Not so long ago, when “The State” and the banks appropriated the savings of thousands of Lebanese families, the French press was all abuzz about Lebanon. And then, the Lebanese and their bankrupt country were forgotten.

Between 1915 and 1918, Mount Lebanon was hit by a terrible famine that took away almost a third of its population and left in the Lebanese memory the certainty of the overwhelming responsibility of the Ottoman authorities in the organization and unleashing of what they considered a genocide. For many Lebanese, there is still no doubt that the famine of 1915-1918 was deliberately organized by the Ottoman authorities.

Lebanon has been distinguished from the neighboring provinces of Damascus and Beirut by a long tradition of autonomy. For three centuries, local emirs governed this Ottoman province. Between 1842 and 1860, taking advantage of “dissensions” within the population, the Sublime Porte tried to reinforce its control—without success. In 1860, the Muslim Druze massacred hundreds of Christians. In spite of a muted diplomatic resistance from England, France obtained permission from the European powers to send an expeditionary force to come to the aid of the victims and to restore order. The confessional massacres of the time led to the military intervention of Napoleon III’s troops and to the re-establishment of Lebanese autonomy guaranteed by the five powers, with the establishment of a specific administrative regime—Mount Lebanon would henceforth be directed by a compulsorily Catholic governor, appointed by the Sublime Porte after European agreement.

From 1913, following the coup d’état of Enver Pasha, the Ottoman Empire was governed by a triumvirate of which he was the dominant figure. In April 1915, in the midst of the war, he authorized his Minister of the Interior, Talaat Pasha (the “Turkish Hitler”) to organize the massacre of the Christian peoples of the empire: Assyrians, Pontic Greeks and Armenians. Wikipedia forgets the Lebanese in this sinister list.

For them, the matter was delegated to Jamal Pasha. But the objectives were the same.

“Enver Pasha then delegated Jamal Pasha who was given the job of exterminating Christians in the empire. From then on, he bore the nickname of Jamal Pasha al-Saffah. For this clever and Machiavellian man, there was no question of repeating the mistake of 1860. The sword used in the Armenian, Syriac or Assyrian-Chaldean regions could not be used in Lebanon without taking the risk of a new French landing” (Dr. Amine Jules Iskandar, President of the Syriac Maronite Union, Tur Levnon).

The Armenian precedent leaves little room for doubt as to the real intentions of the Turks. The mass deportation of Armenians from Anatolia coincided with the time when the blockade and repression of Mount Lebanon intensified (March 1915). The same chronology, the same motivations of the executioners—like the regions of eastern Anatolia, the Syrian coast and Mount Lebanon seemed like weak points for the Ottoman defense. Hence the objective of “creating a desert” in these two regions.

The Young Turk leaders had the necessary motive. They were suspicious of these Arabs who were much too Europeanized for their taste. Unlike Armenia and Upper Mesopotamia, Lebanon was closely connected to Europe. It was necessary to isolate it diplomatically and in the media before imposing the food blockade. Jamal Pasha immediately instituted general censorship. Once all communications with the outside world had been cut off, it was time to start.

It began in 1914, with the abolition of the capitulations signed between the Christian powers and the Sublime Porte which guaranteed the security of the Christians of the empire: the autonomy of Mount Lebanon was abolished. Persecutions multiplied: military occupation of the Mountain (November 1914); de facto suppression of its privileges (March 1915); forced appointment of administrators known for their harshness: Jamal Pasha, military governor of Beirut and Mount Lebanon from December 1914, and Ali Munif Bey who replaced Ohannes Pasha. Ali Munif Bey had distinguished himself by his relentless persecution of the Armenians of Adana, his home town. In his Memoirs, (Revue d’Histoire arménienne contemporaine, Tome V, le Liban. Mémoire d’un Gouverneur, 1913-1915, Ohannes Pasha Kouyoumdjian, 2003), Ohannes Pasha denounced Ali Munif Bey’s tactics—in 1915, he formed a Lebanese Red Crescent Committee. Officially, it was to help the Lebanese; in reality it was only a machine to extort donations from them. And then there was the violent repression of the Lebanese elites: in 1915-1916, several notables were sentenced to death for treason and hanged, and two hundred others deported to Anatolia.

The Ottoman Empire’s entry into the war against the Entente powers at the end of October was followed by a blockade of Entente ships on the western side. Set up in November 1914, this ruthless blockade not only in the Mediterranean but also in the Red Sea, (which continued until the autumn of 1918 when the outcome of the war was no longer in doubt) stopped the grain trade in the eastern Mediterranean.

On the eastern side, the land blockade was ordered by Jamal Pasha. Mount Lebanon was very dependent on the surrounding regions for food because of the scarcity of its agricultural land and the density of its population: 100 inhabitants/km2, i.e., ten times more than in the neighboring vilayet of Damascus, which was well provided with arable land (Ohannes Pasha, Memoirs). But in 1914, the food situation in Syria and Lebanon was favorable: the summer harvests had made it possible to build up large stocks.

From November 1914, the price of flour soared. The Lebanese sold their silk cocoons at a low price, then had to mortgage their goods to rich merchants in Beirut or Tripoli. The interest rate on loans soared to 400% the following year.

Visiting Lebanon in February 1916, Enver Pasha was quoted as saying: “We destroyed the Armenians with iron. We will destroy the Lebanese with hunger.”

Which was well on its way.

Practicing a scorched earth policy, the Turks destroyed most of the depots and railway equipment. In 1916, fearing for the army’s supplies, Jamal Pasha requisitioned all wheat, kerosene, beasts of burden, poultry and cattle, wood, and building materials. In 1916, the Ottoman soldiery even attacked the plantations, orchards and forests. The hills of Lebanon were completely stripped under the pretext of supplying coal to the trains. Jamal Pasha forbade the peasants to thresh the wheat before the arrival of a government agent. With the rains, the crops rotted. Many peasants fled to areas beyond the control of the government, so that the authorities were forced to ask soldiers to plow the fields around Damascus.

The Christians, starving and having already sold their furniture and clothes, ended up selling the beams of their houses. The roofs collapsed and families were left homeless with nothing on their bodies. To those who, from Constantinople, pointed out to him that the exclusive use of the means of transport for the benefit of the army risked starving the capital, Enver Pasha replied: “I do not care… about the supply for the population; it will look after itself as best it can. During the Balkan war, the civilians were full while the army was starving. Now it is their turn to fast: I am only concerned about my soldiers.”

The means of transport were thus lacking: the transport of grain through Port Said was not easier. In mid-October 1916, British General Allenby opposed the establishment of a French naval base in Beirut and refused to lift the blockade entirely, prohibiting the outflow of wheat to Lebanon.

The peak of the crisis was reached in 1917-1918. The desperate search for food led to social regression. In March 1918, near Tripoli, two women were arrested for kidnapping and devouring eight girls.

“Living skeletons wandered here and there in the mud and snow. One could hardly tell the living from the dead. The carts dumped in mass graves about a hundred bodies a day in the city of Beirut alone. In these conditions of cold, malnutrition, non-nutrition and absolute lack of hygiene, epidemics took their toll. Typhus, cholera, plague and other diseases of another age added to the misfortunes of the Lebanese. This is where the Ottoman genius proved itself. Pharmacies were robbed, medicines of all kinds were requisitioned, always for the needs of the army. The Sublime Porte needed doctors to treat its soldiers on the front, so they mobilized doctors from all the towns and villages. The cruelty of the invader had no limit. Ottoman-style corruption was in full swing. Even some Christians participated in it. The governor of Lebanon, Ohannes Kouyoumjian, who was far too honest and honest, was replaced by Ali Mounif. The latter arrived in Lebanon “penniless and left with two million gold francs” (Amine Jules Iskandar).

The shortage of wheat during the spring of 1916 was also due to the sending of grain to Arabia in order to keep the allegiance of the Bedouin tribes of the Hejaz, as the Arab revolt of Sharif Hussein began. The famine did not spare Syria, starting with Damascus, although it was close to the rich agricultural lands of the Hauran. There, as in Lebanon, the local population was sacrificed to the Turkish army and civil servants, the only beneficiaries of rationing. They were immolated on the altar of the strategic objectives of the Ottoman Empire.

The window still open to Europe, specific to Lebanon, was the Church: the Catholic missionaries, their monasteries and their schools. All their properties and places were requisitioned, transformed into barracks or military depots. Expelled, the missionaries could no longer serve as witnesses and observers. What remained were the Maronite bishops, but also the Romanian (Greek Orthodox) and Melkite bishops. The most active of them were then exiled; some Maronite bishops were even court-martialed and hanged. Lazarists, Jesuits, Daughters of Charity were still present in Lebanon in 1914. In November, most of them were expelled and their places ransacked. Inside the Mountain, the Lebanese members of the Catholic congregations managed to keep some missions open to relieve the suffering of the population. These had to be abandoned under pressure from the Turks in 1916.

In the spring of 1916, French diplomats estimated the number of victims in the mountains and on the coast at more than 80,000 (more than 50,000 in the mountains alone).

The Lebanese emigration mobilized; and in June of the same year, in New York, a Committee of support for the Syrian Mount Lebanon was formed. The poet Khalil Gibran joined it. He dedicated two poems to the Lebanese people: “Dead are mt People.” Of course, there has been much discussion about this committed poetry. However, the text remains quite vague in its poetic evocation of the “invisible snakes” responsible for this “tragedy beyond words.” The snakes were quite visible and the poet did not risk much in New York.

The Jesuits denounced the crime as coming “on the heels of the Armenian genocide.” The French ambassador in Cairo, Jules-Albert Defrance, who was close to the Lebanese community in Egypt, wrote to Aristide Briand at the French Ministry of Foreign Affairs. The latter then shared the information and alarming news with Camille Barrère, his ambassador in Rome, and also with the Holy See, with Washington (on May 16, 1916) and with the very Christian king of Spain. The atrocities are described in all these letters. All came to the same conclusion: a military intervention in the Levant would be fatal for the Christians of Lebanon. It would push the Ottomans to speed up their work and, perhaps, to put them to the sword. As for the food aid, it was systematically confiscated and diverted by the Ottomans.

On the Perseus website, there is an edifying article by Yann Bouyrat, “Une crise alimentaire provoquée? La famine au Liban (1915-1918).” The author is an associate professor and doctor of history, a researcher at the CEMMC in Bordeaux, and a lecturer at the Université Catholique de l’Ouest. “The article was validated by the reading committee of the CTHS in the context of the publication of the proceedings of the 139th National Congress of Historical and Scientific Societies, a symposium held in Rennes in 2013.”

The main thrust of the article is to mitigate the responsibility of the Turks and to minimize the role of France. Thus, the testimonies against the Turks are contradicted by other sources. First, the Spanish consul, who never believed in any “genocide by hunger” of the Lebanese population; a text from the Patriarch of the Maronites, found in the military archives, which clearly defends Jamal Pasha and underlines “his eager courtesy” and “the salutary effects of his generosity in providing food for the poor.” Meager evidence all. In the diplomats’ reports, Enver Pasha is presented as a criminal.

As for Ohannes Pasha, he was Armenian, which makes him “subjective.”

For Mr. Bouyrat, the ban on the export of cereals from Aleppo and Damascus to the mountains and the coast should be seen as a security measure to avoid the building up of cereal stocks on the coast, which could have served a possible invading army. And it could also be explained by the speculative madness of a certain number of unscrupulous local grain merchants. Monopolizing the grain market, the Aleppo merchants drove up prices, preventing the Beirut traders from recouping their expenses. This is undoubtedly true. But how does this diminish the responsibility of the Ottomans?

For this “specialist” in humanitarian intervention, “the human toll of the famine is difficult to establish with certainty.”

Really? For the Mountain alone, the losses reached at least 120,000 people—that is to say a third of the population. According to Dr. Jules Iskandar, out of a Lebanese population of 450,000 people, about 220,000 died. And half of the survivors went into exile. “We are,” he says, “the descendants of the remaining small quarter.”

The government in Paris, sensitive to the fate of the Syrian-Lebanese population, had considered on several occasions a partial lifting of the blockade. It had to give up in the face of London’s veto. Warned of the seriousness of the situation in the Mountain by Mgr Joseph Darian, Archbishop of Alexandria and spokesman for the Maronite Patriarch, Aristide Briand, then President of the Council, had successively asked two neutral powers (the United States in June, then Spain in July 1916), to intervene with the Porte so that it would authorize the sending of international humanitarian aid to Lebanon. In exchange, France agreed to allow the passage of ships chartered for relief. Here again, the intransigence of England forbade it. As well as the bad faith of the Turkish government, which did everything to hinder the action of the American and Spanish action committees.

The rescue of Lebanon began in 1918-1919; and the action was considerably amplified after the arrival of the French army in Beirut. When the first detachments landed in the city on October 7, 1918, the situation was catastrophic. The only aid brought to the population came from the British navy and remained insignificant: 100 tons of cereals, 50 tons at the disposal of the city of Beirut and 50 for the Mountain. At the same time, the monthly needs of Lebanon and the coast were estimated at over 2,000 tons.

At the end of October, Clemenceau’s intervention enabled France to obtain an end to the obstacles to the circulation of cereals. The arrival of all this aid in November quickly had positive effects: it brought down the price of foodstuffs and forced speculators to sell their stocks.

What is taught in Lebanese schools today?

Lebanese children are taught that the famine that decimated a third to half of their people at the time was due to the unfortunate coincidence of disparate factors: the Allied sea blockade, the Ottoman land blockade and the locust invasion.

But even more serious, according to Dr. Amine Jules Iskandar: two hundred thousand disarmed victims whose only crime was to be Christian—and not a museum, not a monument, not a public square, not a national day, not a mention in the history books. Greater Lebanon preferred them to the forty martyrs of the Place des Canons that now bears their name: their multi-faith origins better satisfied the image sought by the young state.

Ancient Lebanon had such respect for its martyrs that it dedicated to them the highest peak in the country: Qornet Sodé (in Syriac: the Summit of the Martyrs). The name has now become the meaningless Arabic, Qornet al-Sawda (Black Summit). In order to build this Greater Lebanon, now in ruins, the historical Lebanon was sacrificed, which should have been the soul of the new state and not considered a hindrance.

Was it necessary to abandon its Syriac language and the ancient Christian cultural base that was supported by it? Was it necessary to conceal the blood of the martyrs by erasing the black page of this famine, if not planned, at least wanted and organized?

We must leave the historian Yann Bouyrat to his academic ambitions and privilege the testimony of those who carry in their living memory the infinite grief of the survivors and their frightening lucidity:

“We are the descendants of the quarter that survived and remained in Lebanon. And from this group, three quarters also emigrated. So, we are only one quarter of the quarter. Let us be conscious and modest in the face of all this legacy for which we are responsible today. The genocide of the Christians of the East, “Tsekhaspanutyan” Ցեղասպանություն (genocide) for the Armenians, “The Sayfo” (the sword) for the Christians of Upper Mesopotamia and “The Kafno” (famine) for the Christians of Lebanon, is a duty of memory. One cannot murder a people twice; first by death, then by silence and oblivion. It is a national duty to be taken into account at the level of state, religious and cultural institutions.”

He is right.

And his testimony weighs more heavily in the balance of responsibility than Mr. Bouyrat’s work on questions of humanitarian interference. The millions of victims weigh more in the scales of justice than diplomatic issues. The honor of France, which was involved in this drama, was saved by all those who behaved with courage and humanity:

“The Syrian island of Arwad (ouad in French) was in the hands of the French, under the command of Albert Trabaud. The aid from the Lebanese diaspora was then brought to the island and transported by night to the Lebanese coast. The first part of the journey was done by boat, while the second part was completed by swimming. The gold was handed over to the envoys of the patriarch of the Maronites. The sums collected in Bkerke were then used to buy quantities of food to be distributed to the people in order to limit the carnage as much as possible…. Albert Trabaud contributed to the survival of our ancestors, there is still a street in Achrafieh named after him? For how long?” (Jules Iskandar)

A people without memory is a people without a future. Today’s Lebanon is a country in ruins that survives only thanks to a Christian diaspora assimilated wherever it exists, industrious and with a high degree of education. It knows that on it depends the survival of this small country with an ancient history that gave the alphabet to the European world and inaugurated the history of the Mediterranean and its civilization.

And today?

Today, the world history of infamy continues through the scandal of the Latchine corridor: 150,000 Armenians deprived of everything by the Azeris in defiance of international rights.

But can anyone tell us when an Islamic state has respected such rights?

In a few years, eminent academics with titles will write about the question of humanitarian interference in Nagorno-Karabakh, wondering about the number of victims and the difficulty of establishing the number with certainty.

In the meantime, men, women and children are dying. Christians.

In French schools, grade five students are taught that there were “contacts” between Islam and Christianity in the Mediterranean and that Islam was a brilliant Arab-Muslim civilization to which we owe the transfer of all Greek science.

We believe in order to dream.

Marion Duvauchel is a historian of religions and holds a PhD in philosophy. She has published widely, and has taught in various places, including France, Morocco, Qatar, and Cambodia. She is the founder of the Pteah Barang, in Cambodia.

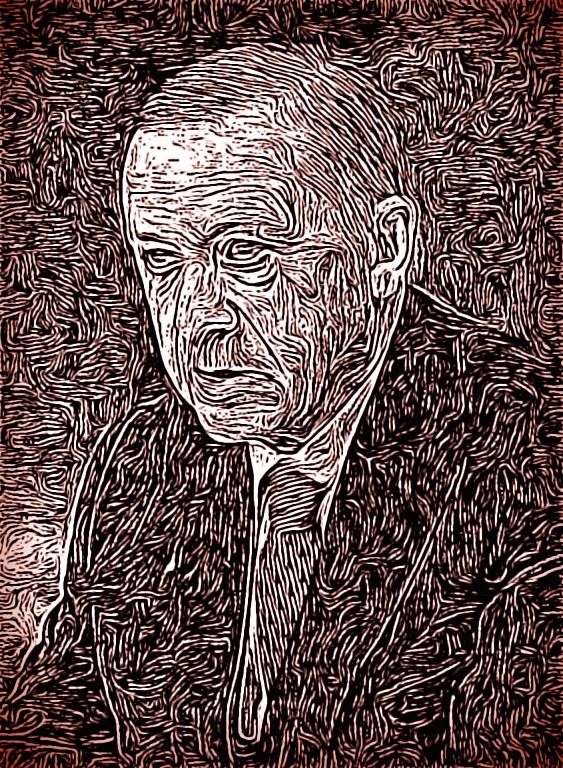

Featured: Starving family in Mount Lebanon, ca. 1915-1918.