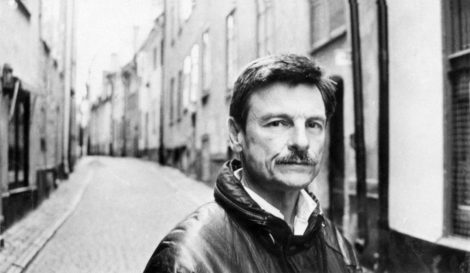

Andrei Tarkovsky made seven full-length films, as well as a few short ones. His work full participates in the grand tradition of Russian film established by people such as Sergei Eisenstein and Vsevolod Pudovkin.

As such, Tarkovsky’s films have a character that is uniquely visionary, while imbued with history, especially evident in his epic “Andrei Rublev” which portrays the life of the famous monk and icon painter, who strives to create beauty in the harsh brutality of the Mongol invasion of Russia. Given his ability to use history, it is not surprising that Russian authorities saw his films as works of dissent. This led to great hostility to his work and inevitable censorship; and worst of all, neglect. He died in exile in Paris 1986.

beauty in the harsh brutality of the Mongol invasion of Russia. Given his ability to use history, it is not surprising that Russian authorities saw his films as works of dissent. This led to great hostility to his work and inevitable censorship; and worst of all, neglect. He died in exile in Paris 1986.

Tarkovsky’s films also show a marked use of dream sequences that resonate with deep meaning, and serve as symbolic reference points for the entire film itself.

In one sense the dreams that these films present serve to subvert the entire construction of reality that is being portrayed; and this subversion is made evident by the juxtaposition of the dreams as the ideal, while the mundane is represented as brutal, cruel, and senseless.

As well, there is the important distinction to be made in the conflict that this juxtaposition raises, namely, the very Russianness of the dreams and the prevalence of western ideas in the mundane reality within which these dreams occur.

It is important to bear in mind that Russian culture is replete with this western/eastern conflict, wherein the identity of Russia itself is marked.

The question again and again asked is this – is Russia fundamentally eastern or western. Tarkovsky’s dream sequences in his films address this fundamental question. Thus, dreams in Tarkovsky’s film fulfill two notions: they are a representation of the ideal, and they address the issue of Russia’s identity.

The immediate impression that one receives while watching a Tarkovsky film is the manner in which the quintessential image of Russia is blended with a ready acceptance of everything that is western.

We are presented with actions, faces, words, suffering, and deprivation. This is the mundane aspect of any Tarkovsky film. Against this immediate backdrop is the dream, which in fact is really a memory, a recurrent nostalgia for a way of life that has long vanished, or perhaps never existed.

This is what makes these dream sequences ideal – in that they are mythic, and they partake in mythic structures, in that they present an often “heroic” hyper-reality, which functions as a commentary of the actual reality of the characters in the film.

This is especially evident in Tarkovsky’s early films, such as “Ivan’s Childhood,” and “Mirror,” where he explores the sustaining power of both nature and the Russian tradition.

It is also interesting to note that in these two early films this ideal setting is dominated by the figure of the mother. These films are idyllic pastorales that also expound the ideology of “Mother Russia:” the vast stretches of forests, simple peasants, and domed churches. Thus, dreams are an attempt to capture the lost moment, the perfect harmony that once existed, but is now vanished, and can only be captured in dreams.

This need to dream becomes essential to the verity of the film because there is only bleakness otherwise; and this bleakness is the result of love, either for another person or the land, that is, Mother Russia; and this love is a continual heartbreak.

There is an absurdity to this love, because this love can absorb pain and can also share out joy. In “Ivan’s Childhood” and “Mirror” we see this love being demonstrated in the mother figure that animates both these films with love, sacrifice, as well as vulnerability. Thus, dreams are feminine, just as Russia is seen as the “motherland” rather than the “fatherland.”

The same process is evident in “Solaris” where we meet Kris Kelvin’s mother, who properly has little relevance to the plot of the film, but represents the capacity to dream. It is important, therefore, to bear in mind that dreams are also catalytic – they allow for existence despite the harshness and the unyielding bleakness.

In effect, for Tarkovsky, dreams are akin to memories and reminiscences, and all three crowd his films, and serve as forces of coherence and order. Thus, dreams are also an attempt to bring order to chaos. It is chaos that pervades the characters lives in Tarkovsky’s films. When they dream they seek to fashion this chaos into a semblance of order; and that order is minutely married to the ideal and idyllic Mother Russia.

Dreams, then, become a commentary on the familiar by way of memory, which in turn is an idealized projection. Thus, there is a sense of otherness to the dreams in Tarkovsky’s films. This otherness inhabits the subconscious, which is often ignored, given the demands of daily reality.

However, Tarkovsky uses dreams to bring about self-realization and the possibility of authenticity. Dreams, in effect, bring wholeness and completeness, because they link the fragmented self with the wholeness of the past – and this past can only be ideal because it is complete.

Thus, the characters dream in order to become whole. Similarly, they also remember and hallucinate, which are no more than extended paradigms for the perfected, ideal dream world.

This contrast between reality and the dream leads to a film that does not have a linear plot, nor does a Tarkovsky film fulfill stereotypical expectations. Rather, his films are elliptical and often “intellectual” and are therefore often deemed as obscure.

This is best described by his method of making films in different languages, such as “Nostalgia,” which is partly in Italian, and “Sacrifice,” which is partly in Swedish. This use of different languages also mirrors the nature of dreams – because the mixing of languages follows a process similar to dreams.

Thus, Russian is placed within the context of Italian or Swedish, which is certainly a jarring experience. Similarly, a dream is placed with the context of mundane reality, with equally jarring consequences. What we perceive as normal is in fact informed by the unexpected and the unusual.

People speak Swedish or Italian in a Russian film because they trail a different set of values, cultures, and a different history. And on an individual level, dreams allow us to access different values and cultures, and even history.

Thus, the dissonance is not with the juxtaposition, but it is with the context – what we expect is not what we often get. And this is the jarring fact of modern life.

In effect, dreams become a commentary on modernity itself. Society, which should provide us with solace and comfort, in fact isolates us and therefore fragments us, so that we become little more than individuals who can only respond to what lies outside of us, rather than becoming controllers of our own lives.

It is this process of action and reaction, which is so much a definition of modern life, that Tarkovsky’s dream sequences seek to address and understand.

Given this penchant for using dreams in this way, it is easy to charge Tarkovsky with being too allegorical and perhaps too obscurely moody.

For example, we have the horses appearing at the beginning and the end of “Andrei Rublev; there is the ticker-tape sequence in the last cathedral scene in “Nostalgia;” or the scattering of paper at the end of “Ivan’s Childhood.”

These sequences are exactly what dreams are all about, or why Swedish and Italian are spoken in a Russian film. They are part of the dream world that Tarkovsky wants to create; and this dream world is often irrational, inexplicable, strange, obscure, and at puzzling. But we need to realize that dreams also contain depth of meaning, which can only be recovered by a process of realization.

As well, n “Sacrifice,” Tarkovsky’s last film, Alexander’s lengthy speeches can be construed as verbal dreams, especially since these speeches are placed within the context of scenes such as the fire and the lonely road.

Thus, dreams may complicate reality, but they also lead us away from the process of conditioned responses; and perhaps this is why dreams are difficult to understand, just as Tarkovsky is often difficult to understand.

However, this difficulty is also a very important aspect of dreams for Tarkovsky – for by making things difficult, Tarkovsky emphasizes the process of alienation that we feel in the modern world. Often, we are placed in contexts that we know nothing about. Often we are baffled by life, and what it all means.

Tarkovsky’s films mirror this alienation. His allegories and his wordiness show our own psyches at work – how we handle a complicated reality within which we must live our lives. Dreams attempt to make sense of the vast chaos that stretches before; they serve to integrate ourselves within ourselves.

Of course, they cannot integrate us within society – that is not Tarkovsky’s concern – because to do so would in effect create another dream. When a solution is offered as to how life should be lives, or how happiness, fulfilment can be achieved, we veer into propaganda, where struggle always leads to happiness and fulfilment.

But life is often harsher than that, and Tarkovsky wants to make sense of this harshness, and thereby soften it by cushioning it with memories, dreams and even hallucinations.

As well, dreams provide a metaphysical experience in that we move into an inner world of the characters, within the context of the outer world of history and politics and personal struggles.

This inner world is the realm of dreams, where narrative is subverted and lost time is remembered. This inner world also functions to highlight the perfectibility of the individual. However, whether this perfectibility is available to human beings is a question that cannot be addressed in Tarkovsky’s films because wide gap that lies between the world of dreams and the world of reality.

It is this gap that is the source of tension and lack that permeates and affects the characters in a film such as “Sacrifice,” especially Alexander, whose discourses can only be verbal dreams at best.

And his discourse stands in direct opposition to the flow of reality outside, such as the road, which leads forever onwards, but we cannot know to what ultimate destination. In the same way, the horses that bookend “Andrei Rublev” are allegories of the disruptive force of dreams, which barge into the passive flow of mundane reality with all of their escapism, their visions of perfectibility, and their allure of a pastoral, peaceful, and harmonious past.

As discourse, dreams become the lens through which society and the individual are read. They are not so much as wishful thinking, or repressed desire; rather they are a very real force, which can shed light on the disparity of life, and the process of alienation that is part of the modern experience.

It is for this very reason that dreams function as allegories. For example, “Ivan’s Childhood” is layered with many war stories. These stories do not function to give meaning to the larger plot; however, they do serve as allegories of perfectibility.

Through their lens we confront values such as loyalty, memory, and courage. These stories also serve to create a dream world, which is a combination of hallucination and reality, which is rather typical of Tarkovsky’s method.

This combination is reflected in the narrative as well, in that the mother often intervenes, as the war stories are being told. As well, we have the juxtaposition of Ivan’s child-like innocence and his ability to kill as a guerilla fighter.

Even here we see the particular combination of the ideal and the real – the child-like Ivan is also a seasoned killer. Perhaps this is why Ivan dreams of a hand in the beginning of the film, for a hand can both build and destroy.

In this way, Ivan as a character frequently crosses the boundaries between dream and reality, and thereby he justifies his own life, which is a complex unity of innocence and bloodshed.

Once when we are given perfectibility in dreams, we are therefore also shown a dis-junction between the inner and the outer worlds.

This is well portrayed in “Andrei Rublev,” here the religious fervor of the icon painter Rublev is juxtaposed with a harsh, medieval world that cares little for beauty and art.

The traditional icons underscore the process of perfectibility, where despite the disjunction that one experiences in the world outside, the inner world becomes a complex realm where wholeness and harmony can be achieved and the emptiness of the modern world thwarted.