This year marks the hundredth-year anniversary of the Russian Revolution, which began as moderate and democratic, but which the Bolsheviks violently hijacked.

In fact, the original Russian Revolution was simply a democratic replacement of Czarist rule.

The background to this transition was Russia’s disastrous participation in the First World War. Of all the belligerents in that conflict, Russia had the largest army (twelve million men), but also one which was the poorest equipped and rather badly led. Casualty rates were terribly high.

Often neglected is the fact that the war killed off the generation of men who by and large were loyal to the old Russia of the Czars.

The younger generation that replaced them were by and large radicalized and had no such loyalty. Socialism, of one form or another, held their true allegiance. The untold suffering produced by the war only justified their socialist ideals.

Thus, by 1917, disgruntlement in the army was high, and the Czar was seen as the cause of all the misery, both at home and on the battlefields.

And these troubles did not inflict the army alone. The general population too was a casualty of the war, for there were severe food shortages – malnutrition was a major cause of death among civilians throughout Russia. Thus, the war highlighted Russia’s economic flaws (poor land management, unstable food distribution, and low wages).

Then, there was the war itself. By 1917, nearly two-and-half million soldiers were dead, and about 5 million wounded. Death by starvation among civilians numbered nearly a million.

Thus, about two percent of the entire Russian population perished in just three years (at the start of the war, Russia had 175 million people). War-fatigue infected everything.

As with all such discontent, a seemingly innocuous event became the catalyst for cataclysmic change.

On February 18, 1917, workers at the Putilov steel mill, in St. Petersburg, went on strike. They demanded an increase in wages to meet the rate of inflation. The factory-owners refused to negotiate and locked them all out (some 20,000 employees).

In protest and solidarity, workers at other factories also struck, and within a few days most factories in the city were shut down.

Then, on International Women’s Day (February 24), the women also poured into the streets and joined the strikers.

Suddenly, over half-a-million angry people were no longer clamoring for a fair living wage; they were demanding a completely new social order.

Czar Nicholas II ordered that the unrest be put down, by force, if necessary.

This was a serious misreading of the mood of the Russian population, because Nicholas was unaware of one important fact – the goodwill of the people towards his rule was gone.

Instead of driving off the workers and the women, the soldiers sent to quell the disturbances refused to fire on their own people, and in most cases, joined the protesters.

Within a week, unrest had changed into a full-blown revolution.

Then, entire regiments mutinied, and the protesters now became a well-organized, and professionally armed, insurrection.

Government buildings were attacked, police stations ransacked, and arsenals looted for arms. The police could do nothing and often joined the rebels.

Nicholas then listened to more bad advice from his panicked generals, who suggested that since he was perceived to be the problem, the best thing was for him to abdicate, which he did on March 2, 1917.

All this in less than two weeks.

The parliament (Duma) was hastily reconvened, and the various political factions and parties (mostly democrats, moderates, republicans, conservatives, Kadets, or constitutional democrats, as well as some communists) cobbled together a makeshift government to take over from the Czar.

Needless to say, no one was ready for such a quick transition.

Because this was a haphazard coalition, it was deemed temporary, and therefore labeled, the Provisional Government. A more permanent regime would be elected by the people, once things settled down and an election could be properly organized and implemented.

The legitimacy of this temporary government was accepted by the officer corps of the army, the middle class, and the majority of the population. No one yet imagined that their revolution would be co-opted by the communists.

In fact, the Provisional Government had much good-will behind it. But, in true tragic fashion, this good-will was quickly squandered.

The fact was the Russians did not want to live under communism. The tyranny of socialism was imposed upon them because the governments they trusted (first the Czar and then the Provisionals) did nothing to counter communist strategies of takeover.

The communists had not just been sitting idly by. They had been busy building up a solid power-base – by 1917, the rank-and-file of the army, the navy, and the factory workers were staunch communists.

Then, the Provisional Government showed its lack of preparedness and began to make crucial mistakes.

The first of these was the decision to remain in the war and continue fighting the Germans, along with the other allies.

Germany had hoped that with the change in government, Russia would withdraw from the conflict. Despite the mounting losses, Russia still fielded the largest army, which meant Germany had been fighting on two fronts.

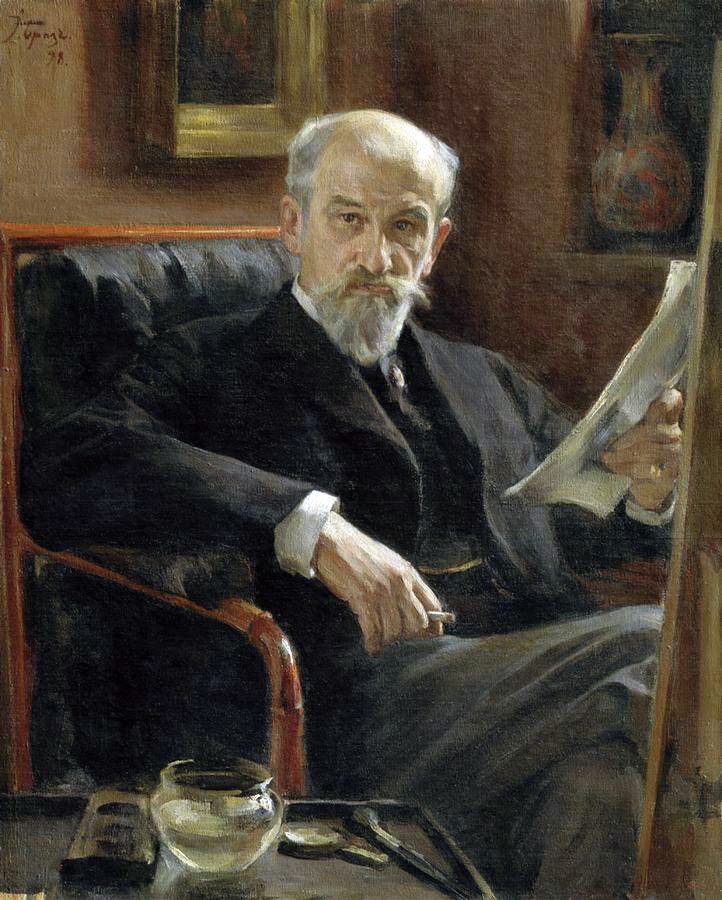

Now the Germans began to plot against the Provisionals. They contacted the chef leaders of the communists, both of whom were in exile abroad – Lenin in Switzerland and Trotsky in New York.

The communists had always opposed the war as an imperialist venture. The Germans set out to exploit this viewpoint by helping the communists grab power because they promised to withdraw Russia from the war.

It is at this time that the famous train-ride took place, where Germany secretly fetched Lenin from Switzerland, put him on a train to Finland, from where he got to Petrograd (the new name for St. Petersburg).

The Germans also likely funded Lenin and his Bolsheviks to further their aims. This is the notorious “German gold” charge against Lenin.

Before long, Trotsky also joined Lenin, but only after he was detained for four-weeks in Halifax, Nova Scotia.

The two men now began to plan a coup against the Provisional Government, and both understood that this could only be done by preparing their power-base for violent insurrection.

Was Lenin working for the Germans? There is much debate on the topic, but he was certainly furthering their aims, and he was certainly in Russia because of them. If they had not helped, he would have remained in Switzerland.

Within a few months, central councils, or soviets, were established in all the important cities. Their job was to foment unrest. This period of laying the groundwork for a Bolshevik Russia would become known as, “The July Days” in later Soviet lore.

Unlike the Provisionals, the communists were highly organized and therefore very effective in meeting their objectives. They had a power-base that was not only cohesive but extremely loyal.

The Provisionals, on the other hand, had no such cohesion, nor could they muster loyalty. They were really a hodgepodge group of factions, each with views that set them against each other. Even common consensus was a difficult thing, let alone concerted action.

None of them realized that they had one common enemy – the Bolshevists.

In fact, the very name, “provisional” seemed to sustain an ad hoc mentality, and thus there was always hesitation, and continual in-fighting.

The work of tending to the daily duties of good governance was neglected, which resulted in more mistakes, such as:

- The inability to become the permanent government of Russia.

- The loss of control over the army by not addressing the demands of the soldiers, the chief one being to drop out of the First World War.

- The inability to address the issue of land redistribution, which the peasants demanded.

- The inability to organize the proper distribution of food. People were starving.

If the Provisional Government had looked after just one of these dire problems, Russia’s future would have been democratic and republican, and far less murderous.

But nothing happened. The Provisionals decided that the war would go on, while the food problem remained unsolved, wages stayed low, and the land would not be redistributed any time soon.

Lenin, however, had the answers people demanded – he offered an alternative to the wretched status quo.

In a short space of time

- His Bolsheviks had full control of the army. His famous “Order Number 1,” which permitted ordinary soldiers to keep their arms, while also excusing them from obeying the orders of officers when they were off-duty – was very popular among enlisted men. It also successfully drove a wedge between the officers and the ordinary soldiers.

- He vowed to withdraw from the war immediately.

- And he offered a comprehensive strategy for land redistribution and food distribution.

People who hated the communists now began to give them a second look, since they alone seemed interested in addressing the grievances of the common people. Lenin decided now was the time for a coup.

Through effective agitprop (Trotsky’s expertise), armed riots broke out, the most serious of them occurring on July 16, 1917, when armed sailors, soldiers and factory workers surged into the streets and demanded a change of government.

The Provisionals appeared powerless to act.

But the appetite for violence was non-existent among the people, and the riots petered out by July 19. People saw this as a coup-attempt, and everyone turned on Lenin and his Bolsheviks – ordinary citizens did not want communism to rule over them.

The Provisionals bestirred themselves into action and arrested Trotsky and some other Bolshevik leaders, but Lenin slipped away and escaped to Finland, from where he continued the fight.

Again, when more decisiveness was needed, there was only vacillation, which led to more bad decisions – again, the war would be continued, nothing was done about the land problem, the people continued to starve.

By August, the ill-will for the Bolsheviks was vanishing. Had not Lenin alone promised the changes that everyone so badly wanted?

And there was always the in-fighting among the Provisionals. This time General Kornilov declared that he would seize power and bring much-needed stability to Russia. This message resonated with the people.

In a panic, the Provisionals called upon all parties, including the Bolsheviks, to help quell the threat (labeled a right-wing conspiracy). Of them all, only the Bolsheviks were well-funded and extremely well-organized.

Lenin understood that this was the time to quickly spread throughout Russia and take control. The Provisional Government had handed him the coup he wanted.

Kornilov might well have succeeded had he been a bit more patient and a little less confused as to what he should precisely do. Basically, he was not the man for the job. His outrage at the endless inaction could not be translated into a viable course of action.

Besides, the majority of the soldiers were already Bolshevik, or certainly sympathetic, and it did not take much convincing to get them to desert Kornilov.

The railway workers also lent a hand and sabotaged the various railway lines that Kornilov would need in order to make his threats a real danger.

Everything fell apart quickly thereafter, and in less than a week, he was arrested. Such was the “Kornilov Affair.”

But the general would dramatically escape, gather a division of crack troops, and begin a campaign against the Bolsheviks, promising to burn half the country if need be to get rid of them. By this time, the Bolsheviks were the only real fighting unit that the Provisionals had.

Kornilov proved an effective campaigner as he fought the various Bolshevik regiments that now spanned across Russia, consolidating power, enabled by the Provisional Government, whose “henchmen” they legally were.

Regions and even cities were left to resist and fend for themselves, as they tried to fight free of Bolshevik control. Civil war had now begun.

Korniliv emerged a natural leader of the resistance, but he was killed in April of 1918, when a Bolshevik shell landed on the farmhouse where he was staying.

The Bolsheviks were now the most powerful faction in the country. They were well-funded, well-organized, and very well armed. The army, the navy, the factories, and the railway lines belonged to them.

During this time, Trotsky formed the infamous Red Guard, composed of armed factory workers, who were fanatically dedicated to fighting for the communist cause. Later this unit would become the Red Army.

On October 22, Lenin returned from Finland, and rather famously declared that “Russia was the freest country in the world.” He would soon all that. In fact, Russia under Provisional rule was indeed remarkably free, a freedom it would not see for the next seventy-plus years.

The Bolsheviks were now ready to take full control.

In the early morning hours of November 7, they seized railway stations, telephone and telegraph offices, bridges, electricity plants, and the state bank.

The next day, the battleship Aurora opened fire on the Winter Palace, where the Provisional Government was headquartered.

When the Red Guard stormed the Winter Palace, they found no one inside. The Provisional Government had fled, down to the last man. Tragically, they abandoned Russia to Lenin.

The only people of real importance, still left in Petrograd, were the ex-Czar’s family. There was no one from among the leaders.

In one of those misfortunes of histories, the royal children had come down with measles, and their mother thought they should not be moved.

Little did the Czarina realize that by not acting, she had sealed her own fate and the fate of all her children. It would have been far better to flee with sick children, because the deaths that awaited them all at the hands of the Bolsheviks would be nightmarish.

When the Red Guard arrived to arrest the royal family, there was no one around to protect them, except for a few guards who put up no resistance.

On the evening of November 8, Lenin gave a banal, but dire, speech, in which he declared that he would now “proceed to construct the socialist order.”

But this new order would first need a long bloody Civil War, the murderous Red Terror, Lenin’s infamous Hanging Order, the killing of rivals by Stalin, the great purges, the annihilation of men and women of undesirable classes – all those cruel components of a methodical class war that alone can establish the dictatorship of the proletariat.

And yet Lenin’s rule would also be short-lived. The maelstrom of blood that he unleashed would burgeon beyond his control. He would be shot, survive, and then eventually die in 1924, likely “on the operating table,” a euphemism used at the time to describe political assassination.

His executioner would be one of his low-grade henchman by the name of Stalin. Many more millions would then die to continue building the “socialist order.” Stalin was fond of saying that he had great plans for Russia, but people kept getting in the way.

The terror Lenin unleashed would take many decades to wind down, and then finally disappear. The period from 1917 to Gorbachev’s perestroika of 1989 should really be seen as one long Dark Age for Russia.

It is only now that this nation is emerging into the hope and future that everyone imagined and hoped for, when the Czar abdicated and Russia became “the freest country in the world.”

Only now is this great land awaking to its promised Renaissance, which it has dearly purchased, with the blood of millions of its people.