When we think of the Soviet Union, we mostly think of it as a fully realized totalitarian state. We think of Stalin, of World War II and of the Cold War. Lenin is a shadowy figure to most of us, usually lumped in with the chaos that preceded and surrounded the Russian Revolution.

As a result, biographies of Stalin and histories of the Cold War are a dime a dozen, but there are few objective biographies of Lenin. Lenin, though, was the true author of Soviet totalitarianism, and, more importantly, he, and he alone, was the indispensable man to the creation of Communism as a realized state, even if he did not live to see it.

dozen, but there are few objective biographies of Lenin. Lenin, though, was the true author of Soviet totalitarianism, and, more importantly, he, and he alone, was the indispensable man to the creation of Communism as a realized state, even if he did not live to see it.

His life, therefore, is important, in that it illuminates history, and also in that it provides, in some ways, an instruction book for those seeking change today.

You would think I, at least, would know more about Lenin that I do. My father was a professor of Russian history, my mother’s family fled Communist domination in 1945, and I grew up through the ending stages of the Cold War.

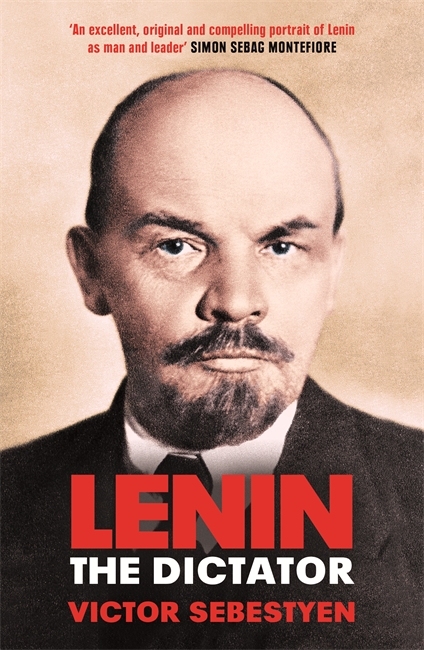

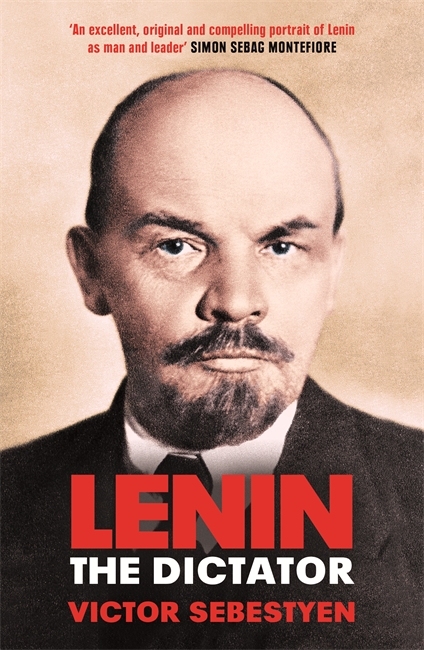

But really, until I read this book, by Victor Sebestyen, I knew very little, other than that Lenin was the fulcrum around which Communism turned from a mere extremist ideology of babblers and dreamers to an iron hand that nearly crushed the world. (And also that his body was, oddly, still embalmed and on display twenty-five years after Communism itself died.)

Sebestyen’s book does an excellent job of covering Lenin’s life, in highly readable prose and without getting too bogged down in details. This book also has the advantage of being written after many archives were opened following the fall of Communism.

Although those archives didn’t change the major outlines of Lenin’s life and career, Sebestyen adds quite a bit of personal flavor about Lenin that was missing until those archives became available, especially regarding his irregular relationship with his quasi-mistress, Inessa Armand.

I find myself finding Lenin strangely attractive, in these latter days, when everything old is new again. Not his goals, which are silly and pernicious, or his fanatical devotion to an ideology, which, no matter the ideology, is always a mistake.

But his discipline and his methods of acquiring power show a purity and consistency of purpose which is totally lacking among conservatives today, who instead spend their days on the disorganized defensive, and he always demonstrated a grasp of reality which is totally lacking among progressives today. (Lenin also loathed modern art, and always dressed nattily, both to his credit).

I don’t think I’ll be putting up a portrait of Lenin anytime soon, or ever, but after reading this book, I am beginning to think his personality and methods will reward close study (although, as with Milton’s Satan, one must be on his guard not to be seduced).

Pre-Revolutionary Russia seems very far away from us. Poor, corrupt, and intensely authoritarian, wracked by violence on a scale incomprehensible to us (tens of thousands of government officials were assassinated in the last few years of the Romanovs’ rule, and then there was the whole World War I thing), it is difficult at first to see many parallels to our time.

Still, there are more than a few, and even where there are no parallels, there may still be lessons. Sebestyen agrees, citing the loss, then as now, of “confidence in much of the West in the democratic process itself,” “Lenin would very probably have regarded the world of 2017 as being on the cusp of a revolutionary moment. . . .

The phrases ‘global elite’, and ‘the 1 per cent’ are now used in a decidedly Leninist way. It is unlikely that Lenin’s solutions will be adopted anywhere again. But his questions are constantly being asked today, and may be answered by equally bloody methods.”

Lenin (that is, Vladimir Ulyanov, his real name) was born in 1870 and died in 1924, at only 53. He was born in Simbirsk, a sleepy provincial town, to bourgeois parents—his father was a successful civil servant in the education ministry, a moderate liberal whose attempts at education reform were largely frustrated by the 1881 accession of Alexander III (whose more lenient predecessor was assassinated).

Lenin’s father died in in 1886, when Lenin was only 16, and the following year, his brilliant and idolized older brother, Sasha, was hanged for his role in an assassination plot against the new Tsar. This, along with the social isolation that descended as a result on the family, gave Lenin a lifelong hatred of the Tsars and the bourgeois, before he became a Marxist ideologue.

I suppose this is yet another example of how personal events often shape great men, from Alexander Hamilton’s illegitimate birth on Nevis to Donald Trump’s poverty-wracked upbringing in Appalachia.

Lenin’s education was somewhat irregular, since he was denied the usual university placements due to his brother’s politics, and due to his own, which quickly became radical, although he was not a leader of any groups at this time.

Still, he managed to become highly educated, while being formed by books like Nikolai Chernyshevsky’s What Is to Be Done?, a strident work of fiction about an iron-willed revolutionary, which Sebestyen says is nearly unreadable today but which greatly affected Lenin, who consciously modelled himself on the book’s hero.

Not that he completely ignored pleasures—his greatest was nature, especially walks in nature. (It is strange in these days of constant connectivity to read how Lenin, even at busy and critical times in his life, would take multi-week vacations in the country, doing nothing and being functionally unreachable by other Bolsheviks).

Naturally, he practiced as a lawyer for some time (successfully getting the necessary certificate of loyalty and good character from the Okhrana, the cruel but buffoonish Tsarist secret police, in 1891), but quickly became a full-time Communist agitator, a job he kept for the rest of his life.

Unlike most cult leaders, Lenin lacked interest in vices of the flesh. He was not corruptible by money, women, or, really, power. He didn’t smoke or party. His forte was discipline and focus. No doubt connected to this, from the beginning Lenin betrayed zero human sympathy beyond his immediate family circle.

In 1892 he opposed famine relief in the Volga, because the famine was desirable to show that capitalism was incompetent and dying—never mind that thousands of peasants were dying too. This well illustrates ones of Lenin’s guiding principles, that “Our morality is new, our humanity is absolute, for it rests on the ideal of destroying all oppression and coercion.”

As Ryszard Legutko has pointed out, there is a very significant overlap of theory and practice among so called “liberal democracy” and Communism, and one reason Communists were never punished is that the “liberal democrats” currently in control of most of the West had much more sympathy for Communism than for traditional currents of thought.

More broadly, across the West today, any action, however damaging to real human beings, is justified by the Left by a call to “emancipation,” identical to Lenin’s, with the same disregard for actual people. Certainly, the Left would love to take advantage of a famine or any human disaster even now, if it could be tied to increased emancipation.

Their disinterest in the epidemics of opioid addiction, dependency, and despair afflicting the deplorable, Trump-voting white lower classes is evidence enough of that. If they could cause a famine among those people, they would, and laugh.

Much of the book is taken up with narration of Lenin’s combat with other elements of the Left, tied to a never-ending whirl of conspiratorial international meetings, avoidance of arrest by various police forces, struggles for control of newspapers, and hard work to smuggle into Russia and distribute those newspapers.

Those newspapers had a great effect within Russia and gave the Bolsheviks much of the power they accumulated. Such media not only sways opinion, but can create opinion from whole cloth, and also provide readers with a sense of comradeship and non-isolation, which is why today’s Left so aggressively and increasingly censors conservatives online.

Naturally, Lenin was eventually arrested, and as was usual under the Tsars, merely sentenced to a few years of internal exile, which he used to study hard.

As Sebestyen notes, “The Tsarist penal regime was far more benign for political prisoners than it would be in later years under the Soviets, where torture and summary execution were the norm.” (Not that it was all fun and games—plenty of people died as a result under the Tsars, especially those exiled to less salubrious places than Lenin was).

Eventually Lenin left Russia, moving to Germany, then England, then Switzerland, all the while continuing revolutionary activities. He worked incessantly, primarily on writing, both journalism and books.

As always, he stayed focused. Most of all, he consistently offered a simple message of “optimism and hope. He told his followers that they could change the world in the here and now, if they followed a set of essentially easy-to-comprehend steps and believed in a few fairly straightforward propositions.”

Along the way Lenin collected various followers and allies (most of whom he later broke with), from Leon Trotsky to Grigory Zinoviev. Sebestyen covers all this with verve, adding bits and pieces of interesting information. For example, I did not know that that suffragette Sylvia Pankhurst, lionized today, was a Communist, and a vicious one at that.

And, then, came Lenin’s moment, created by World War I and the incompetence of Nicholas II (whom Sebestyen regards with very strong distaste for his ineptitude).

The economic collapse and dissatisfaction of the masses of peasant soldiers created the conditions without which the Bolsheviks would never have had the chance to grasp power (not that the soldiers had any interest whatsoever in Bolshevism—what they wanted was “anarchistic freedom,” and Lenin had that on offer, or so it appeared).

But they, in the person of Lenin, did have that chance, and they grasped it. Not to overthrow the Tsar, as many ill-informed people think, but to overthrow the democratic successor government, in a coup vividly covered by Sebestyen, which succeeded even though its imminence was the worst-kept secret in Russia and it was incompetently executed.

It is a commonplace that the Kerensky government was run by fools, and that is very evident in the account given here. They responded, when the British offered to stop Lenin from returning on the “sealed train” provided by the Germans, that since Russia’s new government “rested on a democratic foundation . . . . Lenin’s group should be allowed to enter.”

And rather than seizing Lenin when he arrived, killing him and throwing his body into a canal, as had been done with Rasputin and should have been done with him, they dithered. They did not know their enemy. This is not surprising, though.

As history repeatedly shows, the vast majority of those who are threatened by bad people in any way, rather than meeting the threat with action, prefer to retreat into half-, or quarter-, measures, or into fantastical hopes that somehow they will be rescued by an external agency.

As Benjamin Franklin, and not the Bible, said, “The Lord helps those who help themselves.” But helping themselves is something people usually find hard to do.

My main interests in Lenin are two, although they are closely related. My first interest is that Lenin shows us how the Left always thinks and operates, then and now, since Lenin first established the template for successful Left dominance.

Therefore, studying Lenin has tactical value in the wars to come. We can closely examine how and why this is so through a particular ideological obsession of the modern Left, which this week has yet again raised its ugly head—gun control. (It is also an obsession of the past Left—one of the Bolsheviks’ first edicts was to confiscate all privately held guns, under penalty of summary execution for failure to comply, something that the odious Shannon Watts and Michael Bloomberg would, if they were being honest, doubtless completely endorse).

For the Left, gun control is justified not by its demonstrated, or even possible, benefits to society (though laughable claims along those lines are mouthed for propaganda purposes). Rather, it is justified by its purposes, which are to ensure that the ruled know that they are ruled, to ensure they continue to be ruled, and to signal to the rulers, the Left classes, their supposed moral superiority.

Gun control is not a policy choice; it is the opium of narcissistic tyrants.

So, to take one example of Left tactics, Lenin continuously used violent language which, in his own words, was “calculated to evoke hatred, aversion, contempt . . . not to convince, not to correct the mistakes of the opponent, but to destroy him, to wipe him and his organization off the face of the earth.”

Or, as Sebestyen characterizes it, “Communist Parties everywhere, even following the collapse of the Soviet Union in the early 1990s, learned that it made sense to play the man, not the ball—and how to do it with ruthless efficiency.”

But Sebestyen is wrong—it’s not Communist Parties, it’s also the entire progressive Left, and has been since Lenin (whose broad program they have always supported). These tactics of “hatred, aversion, contempt” continue to be on full gruesome display at this very moment in the disgusting, hate-filled propaganda campaign being waged by the Left (who totally control the news-setting media, and thus the narrative, by deciding what constitutes “news”), to demand mass gun confiscation, in response to school shootings that occur largely because of their social policies.

The good news, I suppose, is that Lenin was using a new tactic, successful largely because nobody knew how to respond to such tactics—either his Left opponents, whom he steamrolled, or his Right opponents. We do know how, and that’s to hit back twice as hard.

We just have trouble executing the right tactics, because the Republicans are run by weak men who are happy to bow and scrape to their betters as long as they are thrown a few crumbs and invited occasionally to the right parties.

To take a second example, during a 1922 famine, “Lenin deliberately used the famine as an excuse to launch an assault on the clergy [to seize liturgical vessels and other metals]. . . . ‘We must seize the valuables now speedily; we will be unable to do so later because no other moment except that of desperate hunger will give us support among the masses.’ ”

This use of unrelated, manufactured or fictional crises as the moment of action, whether because the masses are desperately occupied with their own concerns (as Rahm Emanuel famously openly admitted under Obama) or in order to propagandize the masses by manipulating irrational and immature emotions (as with gun control) is also a universal tactic of the Left, also largely invented by Lenin.

Its modern counter is less obvious than the counter to violence in language and action, and probably requires structuring and maintaining permanent and binding organizational brakes on rapid legislative or executive action, the opposite of the “more democracy” constantly called for by the Left.

And to take a third, closely related but distinct, example, the Left does love themselves a good Reichstag fire.

The Bolsheviks used a 1918 assassination attempt on Lenin by a (non-Bolshevik) leftist as an excuse to eliminate opponents and generally consolidate their power through a wave of mass terror.

With gun control, the exact same tactic is used—not by killing opponents, or not yet, but by suspending all normal processes of republican debate and decision-making, demanding that “something must be done”—naturally, something that aligns perfectly with their pre-existing ideological goals and plans, no possible deviation from which can be discussed, much less implemented, and which must be implemented immediately, though no reason for the urgency is given, or can be given, other than the need to impose their desires on the rest of the nation.

The classic example of this is the repeated use in state legislatures of “emergency” procedures to pass gun control measures after a shooting, formally eliminating any debate or public input, and demands for similar action at the federal level.

So far, so generic, really. The modern Left is unscrupulous and often evil, no doubt, but this is not news, and I am being repetitive, if you look at other writings of mine. More interesting, I think, is my second interest in Lenin—as a model for how a reactionary movement might acquire power in America.

By definition, nearly, a reactionary movement contemplates a formal concentration and reallocation of power, rather than a formal diffusion, as some conservatives would have it.

That is, if the Enlightenment project of ever greater autonomy and atomization is defective, and as part of that project the Left has consistently advanced their goal of concentrating power to themselves while pretending to increase democracy (that is, allowing democracy as long as it reaches the correct conclusions), breaking both the Left concentration of power and the forms of sprawling, ever-expanding democracy is necessary to remake the political system.

Presumably this would involve some form of restricted franchise and a return to a mixed form of government (e.g., returning to the Senate being elected by state legislatures), but the details do not matter here. We can simply call it the “Program,” for now. The question is, how is the Program to be accomplished? And here Lenin is instructive.

I don’t mean Lenin in the substance of his ideas, essentially 100% of which were pernicious, and the vast majority of which were outright evil. Nor do I mean Lenin in the substance of his implementation, which, flowing from his ideas, necessarily implied and required terror and mass murder.

Rather, I mean Lenin in his efforts to gain power so that he could implement his program, which is just about 180 degrees from the Program.

So, how is Lenin instructive? Here, a few thoughts. Lenin thought long term, but with an eye to the main chance, which he took when he got it, unlike most men in his position, who would have dithered. “There are decades when nothing happens—and there are weeks when decades happen.” “Timing is all.”

But without his discipline and focus, he would have had no chance at all, willingness to risk everything or not. And, while an ideologue, he was willing to be flexible in his interpretation of theory, rather than getting bogged down in debating ideological purity (as Communist splinter groups, as well as conservatives, have always been prone to do, while the successful Bolsheviks, like today’s Left, paper over differences to achieve power).

All these practices allowed Lenin to seize opportunities created by chance the mistakes of his enemies. “We made the Bolsheviks masters of the situation,” said Sukhanov, an opponent of Lenin [on the Left]. “By leaving the [1917] Congress [of Soviets] we gave them a monopoly on the Soviets. Our own irrational decisions ensured Lenin’s victory.”

Yes, but only Lenin’s ability to take advantage made the Mensheviks’ mistakes matter.

These are all mental tactics. Practical tactics are just as important, and often just as difficult to execute. I mentioned newspapers, the media, above—not its control, which Lenin grasped as soon as he took power, but the earlier dissemination of ideas through media, both for their own contagion, and to buck up your allies.

Behind newspapers, behind organization, behind everything, though, is funding—obtaining, and keeping on obtaining, cold, hard, cash. Far more than other Left groups, the Bolsheviks were able to scoop up enormous amounts of money from a huge range of sources—not just the bank robberies famously conducted by Stalin, but from a mélange of non-radical liberals hoping to show their bona fides, cynical business magnates covering all the bases (they thought), and the German government.

According to Niall Ferguson, the Germans alone supplied Lenin with the modern equivalent of $800 million, in gold currency. The Program requires cash, not some mutterings on little-trafficked websites like this one, and principle only takes you so far. And, of course, the Program requires people, who are organized, both by the desire for common participation in a goal, and by that cash. Lenin excelled at all these practical tactics, and he was indefatigable.

How exactly to fit these tactics into the implementation of the Program I am working on, and will discuss in detail on another day. But certainly the tactics of today’s American conservatives bear no relation to Leninist tactics, which is to say, they bear no relation to the tactics necessary to break the autocracy of the Left. (This is doubtless why Steve Bannon referred to himself as a Leninist, or so it is said, which the ignorant took to mean that he was referring to himself as a Communist).

Continuing what we are doing will not result in anything but the continued domination of the Left over American life and culture, and the necessary degradation and diminution of America, and the West in general. Thus, I will offer a full solution, and it will not be ideological. But you will have to wait a while.

What I will not do is write persuasive arguments about policy. Not so long ago I regularly engaged the Left in discussion, primarily through Facebook (since the New York Times has not come knocking on my door). As far as gun control arguments go, I always decisively won every argument.

This is not because I am so awesome, but because gun control proponents, with zero exceptions, have no idea what they are talking about, and rely exclusively on shrill emotion, backed up by lies. I am off Facebook, for the most part, and totally off for Lent and Eastertide.

But today, in order to push back slightly against the organized flood of violent hatred directed at gun owners, I changed my profile picture to the NRA symbol. Two Left friends of mine immediately commented. What they said, I don’t know, except that one mumbled something about “blood money” (today’s meme, organized and distributed centrally to the drones like my friend).

I don’t know what they said because I deleted both comments without reading them. What profit to talk, since they are not interested in reasoning, but in moral preening and tyranny?

On many issues, such as guns, and perhaps on the most central social issue of all, how we shall be governed, the time for talking is over, on Facebook and elsewhere, with friends or with enemies. The time for action is here. The only question is how much chaos will result before the world is remade.

Charles is a business owner and operator, in manufacturing, and a recovering big firm M&A lawyer. He runs the blog, The Worthy House.

The photo shows, “In the Basement of the Cheka,” by Ivan Vladimirov, painted in 1919.