Since the fall of the Berlin Wall, socialist-communist historiography is no longer popular. The old Lenino-Trotsko-Marxist manichaeism, inherited from the Enlightenment, has gradually withdrawn from the Western political and cultural scene, leaving room for deconstructionist progressivism, an immanent religion just as deleterious, a mixture of contradictory neo-puritan, communitarian and ethnicist beliefs, such as ultra-feminism, multiculturalism, decolonialism, indigenism, immigrationism, the celebration of sexual minorities, Islamo-leftism and the blissful worship of nature.

This new version of humanitarian morality is defended by large multinationals and powerful lobbies or NGOs, with the complacency, even the blessing, of the majority of the political-economical-media elites. The “new righteous,” modern inquisitors, guardians of political correctness, claim, as in the past, to monopolize the interpretation of the meaning of history, to embody goodness, reason, progress, science, humanitarian and democratic values.

The earlier marginalized, excluded, declared reactionary, obscurantist and obstacles to the establishment of the socialist society (in the name of the radiant future and the communist paradise), independent historians and nonconformists, opposed to the unilateral reading of history and to the utopia of the anthropological transformation, which is the prelude to the enslavement of the people, are again subjected to sectarianism, intolerance, contempt and hate. Intellectual terrorism does not vary much in its methods and arguments – in yesteryear, to criticize communism was to play into the hands of the bourgeoisie and fascism. Today, to criticize the deconstructionism of the globalist doxa is to play into the hands of populism, racism and fascism.

Nazi Crimes And Communist Crimes: Double Standards

“Those who cannot remember the past,” said George Santayana, “are condemned to repeat it” (Life and Reason, 1905). The crimes of the National Socialist regime have been quantified and unreservedly condemned, both morally and legally. But there is still a great deal of work to be done to make people aware of the crimes committed in the name of communism; to assess their number and to condemn them in the strongest terms. The terrible human toll of socialism and Marxism is said to belong to history, but it is still astonishingly underestimated, passed over in silence, or even excused or absolved.

Communist sympathizers, and their former comrades-in-arms, whether camouflaged or out in the open, are in the habit of claiming that the criminal practice of Hitler’s National Socialism stems from the perversity of his ideology, whereas that of communism would only have originated from the deviation, the denaturation, the deviation of a generous and humanist inspiration. No one denies the appalling Nazi genocide except a few small groups without influence, or deranged minds.

But on the other hand, communists and their fellow travelers can deny the exterminationist character of the Marxist theoretical-practical apparatus, can express themselves freely on major media, can be heard and even considered sincere and idealist, as long as they solemnly declare, “I do not recognize myself in the crimes of certain communist countries.” Recognized as a crime in the case of Nazism (5 to 12 million dead victims), communist negationism (50 to 100 million dead victims) is tolerated, accepted, even justified. While there should be no difference between the victims of violence, there is a macabre hierarchy for them – and despite everything.

When on September 19, 2019, the European Parliament adopted a Resolution on “the importance of historical memory for the future of Europe,” condemning the crimes committed by the Nazi and Communist regimes, the Communist, and more broadly socialist-Marxist, press was indignant and denounced the “manipulation of history.” The text of the Resolution was described as “confusing,” “contradictory,” “unacceptable,” a “monument to relativism,” a “gross simplification of reality,” a “falsification” and “revisionism.”

According to these negationists, self-proclaimed “progressives,” there are good and bad victims: The amalgam between socialism-Marxism and national socialism must be censured and denounced – but the equivalence must be accepted and even recommended when it concerns Nazism and fascism. According to them, there is uniqueness in the case of fascism, but not in the case of communism. The facts do not matter. The Italian fascists caused between 600 and 700 casualties among the social-communist militants and suffered the same number of casualties in their own ranks.

The Mussolini regime executed 9 Slovenian terrorists from 1922 to 1940 and 17 more in 1943, when the civil war started. The number of political prisoners in fascist Italy never exceeded two thousand. The deadly record of Italian fascism is obviously light years different than that of Nazism. But the degree of bad faith, Manicheism, sectarianism and hatred by the communists and their socialist-Marxist fellow travelers is limitless.

Why should the obsession with leveling equality be any less morbid and mortifying than the mania for hierarchizing races? Why should class (or even religious) genocide be less condemnable when in fact it has been even more devastating and deadly than race genocide? These questions remain unanswered; and the pseudo-arguments and pretexts of the communists (“one cannot compare what is not comparable;” “one cannot put on the same level, in full equivalence, Nazism which is destructive, and communism which is regenerative;” “one cannot confuse Stalin, Lenin, Trotsky, Castro, Mao and Pol Pot”) only fool those who want to be fooled.

The Cultural Hegemony Of The PCF And Its Fellow Travelers: 1945-1968

The intellectual and academic circles of Western Europe have always been more or less under the sway of politics. But there is a gap between the usual partial and fragmentary influence and the vast enterprise of nucleation and cultural quasi-domination of Marxism during the years 1945-1989. In the case of France, the hold on cultural life of orthodox communist militants and sympathizers (themselves often manipulated by Soviet agents), and then of the various post-Soviet leftists, was (and let’s not mince our words) – major if not exceptional until the fall of the Berlin Wall. Moscow communism was only brought to coexist with Maoist, Trotskyite, Castro and libertarian communisms from 1965-1968. There were of course, from the aftermath of the Second World War, brilliant anti-communist or anti-Marxist figures, such as Raymond Aron, Thierry Maulnier, Bertrand de Jouvenel or Albert Camus; but for more than forty years the pluralism of French cultural life was, to use two euphemisms, “framed and limited.”

The Marxist or crypto-Marxist inquisitors watched over and locked down the debate. Whoever wanted to make a career in the world of letters or academia had to give pledges to Marxist thought, and above all to avoid clashing head-on with the powerful guardians of the camp of the good.

Examples abound of victims of Marxist and leftist censorship, who saw their intellectual or academic careers compromised, hindered and sometimes broken – the sociologist, Jules Monnerot, for having dissected the Marxist revolution and revealed its character as a secular religion (Sociologie du communisme, 1963); the political scientist, Julien Freund, for his defense of realism in politics (L’essence du politique, 1965): the sinologist, Simon Leys, for his unmasking of Maoism (Les habits neufs du président Mao, 1971); the political scientist, Gaston Bouthoul, for his study of the recurrence of the belligerent phenomenon and his criticism of traditional pacifism, which has become the worst enemy of peace (Lettre ouverte aux pacifistes, 1972); the writer, Jean Raspail, for having prophesied the wild and mass immigration (Le camp des saints, 1973); the historian, Pierre Chaunu, and the journalist, Georges Suffert, for having denounced, very early, the right to abortion and the demographic collapse of Europe (La peste blanche. Comment éviter le suicide de l’Occident, 1976); the historian, Reynald Sécher, for having published La Vendée-Vengé. Le génocide franco-français (1986)… and many others.

After the fall of the Berlin Wall, censorship and control took on other forms; but the same deleterious intellectual mores were perpetuated by one-thought and political correctness. We cannot ignore the troubles and career difficulties of a host of academics, such as, the sociologist, Paul Yonnet, for having meticulously analyzed the causes of the French malaise (Voyage au centre du malaise français. L’antiracisme et le roman national, 1993); the specialist in slavery, Olivier Petré Grenouilleau, for having revealed the extent of the Eastern and intra-African slave trade, and not only the Western one (Les Traites négrières. Essai d’histoire globale, 2004); the medievalist Sylvain Gouguenheim, for destroying the myth of a West that would never have existed without Islam (Aristote au Mont-Saint-Michel, 2008), etc. The list of pariahs, banished and marginalized, intellectuals, academics or journalists, is long, very long.

The benevolence, indulgence, connivance and complicity of a large part of the Western cultural and media circles towards Marxist socialism and communist abominations are part of a tradition that is already more than a century old. “There are none so blind as those who do not want to see.” In the 1920s, the edifying testimonies of numerous exiles were known, especially of the hundreds of cultural and scientific personalities, banished, expelled and threatened with being shot, if they returned to the USSR at Lenin’s personal instigation.

These intellectuals, many of them among the most prominent of the Russian intelligentsia, such as Sergei Bulgakov, Nikolai Berdyaev, Nikolay Lossky, Ivan Ilyin, Georges Florovsky, Semyon Frank or Pitirim Sorokin, were not hostile to the revolution as the GPU claimed, but opposed Lenin’s extreme and violent approach. In particular, they reproached Lenin, and this was especially true of the members of the Committee for Aid to the Hungry, for not taking the necessary measures to curb the terrible famine of 1921-1922. Slander, defamation, silence or oblivion were the lot of these first victims of the Leninist purges who, no doubt because of their notoriety, escaped death in the concentration and forced labor camps, created by Trotsky and Lenin, as early as June and August 1918, to lock up “kulaks, priests, White Guards and other dubious elements.”

In 1935, Boris Souvarine published his biography of Stalin (Stalin, A Critical Survey of Bolshevism), which dismantled “in the name of socialism and communism” the lies of Soviet “pseudo-communism.” In 1936, Gide denounced, in his book, Return From the USSR, the vices and defects of a system that he had defended until then. The result – les Amis de l’Union soviétique (the Friends of the Soviet Union) declared him a traitor and an agent of the Gestapo.

Then, in the aftermath of the Spanish Civil War (1936-1939), there were the instructive testimonies of former communist political commissars, such as, Arthur Koestler, or former members of POUM (anti-Stalinist Marxist Unification Workers’ Party), such as, George Orwell; (the members of the POUM were anti-Stalinist Marxists and not “Trotskyists” according to the accusation of Stalinist propaganda), who had been persecuted and murdered by the torturers of “orthodox communism,” during the Spanish war, as had been anarchist leaders. Among these official Stalinists, the political commissar, Artur London (the future author of the book, The Confession, which Costa-Gavras would bring to the screen) had shown an unquestionable zeal in the persecution of “deviationists.” Ironically, he was also accused of being an “internal enemy” and “a Trotskyite” during the Prague trial (1952).

One of the main heads of Soviet military intelligence in Western Europe, Walter G. Krivitsky, who moved to the West in October 1937, also provided a particularly valuable testimony on the democratic fiction of the various Popular Fronts, the action of the Comintern in the West and its relationship with the GPU. He was violently attacked by the American and European left in 1939, when he published two books on Stalin’s methods (In Stalin’s Secret Service and I was Stalin’s Agent, 1940), and finally was reported to have committed a suicide, in a Washington hotel in 1941 (though most likely killed by soviet agents). The testimonies of communists, who had fled to the West, and those of ex-international brigadists, who had survived the Spanish War, followed one another at a rapid pace, but the reaction of the socialist-Marxist left was always the same – insults, shrugs, skepticism and visceral hostility. As for the intellectuals of the non-communist left, they were conspicuous by their absence.

The manipulation of history by the PCF and its fellow travelers was almost total for decades. The PCF had collaborated for almost two years with the German National Socialist regime (from August 23, 1939 to June 22, 1941) under the German-Soviet Pact (of August 23, 1939), which was finally broken only by the will of Germany.

The PCF mandated Denise Ginollin and Maurice Tréand (between June and August 1940), to negotiate with the German authorities the re-publication of the newspaper, L’Humanité and the legalization of the party. The secretary general of the PCF, Maurice Thorez (head of the party from 1930 to 1964), was condemned for desertion; he was exiled to Moscow on November 8, 1939, and was not to return to France until November 27, 1944, six months after the D-Day landings, and after having been amnestied by De Gaulle. But of this dark truth, nothing was said, nothing was known. Thorez was even presented by the PCF as a proven Resistance fighter, an authentic maverick. The PCF claimed to have called for resistance as early as July 10, 1940, and proclaimed itself the party of the “75,000 shot,” when in fact only 4,500 were shot, and not all of them were communists. The same PCF praised for years ad nauseam the alleged managerial qualities of communist mayors.

The Kravchenko affair broke out at the end of the 1940s, when this Soviet diplomat, who had taken refuge in the United States, published in France, J’ai choisi la liberté (1947) – I Chose Freedom: The Personal and Political Life of a Soviet Official, a book in which he made startling revelations about the collectivization of agriculture, the size of the Soviet Gulag camps, and the exploitation of prisoners as slaves. Described as a defector and deserter, Kravchenko was immediately denounced as a spy by the USSR, by the sister communist parties and by their numerous fellow travelers. The weekly Les lettres françaises, a newspaper close to the PCF, accused him of being a disinformer and an agent of the United States. This was followed by a defamation trial in which the Communists put so-called “character witnesses” on the stand, former Resistance fighters, such as, Frédéric Joliot-Curie and Emmanuel d’Astier de la Vigerie. Kravchenko finally won his case in 1949… but died of a bullet to the head in 1966.

Sartre And Beauvoir: Two Famous Fellow Travelers

After the Liberation, Jean-Paul Sartre, who had become a fellow traveler of the PCF and an intellectual icon of the Marxist left, managed to make people believe that he had escaped from a stalag. The reality, however, was far less glowing – he had been released, most likely through the personal intervention of Pierre Drieu la Rochelle. After his release, Sartre once again became a quiet teacher in Parisian high schools (Pasteur and then Condorcet). But neither he nor his companion, Simone de Beauvoir, were ever members of the Resistance. On the contrary, Sartre wrote at least two articles in the collaborationist magazine, Comoedia (in 1941 and 1944); and Beauvoir, who was dismissed by National Education for a sinister case of lesbianism whose victim was a young teenager, got a job at Radio-Vichy, where she delivered twelve broadcasts, in early 1944, shortly before the D-Day landings. But this secret was well kept. (See Jean-Pierre Besse and Claude Pennetier, La négociation secrète, 2006; Jean-Marc Berlière and Franck Liaigre, L’affaire Guy Môquet. Enquête sur une mystification officielle, 2009 and Liquider les traîtres. La face cachée du PCF (1941-1943), 2007; and Gilbert Joseph, Une si douce Occupation… Simone de Beauvoir et Jean-Paul Sartre (1940-1944), 1991 and Michel Onfray, Les consciences réfractaires, 2013).

At Sartre’s request, the manager of the magazine Les Temps modernes, Francis Jeanson, wrote a spiteful review of The Rebel by Albert Camus in 1952. Camus made the unforgivable mistake of attacking Marxist mythology by claiming to be a member of the anarchist and anarcho-syndicalist tradition. A servile opportunist, Sartre explained at that time: “Communism must be judged on its intentions and not on its acts.” On his return from the USSR in 1954, he asserted: “The Soviet citizen has…complete freedom of criticism.” He went even further, not hesitating to say during an interview for Les Temps modernes (1965): “Every anti-communist is a dog.” Admirer of the dictatorship of Fidel Castro at the beginning of the 1960s, he deviated from the Soviet line only to endorse the Maoist cause, after May 1968.

“Last but not least,” as the English say, this friend of the “suitcase carriers” [left-wing intellectuals and artists supporting and channeling funds to the FLN activists], and agents of the Algerian FLN, was among the “progressive” Parisian intellectuals who defended pedophilia in 1970. The libertarian, Michel Onfray, one of the few honest and courageous intellectuals of his generation, has listed the most prominent members of this group. In addition to the names of Jean-Paul Sartre and Daniel Cohn-Bendit, there were Louis Althusser, Louis Aragon, Roland Barthes, Simone de Beauvoir, Jean-Louis Bory, Pascal Bruckner, Gilles Deleuze, Jacques Derrida, Françoise Dolto, Jean-Pierre Faye, Alain Finkielkraut, André Glucksmann, Félix Guattari, Daniel Guérin, Guy Hocquenghem, Bernard Kouchner, Jack Lang, Jean-François Lyotard, Gabriel Maztneff, Alain Robbe-Grillet, Philippe Sollers, etc. (See Michel Onfray, La nef des fous. Des nouvelles du Bas-Empire, 2021).

Twenty years later (March 1990), invited to Bernard Pivot‘s program, Apostrophes, broadcast live on Antenne 2, Gabriel Matzneff presented, in front of a complaisant program director, one of his books relating his pedophile loves. The Canadian novelist Denise Bombardier was the only one to speak out on the set. She had to endure that day the sarcasm and mockery, and later the slander and conspiracy of silence of the cream of the Parisian intelligentsia. The pedophile epidemic, or fad, was then affecting the most unexpected circles on both the left and the right. The Church, which “promised eternal damnation to pedophiles,” was mocked and castigated. It had not yet made its complete aggiornamento. The “literary talent” and the “existential freedom” of “L’Ange Gabriel” (sic) (Maztneff), a worthy disciple of the Marquis de Sade and Gilles de Rais, was surprisingly appreciated and even admired by some of the principal theorists of the New Right.

Even a veiled criticism earned an impudent person the title of backward puritan, old-fashioned and frustrated. Fortunately, pedophilia was not “democratized” like drugs, but it would be no less than thirty years before the first cases of pedo-criminality, involving the French National Education system, the sports world and the Church, broke out. The Sauvé report on sexual abuse in the Church of France was not be published until October 2021. Olivier Duhamel, advisor to the presidents of the Constitutional Council, former member of the European Parliament of the PS, president of the National Foundation of Political Sciences and model hierarch of the French Republic, was only forced to resign in April 2021, after an investigation for rape and sexual assault on his minor stepson.

Sartre was accustomed to legitimizing ultra-violence – faithful in this to Vladimir Ilitch Lenin – but his companion, Simone de Beauvoir, was not to be outdone. Michel Onfray gives these few edifying words of the philosopher, in an anthology which deserve to be quoted in its entirety, these few edifying words of the philosopher: “Any revolution requires from those who undertake it the sacrifice of a generation, of a community.” And again: “One will sacrifice the men of today to those of tomorrow, because the present appears as the factor which it is necessary to transcend towards freedom.” (See Michel Onfray, Les consciences réfractaires. Contre-histoire de la philosophie t.9, 2013, p.374).

This is an era already long gone that could be considered as dead and buried, if a number of rabid and unyielding people did not still gloss over, not without explicit or implicit approval, the most vomitory remarks of the “Thénardier of philosophy.” To quote only one example, the communist, Alain Badiou, professor emeritus at the École normale supérieure, wrote not so long ago, thanks to the complacency of the newspaper, Le Monde, these words that one could believe to have come out of the pen of Fouquier-Tinville or Dzerzhinsky, but which are part of the pure Marxist rhetoric of characterization of the adversary: “And why on earth, if they are real enemies, would I be forbidden to insult them? To compare them to vultures, jackals, bitches, headless linnets, and even to rats, vipers, lecherous or not, even hyenas, typists or not?” (Le Monde, July 24, 2008).

Sartre did not fail, of course, to visit the leader of the German terrorist organization, the Red Army Faction, Andreas Baader (in 1972), nor to support the Khmer Rouge until their victory in 1975. Weakened and ill, he seemed to have finally become aware of the need to save all threatened lives, including those of his adversaries (the boat people) – but not long before he died.

Communists, Leftists And Other Useful Idiots: A Shared Hegemony

In the period following the events of May 1968, and despite the decline of the PCF, the hold of socialism-Marxism on people’s minds remained impressive. For the Catholic Church, since the early 1960s, it was no longer a question of anathema or condemnation of “real socialism” or communism, but only of dialogue and peace. The role of Pope John Paul II (and Lech Walesa’s Polish trade union Solidarnosc) was important if not decisive in the collapse of the communist system, but this should not hide the fact that a significant number of Catholic intellectuals eagerly accepted, and some even as early as 1936, the “helping hand” policy of the PCF. At the Liberation, the Resistance fighter, André Mandouze, (who later became actively involved with the Algerian FLN), called for “taking the outstretched hand of the Communists.” Emmanuel Mounier, founder of the monthly personalistic magazine Esprit, said in a July 1947 issue that he had agreed “to graft Christian hope onto the living areas of communist hope.”

A good number of Catholic fellow travelers found affinities in the humanitarianism of the PCF and the values of the Gospel. Liberation theology, which was very popular in South America, developed from 1968 onwards and withered away in the 1970s and 1980s, after the official warnings of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith (1984). But it has nevertheless formed or influenced many clerics and lay people in Europe, many of whom hold important positions in the Church today. From 1972 to 1989, the YCW (Young Catholic Workers) invited to its gatherings only “class” organizations (CGT and CFDT on the trade union level, PCF and PS on the political level). The membership of former YCW members in the PCF was massive. In November 1998, a former YCW activist was even elected head of the Jeunesses Communistes.

Thanks to the strong personality of John Paul II and the firm theological convictions of Benedict XVI, Rome condemned collaboration with the Communists to the end, thus giving the illusion of the Catholic Church’s capacity to resist any form of neo-paganism or immanent morality. But the degradation of Catholicism, which began in the late 1960s, has not been halted, nor has the agony of Christianity as a whole. In 2013, the pontificate of Francis most likely confirmed the marginalization of Catholicism and Christianity as a religion and most likely the end of Christianity as a civilization.

For more than 70 years, until the fall of the Berlin Wall, the testimonies about the political vices and the concentration camp universe of the communist countries did not stop accumulating. After Kravchenko, Souvarine, Koestler and Orwell, there were the clandestine notebooks of the Samizdat, Milovan Djilas with The New Class: An Analysis of the Communist System (1957), Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn with The Gulag Archipelago (1973), and then Sakharov, Bukovsky, Kovalev, Zinoviev, Voinovich, Grossman, etc., and the criticism of totalitarianism by the French “new philosophers” (authors mostly from the Maoist left, such as, Alain Finkielkraut, André Glucksmann, Bernard-Henri Lévy, Pascal Bruckner, Christian Jambet, Guy Lardreau, Jean-Paul Dollé, Gilles Susong, etc.).

From 1975 onwards, the reports of Vietnamese, Chinese, Cambodian and Laotian victims unreservedly denounced the terror, the crimes, the concentration camps, the forced labor and re-education camps. So many irrefutable testimonies, invariably considered suspect, worthless or false by so many pseudo “virtuous consciences,” the supposed guarantors of democracy and “human rights.” To tell the truth about the communist system was seen as playing into the hands of the right, to be an accomplice of fascism. The true or disguised fellow travelers sometimes admitted, in due lip-service, that communism had killed “tens or hundreds of thousands of people, even millions.” But this was not so serious, since it was in the name of “democratic values” and “the happiness of humanity.” After all, the inspiration was generous; and in any case, death of counter-revolutionaries or fascists was a legitimate sacrifice.

In the 1990s, after the dismantling of the USSR, the Soviet archives made available to researchers did not fail to meet serious resistance. According to the Trotskyite historian, Jean-Jacques Marie, long proclaimed “specialist on the USSR,” these Moscow archives had to be “taken with a grain of salt;” they contained only “imaginary revelations,” and could “be used for anything.” Another example is Stephen Koch’s book, Double Lives: Stalin, Willi Münzenberg, and the Seduction of the Intellectuals, published in 1993.(Its French title is, La fin de l’innocence. Les intellectuels d’Occident et la tentation stalinienne. 30 ans de guerre secrète, 1994). This book was significantly reviewed in Le Monde by the journalist Michel Tatu (“Le prétexte Münzenberg”, 20 October 1995). Koch highlighted the major role of the Soviet spy, Willi Münzenberg, and that of his illustrious recruits, in the unprecedented and formidably effective campaign of Communist manipulation that affected all Western intellectual circles until the end of the 1960s. But his book had a crippling flaw – it insisted on the degree of dependence and submission of the various Popular Fronts to Moscow, particularly in the case of the mythical Spanish Popular Front.

From 1981 to 1995, the two presidential terms of François Mitterrand were marked by various economic-financial scandals, but also by several political-cultural polemics that deserve to be recalled here because of their ideological background. The four communist ministers of Mitterrand obviously had only a symbolic place and role, but the cultural ascendancy exercised by Marxist socialism was of a completely different magnitude. A very large number of Socialist Party cadres had been trained in extreme left-wing parties (PCF, PSU or leftist movements). The lack of police zeal under the various socialist governments to put an end to Action Direct terrorism (1979-1987) cannot be explained otherwise.

The beginning of the 1990s was marked by two political-judicial cases – that of the communist Georges Bourdarel and that of the leftist Cesare Battisti. During the Indochina War, Bourdarel had joined the ranks of Ho Chi Minh’s Vietminh and had become a political commissar in Prison Camp No. 113.

According to the numerous testimonies of survivors of this concentration camp reserved for soldiers, he was guilty of torturing French soldiers. The historian Bruno Riondel, recalls in an edifying work, L’effroyable vérité. Communisme, un siècle de tragédies et de complicités (2020), that 278 of the 320 prisoners in the camp, that this French communist directed, died as a result of the treatment they were subjected to.

Bourdarel lived in the USSR and finally returned to France in 1966, under General de Gaulle’s amnesty law of June 18, 1966. Bourdarel was appointed assistant professor at the University of Paris VII, then promoted to senior lecturer and researcher at the CNRS. Several of his former victims (including a former Secretary of State for Veterans) recognized Bourdarel and filed a complaint in court. This was followed by a media-political campaign in his favor, with the support of some forty academics. Not surprisingly, the complaint against him was rejected, including by the European Court of Justice, because of the amnesty law. The Court of Appeals also ruled that the concept of crimes against humanity, as defined by the International Tribunal of Nuremberg, can only be applied to the events of the Second World War.

At the same time (under Mitterrand and Chirac), Cesare Battisti, ex-member of the group, “Prolétaires armés pour le communisme” (“Armed Proletarians for Communism”), and about 300 other Italian far-left terrorists, were given protection by the French government. Battisti was wanted by the Italian judiciary for committing several assassinations, but extradition was periodically denied, despite the fact that Italy is an EU country. Battisti was complacently portrayed by the mainstream media as a “man of letters,” and was supported, among others, personally by Mrs. Mitterrand, who did not hide her fondness for Fidel Castro’s dictatorship.

This wide political and journalistic network asked for Cesare Battisti “the indulgence due to the purity of his cause.” Thus, for fourteen years (1990-2004), he was able to enjoy, for ideological reasons, the protection of the authorities. His escape to Mexico was even facilitated by the French secret services. Protected in Brazil by President Lula, he was extradited to Italy after Bolsonaro came to power. On March 25, 2019, after admitting his responsibility in four assassinations, he declared before the Italian justice “to have deceived the intellectuals and politicians of the left who supported him.” No comment!

Another highly significant fact: under the impetus of two right-wing men, the president of the Republic Jacques Chirac and the president of the National Assembly Philippe Séguin, on December 5, 1996, on the occasion of the vote for an amendment to a finance law, the French deputies voted unanimously, minus one abstention, for an amendment granting “combatant status” to “Frenchmen who took an effective part in fighting alongside the Spanish Republican Army between July 17, 1936 and February 27, 1939.” One detail does not seem to have troubled them: the International Brigades, to which these Frenchmen belonged, had been created on Stalin’s express orders. The so-called “volunteers of freedom” or “of democracy” were in fact a real army of Stalin in Spain. The vast majority were members of the Communist Party, and the minority were “fellow travelers” belonging to left-wing parties.

From 1994, the new masters of the daily, Le Monde, a “progressive” newspaper called “the leading newspaper,” were Alain Minc, Jean-Marie Colombani and Edwy Plenel. Minc had the reputation of being an opportunist, a businessman and a globalist (he supported, in turn, Mitterrand, Balladur, Jospin, Bayrou, Sarkozy, Juppé and Macron). Jean-Marie Colombani, a socialist, supported Lionel Jospin and Ségolène Royale in the presidential elections. As for Plenel, former editor of the Trotskyite militant magazine Rouge, who became a journalist at Le Monde, he was known and well-regarded for his investigations and his methods similar to those used by a police informant. This journalist “with deep Trotskyist roots” (according to Colombani), was editorial director of Le Monde from 1996 to 2004.

In 2003, the accusations made by Pierre Péan and Philippe Cohen in their book La face cachée du Monde: du contrepouvoir aux abus de pouvoir (2003), led to a crisis for the daily newspaper and the end of this Troika. At the turn of the 21st century, the drift of the French left finally led to a real ideological fracture. In the years 2005-2010, the Islamo-leftism of Plenel and his friends – a strange combination of anti-capitalist radicalism, rejection of traditional secularism, praise for the dominant-dominated/exploited logic, hatred of French identity, Islamophilia and anti-Semitism (anti-Zionism being here only its cover) – constituted the main bridge between the Trotskyists and the political supporters of Islam.

The Polemics Around The Black Book Of Communism

In 1997, nine years after the fall of the Berlin Wall, and three years after the new editorial board of Le Monde, Le livre noire du communisme. Crimes, terreur, repression (The Black Book of Communism) was published. This book, brought out by a group of academics, most of them from the extreme left, intended to take stock of the crimes of communism.

In his introduction, the author, Stéphane Courtois, gives a figure approaching 100 million deaths; and, in a direct attack on all conventionalism, makes a “polemical” comparison between the macabre counts of communism and Nazism.

The press of the left and the extreme left was indignant and protested. The Quinzaine littéraire of the former Trotskyite, Maurice Nadeau, L’Humanité of the PCF and Rouge of the Trotskyite theoretician, Daniel Bensaïd, were at the forefront. But they were also backed up by Le Monde and its subsidiary Le Monde diplomatique, where the pen of the communist, Gilles Perrault, was furious.

The historians who went to war against Le livre noir were all Marxist militants or ex-militants, such as, Pierre Vidal-Naquet, ex-member of the PSU, Annette Wieviorka, ex-Maoist, Annie Lacroix Riz, Jean-Jacques Becker, as well as, Madeleine Rebérioux, Marxist-Leninists, Jean-Jacques Marie, Pierre Broué, Alain Brossat, Denis Berger, Trotskyists or Trotskytizers, along with the American, Arch Getty, a pro-Stalinist revisionist (an avowed admirer of the works of the advocate of restalinization, Iuri Zhuykov, who is in the tradition of Western apologists for Stalin, such as, E. H. Carr, Joseph E. Davies, Grover Furr, Domenico Losurdo, Michael Parenti or Paul Robeson). The abnormal reactions of these negationist authors have been faithfully and usefully reproduced by Pierre Rigoulot and Ilios Yannakakis in their book, Un pavé dans l’Histoire. Le débat français dur Le livre noir du communisme (1998).

Unusually, Lionel Jospin, then Mitterrand’s socialist prime minister, with a well-known Trotskyist past, felt obliged to intervene personally in this debate in the National Assembly, thus flying to the aid of the communists, attacked by the right. On November 12, 1997, Jospin did not hesitate to proclaim “the” official version of history: “For me, communism is part of the Cartel of the Left, of the Popular Front, of the struggles of the Resistance… It has never infringed on freedoms… It is represented in my government and I am proud of it.”

Jospin was thus quick to bury the debate. The fault was to be found exclusively with Stalin, nor with Marxist socialism, nor with communism, and certainly not with French communists. It doesn’t matter what the reality is, what the objective facts are. The negationist reflex is always the same – to discredit the adversary; one can then blather on about intentions to make people dream.

Pierre Daix, a member of the Resistance, who was deported to Mauthausen, former editor-in-chief of Les lettres françaises and former deputy director of the Communist daily Ce soir, showed uncommon honesty and courage in his preface, written for the French-speaking public in 1963, to Solzhenitsyn’s book A Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovitch. “Let me say it right away,” he wrote, “there is no difference in nature for me between the camp of Ivan Denisovich and an average Nazi camp…” Horror is horror!

Taking the measure of the hostility evoked by Le livre noir, frozen and stunned by the virulence of the polemics, nearly half of the authors tried to distance themselves more or less from the main author of the work, Stéphane Courtois. One of them, Nicolas Werth, declared in Le Monde in 2000: “The more one compares communism and Nazism, the more the differences jump out.” Rather, let us paraphrase him: the more we compare them, the more obvious their analogies become.

But despite the socialist-Marxist fury and slander, the success of Le livre noir has not waned. It was enormous, having been translated into twenty-six languages and sold more than a million copies. The communists and their fellow travelers tried in vain to light counterfires, successively publishing two improvised works, the first of which was a botched job, Le livre noir du capitalisme (1998) and Le siècle des communismes (2000). The sales of both books were marginal, if not negligible, compared to those of Le livre noir. Finally, in 2002, a new collective work, entitled, Du Passé, faisons table rase! Histoire et mémoire du communisme en Europe (Let’s Wipe the Slate Clean: History and Memory of Communism in Europe), published under the direction of Stéphane Courtois, completed and extended the analyses of Le livre noir. In the preface to this book, Stéphane Courtois recalled the controversies that arose when Le livre noir was published and responded at length to its detractors.

Revolutionary Europe At The Beginning Of The 20th Century

The twentieth century is undoubtedly the time of the bloodiest international wars in modern history. An era of world wars, but also, for Europe, of the greatest internal or intrastate conflict; that of an overwhelming series of revolutions, riots, insurrections and civil wars. (See, Stanley Payne, Civil War in Europe (1905-1949), 2011). This succession of dramatic events began, between 1905 and 1911, with the Russian revolution of 1905, the Romanian peasant revolution of 1907, the Greek military coup of 1909 (a sort of counterpart to the Young Turks’ revolution of 1908), the Portuguese revolution of 1910, and the two Mexican and Chinese revolutions (from 1910 to 1911).

Many other insurrections or revolutionary civil wars occurred afterwards – in Russia in 1917 and in Finland in 1918; but also in many other countries, such as, Hungary (1919), Poland (1919-1921), Latvia (1917), Portugal (1919), Estonia (with a coup attempt led by the Comintern, in 1924), and Germany, where communist and revolutionary socialist riots and insurrections broke out from 1918 to 1923, and were severely repressed by Friedrich Ebert, a moderate social democrat, Chancellor and later President of the Weimar Republic. Again, Mexico (in 1922) and China (in 1927) must be mentioned, and of course Spain (with the socialist insurrection of 1934 and the military coup of 1936 followed by three years of civil war).

During World War II and immediately after the end of the conflict, three other countries experienced bloody civil wars: Yugoslavia (with the struggle between Tito’s Partisans and Mihailovic’s Chetniks, from 1941 to 1944), Italy (1943-1945) and Greece (1944-1949). Adopting a broader perspective, authors as diverse as Eric Hobsbawn, François Furet, Ernst Nolte and Enzo Traverso have come to use the concept of European civil war to refer to the entire 1914-1945 era.

Finally, during the Cold War (1945-1989), insurrections broke out in many Third World countries, including Vietnam, the Philippines, Malaysia, Cambodia, Cuba, Nicaragua, Angola, Mozambique, Biafra, Uganda, Rwanda, Somalia, Ethiopia, Sudan, Yemen, Chad, etc. Of all these “developing” countries, Castro’s revolution and dictatorship were among the least bloody, with approximately 10,000 victims for a population of 7 million (although this is only true if we exclude the number of deaths during military interventions in Africa and the number of exiles and refugees who disappeared at sea, which, according to the specialist Rudolph J. Rummel, could be over 77,000).

In Europe, the deadliest civil wars of the first half of the 20th century were in Finland and Greece, at least in proportion to the population. The Finnish socialists were the first socialists in Europe to launch a revolutionary insurrection against a democratically elected government, in 1918. The Spanish socialists were the second to do so, in 1934. In Finland, a country of 3.7 million people with a parliamentary and democratic regime, 36,000 people died in three and a half months of civil war (9,700 leftists were executed and 13,400 died in prison camps). In Greece, a country of 7.5 million inhabitants, in five years of civil war (1946-1949) 120,000 people died. In Spain, a country of 25 million inhabitants, in three years of civil war, there were approximately 300,000 deaths (150,000 died in combat or were murdered in the rear guard, in each of the two camps), to which must be added approximately 20,000 judicial and extrajudicial executions of left-wing militants between 1939 and 1942 (Socialist-Marxist historians put the number of executions carried out by Franco’s regime at 114,000 to 130,000, while their opponents estimate the figure at 25,000 to 33,000.

According to the most recent rigorous study by Miguel Platón, between 1939 and 1960, there were 24,949 death sentences, of which 12,851 were commuted and 12,100 were executed, a figure from which it is necessary to subtract the executions of common criminals and add the extrajudicial executions of the spring and summer of 1939, for a total of approximately 14,000. This frightening figure does not need to be exaggerated to reflect the scale of the repression that followed the victory of the national camp. Nevertheless, it remains light years away from the massacres committed by the National Socialist and Socialist-Marxist regimes).

The Soviet “Model” And Its Grim Record

Of all these revolutions and civil wars, the case of Russia remains the most emblematic. The bibliography on the events of 1917 is immense, but it is much more limited on the civil war. Two of the best works on the subject are those of Vladimir Brovkin, Behind the Front Lines of the Civil War: Political Parties and Social Movements in Russia (1918-1922), published in 1994, and Orlando Figes, A People’s Tragedy: The Russian Revolution: 1891-1924. We should also mention the book by the American Stanley Payne, Civil War in Europe (2010), and the works of four other historians: the socialist Marc Ferro (October 1917: A Social History of the Russian Revolution), the liberal, ex-communist Alain Besançon (Les Origines intellectuelles du léninisme, 1977), the conservative Richard Pipes (The Russian Revolution, 1905-1917), and the European nationalist, Dominique Venner (Les Blancs et les Rouges, Histoire de la guerre civile russe 1917-1921, 1997).

In 1917, the Russian autocracy was a dying regime even before it was attacked. The terrible mistakes of the Tsarina and Tsar Nicholas II, the sulphureous reputation of Rasputin, the dithering of the ministers, the incompetence of the various governments, the deterioration of the social and economic situation, the crisis of supplies and the terrible losses of the army (2,500,000 dead in two and a half years of war against Germany) were all skillfully exploited by the reformist and revolutionary opposition. On the eve of the revolution, everyone conspired against the regime – the revolutionary movements, of course, the Social Revolutionary Party (S.R.), advocating the populist and peasant uprising, and the Social Democratic Party, representing the Marxist tendency; but, also, the liberal monarchists, the republicans and the moderate socialists. As for the army, it was singularly divided.

The February Revolution of 1917 was a military uprising, grafted onto proletarian movements of limited importance, but skillfully exploited by the revolutionary minority. The day after the abdication of the Tsar, on March 15, 1917, the liberals and moderate socialists formed a provisional government, most of whose members were Freemasons. These men had no idea of the tide that was about to sweep them away. At their head, the revolutionary socialist, Alexander Kerensky, played a pitiful role. The majority of the army cadres welcomed the abdication of the Tsar, if not favorably, at least passively, as if it were a weight off their shoulders. Almost all the future leaders of the white armies, Kornilov, Alexeiev, Denikin, Kolchak, Kaledin, etc. were hostile to monarchic restoration. Totally discredited by the last years of the reign of Nicholas II, the monarchy had no really determined and unreserved defender.

The Bolsheviks (the majority and extremist faction of the social-democratic party), were able to set up an efficient and well-branched-out clandestine organization in the army and in the main industrial centers. In February 1917, they had only 24,000 members; but between April and October 1917, they recruited a considerable number of militants (300,000) and became masters of the country. However, this figure is only relatively significant when compared to the 170 million inhabitants. In fact, it is even proportionally smaller than that of the Spanish CP in July 1936 and that of many other communist parties in later periods.

On October 25, 1917, Lenin, Trotsky and their supporters launched a putsch or armed uprising in Petrograd against Kerensky’s provisional government, which they officially declared dissolved the next day. In the November 1917 elections, which had been planned before the October coup and which Lenin did not dare to suspend, the Bolsheviks obtained only 24% of the votes and were largely defeated. Lenin then decided to dissolve the democratically elected Assembly. On January 19, the Red Guards expelled the deputies manu militari and forbade them to enter the building.

The Bolshevik coup d’état and war-communism, whose foundations were laid by Lenin in the spring of 1918, were the two direct causes of the Russian civil war. The Treaty of Brest-Litovsk, signed in March 1918, between Germany and revolutionary Russia, was by far the most decisive “foreign intervention” insofar as it gave a second wind to the Bolshevik regime, enabling it to mobilize troops for the civil war. Unlike the Reds, the Whites had no political unity. They included all the opponents of Bolshevism, from the extreme monarchist right, which was in a very small minority, to the socialist-revolutionaries, as well as the republican conservatives, the Great Russian nationalists and the Cossack autonomists.

Unlike the Bolsheviks, the Whites had no worldview, no system of ideas, no powerful project, no mobilizing myth. They are very divided about the future of Russia. Two examples. First, the agrarian problem; while it conditioned the support of the peasantry (85% of the population), the Whites did not provide any solution. They should have supported the mass of small farmers to the detriment of the big landowners; but they do not do so. Second, the Whites should have supported nationalisms. But, blind, they sank into the reactionary defense of “Great Russia, one and indivisible.” Facing them, Trotsky and Stalin, undoubtedly the most important Bolshevik leaders, knew how to mobilize and put military specialists at the service of the revolution, and especially in much greater numbers than the counter-revolutionaries.

The human cost of the Bolshevik revolution in Russia is known today. Scientific estimates of the death toll caused by the dictatorship of the Communist Party since 1917, excluding the enormous losses of the Second World War, leave no room for doubt. The death toll from the first phase of collectivism alone, implemented by Lenin, assisted by Trotsky, from September to October 2018, is 10-15,000. In two months, the Cheka and the Bolsheviks executed three to four times as many people as the Spanish Inquisition did in three and a half centuries (2,500 to 5,000 deaths between 1478 and 1834), and two to three times as many as the Tsarist regime did in ninety-two years (four to six thousand deaths between 1825 and 1917). For the pre-Stalin period alone (1917-1921), the death toll is between 500,000 to 3,000,000.

The Communists and their fellow travelers maintain that there were at most one to three million deaths and only under Stalin. But according to the Soviet demographer Maksudov, the regime-change in Russia led to 27.5 million victims from 1918 to 1958.

In light of the archives of the former USSR, the Russian historian Volkogonov gives a total death toll of 35 million. Robert Conquest speaks of 40 million; Zbigniev Brzezinski of 50 million; Rudolph Rummel of 62 million. The demographer Kouganov and the president of the Commission for the Rehabilitation of Victims of Political Repression, Alexander Yakovlev, put forward an even more terrifying overall figure: 66 million dead. According to the most modest estimate, used by most Western historians, there were no less than 15 to 20 million deaths, a figure far exceeded by Mao’s China (40 to 68 million deaths according to Jean-Louis Margolin).

The World Balance-Sheet Of Socialism-Marxism

Stéphane Courtois summarizes the voluminous work that is Le livre noir in a particularly striking introductory chapter. He gives a first result which is nothing more than “a minimal approximation.” The death toll of communism is staggering: USSR 20 million, China 65 million, Vietnam 1 million, North Korea 2 million, Cambodia 2 million, Eastern Europe 1 million, Latin America 150,000, Africa 1.7 million, Afghanistan 1.5 million; the total approaches 100 million.

We knew almost everything about communism or Marxist socialism from the beginning, since the October Revolution of 1917, everything about the crimes, repression and horrors unleashed by the socialist-Marxist ideology. We knew that the criminal practices, that the “class genocide” was the consequence of the perversity of its ideology, of the morbidity of its leveling obsession. It was known that the Soviet concentration camps were an invention of Trotsky’s, and it was known that Stalin, and later Mao, had only taken up and continued the work where Lenin had left it. It was known that the essence of “real socialism,” of Marxist socialism, was cold terror, applied in a meticulous, almost scientific way. It was known, in short, that crime was at the heart of the theory and practice of “scientific socialism.”

But there still remains a need to be informed and to admit the horror. The most terrible criminal enterprise in history was aided and abetted to the end by a large part of the Western political and cultural elite. The responsibility and guilt of the latter are undeniable.

Unsurprisingly, the European people most immune to the socialist-Marxist ideology and system are those who have suffered from it for so many years, such as Hungary, Poland, the Baltic States, etc. But their leaders are, after all, no more critical than Russian President Vladimir Putin. During the Plenary Session of the 18th Annual Meeting of the Valdai Discussion Club (22.10.2021), Putin said unambiguously:

“The advocates of so-called ‘social progress’ believe they are introducing humanity to some kind of a new and better consciousness. Godspeed, hoist the flags as we say, go right ahead. The only thing that I want to say now is that their prescriptions are not new at all. It may come as a surprise to some people, but Russia has been there already. After the 1917 revolution, the Bolsheviks, relying on the dogmas of Marx and Engels, also said that they would change existing ways and customs and not just political and economic ones, but the very notion of human morality and the foundations of a healthy society. The destruction of age-old values, religion and relations between people, up to and including the total rejection of family (we had that, too), encouragement to inform on loved ones – all this was proclaimed progress and, by the way, was widely supported around the world back then and was quite fashionable, same as today. By the way, the Bolsheviks were absolutely intolerant of opinions other than theirs. This, I believe, should call to mind some of what we are witnessing now. Looking at what is happening in a number of Western countries, we are amazed to see the domestic practices, which we, fortunately, have left, I hope, in the distant past. The fight for equality and against discrimination has turned into aggressive dogmatism bordering on absurdity, when the works of the great authors of the past – such as Shakespeare – are no longer taught at schools or universities, because their ideas are believed to be backward. The classics are declared backward and ignorant of the importance of gender or race. In Hollywood memos are distributed about proper storytelling and how many characters of what colour or gender should be in a movie. This is even worse than the agitprop department of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union.”

We would like to hear sometime a Western leader express himself in this way on this subject.

Such cruelty, inhumanity and sectarian blindness – despite a century of irrefutable testimony and the atrocious record of historical research – is truly appalling. It is said that there are places of memory. But there are also privileged places of lies, manipulation and hate. “What serves the revolution is moral,” Lenin used to say. The historian, journalist and former trade union leader at the CFDT, Jacques Julliard, once declared: “To see the last Marxists in this country taking refuge in a morality of intention will remain, for those who like to laugh, one of the jokes of this end of the century.”

For my part, in the face of the denials of the communists, their social-marxist fellow travelers and other “useful idiots,” and in the face of their offenses against the memory of so many millions of victims, I am reminded of two funny lines from the film, Shawshank Redemption. Banker Andy Dufresne, sentenced to twenty years in prison for murder, meets his future friend Red for the first time in the yard of Shawshank prison. When Red asks him, “Why did you do it? Andy replies, “I didn’t do it, if you must know,” and Red jokingly replies, “You’ll like it here, everyone is innocent.”

Arnaud Imatz, a Basque-French political scientist and historian, holds a State Doctorate (DrE) in political science and is a correspondent-member of the Royal Academy of History (Spain), and a former international civil servant at OECD. He is a specialist in the Spanish Civil War, European populism, and the political struggles of the Right and the Left – all subjects on which he has written several books. He has also published numerous articles on the political thought of the founder and theoretician of the Falange, José Antonio Primo de Rivera, as well as the Liberal philosopher, José Ortega y Gasset, and the Catholic traditionalist, Juan Donoso Cortés. This article is translated from the French by N. Dass.

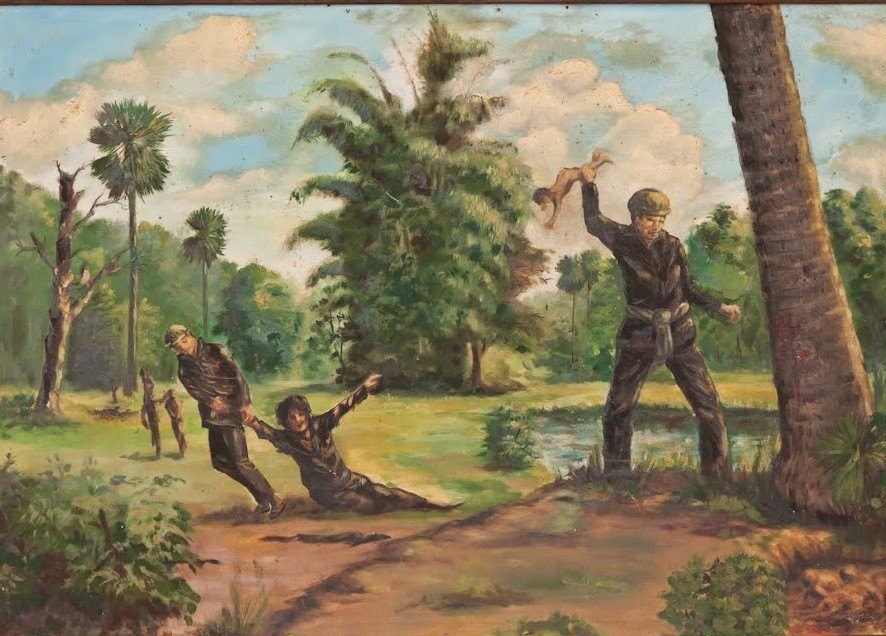

The featured image shows the Khmer Rouge killing babies at the infamous “killing tree.” A painting by Vann Nath, ca. 1990s.