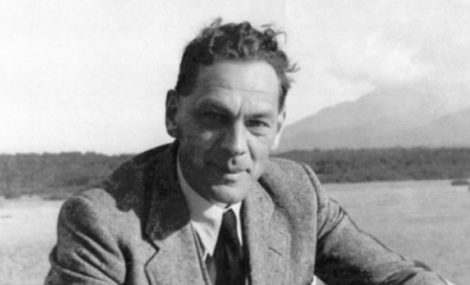

The Soviet intelligence officer Richard Sorge was worth an entire army. His reports not only saved Moscow during WWII, but also significantly contributed to the victory over Nazism. However, Stalin had a peculiar way of “thanking” him, allowing him to be hanged by the Japanese.

In autumn 1941 the outcome of the whole Soviet-German war was at stake: Hitler’s troops were at the gates of the Soviet capital. However, after some brutal, exhausting clashes, the Soviet army went on the counteroffensive and drove the enemy back.

Victory became possible due to the arrival of fresh Soviet divisions, redeployed to Moscow from Siberia, where they had been awaiting a Japanese attack.

Stalin would never have allowed a weakening of the Soviet forces in the Far East if Soviet reconnaissance officer Richard Sorge had not reported that Japan was not preparing to attack the Soviet Union in 1941. Thus, one man saved the capital of the Soviet Union when all seemed lost.

Richard Sorge was born to become an intelligence officer. Smart, attractive and elegant, he was good at making useful acquaintances, which he exploited perfectly in getting vital information.

At the age of 29, young German communist Richard Sorge moved to the Soviet Union, where he soon was recruited by the Soviet intelligence service.

Union, where he soon was recruited by the Soviet intelligence service.

In 1933, Sorge was sent to Japan, where he successfully impersonated a German journalist. His whole future life was tied to this country thereafter, and it was there that he met his end.

His intelligent and amicable manner allowed Richard Sorge to easily befriend people. One of the most important among them was the German ambassador to Japan, Major General Eugen Ott, who had access to all the secrets of Nazi Germany.

Ott completely trusted Sorge, and in fact was the main source of all important information for the Soviet intelligence officer. Ott often shared info and asked Sorge’s advice, since he thought Richard Sorge worked for the German intelligence service, having no idea who Sorge’s real paymasters were…

Richard Sorge’s other major source was Japanese journalist Hotsumi Ozaki. An advisor to Prime Minister Fumimaro Konoe, he was a devoted communist and Sorge’s agent, who had access to the highest ranks of Imperial Japan.

Despite the important and useful information Sorge sent to Moscow, the Soviet leadership was very suspicious of their intelligence officer in Japan. A German, with a passion for women and alcohol, with such friends as Nazi Foreign Minister Joachim von Ribbentrop, Sorge was viewed by the Soviets as a double agent.

Still, to gain a spy net in such a closed country as Japan was no easy task, and the Soviet leaders had no choice but to keep Richard Sorge as their main source in the Land of the Rising Sun.

During the series of repressions in the USSR in the late 1930s, known as the Great Purge, Soviet intelligence was literally decapitated, with all its leaders executed, including close colleagues and friends of Sorge. He himself was summoned to Moscow for “talks.”

Afraid for his life, Richard Sorge refused to go, saying he had too much work to do in Japan. This enraged Stalin, who became even more suspicious of “that German.”

These suspicions remained despite the fact that Sorge’s reports significantly helped the Soviet troops to prepare and defeat the Japanese at the Battles of Lake Khasan (1938) and Khalkhin Gol (1939).

Despite being thousands kilometers away from Europe, Richard Sorge had perfect ties with German and Japanese high officials and was sometimes better informed about what was happening there than other Soviet intelligence officers in Europe.

Numerous times Richard Sorge warned his chiefs about German plans to attack the Soviet Union in late June 1941. Yet such reports were ignored.

When Sorge was arrested by the Japanese, he said during the interrogation: “There were days when I sent 3-4 encryptions to Moscow, but, it seems, nobody believed me.”

The attitude towards Sorge completely changed after the launch of Operation Barbarossa confirmed his words. Richard Sorge finally won Stalin’s trust.

On 14 September 1941, Sorge sent perhaps the most important message in his life. “According to my source, the Japanese leadership decided not to begin hostilities against the Soviet Union this year.”

This time Richard Sorge’s words were taken seriously. It is believed that this message finally convinced Stalin to order the redeployment of over a dozen fresh, well-trained divisions from the Far East in defense of Moscow, where they became game-changers.

On December 5, the strengthened Soviet troops went on the counteroffensive and threw the Germans back from the Soviet capital. The Wehrmacht suffered its first serious defeat in the war.

In October 1941, Richard Sorge and his entire group were arrested by the Japanese. At first, the Germans didn’t believe that Richard Sorge, who was proclaimed the best German journalist that year, was a Soviet spy. All their requests to free him were denied.

After Sorge’s work for Soviet intelligence was confirmed, the Japanese twice contacted the Soviets regarding his future fate. Both times the Soviet side answered the same: “We in the Soviet Union know nothing about any such person as Richard Sorge.”

Although it remains unknown as to the precise reason why the Soviets declined to exchange Sorge, it is believed that Stalin could not forgive him for acknowledging his work for the USSR under interrogation, something a Soviet intelligence officer should never do.

When Stalin abandoned his best intelligent officer, Sorge was doomed. As a taunt over the Russians, the Japanese hanged him on November 7, 1944, the 27th anniversary of the Russian Revolution.

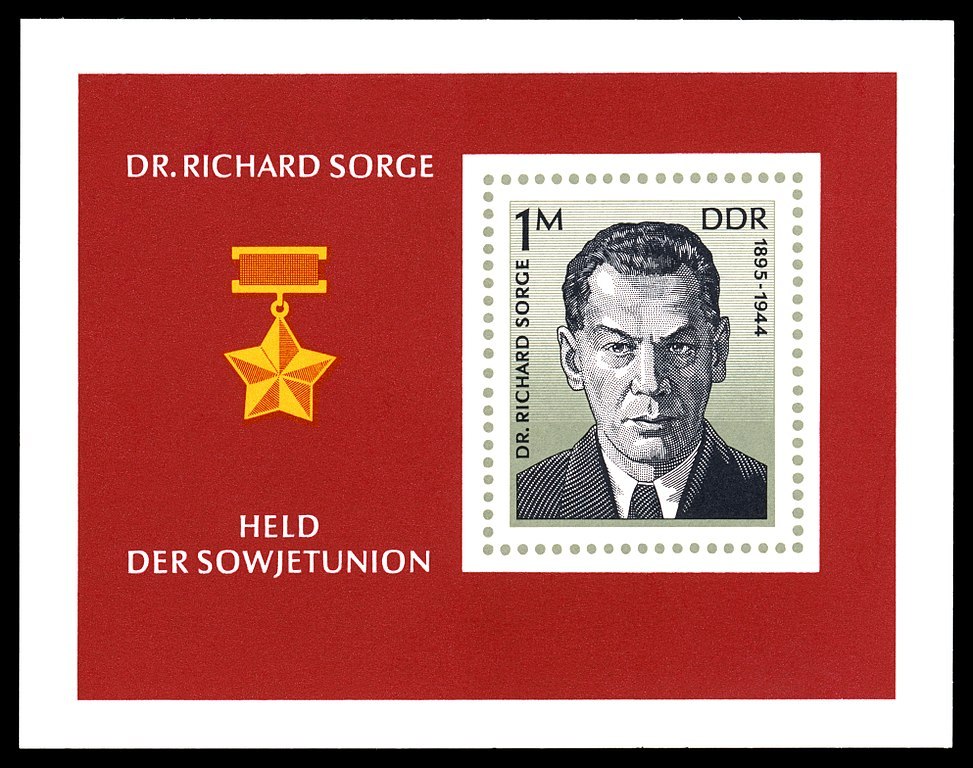

For 20 years the name of Richard Sorge was forgotten in the Soviet Union. But in the U.S. and Europe, quite the opposite, his activity was well studied. In 1964, Nikita Khrushchev saw the French movie Who Are You, Mr. Sorge? and was shocked by what he saw.

When Khrushchev found out that Richard Sorge was a real person, he ordered the name and fame of the Soviet intelligence officer to be restored. Sorge was posthumously awarded the Hero of the Soviet Union.