Nationalist and cosmopolitan, right-wing and libertarian, revolutionary and rooted in tradition. Such was the adventure, led by Gabriele D’Annunzio, in the irredentist Italian (now Croatian) town of Fiume between 1919 and 1920. How many people know what it was all about? Adriano Erriguel explains it all in this great article.

I.

Today it is difficult to admit it, but in its beginnings, Italian fascism did not foreshadow the disastrous course it would eventually take for the history of Europe.

Emerging from chaos as a wave of youth, fascism belonged to a revolutionary era in which, in the face of old problems, new solutions were emerging. At its founding moment, Italian Fascism presented itself as an attitude rather than an ideology, as an aesthetic rather than a doctrine, as an ethic rather than a dogma. And it was the poet, soldier and condottiero Gabriele D’Annunzio who sketched, in the most emphatic way, that possible fascism that could never be, and that ended up giving way to a real fascism which failed to fulfill its initial promises to gallop, in the most obtuse way, towards the abyss.

Poet laureate and war hero, exhibitionist and demagogue, megalomaniac and histrionic, nationalist and cosmopolitan, mystic and amoral, ascetic and hedonist, drug addict and erotomaniac, revolutionary and reactionary, with a talent for eclecticism, recycling and pastiche, the genius precursor of staging and public relations: D’Annunzio was a postmodernist avant la lettre whose obsessions seem astonishingly contemporary. The fire he helped to start would take a long time to die out, but nothing would ever be the same again. Why should we remember this cursed man today?

Perhaps because in a monochord atmosphere of political correctness, tame transgressions and skimmed thinking, figures like his work as a counter-model, and remind us that, after all, imagination can indeed come to power.

Incendiary Years

It was an era of irrepressible vitality that, overloaded with tensions and high-voltage ideas, needed a world war to vent its contradictions. The few years between 1900 and 1914 saw an extraordinary fire in art and literature, in thought and ideology, which soon spread throughout the world. One of the epicenters of that fire was Italy—more specifically the axis between Florence and Milan—the place where “the dream of a radiant future that would emerge after having purified the past and the present by iron and fire” was kindled. This artistic-literary pyromania of art and literature, of thought and ideology, soon spread to the whole world.

This artistic-literary pyromania was nourished, in its deepest strata, by a philosophical and cultural revolution, carefully incubated during the second half of the nineteenth century—an ideological gale that lashed out against the rationalist positivism of the triumphant bourgeois civilization. Against the tabulation of existence by economics and reason, this new vitalism claimed the power of the irrational, of instinct and the subconscious and against liberal optimism; in a world pacified by progress, it opposed a tragic and heroic conception of existence. It was in this intellectual climate that a challenge arose which, because of its radical nature, could well be described as a new myth. A myth destined to cut history in two halves.

Three decades ago, the Italian essayist Giorgio Locchi gave the name “suprahumanism” to a current of ideas that found its most complete formulation in the work of Friedrich Nietzsche—on a philosophical level—and in the work of Richard Wagner—on an artistic and mythopoetic level. In its essence, according to Locchi, suprahumanism consisted of “a historically new consciousness, the consciousness of the fateful advent of nihilism, that is—to put it in more modern terminology—of the imminence of the end of history.”

Essentially anti-egalitarian, suprahumanism stood against the ideological currents that shaped two millennia of history: “Christianity as a worldly project, democracy, liberalism, socialism: all currents that belonged to the egalitarian camp.” The profound aspiration of suprahumanism—which for Locchi was nothing more than the emergence of the European pre-Christian unconscious into the realm of consciousness—consisted in proceeding to a re-foundation of history through the advent of a new man. With a method of action—nihilism as the only way out of nihilism, a positive nihilism that drank the cup to the dregs and made a clean slate to build, on the ruins and with the ruins, the new world.

More than an organized current, suprahumanism took shape as a European intellectual climate that permeated, to varying degrees, the thought, literature and art of the early twentieth century, with France as the ideological laboratory and Italy as the theater of all experiments. In the Italian ferment of those years, revolutionary syndicalists, avant-gardists, anarchists, and nationalists agitated, and all bore, to varying degrees, the suprahumanist imprint. But the undisputed protagonist among all the would-be incendiaries was the Futurist movement.

Futurism was the first truly global avant-garde, not only in the geographical sense but also insofar as it conveyed an aspiration to totality. (Futurism was present in Russia (Mayakovsky), in Portugal (Pessoa), in Belgium, in Argentina or in the Anglo-Saxon world with the foundation in London of the Vorticist movement by Ezra Pound and Wyndham Lewis.) Far from being limited to being an artistic proposal, Futurism extended to thought, literature, music, cinema, urban planning, architecture, design, fashion, advertising and politics. Futurism carried “the euphoria for the world of technology, machines and speed” and used “a new synthetic, metallic, syncopated language.” It did not disdain “the apology of violence and war; it exalted race understood as lineage—not as vulgar racism—and above all as the promise of a future suprahumanity.” Its enemies were the bourgeoisie, romanticism, tradition, the clergy, families; everything old, in short. Futurism was the avant-garde par excellence, the radical theorization of a pyromaniac will. Something that seemed to be, in principle, at the antipodes of D’Annunzio.

At the height of the avant-garde and the outbreak of the First World War, Gabriele D’Annunzio—celebrated throughout Italy as Il Vate—was the peninsula’s most famous writer, for many its leading poet after Dante. But for the Futurists, his style—abounding in modernist, decadentist and symbolist mannerisms, in ornate and eighteenth-century rhetoric—could be considered in its own right as the language of that mausoleum they wanted to set on fire.

But between the Futurists and D’Annunzio it was more a matter of love and hate. In the wake of Byron, Il Vate thought that a poet could also be a hero. At the outbreak of the World War, and displaying the versatility he had already shown in his literary career, he turned from a decadent poet into a combatant poet. And he invested himself with a new mission, that of exemplifying the suprahumanist ideal and its ultimate aspiration—the overcoming of the bourgeois world and the arrival of a “new man” who would embody a new ethic of action. The style is the man. Few figures as ready as his to symbolize the new times.

Gathering Flowers for a Massacre

Death is here… as beautiful as life, intoxicating, full of promise, transfiguring (Gabriele D’Annunzio).

Today it is difficult to understand the suicidal impulse of a civilization that, at the height of its power, organized its own holocaust. The outbreak of the First World War was celebrated as an outpouring of vitality, as catharsis and moral regeneration. The warmongering enthusiasm knew no boundaries of ideology or class, and artists and intellectuals all over Europe were ready to become the voice of the nation. No other voice sang of war with such rapture as that of D’Annunzio. No other oratory prepared so many compatriots, by the glory and seduction of words, to kill and die. No other apostle of war was so eager to assume, in his own flesh, the effects of what he preached.

When Italy announced its entry into war, Il Vate was at the height of his glory. Celebrated throughout Europe, surrounded by luxury and swarmed by women, everything invited him to contemplate the war from a comfortable distance. But at the age of 52 he enlisted in the Lanciere di Novara (Novara Lancers), a unit with which he was to take part in dozens of actions. The army, aware of the propaganda potential of his figure, allowed him to serve in a way that would have the greatest public impact. And it allowed him to use what would be his most lethal weapon—the word.

During four years of war, D’Annunzio spoke and spoke. He spoke in the trenches and in the rearguards, in the airfields and on the naval bases, at mass funerals and at the time of the attacks. His speeches were evocative and magnetic, intended to win not the intellect but the emotions. In them, the crudest physical miseries were adorned with a nimbus of glory; the combatants were heroes and martyrs—as noble as the heroes of classical antiquity or the legions of Rome—and the war was a heroic symphony in which his words rang out like “hypnotic waves of language: blood, death, love, pain, victory, martyrdom, fire, Italy, blood, death.”

Although he knew firsthand the horror of the carnage, he continued to preach his faith in “the purifying virtues of war and telling the troops that they were superhuman.” He spoke of flags flying over the sky of Italy, of rivers full of corpses, of the earth thirsting for blood. He did not disguise the atrocity of the war—which he described as the tortures Dante never imagined for his Inferno—but to the soldiers he told them that their sacrifice had meaning, and he praised them in a way they would never have recognized themselves; and he repeated that the blood of the martyrs cried out for more blood, and that only by blood would Greater Italy be redeemed. He told the soldiers that their sacrifice had a meaning, and he praised them in a way they would never have recognized themselves, and he repeated that the blood of the martyrs cried out for more blood, and that only by blood would Greater Italy be redeemed. He said to the soldiers that their sacrifice had a meaning.

An apologetics of the slaughter, that is; a hundred years later, difficult to digest. Did he believe it?

That is not the question. And it seems insufficient to be satisfied here with a “non-anachronistic” reading, or to limit oneself to pointing out that “that was the language of the time.” Perhaps it would be more appropriate to proceed to a reversal of perspective. Or to a different reading, in a suprahumanist key.

War as an Inner Experience

The reputation that D’Annunzio acquired during the war is due more to his deeds than to his words. Far from being a “paper soldier” he wasted no occasion to put his life in danger, and over the course of three years he came to fight on land, at sea and in the air. With a forerunning talent for publicity, he knew that small acts of terrorism had more psychological force than massive attacks, and he specialized in suicide actions—aerial and naval according to futurist canons—with symbolic value and media impact. He flew numerous times over the Alps—at a time when that was extraordinary—to bomb the enemy, occasionally with propaganda sheets. And when the Austrians put a price on his head he led a suicide raid, in a torpedo boat with a handful of men, against the enemy port of Buccari. (In the bombing, he included hollow rubber shells containing lyrical messages. He later celebrated this fact—known as La beffa di Buccari, “The Joke of Buccari,” in a famous ballad: “La Canzone del Carnaro” [“The Song of Carnaro,” “The Thirty of Buccari”]: “We are thirty men on board/ thirty-one counting Death”).

In one of his aerial missions, he lost the sight of one eye and partially that of the other, which he hid for a month in order to continue flying. Finally, he had to remain immobilized for several months to save his sight.

Lying on his back, and between pain and nightmares, he composed his poem “Notturno” (“Nocturn”). The prospect of blindness was for him an occasion for overcoming, rather than dejection. He confessed himself happy in the greatness of his loss—the blind in action were considered as the aristocracy of the wounded—and he enjoyed the sharpening of his senses of hearing and smell. If he was to be believed, that sense of happiness would never leave him throughout the war. The real D’Annunzio.

The true D’Annunzio reveals himself, more than in his patriotic trumpeting, in his correspondence and in his diaries. They reveal his suprahumanist attitude towards war. If anything is striking in his notes, it is the “constant fluctuation between the dreadful and the pastoral.” Everything becomes for him an object of celebration, even the most insignificant details—from explosions and bayonet attacks to the glow of a dragonfly in the mud, or the fleeting appearance of a woodpecker among the burnt trees. If he is to be believed, D’Annunzio was happy in the midst of hunger, thirst, extreme cold, wounds and bombardments, because his omnivorous enthusiasm for life could cope with it all, because all of it was but one and the same—the manifestation of that life which he consumed with voluptuous enthusiasm. What was war, if not a hole in ordinary life through which something higher manifested itself: “Life as it should be, and which passes before us, Life—in Ernst Jünger’s words—as supreme effort, will to fight and to dominate.”

The parallelism between D’Annunzio and Jünger is not casual; both manifest a common suprahumanist attitude. The same eagerness for experience, the same defiance of chance, the same aesthetic concern, the same absence of moralism. In contrast, in the case of the Prussian—apart from the acerbic objectivity of his style—the practical absence of any patriotic note. But it is also possible to think that in D’Annunzio the nationalist prosopopoeia was not the grain, but the chaff. A weapon of war like many others. It is possible to think that what was essential for him was that discipline of suffering of which Nietzsche spoke, that Amor fati which is nothing more than a great Yes to life in all its rawness.

More than of warmongering exaltation, it is a philosophical option, very different from the moralizing and pitiful posture of other writers. When Wilfred Owen, Heinrich Maria Remarque or Ernest Hemingway denounce and condemn war, they are undoubtedly right, but they do not fail to underline a truism. It happens that they experience war from the horrified sensibility of modern man. But when Ernst Jünger writes: “those who have only felt and retained the bitterness of their own suffering, instead of recognizing in it [war] the sign of a high affirmation, they have lived as slaves, they have had no Inner Life, but only a pure and sadly material existence,” what he is doing is expressing that immemorial sensibility that considers the spirit to be everything. “All is vanity in this world,” Jünger continues, “only emotion is eternal. Only to very few men is it given to be able to sink in its sublime futility.” Amor fati. “Moral” language is no good here. If anything, the language of the Iliad.

Another interesting element is D’Annunzio’s use of historical time. The new/old dichotomy, a recurring theme in his thought, would reach full expression in his war notes. Always on the lookout for historical analogies, “every infantryman reminded him of some episode of the glorious past, every exhausted peasant of an intrepid Venetian sailor, of a Roman legionary, of a medieval knight, of some martial saint recreated in a Renaissance painting. His vision of Italy’s glorious past covered the horrible conflict with a theatrical veil and surrounded the excrement, the garbage and the heaps of dead with glamour.” For the poet from Pescara the weaponry might be modern, but the men who wielded it—the young recruits he likened to mythical heroes or archetypes—belonged to a timeless tradition.

This confusion of past and present illustrates in its own way an element that Giorgio Locchi associated with the suprahumanist mentality: the “non-linear” conception of time, the constant presence of the past as a dimension that is within the present, alongside the dimension of the future. It is the revolutionary idea—as opposed to linear conceptions, whether “progressive” or “cyclical”—of the three-dimensionality of historical time: in every human consciousness “the past is nothing other than the project to which man conforms his historical action, a project that he tries to realize according to the image that he forms of himself and that he strives to incarnate. The past appears then not as something dead, but as a prefiguration of the future.”

Locchi associated this “nostalgia for the future” to the “spherical” image of time sketched in Thus Spake Zarathustra, as well as to one of the meanings channeled by the Nietzschean myth of the Eternal Return. Confusion of past and future, nostalgia for the origins and utopia of the future: the suprahumanist conception of time—felt in a surely unconscious way by D’Annunzio and many others—foregrounds man’s freedom from all determinism, because the past to which to be linked is always an object of choice in the present, as well as an object of changing interpretation. The present moment “is never a point, but a crossroads; each present instant actualizes the totality of the past and empowers the totality of the future.” Thus, the past is never an inert datum; and when it manifests itself in the future it does so in an ever new, ever unknown form.

Hughes-Hallett notes that “war brought D’Annunzio peace.” He had found a transcendental “third dimension” of being, beyond life and death. To set out on a dangerous mission was for him to reach an ecstasy comparable to that of the great mystics. The war brought him “adventure, purpose, a cohort of brave young comrades to love with a love beyond that which is devoted to women, a form of fame, new and virile, and the intoxication of living in constant mortal danger.” He ended the war recognized as a hero and a heroic man.

He ended the war recognized as a hero and covered with decorations. And then he and many like him—those recruits whom he compared to the mythical heroes of the past—had to return to their homes, to their workshops, to their marriages of convenience, to the monotony of their villages.

Farewell to Arms?

The victorious revolution will come. But it will not be made by beautiful souls, like yours, it will be made by sergeants and poets (Margherita Sarfatti, in the film, The Young Mussolini, 1993).

When on March 23, 1919 a hodgepodge of Futurists, former Arditi (Italian Army Storm Troopers), revolutionary trade unionists and former Socialists founded the first Fasci di Combattimento in Milan’s Holy Sepulchre Square, no one really knew what was going to come out of it all. Its visible head was the former sergeant Benito Mussolini, a maneuvering and possibilist politician recently expelled from the Italian Socialist Party. Mussolini claimed that the Fascists would avoid ideological dogmatism: “We allow ourselves the luxury of being aristocratic and democratic, conservative and progressive, reactionary and revolutionary, of accepting the law and going beyond it.” And he added that “above all we are supporters of freedom. We want freedom for all, even for our enemies.” The first Fascist program, visibly leaning to the left, took up the intellectual heritage of revolutionary syndicalism.

Seen in perspective there is no doubt today that historical fascism was a complete ideological phenomenon. But in its beginnings, it seemed to be the fruit of great improvisation. Mussolini proclaimed then: fascism is action and is born of a need for action. In the first place it took up many of the urgent aspirations of the “lost generation” which had fought the war, and which considered that the state of Italy—a poor and backward country, with chronic inequalities, without social security, with a victory “mutilated” by the Allies and heading for civil war—made a return to the era of the bourgeois parties and their electoral dances unthinkable. But in a deeper sense—as the historian Zeev Sternhell points out—before becoming a political force, fascism was a cultural phenomenon, an extreme manifestation—though not the only possible one—of a much broader phenomenon.

(We are adhering here to a strict analysis of Italian fascism, which excludes Nazism. Sternhell, the Israeli historian points out: “Fascism can in no way be identified with Nazism…. Both ideologies differ in a fundamental matter: biological determinism, racism in its most extreme sense… war against the Jews…. Racism is not one of the necessary conditions for the existence of fascism. A general theory that wants to encompass fascism and Nazism would always clash with that aspect of the problem. In fact, such a theory is not possible.”)

The most immediate intellectual antecedent of fascism was the revision of Marxism undertaken by revolutionary syndicalism, a revision in an anti-materialist sense. What these heretics of Marxism challenged in the doctrine was its scientific pretension, its undervaluation of psychological and national factors, its view of socialism as a mere rational form of economic organization. Another of their motivations was their disenchantment with the value of the proletariat as a revolutionary force; the proletarians were normally refractory to anything that did not affect their material interests, that is, to their aspiration to become petty bourgeois. Something that the first Fascists noted, just as they also noted that, between socialism and the proletariat, the relationship was merely circumstantial. From which it was deduced that the revolution was no longer a question of a single social class… which in turn broke the dogma of the class struggle. The revolution became, then, a national task, and nationalism its guiding thread.

But what revolution? A revolution with purely economic motives was insufficient for the political culture that was taking shape—a communitarian, anti-individualist and anti-rationalist political culture that aspired to remedy the social disintegration caused by modernity. In fact, in economics, fascism manifested itself as possibilist and declared that it wanted to take advantage of the best of capitalism and industrial progress, the essential thing being that the economic sphere should always remain subordinate to politics. The underlying question was different.

The essential thing—following Zeev Sternhell—was “to establish a heroic civilization on the ruins of a creepingly materialistic civilization, to mold a new, activist and dynamic man.” The original fascism exhibited a modern character, and its futuristic aesthetics pricked the imagination of intellectuals—which explains its attraction to the youth—as well as preaching that an elite is not a category defined by the place it occupies in the production process, but the expression of a state of mind—the aristocracy forged in the trenches was proof of this. And from Marxism it took the idea of violence as an instrument of change. Someone once defined fascism as our evil of the century: an expression that evokes an aspiration to overcome the bourgeois world. More than a doctrinal corpus, the original fascism was a nebula, a rupturing force of unprecedented character that aspired to the construction of a “solution of total change.”

Giorgio Locchi distinguished the mythical, ideological and synthetic phases as archetypal phases of historical trends. Thus, in the case of egalitarian thought, its “mythical” phase would correspond to Christian ecumenism, the “ideological” phase to the disintegration caused by the Protestant Reformation and the emergence of various philosophies and parties, and the “synthetic” phase to doctrines with scientific and universal pretensions (Marxism, ideology of “human rights”).

What was happening—to put it in Locchian terms—was that the suprahumanist principle was passing, in an accelerated manner, from its mythical phase to its ideological and political phase. On the ideological plane the so-called German Conservative Revolution was one of its manifestations. And on the political phase, Mussolini’s fascism was the offshoot that made its fortune. But it was not the only one.

And this is where D’Annunzio comes in.

II.

When D’Annunzio arrived in Fiume on September 12, 1919, the Platonic dream of the poet-prince came to life two millennia late. A gale of Dionysian liberation was unleashed on the Adriatic city, a Nietzschean riot in which politics and mysticism, utopia and violence, revolution and Dada went hand in hand. A magical moment, a bacchanal of dreamers, a suprahumanist and heroic symphony.

The Road to the Rubicon

At the beginning of 1919, Mussolini was only a budding political leader, while D’Annunzio was the most celebrated man in Italy. With the war ending in a “mutilated victory”—the Allies ignored the territorial promises made to Italy—the country was plunged into a spiral of political and social chaos. And then many of those who expected a “strongman” to take the reins began to look to D’Annunzio. For his part, the soldier-poet was discovering how difficult it was for him to live without the war, and like many other Italians he was ruminating on his bitterness at the betrayal of the Allies.

“Your victory will not be mutilated”—wrote D’Annunzio in October 1918. A slogan that made his fortune (like so many others he coined) and that was music to the ears of all those who awaited a new call to arms. Italy was overflowing with men accustomed to violence and who, instead of receiving a hero’s welcome, were treated as unwelcome guests if not savage beasts, doomed to unemployment and the insults of the agitators of a budding Bolshevik revolution. Prominent among these men were the Arditi, the elite soldiers, fiercely undisciplined, accustomed to hand-to-hand fighting and fighting with daggers and grenades, dressed in black uniforms and with tufts of hair sometimes as long as horses’ manes—the dandies of war. Their flag was black and their anthem, “Giovinezza” (Youth). Everyone looked up to D’Annunzio as a symbol, and some of them began to call themselves “Dannunzians.” A war hero and a homecoming army—a fateful conjunction for any civilian government. The authorities began to fear D’Annunzio. The Rubicon had never been truly forgotten in Italy.

The soldier-poet began to multiply his public appearances, to mock the government that had accepted the humiliation of Versailles, to incite the Italians to reject their authorities. In a very short time, he found himself at the center of all the conspiracies, and all the opposition groups began to use his name. With the Fascists he kept his distance. D’Annunzio considered them as “vulgar imitators, potentially useful, but unfortunately brutal and primitive in their way of thinking.” And among all those who turned their gaze to D’Annunzio were the Italian communities on the Adriatic coast who hoped to be “redeemed” by their incorporation into the mother country. D’Annunzio, for his part, promised them that he would be with them “to the end.”

The city of Fiume, the main port on the Adriatic, had a majority Italian population that in October 1918 demanded its incorporation into Italy. But the Allies meeting in Versailles placed the city under international administration. The city then became a symbol for all Italian nationalists, and groups of former Arditi, shouting, “Fiume or death,” began to form the “Legion of Fiume” ready to “liberate” the city. And in the midst of a spiral of violence, the Italians of Fiume offered D’Annunzio the leadership of the city.

The poet-soldier had found his Rubicon. And his new incarnation—that of condottiero.

Fiume was a Party

“The contagion of greatness is the greatest danger for anyone living in Fiume, a contagious madness, which has permeated everyone” (The Bishop of Fiume, in an interview).

When on September 12, 1919, D’Annunzio arrived in Fiume in a Fiat 501, he surely did not know that he was starting one of the most extravagant experiments in the political history of the West: the Platonic dream of the poet-prince was coming to life two millennia late. A gale of Dionysian liberation was unleashed on the Adriatic city, a Nietzschean riot in which politics and mysticism, utopia and violence, revolution and Dada went hand-in-hand. The era of show-politics had begun, and D’Annunzio raised the curtain.

The Fiume era has been described as a microcosm of the modern political world—everything was prefigured there, everything was experienced there, we are all largely its heirs. A magical moment, a bacchanal of dreamers, a suprahumanist and heroic symphony in which a society hungry for wonders—galvanized by war, jaded by the insipidity of a century of positivism—met a leader at its height and seconded, to the rhythm of multicolored parades and rapturous crowds, his visionary Caesar’s chimeras.

The political trajectory of the city during those sixteen months was, unsurprisingly, erratic. The first program—annexation to Italy—was simple and realistic, but it was shipwrecked in a sea of indecision and diplomatic gambits. The second program was of a subversive nature—to provoke the spark that would unleash a revolution in Italy. But there was a third program, uncontrollable and radical—Fiume as a first step, not towards a Greater Italy, but towards a new world order.

A program that gained strength as the prospect of incorporation into Italy dissipated under pressure from the Allies and the Italian government’s indecision. Prompted by the syndicalist revolutionaries who surrounded D’Annunzio, the “Constitution of Fiume” (the Carnaro Charter) is the most interesting aspect of Fiume’s legacy, insofar as it represents an original contribution to political theory. The Carnaro Charter contained pioneering elements—the limitation of the (until then sacrosanct) right to private property, the complete equality of women, secularism in schools, absolute freedom of worship, a complete system of social security, measures of direct democracy, a mechanism of continuous renewal of leadership and a system of corporations or representation by sections of the community—an idea that would become a fortune. According to his biographer Michael A. Ledeen, D’Annunzio’s government—composed of very heterogeneous elements—was one of the first to practice a kind of “politics of consensus,” according to the idea that the various conflicting interests could be “sublimated” within a newfangled movement. The essential point was that the new order should be based on the personal qualities of heroism and genius, rather than on the traditional criteria of wealth, inheritance and power. The ultimate goal—basically suprahumanist—was none other than the alloy of a new type of man.

The Carnaro Charter contained surrealistic touches such as designating “Music” as the fundamental principle of the State. But the most original—the most specifically Dannunzian—was the inclusion of “an elaborate system of mass celebrations and rituals, designed to guarantee a high level of political awareness and enthusiasm among the citizens.” In Fiume, D’Annunzio (now referred to as “the Commander”) began experimenting with a new medium, creating “works of art in which the materials were columns of men, showers of flowers, fireworks, electrifying music—a genre that would later be developed and reworked over two decades in Rome, Moscow and Berlin.” The commander inaugurated a new form of leadership based on direct communication between the leader and the masses, a kind of daily plebiscite in which the crowds, gathered before his balcony, answered his questions and seconded his invectives. The whole ritual of fascism was already there: the uniforms, the banners, the cult of martyrs, the torchlight parades, the black shirts, the glorification of virility and youth, the communion between the leader and the people, the arm-in-arm salute, the battle cry: Eia, Eia, Alalá! Hughes-Hallett points out that D’Annunzio was never a fascist but that fascism was unmistakably Dannunzian. Someone wrote that, under fascism, D’Annunzio was the victim of the greatest plagiarism in history.

Another pioneering element was the creation of an anti-imperialist League of Nations: the “League of Fiume,” a project of alliance of all the oppressed nations that developed the concept of world revolution and of “proletarian nation” theorized by Michels, and which aspired to bring together from the Irish Sinn Fein to the Arab and Indian nationalists. Some want to see the Commander as a prophet of Third Worldism, although it would be more correct to see here “the first appearance of the theme of the rights of peoples.” The Allied powers began to be alarmed. Fiume’s enterprise was losing its nationalist character and accentuating its revolutionary content.

Make Love and War!

“Youth, Youth, Springtime of Beauty!” (Song of the Arditi)

A State ruled by a poet and with creativity turned into a civic obligation—it was not strange that cultural life acquired an anti-conventional bias. The Constitution was under the invocation of the “Tenth Muse,” the Muse, according to D’Annunzio, “of emerging communities and peoples in genesis… the Muse of Energy,” which in the new century would lead the imagination to power. To make life a work of art. In the Fiume of 1919, public life became a twenty-four-hour performance in which “politics became poetry and poetry sensuality, and in which a political meeting could end in a dance and the dance in an orgy. To be young and to be passionate was an obligation.” An atmosphere of sexual freedom and free love, unusual for the time, spread among the local population and the newcomers. The sexual revolution was beginning. This was what the new “Prince of Youth,” one-eyed and fifty-six years old, wanted.

No wonder the city became a magnetic pole for the whole brotherhood of idealists, rebels and romantics that swarmed the world. A Free-for-All Country where proto-fascists and internationalist revolutionaries rubbed shoulders without anyone thinking of something as vulgar as “entering into dialogue.” A countercultural laboratory in which a variety of groups sprouted, such as “Yoga” (inspired by Hinduism and the Bhagavad-Gita), the “Lotos Castaños” (proto-hippies in favor of a return to nature), the “Lotos Rojos” (defenders of Dionysian sex), ecologists, nudists, Dadaists and other specimens of various kinds. The psychedelic component was ensured by a generous circulation of drugs under the tolerant gaze of the Commander, a more or less occasional consumer of white powder. The 1960s began in Fiume. But unlike the Californian hippies, the Commander’s hippies were ready not only to make love, but also to make war.

Meanwhile, Rome looked at Fiume with a mixture of dismay and dread. In the words of the Italian socialists, “Fiume was being transformed into a brothel, a refuge for criminals and prostitutes.” The truth is that everyone went to Fiume—soldiers, adventurers, revolutionaries, intellectuals, allied spies, cosmopolitan artists, neo-pagan poets, bohemians with their heads in the clouds, the futurist Marinetti, the inventor Marconi, the orchestra conductor Toscanini. Eloquence and dandyism proliferated; the Commander’s personality was contagious. Decorations, uniforms, titles, hymns and ceremonies for everyone! The ornamental style was de rigueur. And in turn, the new visitors were becoming more and more marginal—runaway minors, deserters, criminals and other people with unfinished business with the justice system. Many of these elements were recruited to form the Commander’s corps guard: the “Legion Disperata,” with its glittering uniforms. D’Annunzio observed his Arditi eating lamb on the beaches, in their fantastic uniforms gleaming in the flame light, and compared them to Achilles and his myrmidons back at their camp in front of Troy. It is that electrifying mixture of archaism and futurism, so characteristic of the suprahumanist sensibility. It sounded so old, and yet it was so new.

Pressed by its international commitments, the government of Rome decreed a blockade against Fiume, and the city found a method to ensure its subsistence—piracy. Organized by a former Italian aviation ace, Guido Keller, Fiume’s ships came to seize any vessel transiting between the Strait of Messina and Venice. And every capture made by the Uscocchi—so named by D’Annunzio after the Adriatic pirates of the 16th century—was greeted in the city as a feast. Illicit activities extended to kidnapping—a commando from Fiume captured an Italian general passing through Trieste—and to expeditions to requisition supplies in neighboring territories, and also to symbolic occupations of other nearby cities. The Commander had his motto, Ne me frego (something like, “I don’t give a damn”) embroidered on a flag that he hung over his bed. Fiume was an outlaw state, what today we would call a hooligan state. His biographer points out that D’Annunzio, like a new Peter Pan, had built a “Never Never Land, a space freed from cause-effect relationships where lost children could forever enjoy their dangerous adventures without being bothered by common sense.”

But the problem of childhood is that it ends, and the time for adults arrives. The Treaty of Rapallo, signed in November 1920, established the Italian-Yugoslav borders and reached a compromise on Fiume. D’Annunzio was isolated, and even Mussolini’s fascists withdrew their support. After an intervention by the Italian Navy and the resistance of a handful of Arditi—which resulted in several dozen deaths—D’Annunzio was forced to leave Fiume at the end of December 1920. In a farewell ceremony his last cry was: “Long live love!”

The poet had concluded his revolution. It was the turn of the former sergeant.

Fascism without D’Annunzio

As the years went by, a Mussolini already in power would celebrate Gabriele D’Annunzio as the “John the Baptist of Fascism.” Becoming a legend, the poet would spend his last two decades secluded in his mansion of El Vittoriale on the shores of Lake Garda, where Mussolini would occasionally come to have his portrait taken with him.

Today D’Annunzio is considered a figure of the Regime, but the truth is that he was never a member of the Fascist Party and his relations with the Duce were much more ambivalent than one might think. In private, Mussolini referred to D’Annunzio as “a cavity, to be removed or covered with gold,” and he also referred to “misunderstood Fiumism” as a synonym of an anarchist attitude and thus unreliable. In fact, both men regarded each other with suspicion: Mussolini considered D’Annunzio too influential and unpredictable, and the latter refrained from expressly supporting the Duce. In fact, the poet had recommended to his Arditi to stay away from any political formation, although many would end up in fascism and some in the extreme left or even in Spain in the International Brigades. The only occasions on which D’Annunzio tried to influence Mussolini politically were to advise him to stay well away from Hitler (“that ferocious clown,” “that gummed-up and ignoble face”).

The poet-soldier died in 1938 in his Vittoriale mansion, in an atmosphere as baroque as it was claustrophobic, surrounded by Italian and German spies. With his death a whole epoch disappeared—that of the dawn of that fascism that could not be. The real fascism took up the staging and liturgy of Fiume, but emptied them of freedom and transformed them into a bureaucratized choreography at the service of a project that led Italy to catastrophe. The story is well known. However, some things are often overlooked.

It is often overlooked that this early fascism was part of an avant-garde, sophisticated and pluralistic cultural climate, very different from the obtuse provincialism that characterized the Nazis and their völkisch kitsch. In fact, the cultural pluralism of Fascist Italy—a country where there was practically no intellectual exodus whatsoever—has no parallel with the dirigisme imposed on culture in the Nazi era. Scholars such as Renzo de Felice or Julien Freund have contrasted the optimistic and “Mediterranean” character of fascism—with its tendency to exalt life in a certain spirit of moderation—with the somber, tragic and catastrophic character of Nazism, with its Germanic penchant for Raggnarök. The anti-dogmatic—even artistic and bohemian—character of that first fascism could also be highlighted, as opposed to the “scientific” pretensions of Nazi dogmatics, based on biological racism and social Darwinism.

It should be added that the first fascism had no hint of anti-Semitism, but rather the opposite: many Jews were early fascists and even held important positions, such as the publicist Margaritta Sarfati, Jewish lover of the Duce and prima donna of the cultural life of the regime. In fact, the foreign policy of the regime maintained frequent contacts with the Zionist movement. And after Hitler came to power, eminent Jewish exiles found a welcome in Italy.

It is also overlooked that after the “march on Rome” in 1922 Mussolini stood before Parliament and won a large vote of confidence from the non-fascist majority. One tends to forget that the violence of the fascist squads, while very true, was not unique to fascism—that was the political language in much of Europe. And in Italy it was fascism, better organized, that finally prevailed. It is also omitted that fascism collaborated with the socialists and other opposition forces, and that it won a majority of votes in the 1924 elections. Only then, after the brutal assassination of the socialist deputy Matteoti and the refusal of the opposition to remain in Parliament, did the Fascist henchmen gain the upper hand and the dictatorship was institutionalized.

In reality, 1924 marks the beginning of the decline. The following years were those of the great achievements of the regime—the construction of a social State, the great public works and the modernization of the country. These achievements won the support of a large part of the population. But fascism was already mortally wounded. By betraying that promise of 1919 in the Piazza del Santo Sepulcro in Milan (“We want freedom for all, even for our enemies”), fascism was transformed into a self-satisfied and self-indulgent bureaucracy, and Mussolini gradually withdrew from reality to enclose himself in a megalomania that turned out to be disastrous.

Even so, for some years fascism promoted a policy favoring peace and international cooperation, as evidenced by the Lateran Agreements in 1929 and the disarmament proposals in the League of Nations in 1932. In relation to Nazi Germany, there is something that is also often forgotten—Mussolini was the driving force behind the so-called “Stresa Front,” a diplomatic initiative that in April 1935, together with France and Great Britain, tried to guarantee the independence of Austria and respect for the Treaty of Versailles, and therefore to stop Hitler when it was still possible to do so. Two months later, in June 1935, Great Britain signed with Nazi Germany a Naval Agreement which was the first violation of that Treaty. Mussolini was left alone.

The isolation was consummated with the invasion of Abyssinia and the sanctions imposed on Italy, which forced Mussolini into an alliance with Hitler. From then on, a prisoner of a mixture of fear and fascination for the German dictator, the Duce was dragged into the abyss. In 1938, he even fell into the abjection of importing the anti-Semitic legislation of the Third Reich.

Would another, less dictatorial and more “Dannunzian” course have been possible? Mussolini, unlike Hitler, never had absolute control over the Party, and within fascism there was always a line against the Nazis and in favor of an understanding with France and Great Britain. Its main figure was the Minister of Aviation, Italo Balbo, war hero and early squadronist, the true prototype of the “new man” exalted by fascism. But a jealous Mussolini appointed him Governor of Libya to remove him from the centers of power. There he died in 1940, in an unclear airplane accident. The last remnants of the fascist opposition were liquidated in 1944 in the Verona Trial, with former Foreign Minister Galeazzo Ciano and other hierarchs executed at the behest of the Germans.

A Democratic Fascism?

Almost a hundred years later, D’Annunzio and his adventure in Fiume still raise questions. One is particularly provocative—could a democratic fascism have been possible?

A question that only has the value we want to give to history—fiction. Because history is what it is, and it cannot be changed. To speak of “democratic fascism” is today an oxymoron, and that seems undeniable. However, too often we take refuge in intellectually comfortable and morally irreproachable positions, and that makes it difficult to understand certain phenomena. In this case, the nature of fascism. The classical Marxist interpretation of fascism as a defensive instrument of Capital condemns itself to understand nothing, and leaves unexplained the wide adhesion obtained by a system that was only extirpated by war, a war in which the Marxists allied themselves with—capitalism. This interpretation has long since been superseded, and today it tends to be admitted that, as Zeev Sternhell points out, fascism was an extreme manifestation of a much more comprehensive and broader phenomenon—that which Giorgio Locchi called suprahumanism—and as such is an integral part of the history of European culture.

D’Annunzio was not a systematic ideologue, but his Promethean and Nietzschean endeavor symbolizes that suprahumanist cultural climate from which fascism sprang. Fiume was a magical and necessarily fleeting moment: one cannot be sublime for twenty years. But Fiume reminds us that history could have been different, and that perhaps that cultural and political rebellion—let’s call it “fascism”—could have been compatible with a greater respect for freedoms, or at least evolve away from the aberrations already known. Of course, then perhaps that would no longer be fascism; it would be something else.

If we do not take into account the cultural phenomenon of suprahumanism, fascism cannot be understood. But this was not its only offshoot. Historically there were two others. The first was an intellectual offshoot of great height, and which continues to speak to the men of our days: the so-called German “conservative revolution.” And the second was a poisonous plant: Nazism. The question that could be raised today is whether this suprahumanist cultural humus is definitively exhausted, or whether it could still give rise to unprecedented derivations. After all—and according to the “spherical” conception of time—history is always open; and when history regenerates itself it does so in an ever new, ever unforeseen way.

Right-Wing Anarchism

“We denounce the lack of taste in parliamentary representation. We recreate ourselves in beauty, in elegance, courtesy and style…. We want to be led by miraculous and fantastic men” (Filippo Tommaso Marinetti).

“The art of commanding consists in not commanding” (Gabriele D’Annunzio).

But the interest in re-examining D’Annunzio goes far beyond the question of the nature of fascism. The poet-soldier prefigures a way of doing politics that is still in force today: the politics of spectacle, the fusion of sacred and profane elements, the intuition that ultimately everything is politics. The Charter of Carnaro is a visionary document, insofar as it takes up concerns, liberties and rights hitherto relegated outside the political sphere, and which in the following decades would become part of modern constitutionalism. Somehow D’Annunzio seemed to hold the key to all that was to follow. We are all to a large extent his heirs, for better and for worse.

That is why it would be a mistake to belittle D’Annunzio as a dilettantish aesthete turned revolutionary. Or to depoliticize him and consider—as his perceptive biographer Michael A. Ledeen seems to point out—that what is important in Fiume is not the content but the style, and that no concrete ideological position emerges from Fiume. Carlos Caballero Jurado is much more correct when he says that: “Fiume was not a piece of land. Fiume was a symbol, a myth, something that perhaps cannot be understood in our days, in an era so refractory to myth and rites. Fiume’s enterprise has more to do with cultural rebellion than with political annexation.” What messages can the man of today draw, not only from Fiume, but from D’Annunzio’s entire trajectory?

In the first place, the idea that the only true revolution is the one that pursues an integral transformation of man. That is to say, the one that is posed first and foremost as a cultural revolution. Something that the revolutionaries of May 1968 seemed to understand well. But what they did not know was that, in reality, almost everything they proposed had already been invented—imagination had already come to power, fifty years earlier, on the Adriatic coast. The great surprise is that the one who so decided—and this is the second great lesson of Fiume—was not a progressive, libertarian and globalist utopian, but a patriot, an elitist practitioner of a heroic ethic. Fiume is the demonstration that ideas such as sexual liberation, ecology, direct democracy, equality between men and women, freedom of conscience and the spirit of celebration can be put forward not only from egalitarian, pacifist, hedonist and feminist positions, but also from aristocratic and differentialist, identitarian and heroic values.

D’Annunzio’s gesture also implies something very current—it was the first cry of rebellion against an American-morphous system that in those years was beginning to extend its tentacles; it is the cry of defense of beauty and spirit against the reign of vulgarity and the empire of the dollar.

D’Annunzio’s gesture was also the surreal and heroic vindication of a political regeneration based on the liberation of the human personality, and a cry of protest against the world of anonymous bureaucrats that was coming upon us.

Fiume is also a demonstration that it is possible to transcend the right-left divide, that transversality is possible. Right-wing values plus left-wing ideas. The first genuinely postmodern synthesis. Fiume is the only known experiment to date of what could be a right-wing anarchism taken to its ultimate consequences.

There is one last question, and that has to do with D’Annunzio’s activity as a preacher and exalter of war. That is something that today seems indefensible to us—although it was not so much so in those years when the war could still be lived as an epic adventure. But today we know that behind that inflamed rhetoric there was no real cause to justify so much sacrifice. And yet…

However, it is possible that those men of inflamed rhetoric, deep down, also knew this. It is quite possible that D’Annunzio and others like him, by distillation of a positive nihilism, knew that in the end patriotism is much better than nothingness. Today we have the Nothing, and certainly we have fewer dead. But it is worth asking whether, compared to those men, we are also more alive because of it.

The era of the incendiary years has submerged in time. The time when sergeants and poets made revolutions has passed. And as they say, bodies were devoured by time, dreams were devoured by history, and history was swallowed up by oblivion. They also say that old warriors never die, that they only fade away physically. After the catastrophe, we are left with the memory of greatness, and of the men who dreamed it.

Adriano Erriguel, from Mexico, is a practicing lawyer and consultant and also a literary critic and essayist in the field of the history of ideas, from a perspective that he insists on calling “metapolitics.” His preferred area of focus is the marginal intellectual currents, alternative and alien to the prevailing ideological consensus. His ambition is to draw up an intellectual cartography of the sources of rebellion that, from an anti-modern or post-modern perspective, confront political correctness and uniform thought. This article appears through the kind courgtesy of El Manifiesto.

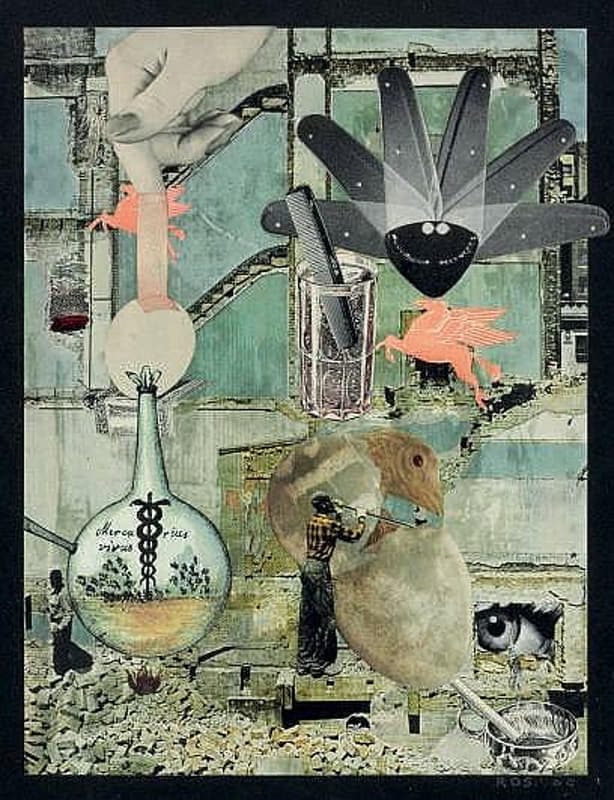

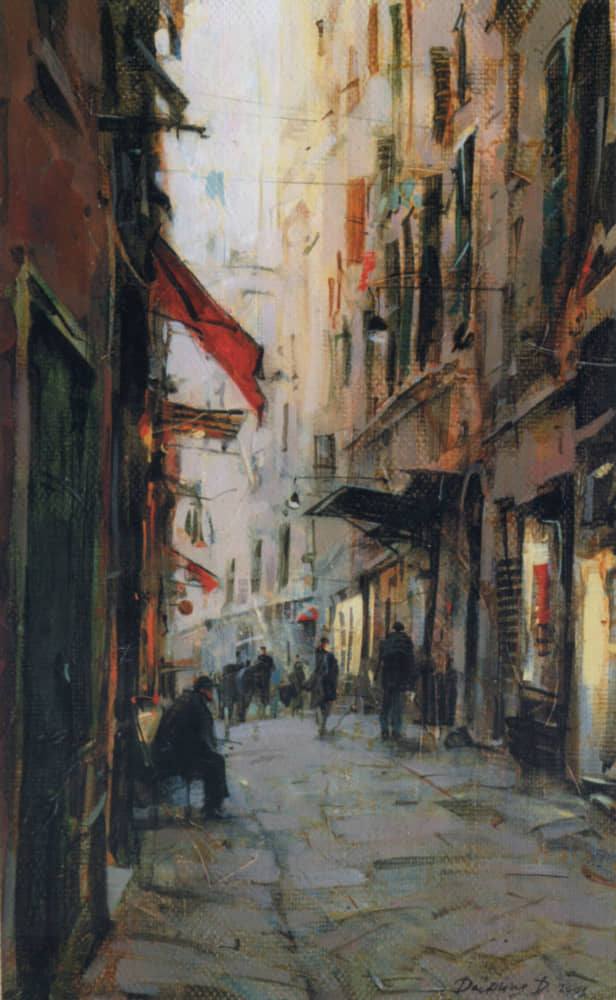

Featured: D’Annunzio in Fiume, ca. 1919-1920.