III. Material Conditions of the Media

So, if “we” still have an enemy it is not those who challenge our cultures, for only in opposition to them do our groups have any meaning. Instead one must come to recognise that it is only through the group’s positive attributes, namely material conditions, that one can finds the true definition of who “we” are and therefore who our enemies are.

Thus, what truly endangers a group is not cultural outsiders, but those who deny the reality of material conditions as defining the group and see to hide it from us through a media-based ideology.

It was Marx who wrote in German Ideology “in all ideology men and their relations appear upside down, as in a camera obscura, this phenomenon arises just as much from their historical life process as the reversal of objects on the retina does from their directly physical life process” It can still be true to say that media is the domain of dispute even if the target of the cultural weapons that the media produces are not the true enemies of the exclusive “we”.

If as Marx suggested, the “superstructures” of every person’s life are defined by the “infrastructure” to which they are exposed then one starts to realise then the true division which exists in our society is not the one defined by cultures, for that is a symbiotic division, instead it is a division which runs along the lines of media infrastructure.

Effectively there are two tactics which can be adopted by the media in the liberal order to distract the exclusive “we” from realising who the true enemy is.

The first is to distract us from the truth by creating an illusionary enemy. The media/culture industry does this through a variety of means but draws strongly always on the idea of the cultural enemy to distract us. Social media in particular endlessly presents the Muslim, the black man, the person of another political orientation as being the enemy.

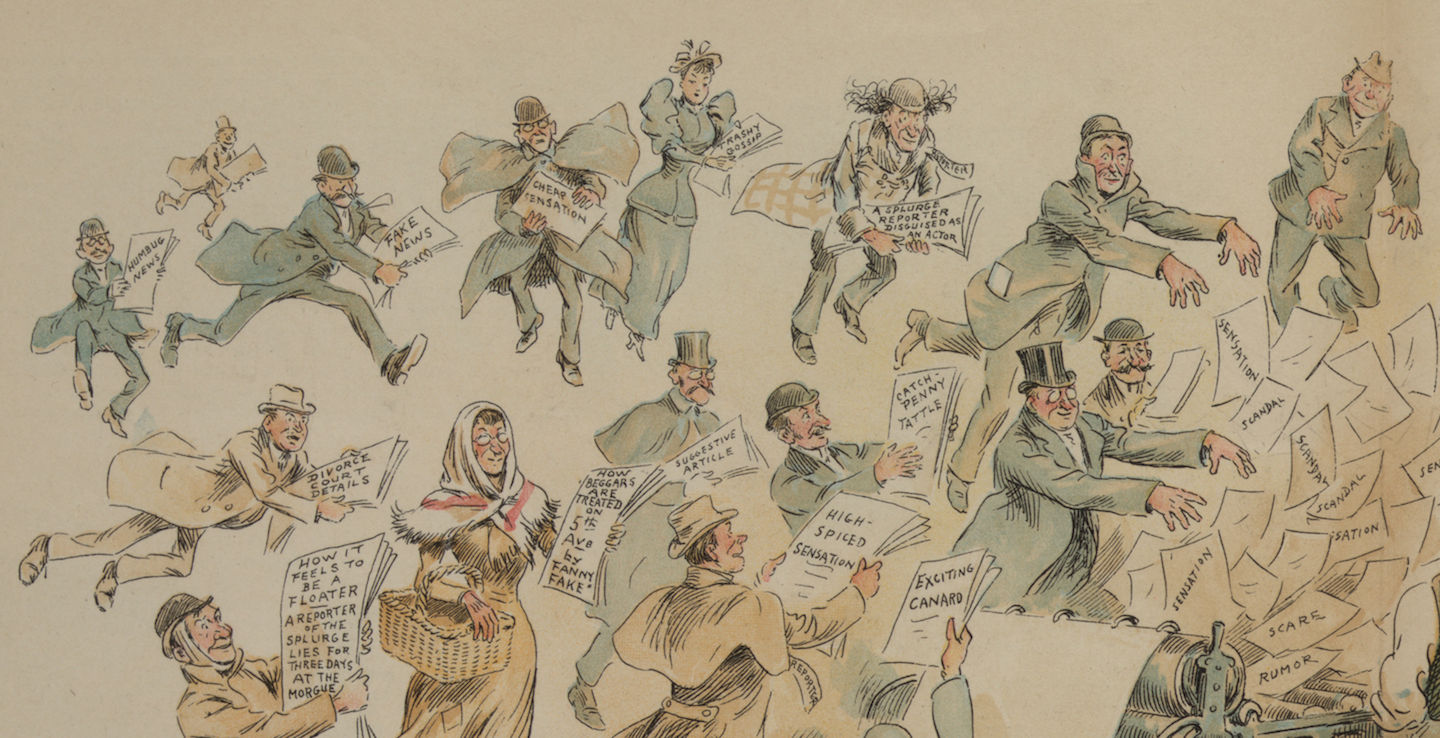

What has become popularly described as fake news, feeds people disinformation which says that a group with some different culture is the fundamental enemy of the group, without needing to say it explicitly. Although as has already been demonstrated they are needed for other cultural groups to have meaning.

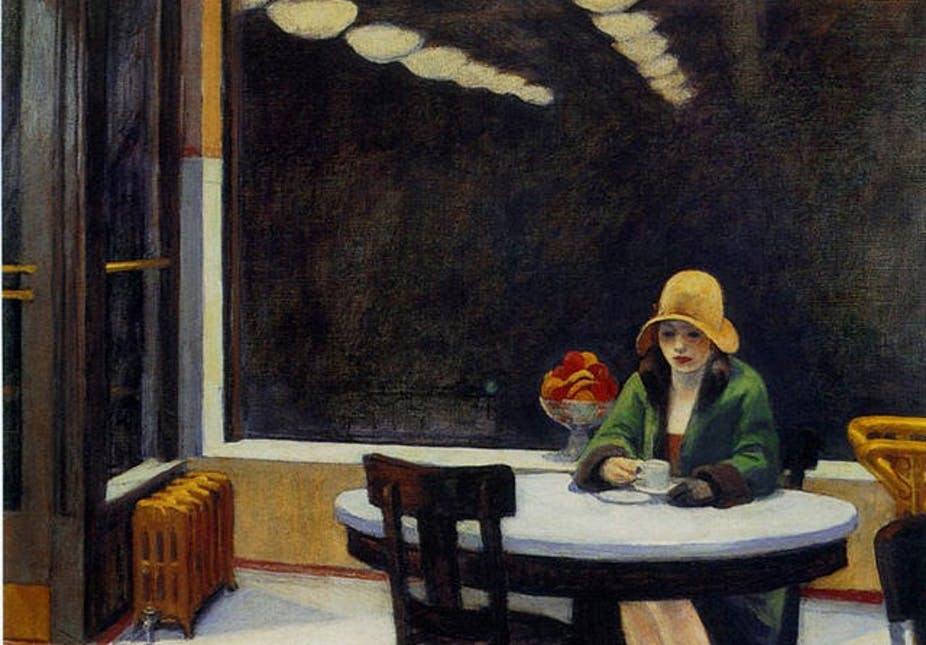

But then the second, perhaps far more insidious method, is that in admitting that the enemy on the screen is an illusion to promote the idea that there is no struggle at all, that there are no enemies to fight against. To tell those people who try to fight against an enemy then they are ill, just as Nietzsche predicted of the last men.

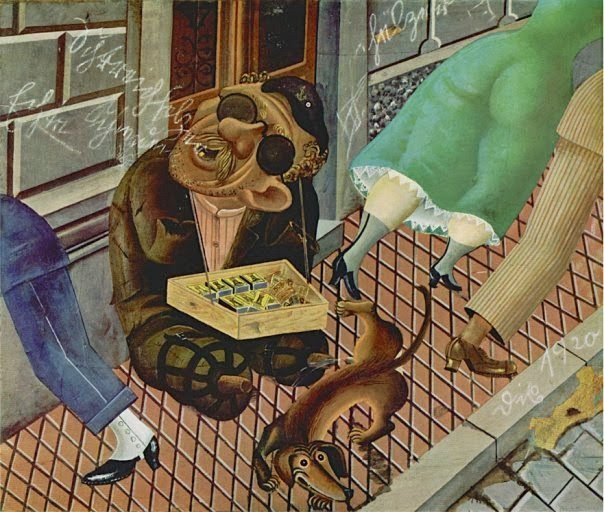

But quickly, one realises that there is a whole industry of media production which supports every step of the process and who are interested in making people believe that they are one of millions, if not billions of universally alike consumers without an enemy, so as to keep providing you with the illusion of catharsis in the false enemy.

Marx identified religion as the central ideology of his time which was both false and a weapon of the oppressors to the proletariat in their place. It does not seem unreasonable to propose that it is now the media which is the new ideology designed to make all believe that they are consumers when in fact they still face the same class struggle, defined by the material conditions of their lives as they always did.

Thus, what one comes to realise is that the true enemy is not someone facing the same struggle within a different culture. What one comes to realise is that in our age it is not a person, but a system of things populated by certain people. No longer does one exist in a proletariat-bourgeoisie or serf-master dichotomy, but rather one exists against a system of thing.

As Marcuse wrote “the society which … undertakes the technological transformation of nature alters the base of domination by gradually replacing personal dependence … with dependence on the objective order of things”

Every time one clicks on a YouTube clip, or uses Facebook, or Twitter, or Netflix “we” are giving ourselves over to an economic enemy which is exploiting us by stealth, by dominating our leisure time and creating a false sense of dependency on a media system. The enemy therefore is not an individual or group of individuals, but it is the system as a whole which has created at ideology which fundamentally undermines the value of truth by telling us that there are no enemies.

However, there are some who profit by that system and others who are exploited by it and therefore we are not all universal consumers. It is still the case that some of us are exploited and other exploiters (even if only unconsciously) and therefore “we” are not everyone.

When all is considered in tandem it becomes evident that we still have enemies although they may now appear in a different light and in a different domain. It is now media, which as the principal weapon of the system of economic oppression and which now forms the central locus for the struggle. It may for the moment appear to many that media forms some neutral space, but even now the veil is beginning to fall off from that false ideology.

As Carl Schmitt said “the newly won neutral domain has become immediately another arena of struggle” To respond a little more directly to the research question posed at the start of this essay, the fact of this ideological lie of universalism which emanates from the media industry and the exploitation committed by the media industry means that there is not an identifiable “neutral domain” at this time, that “we” are not everyone and that therefore we still have enemies.