

ZJ: Let me go back one more time to 1989. One thing one notices is that the 1989 European dream in Eastern European countries is gone, and to some, the dream became a nightmare. Brexit is the prime example of that. The British sentiment can be said to be this – we did not sign up for that. We did not think our sovereignty would be limited to such an extent. This is what one hears in Budapest and Warsaw.

Recently, I asked a Polish politician – what do you think of a Polish Brexit? To my surprise, he said: “Nothing would make me happier.” Let me stress – this is not a view prevalent among Poles, most of them like where they are. But there is a considerable segment of Polish society which considers it as a serious intellectual option. The reason is the sovereignty of the Polish or Hungarian state, which EU crushes – the sovereignty that Poland was deprived of, first by partition and then the Soviet rule. It should not surprise anyone why Poles (but also others) are sensitive about a bunch of Euro-bureaucrats deciding their fate. You cannot be yourself – English, Polish, French, Italian – you must be a “European,” which means being a total abstraction.

A few months ago, I saw a headline in a major Polish newspaper: “EU must defend its citizens in Poland.” The article concerned so called minorities. According to the liberal Polish newspaper, they are EU citizens and therefore, Polish laws are violations of their rights as EU citizens. One wants to repeat after Bentham, it is nonsense on stilts, yet it is the de facto European reality. Was the post-communist dream false, or did the West change in the last 30 years?

AN: Both. The expectations of the intellectual opposition in Poland towards the West were certainly exaggerated. The image of the “free world” depicted in our imagination in contrast to the gray and openly oppressive world of the “Communist camp” was idealized.

At the same time, however, it must be remembered that the West in 1989 was still the West, politically represented by Ronald Reagan, Margaret Thatcher, and above all – John Paul II was in Rome. Back then in Europe they referred to the so-called founding fathers of the European Union, to their Christian-democratic roots: Konrad Adenauer, Alcide de Gasperi, Robert Schuman.

Marxism, after the obvious failure of this ideology in the countries under its authority, seemed finished, at least from our perspective. In 2020, you can see how Marxist inspiration fills the longest shelves with philosophy and politics in bookstores in Paris and London. As it dominates universities in Western Europe and our part of Europe, described in a postcolonial way as “new” (“new” democracies, “new” Europe, etc.), it actually follows these trends in a way that perfectly confirms the mechanisms described by some theorists of postcolonial studies.

However, part of the “intellectual layer,” and many so-called ordinary people, in countries with a strong historical and cultural identity of their own, such as Hungary, Poland or the Czech Republic, still keep the memory of the real experience of enslavement by the Communist logocracy, from which today comes the political correctness that dominates in the West and is imposed on us. That is why this new enslavement, this time coming from the West, is met with some resistance here.

However, fears of the real neo-imperialism of Putin’s Russia do not allow countries, such as Poland or Lithuania, to suddenly cut off from the European community, even in its present, disastrous shape. We can try to change Europe, stop this fatal process from within. This is what worries the Brussels, Parisian and Berlin political and intellectual elites. They ascribe to themselves the role of teacher and therapist for a “backward,” “sick” part of Europe (here the most frequently mentioned are Hungary and Poland).

In fact, I see in this attitude also a deep fear that the attitude of the elites currently ruling in Poland and Hungary, in matters of culture, customs, understanding of the European tradition – may turn out to be attractive to many Germans, French, Italians, and Spaniards – who do not necessarily want to run after the “bright future” promised by European progress officials. Many European people are looking to defend their common sense against ideological madness. Some people recall that Europe has always been rich because of its diversity and not of top-down centralization, and not by exchanging arguments about the good life, development models, and not by imposing “just the right approach.”

ZJ: What you have said makes me think of a famous sentence from John Stuart Mill’s On Liberty (1859): “Despotism is a legitimate mode of government in dealing with barbarians, provided the end be their improvement, and the means justified by actually effecting the end. Liberty, as a principle, has no application to any state of things anterior to the time when mankind have become capable of being improved by free and equal discussion. Until then, there is nothing for them but implicit obedience to an Akbar or a Charlemagne, if they are so fortunate to find one.”

Unlike democracy, despotism or autocracy, with which we associate the Orient and Russia, is not a political system or a theory of government. Rather, it is mode of governing a people. As a specialist on Russia, can you say that Mill’s words apply well to the state of Russian society at that time? In other words, is autocracy a system of government – the only force that could guarantee social and political order?

AN: I would disagree. Aleksander Wat, a Polish futurist poet who passed through nearly 20 prisons of Stalinist Russia during World War II, once gave a very good definition of the Soviet system – the absolute concentration of absolute power on an absolutely large area. An alternative to despotism (i.e., centralism) may be federalism – the development of regional self-government in a territorially large state.

Let me remind you that until the beginning of the 16th century, the Polish-Lithuanian state was larger in terms of territory than Moscow and until the partitions (in 1772) it was the second largest state on the European continent. And it was on such a large area that a system of decentralized authority was created, based on local self-government (district councils), which functioned well from at least the 15th to the 17th century.

As is known in the United States, this system continues. In Moscow, they also showed possibilities of developing a system of representation of the society several times: at the beginning of the 17th century, in the form of the so-called “earthly councils.” The movement of local, that is, earthly self-government, became strong again at the end of the 19th century – this is the self-government in which people like Chekhov and the heroes of his plays could find their place.

The defenders of despotism as the only recipe for the problems of the great state refer to one argument above all: if we do not have a tsar and we do not listen to him – then we will lose the empire. Putin successfully appealed to this argument after the last great experience of the crisis of the empire, which also coincided with the revival of Russian self-government – in 1991.

Ultimately, the dilemma faced by the supporters of this power for Russians (and not only for them) is – either size (grandezza as Machiavelli would say), or freedom – a liberta. You want greatness, give up your (republican, self-governing) freedom. At the same time, a new tone appears in this argumentation – state despotism (meaning the lack of civil self-government) can be reconciled with liberalism – economic and the right to privacy.

In the Russian philosophical tradition of Slavicism, there is such a contrast – the state is a heavy-duty power – and society willingly gives its burden to the people of power, and itself enjoys non-political freedom. And this is probably not only the Russian tradition, but the constantly reviving temptation to organize political life without citizens. There is only the state (and its guardians) – and on the other end – individual consumers.

ZJ: Could one say the same thing about China, and the Chinese leaders’ rhetoric that we have been hearing for about 20 years – that what China fears the most is anarchy. Ergo, the Chinese Communist Party is the sole guardian of social order; and since anarchy is worse than anything, despotism or autocracy is a legitimate way of governing the population. Some 15 years ago, Boris Johnson wrote a piece for the Spectator, where he accepted this view about anarchy in China, which makes me think that Chinese rhetoric works. Today Johnson is Prime minister, and what he thinks can translate into his country’s foreign policy.

AN: China has just adopted the model I outlined at the end of the answer to the previous question. Does this mean that it is the only model that suits the Chinese? After an intense indoctrination lasting for generations, one can get this impression. The Chinese from Hong Kong have a different opinion, however.

Please allow me to express my opinion on Prime Minister Johnson’s view and on Mill’s remark earlier cited. Well, I see them as a reflection of the imperial-colonial tradition, especially strong in the English (later also American) elites. Outside of Great Britain, and maybe even outside the club, which brings together the elite from Eton and Oxbridge, there are actually no gentlemen. There are barbarians all around – at least to the East of Germany are surely the habitats of barbaria. The barbarians living there can be cannibals, if that suits them, we – gentlemen from the club – will not hinder trading with them.

The most cynical example of this attitude I found in the liberal prime minister, David Lloyd George, who in 1920, when he initiated political negotiations with Lenin, said that he did not care about the political principles of these barbarians, let them even have the Mikado – it is their business, as long as they kill other barbarians (this is what Lloyd George meant about the Armia Czerowna – the Red Army – which at that moment was storming Warsaw). And let them get together as they please – this is their freedom. And this is our liberalism that we will not impose our political standards on them. We must reach an agreement with them, if they are so strong that without them it is impossible to establish a global order. This is a specific combination of liberalism (à la Lloyd George) and imperial Realpolitik.

In America, this is the approach of many – formerly Henry Kissinger, now John Mearsheimer. For me, this is a very short-sighted doctrine of appeasement – the false hope that aggressive despotism will feed on victims only from the circle of “barbarians.” Eventually, however, comes the moment when the “barbarians” start eating the gentlemen. Such is the logic of despotic empires. It is perfectly summarized by the saying of Bezborodko, Chancellor of Catherine II – what does not grow, rots. The despotic empire must continue to expand – otherwise it risks imploding. And they know this very well not only in Russia, but also in China. It is good that this has also been remembered in London and Chicago.

ZJ: Now that the Democrat Biden has become president of the United States, we will have a different foreign policy. If you were on the team of Russia advisers to the president, what would you say should be the US policy vis-à-vis Russia?

AN: President Biden will have other advisers. I can only express some concerns based on the historical experience with the presidents of the United States, who over the past three decades came from the Democratic Party and represented a left-liberal ideology. They were, let me remind you, Bill Clinton and Barrack Obama.

The former started with dreams of a “reset” with Russia. Fortunately, Russia was so weak during this period that it could not take advantage of this policy. The disaster happened under Obama, who has the blood of hundreds of thousands of people in Syria on his hands. His complete irresponsibility led to an escalation of the civil war and to the re-installing of Putin’s Russia as a key player in the Middle East.

Obama also made a significant gesture to Putin – he resigned from the project adopted by the previous administration (Bush Jr.) to install the so-called anti-missile shield in Poland. President Obama announced his decision to withdraw from this project, which was indeed very irritating to Putin and which strengthened the sense of security for Poland and the entire region of Central and Eastern Europe, on September 17, 2009. It was exactly the 70th anniversary of the Red Army’s invasion of Poland in 1939.

Putin may have felt invited to a new expansion – and he tried it in Ukraine. At that time, however, President Obama was probably instructed by people who knew the rules of world security better than him – and there was a certain reaction to the aggression in Crimea, and then in the Donbas.

What am I afraid of? That under the slogan of the fight for a “brave new world,” led again by liberal America, the US president will not recognize that it is not good stigmatizing smaller countries that do not accept this ideology and handing them over to Russia as “pariahs of the democratic order.” It does not have to be democratic or liberal, but it is very important to this vision of “restoring order” that it be fulfilled by restoring its former zone of domination (Ukraine? Maybe Poland? Maybe most of Central and Eastern Europe?).

In short, I am afraid of combining the slogans of the ideological “crusade” (actually, anti-crusade) inside the so-called Western community, understood as a community of LGBTQ+ rights and unlimited abortion – with a practical policy of the so-called realism in relations with non-Western empires such as Russia. The costs of such a policy would be paid primarily by the countries of the inter-imperial border, such as Poland, Lithuania, or – on the border with China – Korea and Taiwan.

ZJ: Given what you said about Russia and China, it seems to me to be only proper to invoke here two Frenchmen. In the 1830, they embarked on long trips in two different directions – Alexis de Tocqueville went to America; Marquis de Custine went to Russia.

Not much was known about the two countries. Before Tocqueville published his book, there were, I believe, only three or four books about America. Tocqueville’s and his young companion Beaumont’s books were the first ones to offer an exhaustive view of both the country and, above all, American democracy.

De Custine, on the other hand, was looking for an alternative to democracy. For Custine, in the words of Robin Buss, the English translator and editor of his Letters, “democracy meant mob rule and the dictatorship of public opinion, through rabble-rousing speeches and the press.” Encouraged by his friend Balzac and the Polish Count Ignacy Gurowski, he set out for Russia.

The fruit of his visit is Russia (1839), or The Letters from Russia.

By today’s standards, Tocqueville’s book is an international bestseller, and everyone who wants to understand democracy must read it. Given its success in the 20th century, the popularity of Tocqueville’s work is not surprising. However, the 21st century is different.

The rise of China with its autocratic style of government should be of concern to everyone. Russian democracy is a democracy in name only; for all intents and purposes it is a mild form of old autocracy. The difference between it and China is that the Chinese rulers do not hide their contempt for democracy, Xi Jing Ping openly says that the system is a failure. Both leaders share two things – the respective countries’ tradition of autocratic rule (strengthened in the 20th century by the experience of Communism) and the belief that only autocratic rule is capable of preventing a country from sliding into anarchy.

Would you agree that given democracy’s current performance in America and Europe, there is every reason to read de Custine’s account.

AN: People knew quite a lot about Russia in France before de Custine. Let us recall, for example, that the French Grand Army visited Russia in 1812, and two years later France was “returned” by the Russian army (Normandy was a Russian occupation zone for two years). A lot of arguments have already been gathered, both on the side of Russophobia and Russophilia.

The first French treaty stigmatizing the Russian political system as oriental despotism was published in 1771. It was written by Abbé Chappe d’Auteroche who visited Siberia (voluntarily), and Catherine II herself replied to him with a two-volume refutation of his arguments (I write about it at length in my recent book, entitled, Metamorphoses of the Russian Empire 1721-1921). This work, published immediately in French under the title Antidote and translated into English, was not only the defense of Russia’s right to the name of a European power, but also the justification of the autocracy.

As I argue in this book, in such a huge country as Russia, another form of power would lead to disintegration. The Russian system is not despotic, but a noble, enlightened absolutism, motivated by concern for the greatness of the state and the welfare of its subjects. So much for Catherine the Great. And it is so today, until the time of Putin’s apologists.

These arguments excellently convinced the French elite (and not only them). After all, Montesquieu said the same – this is why we should refer to de Custine’s work, because it helps us understand that the nature of the Russian despotic system is not autocracy itself, but above all lies, systematic, omnipresent, gradually disturbing cognitive abilities. The lie of the subjects against the authorities, the lie of the authorities against the subjects, and the systematic lie of the power of the Empire against its foreign partners.

No partner is actually a partner; each one is treated as an enemy to be deceived and manipulated. The KGB school, from which most of Russia’s current political elite hails, has raised this ability to lie to an incomparably higher degree than was possible in the days of Nicholas I and de Custine.

The contradiction of the various “narratives” that this Russian rule presents about itself is staggering. For the right wing, Putin is to be the “eschaton” of the Christian order, the last defender of the Cross against neo-paganism and Islam. For the Left (the propaganda of the Russia Today television station is addressed to this audience) – the last tough opponent of hated America, to some extent heir to Lenin’s Russia. For Western businessmen – a model of a good business partner. And so on. Whoever reads de Custine will understand the genesis of these narratives.

ZJ: Russia is not the only country that created national myths, such as the Third Rome. Other nations have this tendency too: Rule Britannia, the City on the Hill, the Third Reich, and many, many others.

The Poles – very much like the French – are obsessed with national history. They created a myth which is not about ruling the world but saving the Western World from barbarian onslaught. It is the myth of the antemurale chirstianitatis, the Bulwark of Christianity. The origin of it is not Polish. As far as I know, it was coined in 15th century, during the papacy of Pius II. It was Skadenberg, an Albanian Nobleman, who coined the term, which meant that Albania (and Croatia) was Italy’s Christian bulwark against the Ottoman Empire. Poles adopted it; it functions in Poland, but in Poland it means more than the fight against the Muslims or infidels at the battle of Vienna on September 11 (!) 1683, where the Poles defeated the Turks.

It is understood as antemurale against the East, Orient, the oriental despotism. It includes Russia as a barbarian force as well. Given the Christian (Orthodox) nature of Russia, is this historical vision justified; and using it against Eastern Orthodoxy, are we not in danger of creating a false historical imagination?

AN: I do not know if Poles are “obsessed” with national history. I have a different impression when I look at the youth which is protesting today in the streets of Polish cities with the most vulgar words, to emphasize their hatred for the Catholic Church, Christian tradition and the historical identity of Poland.

Let me make a comment on this issue. It is difficult, for example, for Belgium to be “obsessed” with its history, since it was created as a completely artificial state entity less than 200 years ago. It is difficult for Germany to express “obsession with history,” that is pride in its tradition, for obvious reasons. Simply put, nations have different histories, of different lengths, and different intensity as to how this history is experienced by social groups of different sizes. No one matches China in this respect. When you compare Poles with Jews, the Jews will undoubtedly turn out to be a nation much more “obsessed with their history.”

And now about the “bulwark of Christianity.” Again – a complete misunderstanding. The idea of a bulwark appears in Polish history in 1241 – during the great Mongol invasion. After the conquest of Ruthenia (Kievan Rus’ or Ruthenia!!! – not Russia), the Mongols moved to Hungary and Poland. On April 9, 1241, the prince of Poland, Henry the Pious blocked the way of the Mongols near Legnica. He led about 7000 – 8000 Polish and German knights, including 36 Templars. The prince was killed, the battle was lost, but the Mongols, having suffered heavy losses (similar to the parallel battle fought in Hungary), turned back.

The mood in Latin Europe at that time was truly apocalyptic. The fear of the Mongols as invaders from a completely different, completely alien world, as if of an invasion of the Martians, paralyzed the will of defense in many, but fired the imagination of no fewer people in the Latin West. Part of the Jewish communities scattered around the cities of the Reich were very excited about the news of the mysterious approaching Mongols. The Jews waited for liberation in the year of 5000 (1240/1241), which was exactly at this time on their calendar. There were also those who expected such liberation to come from the hands of the Mongols. In fact, some even saw in Genghis Khan the Messiah, the son of David.

After the defeat in Legnica, the echoes quickly reached even out to Frankfurt am Main, where the local Jews in May opposed with unprecedented audacity the baptism of one of their fellow believers who had freely chosen Christianity. It ended on May 24 with a terrible pogrom, which brought upon the Jews the fear of the Frankfurters and rumors of favoring the wild invaders from the East by the followers of Moses. The threatened rulers, including the Hungarian king Béla IV, the Czech king Wenceslaus I, Prince Frederick of Austria, and the emperor Frederick II Hohenstaufen himself, in letters, called for defense against the Mongols.

This was the context in which in Poland, Henryk the Pious, Legnica appeared, the heroic but lost fight on the Eastern fringes of the empire and Latin Europe. And this was the beginning of not only a myth, but a practical experience, the last (thus far) military act which, in Poland, is considered as having stopped the invasion of Central Europe by the Bolshevik Red Army in the summer of 1920, in the Battle of Warsaw. Legnica 1241 was most often mentioned in the journalism of the time. Will new experiences be added to this in the 21st century? I do not know, but I do not rule it out.

ZJ: Allow me to finish this conversation with a question which has been on my mind for many years. At the beginning of the 1990s, Poles coined the word “lustracja” (from the word “lustro,” mirror) which means “mirroring.” It is a made-up term that describes the process of making former communists, State apparatchiks, secret agents and collaborators accountable for their participation in building socialism.

In the post-communist societies people who did not support socialism, who suffered, who were persecuted or prevented from social advancement felt it necessary to expose those who upheld the system, who held power at the expense of the people who refused to participate in the Great Lie.

It was a form of showing the former commies and collaborators that their participation in the system was simply a matter of human indecency.

Unlike Poland, former Czechoslovakia, Hungary, and Russia have never undergone such a process – no moral or legal punishment for the former communists and collaborators. The old communists and collaborators, KGB agents, like Putin, became the lords of the New Russia. No such thing would be imaginable in Soviet satellite countries.

In your expert opinion, first, how significant has been the lack of “lustration” for the moral health of Russia, and, second, did the Russians realize what Communism did to Russia?

AN: The importance of this issue was best described by James Billington, an outstanding scholar of Russian thought and culture, in his book Russia in Search of Itself. Let me quote a key excerpt from the summary of this book: “There are essentially four ways that a nation can move beyond the fact of massive complicity in unprecedented evil. 1. Remove the problem from public consciousness. 2. Transfer the burden of evil to others. 3 . Evade the problem of evil in society by creating a noble personal philosophy for an elite. 4. Overcome evil by accepting the redemptive power of innocent suffering.”

This book was published in 2004. In 2020, it can be said that the official policy of remembrance in Putin’s Russia is a combination of the first two attitudes. The attitude most consistent with the Christian, Orthodox tradition, listed as the fourth in this list, has been marginalized.

As early as 2004, Billington was able to accurately pinpoint the cause of this state of affairs: “What is missing for this fact to open up broader redemptive possibilities for the Russian people is accountability, or even searching self-scrutiny, on the part of the Church itself.”

I am sorry to note that the lack of full accountability in a part of the hierarchy of the Catholic Church in Poland, for the cooperative spying of a small minority of priests with the communist police system in 1945-1989, also brings poisoned fruit into my country, Poland.

ZJ: Do you see any similarities between this and participating in all kinds of PC projects today – which is all morally questionable? Many people in the West, especially in academia, sold themselves to the Devil for the same reason that communists of old did. They are willing to justify today’s injustice in the name of future benefits. I am afraid, they, like the former commies will wake up from their dream of the better world, where all are equal and happy – very disappointed.

AN: Conformism, the lack of civil courage, is the most important, established and widespread feature of academia, at least in the humanities and social sciences. The ideology of “emancipation,” which today is the main instrument of the degradation of these areas, works – in my opinion – on a slightly different principle than you presented in your question.

In fact, under the lofty slogans of redressing past wrongs (towards women, animals, sexual minorities, and countries once colonized), professors of sociology, English studies, philosophy, political science, history and similar fields (displaced by new, more politically correct combinations) are ruthlessly fighting for their particular, current interests – for survival in a ruthless struggle. Survival of the fittest – this is the reality of this essentially amoral struggle, in which the stakes are a professorship, appearing on television, or the role of a social media star – and the alternative is the loss of a job, or experience of attacks by the media and environmental campaigns.

Adapt to the ideology currently imposed by the big media and their disposers – this is the method of survival. This is how the cultural revolution unfolds, more and more like the one that swept through China under Mao Zedong. Anyone who does not want the media and groups of students manipulated by it – to put on a “hat of shame” (as was done in China) – must join in stigmatizing colleagues who are still defending themselves against such degradation.

There is no labor camp waiting for them yet, but it is becoming more and more real to hand over those who still have the courage to think “incorrectly” to therapy, into the hands of therapists who will, anyway, remove “wrong” thoughts, concepts, and memories from their defiant heads. .

Probably no one has described the attitudes of intellectuals subjected to terror and the temptation to justify their cowardice better than the Polish poet Czesław Miłosz in his book, The Captive Mind. It is a book written in 1951 about the Polish intelligentsia conquered by the Stalinist diamat (dialectical materialism). This is also a book about the situation today at American and European universities. It is worth reading again.”

ZJ: Thank you, Dr. Nowak for this enlightening conversation.

The image shows, “Introduction of Christianity in Poland,” by Jan Matejko, painted in 1889.