How should one interpret the Bible? What rules should govern our exegesis? One approach is to tow the party line, a kind of exegetical “be true to your school” approach. This approach looks not primarily to the Biblical text itself, but to one’s ecclesiastical confession, and then reads what that confession says into the text.

For example, a Lutheran might approach the Biblical text of Romans through the confessional lens of the Augsburg Confession and conclude that Paul is there teaching justification by faith alone, exactly (and coincidentally) like Martin Luther would later teach.

Scholars today are unanimous that this is not an adequate or respectful way of dealing with Holy Scripture. Of course one believes what one’s church teaches and of course nothing like complete objectivity is possible. But one should nonetheless strive as best one can to set aside or at least turn down the volume of (say) the Augsburg Confession while one is exegeting the Biblical text and try to read the text on its own terms.

When reading Romans, one listens for the voice of St. Paul, not for the voice of Martin Luther. It is important to realize that “reading the text on its own terms” involves reading the text in its original cultural context. Thus one reads Romans knowing that it was written by a first-century Jew, not a sixteenth-century Catholic.

The task of turning down the volume of one’s confessional statements while exegeting the Bible is easy if one has no such confessional allegiance to those documents. The task is correspondingly difficult the more one gives one’s allegiance to those documents and confessions.

In the case of Orthodoxy, it can be difficult indeed, because our documents and confessions—the Church Fathers, or the consensus patrum—are the lens through which we read the Scriptures. This does not mean that we cannot or should not try to read the Scriptures on their own terms. It just means that for us the exegetical task is more complicated.

For some people, fidelity to the Fathers seems to mean effectively junking the idea of a scholarly reading the Scriptures in their original context and taking the “be true to your (patristic) school” approach. It is certainly an easy way to go. It saves one the work of investigating the cultural background in which the Scriptures were set and allows one to jump straight to the patristic conclusion.

I don’t need to determine how ancient Israelites would have read the text; I just need to read what St. Basil wrote (or perhaps Seraphim Rose’s take on what St. Basil wrote). But fidelity to the Fathers means more than simply agreeing with their exegetical conclusions.

It also means participating in their spirit and phronema, and reading the Scriptures with the same trembling respect that they did. It is this trembling respect that we bring to our exegesis when we insist on reading the Bible in its original cultural context.

Perhaps an example might be helpful. Take what is arguably one of the most famous lines in the Bible, “And God said, ‘Let us make man in our image, after our likeness’” (Genesis 1:26). One asks, “Given the monotheism presupposed in the Book of Genesis, why the plurals? Why did God say, ‘Let us make man in our image’ rather than ‘Let me make man in my image?’ What do such plurals mean in the Old Testament?”

If we read Scripture on its own terms, we must begin by asking the question, “How would the original readers/ hearers of this passage have understood by it?” A refusal to ask this italicized question constitutes a refusal to situate the Scriptures in its own cultural context. It is true that for Christians this context cannot be the place we finish (Christ is where we finish, since He is the telos of the Law; Romans 10:4), but it must be the place from which we start.

As Orthodox in our exegesis we must end with Christ and the Fathers, but we cannot begin there. Exegetically we begin with the original hearers of the texts.

So, beginning in the time in which Genesis was written and read, we must ask, “How would the original readers of this text have understood the plurals? Are there any other times when God found Himself (as it were) not alone in heaven?”

There are indeed a few instances of such plural usage. In Isaiah 6:8, Isaiah “heard the voice of the Lord saying, ‘Whom shall I send, and who will go for us?’” (The Greek Septuagint was apparently a little embarrassed at the plural, for it rendered it, “Whom shall I send, and who will go to this people?”) Who was God addressing here? Was it simply that He was using what is called “the plural of majesty”, as Queen Elizabeth once did when she famously said, “We are not amused”?

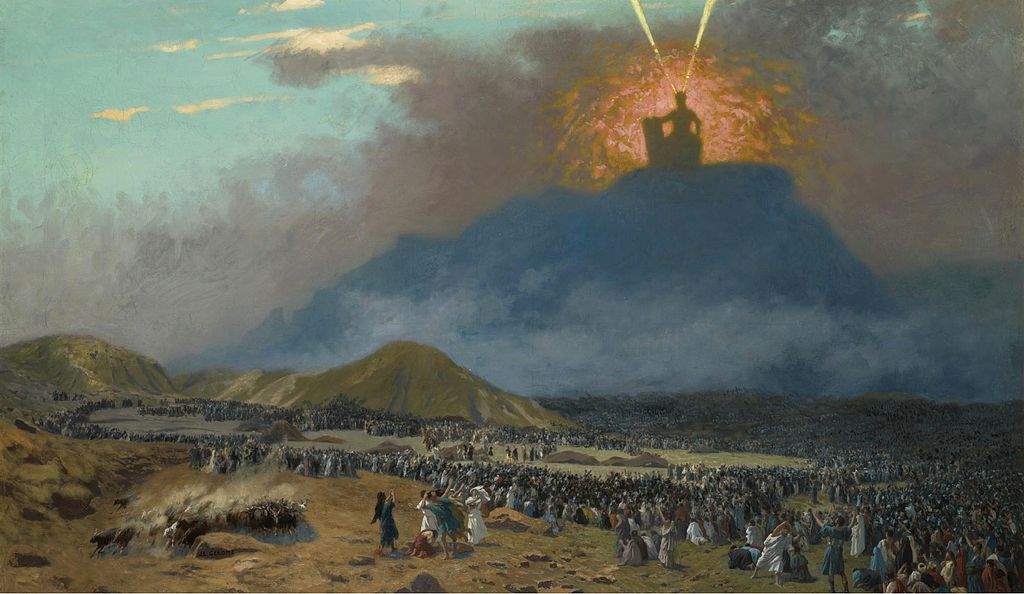

We can begin to find an answer by looking at other passages in the Old Testament. In 1 Kings 22, the prophet Micaiah said that he “saw Yahweh sitting on this throne, and all the host of heaven standing beside him on his right hand and on his left, and Yahweh said, ‘Who will entice Ahab that he may go up and fall at Ramoth-gilead?’”

This reference to Yahweh’s divine council is reflected in other Old Testament passages as well. In Job 1:6 we read of the “sons of God” (i.e. the angels) coming to present themselves before Yahweh and Yahweh conversing with them, and in Job 38:7 we read of the sons of God cheering when He first made the world. These “sons of God” are exhorted to ascribe glory and strength to Yahweh in Psalm 29:1.

In Psalm 82:1 the Psalmist says that God has taken His place “in the congregation of God [Hebrew el], in the midst of the gods [Hebrew elohim] He holds judgment”. These “gods” (Hebrew elohim) were clearly His angels, the “sons of God” (Hebrew bene ha-elohim) Job 1:6. In Psalm 89:5-7, we read the same thing: “Let the heavens praise Your wonders, O Yahweh, Your faithfulness in the assembly of the holy ones! For who in the sky can be compared to Yahweh? Who among the sons of gods [Hebrew bene elim] is like Yahweh, a God [Hebrew el] feared in the council of the holy ones?”

The idea that a god acted in council and concert with the other gods was common in Mesopotamia. What we have here in the Old Testament is the monotheistic transformation of that cultural commonplace. There is no other deity except Yahweh. His council consists not of fellow-deities, but simply of lesser beings, angels, “sons of gods”.

But the idea that the king always has his council, whether an earthly king or Yahweh the King of heaven, was assumed in both pagan Mesopotamia and monotheistic Israel. It seems clear that it was to this council that Yahweh spoke and referred when making momentous decisions, whether those decisions involved enticing Ahab, sending a prophet like Isaiah to Judah, or creating man in His own image.

The picture of the divine counsel offering input is anthropomorphic, to be sure, as are pictures of Yahweh baring His arm in the sight of the nations, rolling up His divine sleeves before working to redeem Israel (Isaiah 52:10). It constitutes more a cultural backdrop to Yahweh’s acts than it does Scripture’s main message. But it is just this cultural backdrop that we find in Genesis 1:26.

That is where we must begin our exegesis, for that is how the original hearers, long familiar with the concept of Yahweh addressing His council, would have heard it. But although we begin there, we do not end there. All the teaching of the Old Testament forms a pedagogical trajectory, for the Law was a pedagogue to bring us to Christ (Galatians 3:24).

Taught by our Trinitarian experience of the grace of Christ, we ask about the sensus plenior, the deeper hidden meaning of the text. Why did the Hebrew Scriptures preserve such images as God’s divine council, with the resultant use of plurals? Historically this was clearly a cultural vestige of the common Middle Eastern picture of deity. But prophetically it serves as a foreshadowing of the tri-personal God.

The richness of reality that led the ancient authors to speak of a divine council (and in Israel to also use a plural name for God, viz. Elohim) would eventually find fulfillment in our understanding of God as Trinity. If one follows this trajectory of divine majesty it leads us in the end to the insights of the Fathers—in other words, it leads us to Christ.

The ancient instinct was that Yahweh was too great, powerful, and transcendent to be a solitary Monad in the Middle Eastern sky. Just as a king must have his council to be a true king, so Yahweh was too glorious not to be attended by the council of His holy ones. This is why the Old Testament texts spoke of other gods (Hebrew elim) even when they asserted Yahweh’s unique monotheistic status. And this instinct was not wrong.

Later on we discovered that God is indeed too great, powerful, and transcendent to be a solitary Monad. He was Trinity, bursting the bonds of solitary personhood in the effulgence of tri-personal deity. And the roots of this concept found initial and faint adumbration in those Old Testament plurals, as well as in the mysterious references to “the angel of Yahweh”.

One need not therefore toe the party line and shrink from reading the Old Testament in its cultural context. Such a cultural reading is not preferring “Jewish interpretations” to Christian ones as some might think. It is only recognizing that Judaism came before Christianity and the Old Testament before the New.

It is also preferring scholarship to partisanship, for the scholars who recognize that the plurals of Genesis 1:26 refer to Yahweh’s divine council are Christians (e.g. John Walton who teaches at Wheaton, and the authors of the Cultural Backgrounds Study Bible). It might be a Jewish interpretation if we stopped in the Old Testament and refused to see that interpretation as one stage in a trajectory that leads ultimately to Christ or denied the Holy Trinity.

But in fact we do not stop there, but go on from the Old Testament interpretation to find the richer sensus plenior in all the Old Testament. This fuller meaning of the text, so well expressed by the Fathers, is its highest meaning, and that which is of most use to us in our walk with God.

In this sense we must begin with the Fathers, in that they reveal Scriptures fullest meaning and the destination to which the Old Testament trajectories are leading.

But the highest does not stand without the lowest, and we must first understand the Old Testament as the message of God to Israel before we can understand it as the message of God to His Church.

If we insist on beginning at the end of our exegetical journey and confuse the sensus plenior for the original sensus, we are poor scholars and show unintentional disrespect for the Scriptures. Exegetical anachronism is not the way to go. If the Fathers teach us anything, they teach us that we must hear what the Scriptures have to say and that we must read them on our knees.

The photo shows, “The Magdalene Reading,” by Rogier van der Weyden, painted before 1438.