I.

To the modern Englishman Handel is almost a contemporary. Paintings and busts of this great minstrel are scattered everywhere throughout the land. He lies in Westminster Abbey among the great poets, warriors, and statesmen, a giant memory in his noble art. A few hours after death the sculptor Roubiliac took a cast of his face, which he wrought into imperishable marble; “moulded in colossal calm,” he towers above his tomb, and accepts the homage of the world benignly like a god. Exeter Hall and the Foundling Hospital in London are also adorned with marble statues of him.

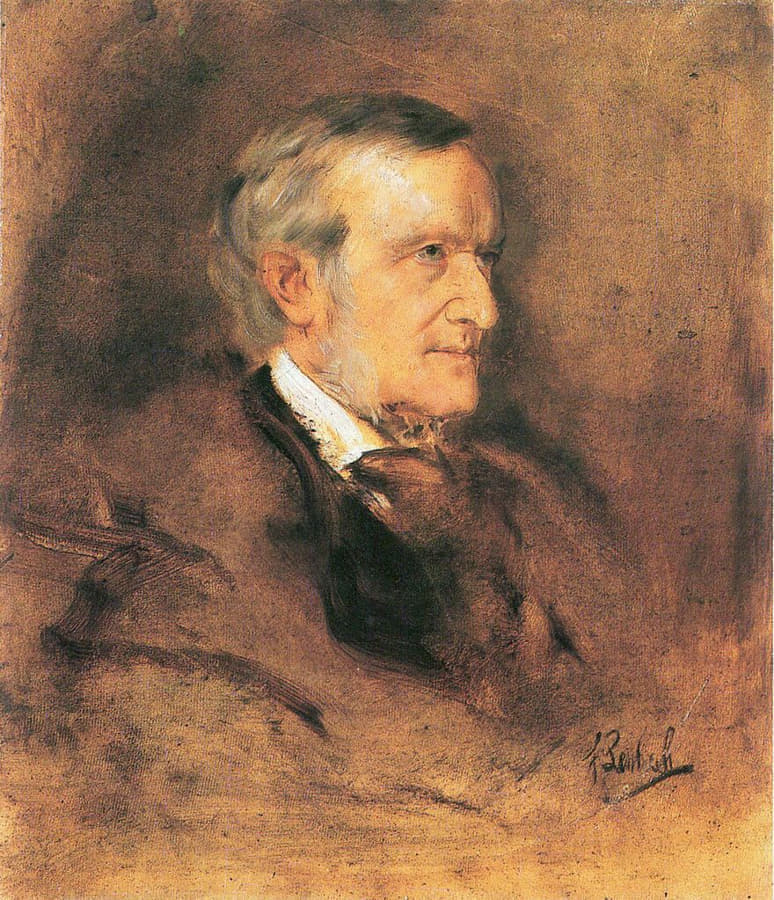

There are more than fifty known pictures of Handel, some of them by distinguished artists. In the best of these pictures Handel is seated in the gay costume of the period, with sword, shot-silk breeches, and coat embroidered with gold. The face is noble in its repose. Benevolence is seated about the finely-shaped mouth, and the face wears the mellow dignity of years, without weakness or austerity. There are few collectors of prints in England and America who have not a woodcut or a lithograph of him. His face and his music are alike familiar to the English-speaking world.

Handel came to England in the year 1710, at the age of twenty-five. Four years before he had met, at Naples, Scarlatti, Porpora, and Corelli. That year had been the turning-point in his life. With one stride he reached the front rank, and felt that no musician alive could teach him anything.

George Frederick Handel (or Handel, as the name is written in German) was born at Halle, Lower Saxony, in the year 1685. Like German literature, German music is a comparatively recent growth. What little feeling existed for the musical art employed itself in cultivating the alien flowers of Italian song. Even eighty years after this Mozart and Haydn were treated like lackeys and vagabonds, just as great actors were treated in England at the same period. Handel’s father looked on music as an occupation having very little dignity.

Determined that his young son should become a doctor like himself, and leave the divine art to Italian fiddlers and French buffoons, he did not allow him to go to a public school even, for fear he should learn the gamut. But the boy Handel, passionately fond of sweet sounds, had, with the connivance of his nurse, hidden in the garret a poor spinet, and in stolen hours taught himself how to play. At last the senior Handel had a visit to make to another son in the service of the Duke of Saxe-Weissenfels, and the young George was taken along to the ducal palace. The boy strayed into the chapel, and was irresistibly drawn to the organ. His stolen performance was made known to his father and the duke, and the former was very much enraged at such a direct evidence of disobedience. The duke, however, being astonished at the performance of the youthful genius, interceded for him, and recommended that his taste should be encouraged and cultivated instead of repressed.

From this time forward fortune showered upon him a combination of conditions highly favorable to rapid development. Severe training, ardent friendship, the society of the first composers, and incessant practice were vouchsafed him. As the pupil of the great organist Zachau, he studied the whole existing mass of German and Italian music, and soon exacted from his master the admission that he had nothing more to teach him. Thence he went to Berlin to study the opera-school, where Ariosti and Bononcini were favorite composers. The first was friendly, but the latter, who with a first-rate head had a cankered heart, determined to take the conceit out of the Saxon boy. He challenged him to play at sight an elaborate piece. Handel played it with perfect precision, and thenceforward Bononcini, though he hated the youth as a rival, treated him as an equal.

On the death of his father Handel secured an engagement at the Hamburg opera-house, where he soon made his mark by the ability with which, on several occasions, he conducted rehearsals.

At the age of nineteen Handel received the offer of the Lübeck organ, on condition that he would marry the daughter of the retiring organist. He went down with his friend Mattheson, who it seems had been offered the same terms. They both returned, however, in single blessedness to Hamburg.

Though the Lübeck maiden had stirred no bad blood between them, musical rivalry did. A dispute in the theatre resulted in a duel. The only thing that saved. Handel’s life was a great brass button that shivered his antagonist’s point, when they were parted to become firm friends again.

While at Hamburg Handel’s first two operas were composed, “Almira” and “Nero.” Both of these were founded on dark tales of crime and sorrow, and, in spite of some beautiful airs and clever instrumentation, were musical failures, as might be expected.

Handel had had enough of manufacturing operas in Germany, and so in July, 1706, he went to Florence. Here he was cordially received; for Florence was second to no city in Italy in its passion for encouraging the arts. Its noble specimens of art creations in architecture, painting, and sculpture, produced a powerful impression upon the young musician. In little more than a week’s time he composed an opera, “Rodrigo,” for which he obtained one hundred sequins. His next visit was to Venice, where he arrived at the height of the carnival. Whatever effect Venice, with its weird and mysterious beauty, with its marble palaces, façades, pillars, and domes, its magnificent shrines and frescoes, produced on Handel, he took Venice by storm. Handel’s power as an organist and a harpsichord player was only second to his strength as a composer, even when, in the full zenith of his maturity, he composed the “Messiah” and “Judas Maccabæus.”

“Il caro Sassone,” the dear Saxon, found a formidable opponent as well as dear friend in the person of Scarlatti. One night at a masked ball, given by a nobleman, Handel was present in disguise. He sat at the harpsichord, and astonished the company with his playing; but no one could tell who it was that ravished the ears of the assembly. Presently another masquerader came into the room, walked up to the instrument, and called out: “It is either the devil or the Saxon!” This was Scarlatti, who afterward had with Handel, in Florence and Rome, friendly contests of skill, in which it seemed difficult to decide which was victor. To satisfy the Venetian public, Handel composed the opera “Agrippina,” which made a furore among all the connoisseurs of the city.

So, having seen the summer in Florence and the carnival in Venice, he must hurry on to be in time for the great Easter celebrations in Rome. Here he lived under the patronage of Cardinal Otto-boni, one of the wealthiest and most liberal of the Sacred College. The cardinal was a modern representative of the ancient patrician. Living himself in princely luxury, he endowed hospitals and surgeries for the public. He distributed alms, patronized men of science and art, and entertained the public with comedies, operas, oratorios, puppet-shows, and academic disputes. Under the auspices of this patron, Handel composed three operas and two oratorios. Even at this early period the young composer was parting company with the strict old musical traditions, and his works showed an extraordinary variety and strength of treatment.

From Rome he went to Naples, where he spent his second Italian summer, and composed the original Italian “Aci e Galatea,” which in its English version, afterward written for the Duke of Chandos, has continued a marked favorite with the musical world. Thence, after a lingering return through the sunny land where he had been so warmly welcomed, and which had taught him most effectually, in convincing him that his musical life had nothing in common with the traditions of Italian musical art, he returned to Germany, settling at the court of George of Brunswick, Elector of Hanover, and afterward King of England. He received commission in the course of a few months from the elector to visit England, having been warmly invited thither by some English noblemen. On his return to Hanover, at the end of six months, he found the dull and pompous little court unspeakably tiresome after the bustle of London. So it is not to be marveled at that he took the earliest opportunity of returning to the land which he afterward adopted. At this period he was not yet twenty-five years old, but already famous as a performer on the organ and harpsichord, and as a composer of Italian operas.

When Queen Anne died and Handel’s old patron became King of England, Handel was forbidden to appear before him, as he had not forgotten the musician’s escapade; but his peace was at last made by a little ruse. Handel had a friend at court, Baron Kilmansegge, from whom he learned that the king was, on a certain day, going to take an excursion on the Thames. So he set to work to compose music for the occasion, which he arranged to have performed on a boat which followed the king’s barge. As the king floated down the river he heard the new and delightful “Water-Music.” He knew that only one man could have composed such music; so he sent for Handel, and sealed his pardon with a pension of two hundred pounds a year.

II.

Let us take a glance at the society in which the composer moved in the heyday of his youth. His greatness was to be perfected in after-years by bitter rivalries, persecution, alternate oscillations of poverty and affluence, and a multitude of bitter experiences. But at this time Handel’s life was a serene and delightful one. Rival factions had not been organized to crush him. Lord Burlington lived much at his mansion, which was then out of town, although the house is now in the heart of Piccadilly. The intimate friendship of this nobleman helped to bring the young musician into contact with many distinguished people.

It is odd to think of the people Handel met daily without knowing that their names and his would be in a century famous. The following picture sketches Handel and his friends in a sprightly fashion:

“Yonder heavy, ragged-looking youth standing at the corner of Regent Street, with a slight and rather more refined-looking companion, is the obscure Samuel Johnson, quite unknown to fame. He is walking with Richard Savage. As Signor Handel, ‘the composer of Italian music,’ passes by, Savage becomes excited, and nudges his friend, who takes only a languid interest in the foreigner. Johnson did not care for music; of many noises he considered it the least disagreeable.

“Toward Charing Cross comes, in shovel-hat and cassock, the renowned ecclesiastic Dean Swift. He has just nodded patronizingly to Bononcini in the Strand, and suddenly meets Handel, who cuts him dead. Nothing disconcerted, the dean moves on, muttering his famous epigram:

'Some say that Signor Bononcini,

Compared to Handel, is a ninny;

While others vow that to him Handel

Is hardly fit to hold a candle.

Strange that such difference should be

'Twixt tweedledum and tweedledee.'

“As Handel enters the ‘Turk’s Head’ at the corner of Regent Street, a noble coach and four drives up. It is the Duke of Chandos, who is inquiring for Mr. Pope. Presently a deformed little man, in an iron-gray suit, and with a face as keen as a razor, hobbles out, makes a low bow to the burly Handel, who, helping him into the chariot, gets in after him, and they drive off together to Cannons, the duke’s mansion at Edge-ware. There they meet Mr. Addison, the poet Gay, and the witty Arbuthnot, who have been asked to luncheon. The last number of the Spectator is on the table, and a brisk discussion soon arises between Pope and Addison concerning the merits of the Italian opera, in which Pope would have the better if he only knew a little more about music, and could keep his temper. Arbuthnot sides with Pope in favor of Mr. Handel’s operas; the duke endeavors to keep the peace. Handel probably uses his favorite exclamation, ‘Vat te tevil I care!’ and consumes the recherche wines and rare viands with undiminished gusto.

“The Magnificent, or the Grand Duke, as he was called, had built himself a palace for £230,000. He had a private chapel, and appointed Handel organist in the room of the celebrated Dr. Pepusch, who retired with excellent grace before one manifestly his superior. On week-days the duke and duchess entertained all the wits and grandees in town, and on Sundays the Edgeware Road was thronged with the gay equipages of those who went to worship at the ducal chapel and hear Mr. Handel play on the organ.

“The Edgeware Road was a pleasant country drive, but parts of it were so solitary that highwaymen were much to be feared. The duke was himself attacked on one occasion; and those who could afford it never traveled so far out of town without armed retainers. Cannons was the pride of the neighborhood, and the duke—of whom Pope wrote,

'Thus gracious Chandos is beloved at sight'—

was as popular as he was wealthy. But his name is made still more illustrious by the Chandos anthems. They were all written at Cannons between 1718 and 1720, and number in all eleven overtures, thirty-two solos, six duets, a trio, quartet, and forty-seven choruses. Some of the above are real masterpieces; but, with the exception of ‘The waves of the sea rage horribly,’ and ‘Who is God but the Lord?’ few of them are ever heard now. And yet these anthems were most significant in the variety of the choruses and in the range of the accompaniments; and it was then, no doubt, that Handel was feeling his way toward the great and immortal sphere of his oratorio music. Indeed, his first oratorio, ‘Esther,’ was composed at Cannons, as also the English version of ‘Acis and Galatea.'”

But Handel had other associates, and we must now visit Thomas Britton, the musical coal-heaver. “There goes the famous small-coal man, a lover of learning, a musician, and a companion of gentlemen.” So the folks used to say as Thomas Britton, the coal-heaver of Clerkenwell Green, paced up and down the neighboring streets with his sack of small coal on his back, destined for one of his customers. Britton was great among the great. He was courted by the most fashionable folk of his day. He was a cultivated coal-heaver, who, besides his musical taste and ability, possessed an extensive knowledge of chemistry and the occult sciences.

Britton did more than this. He gave concerts in Aylesbury Street, Clerkenwell, where this singular man had formed a dwelling-house, with a concert-room and a coal-store, out of what was originally a stable. On the ground-floor was the small-coal repository, and over that the concert-room—very long and narrow, badly lighted, and with a ceiling so low that a tall man could scarcely stand upright in it. The stairs to this room were far from pleasant to ascend, and the following facetious lines by Ward, the author of the “London Spy,” confirm this:

"Upon Thursdays repair

To my palace, and there

Hobble up stair by stair

But I pray ye take care

That you break not your shins by a stumble;

"And without e'er a souse

Paid to me or my spouse,

Sit as still as a mouse

At the top of the house,

And there you shall hear how we fumble."

Nevertheless beautiful duchesses and the best society in town flocked to Britton’s on Thursdays—not to order coals, but to sit out his concerts.

Let us follow the short, stout little man on a concert-day. The customers are all served, or as many as can be. The coal-shed is made tidy and swept up, and the coal-heaver awaits his company. There he stands at the door of his stable, dressed in his blue blouse, dustman’s hat, and maroon kerchief tightly fastened round his neck. The concert-room is almost full, and, pipe in hand, Britton awaits a new visitor—the beautiful Duchess of B———. She is somewhat late (the coachman, possibly, is not quite at home in the neighborhood).

Here comes a carriage, which stops at the coal-shop; and, laying down his pipe, the coal-heaver assists her grace to alight, and in the genteelest manner escorts her to the narrow staircase leading to the music-room. Forgetting Ward’s advice, she trips laughingly and carelessly up the stairs to the room, from which proceed faint sounds of music, increasing to quite an olla podri-da of sound as the apartment is reached—for the musicians are tuning up. The beautiful duchess is soon recognized, and as soon in deep gossip with her friends. But who is that gentlemanly man leaning over the chamber-organ? That is Sir Roger L’Estrange, an admirable performer on the violoncello, and a great lover of music. He is watching the subtile fingering of Mr. Handel, as his dimpled hands drift leisurely and marvelously over the keys of the instrument.

There, too, is Mr. Bannister with his fiddle—the first Englishman, by-the-by, who distinguished himself upon the violin; there is Mr. Woolaston, the painter, relating to Dr. Pepusch of how he had that morning thrown up his window upon hearing Britton crying “Small coal!” near his house in Warwick Lane, and, having beckoned him in, had made a sketch for a painting of him; there, too, is Mr. John Hughes, author of the “Siege of Damascus.” In the background also are Mr. Philip Hart, Mr. Henry Symonds, Mr. Obadiah Shuttleworth, Mr. Abiell Whichello; while in the extreme corner of the room is Robe, a justice of the peace, letting out to Henry Needier of the Excise Office the last bit of scandal that has come into his court. And now, just as the concert has commenced, in creeps “Soliman the Magnificent,” also known as Mr. Charles Jennens, of Great Ormond Street, who wrote many of Handel’s librettos, and arranged the words for the “Messiah.”

“Soliman the Magnificent” is evidently resolved to do justice to his title on this occasion with his carefully-powdered wig, frills, maroon-colored coat, and buckled shoes; and as he makes his progress up the room, the company draw aside for him to reach his favorite seat near Handel. A trio of Corelli’s is gone through; then Madame Cuzzoni sings Handel’s last new air; Dr. Pepusch takes his turn at the harpsichord; another trio of Hasse, or a solo on the violin by Bannister; a selection on the organ from Mr. Handel’s new oratorio; and then the day’s programme is over.

Dukes, duchesses, wits and philosophers, poets and musicians, make their way down the satirized stairs to go, some in carriages, some in chairs, some on foot, to their own palaces, houses, or lodgings.

III.

We do not now think of Handel in connection with the opera. To the modern mind he is so linked to the oratorio, of which he was the father and the consummate master, that his operas are curiosities but little known except to musical antiquaries. Yet some of the airs from the Handel operas are still cherished by singers as among the most beautiful songs known to the concert-stage.

In 1720 Handel was engaged by a party of noblemen, headed by his Grace of Chandos, to compose operas for the Royal Academy of Music at the Haymarket. An attempt had been made to put this institution on a firm foundation by a subscription of £50,000, and it was opened on May 2d with a full company of singers engaged by Handel. In the course of eight years twelve operas were produced in rapid succession: “Floridante,” December 9, 1721; “Ottone,” January 12, 1723; “Flavio” and “Giulio Cesare,” 1723; “Tamerlano,” 1724; “Rodelinda,” 1725; “Scipione,” 1726; “Alessandro,” 1726; “Admeto,” 727; “Siroe,” 1728; and “Tolommeo,” 1728. They made as great a furore among the musical public of that day as would an opera from Gounod or Verdi in the present. The principal airs were sung throughout the land, and published as harpsichord pieces; for in these halcyon days of our composers the whole atmosphere of the land was full of the flavor and color of Handel. Many of the melodies in these now forgotten operas have been worked up by modern composers, and so have passed into modern music unrecognized. It is a notorious fact that the celebrated song, “Where the Bee sucks,” by Dr. Arne, is taken from a movement in “Rinaldo.” Thus the new life of music is ever growing rich with the dead leaves of the past. The most celebrated of these operas was entitled “Otto.” It was a work composed of one long string of exquisite gems, like Mozart’s “Don Giovanni” and Gounod’s “Faust.” Dr. Pepusch, who had never quite forgiven Handel for superseding him as the best organist in England, remarked, of one of the airs, “That great bear must have been inspired when he wrote that air.” The celebrated Madame Cuzzoni made her début in it. On the second night the tickets rose to four guineas each, and Cuzzoni received two thousand pounds for the season.

The composer had already begun to be known for his irascible temper. It is refreshing to learn that operatic singers of the day, however whimsical and self-willed, were obliged to bend to the imperious genius of this man. In a spirit of ill-timed revolt Cuzzoni declined to sing an air. She had already given him trouble by her insolence and freaks, which at times were unbearable. Handel at last exploded. He flew at the wretched woman and shook her like a rat. “Ah! I always knew you were a fery tevil,” he cried, “and I shall now let you know that I am Beelzebub, the prince of de tevils!” and, dragging her to the open window, was just on the point of pitching her into the street when, in every sense of the word, she recanted. So, when Carestini, the celebrated tenor, sent back an air, Handel was furious. Rushing into the trembling Italian’s house, he said, in his four- or five-language style: “You tog! don’t I know better as yourself vaat it pest for you to sing? If you vill not sing all de song vaat I give you, I vill not pay you ein stiver.” Among the anecdotes told of Handel’s passion is one growing out of the composer’s peculiar sensitiveness to discords. The dissonance of the tuning-up period of an orchestra is disagreeable to the most patient. Handel, being peculiarly sensitive to this unfortunate necessity, always arranged that it should take place before the audience assembled, so as to prevent any sound of scraping or blowing. Unfortunately, on one occasion, some wag got access to the orchestra where the ready-tuned instruments were lying, and with diabolical dexterity put every string and crook out of tune. Handel enters. All the bows are raised together, and at the given beat all start off con spirito. The effect was startling in the extreme. The unhappy maestro rushes madly from his place, kicks to pieces the first double-bass he sees, and, seizing a kettle-drum, throws it violently at the leader of the band. The effort sends his wig flying, and, rushing bareheaded to the footlights, he stands a few moments amid the roars of the house, snorting with rage and choking with passion. Like Burleigh’s nod, Handel’s wig seemed to have been a sure guide to his temper. When things went well, it had a certain complacent vibration; but when he was out of humor, the wig indicated the fact in a very positive way. The Princess of Wales was wont to blame her ladies for talking instead of listening. “Hush, hush!” she would say. “Don’t you see Handel’s wig?”

For several years after the subscription of the nobility had been exhausted, our composer, having invested £10,000 of his own in the Haymarket, produced operas with remarkable affluence, some of them pasticcio works, composed of all sorts of airs, in which the singers could give their bravura songs. These were “Lotario,” 1729; “Partenope,” 1730; “Poro,” 1731; “Ezio,” 1732; “Sosarme,” 1732; “Orlando,” 1733; “Ariadne,” 1734; and also several minor works. Handel’s operatic career was not so much the outcome of his choice as dictated to him by the necessity of time and circumstance. As time went on, his operas lost public interest. The audiences dwindled, and the overflowing houses of his earlier experience were replaced by empty benches. This, however, made little difference with Handel’s royal patrons. The king and the Prince of Wales, with their respective households, made it an express point to show their deep interest in Handel’s success. In illustration of this, an amusing anecdote is told of the Earl of Chesterfield. During the performance of “Rinaldo” this nobleman, then an equerry of the king, was met quietly retiring from the theatre in the middle of the first act. Surprise being expressed by a gentleman who met the earl, the latter said: “I don’t wish to disturb his Majesty’s privacy.”

Handel paid his singers in those days what were regarded as enormous prices. Senisino and Carestini had each twelve hundred pounds, and Cuzzoni two thousand, for the season. Toward the end of what may be called the Handel season nearly all the singers and nobles forsook him, and supported Farinelli, the greatest singer living, at the rival house in Lincoln’s Inn Fields.

IV.

From the year 1729 the career of Handel was to be a protracted battle, in which he was sometimes victorious, sometimes defeated, but always undaunted and animated with a lofty sense of his own superior power. Let us take a view of some of the rival musicians with whom he came in contact. Of all these Bononcini was the most formidable. He came to England in 1720 with Ariosti, also a meritorious composer. Factions soon began to form themselves around Handel and Bononcini, and a bitter struggle ensued between these old foes. The same drama repeated itself, with new actors, about thirty years afterward, in Paris. Gluck was then the German hero, supported by Marie Antoinette, and Piccini fought for the Italian opera under the colors of the king’s mistress Du Barry, while all the litterateurs and nobles ranged themselves on either side in bitter contest. The battle between Handel and Bononcini, as the exponents of German and Italian music, was also repeated in after-years between Mozart and Salieri, Weber and Rossini, and to-day is seen in the acrimonious disputes going on between Wagner and the Italian school. Bononcini’s career in England came to an end very suddenly. It was discovered that a madrigal brought out by him was pirated from another Italian composer; whereupon Bononcini left England, humiliated to the dust, and finally died obscure and alone, the victim of a charlatan alchemist, who succeeded in obtaining all his savings.

Another powerful rival of Handel was Porpora, or, as Handel used to call him, “old Borbora.” Without Bononcini’s fire or Handel’s daring originality, he represented the dry contrapuntal school of Italian music. He was also a great singing-master, famous throughout Europe, and upon this his reputation had hitherto principally rested. He came to London in 1733, under the patronage of the Italian faction, especially to serve as a thorn in the side of Handel. His first opera, “Ariadne,” was a great success; but when he had the audacity to challenge the great German in the field of oratorio, his defeat was so overwhelming that he candidly admitted his rival’s superiority. But he believed that no operas in the world were equal to his own, and he composed fifty of them during his life, extending to the days of Haydn, whom he had the honor of teaching, while the father of the symphony, on the other hand, cleaned Por-pora’s boots and powdered his wig for him.

Another Italian opponent was Hasse, a man of true genius, who in his old age instructed some of the most splendid singers in the history of the lyric stage. He also married one of the most gifted and most beautiful divas of Europe, Faustina Bordoni. The following anecdote does equal credit to Hasse’s heart and penetration: In after-years, when he had left England, he was again sent for to take Handel’s place as conductor of opera and oratorio. Hasse inquired, “What! is Handel dead?” On being told no, he indignantly refused, saying he was not worthy to tie Handel’s shoe-latchets.

There are also Dr. Pepusch, the Anglicized Prussian, and Dr. Greene, both names well known in English music. Pepusch had had the leading place, before Handel’s arrival, as organist and conductor, and made a distinct place for himself even after the sun of Handel had obscured all of his contemporaries. He wrote the music of the “Beggar’s Opera,” which was the great sensation of the times, and which still keeps possession of the stage. Pepusch was chiefly notable for his skill in arranging the popular songs of the day, and probably did more than any other composer to give the English ballad its artistic form.

The name of Dr. Greene is best known in connection with choral compositions. His relations with Handel and Bononcini are hardly creditable to him. He seems to have flattered each in turn. He upheld Bononcini in the great madrigal controversy, and appears to have wearied Handel by his repeated visits. The great Saxon easily saw through the flatteries of a man who was in reality an ambitious rival, and joked about him, not always in the best taste. When he was told that Greene was giving concerts at the “Devil Tavern,” near Temple Bar, “Ah!” he exclaimed, “mein poor friend Toctor Greene—so he is gone to de Tevil!”

From 1732 to 1740 Handel’s life presents the suggestive and often-repeated experience in the lives of men of genius—a soul with a great creative mission, of which it is half unconscious, partly yielding to and partly struggling against the tendencies of the age, yet gradually crystallizing into its true form, and getting consecrated to its true work. In these eight years Handel presented to the public ten operas and five oratorios. It was in 1731 that the great significant fact, though unrecognized by himself and others, occurred, which stamped the true bent of his genius. This was the production of his first oratorio in England. He was already playing his operas to empty houses, the subject of incessant scandal and abuse on the part of his enemies, but holding his way with steady cheerfulness and courage. Twelve years before this he had composed the oratorio of “Esther,” but it was still in manuscript, uncared for and neglected. It was finally produced by a society called Philharmonic, under the direction of Bernard Gates, the royal chapel-master. Its fame spread wide, and we read these significant words in one of the old English newspapers: “‘Esther,’ an English oratorio, was performed six times, and very full.”

Shortly after this Handel himself conducted “Esther” at the Haymarket by royal command. His success encouraged him to write “Deborah,” another attempt in the same field, and it met a warm reception from the public, March 17, 1733.

For about fifteen years Handel had struggled heroically in the composition of Italian operas. With these he had at first succeeded; but his popularity waned more and more, and he became finally the continued target for satire, scorn, and malevolence. In obedience to the drift of opinion, all the great singers, who had supported him at the outset, joined the rival ranks or left England. In fact it may be almost said that the English public were becoming dissatisfied with the whole system and method of Italian music. Colley Cibber, the actor and dramatist, explains why Italian opera could never satisfy the requirement of Handel, or be anything more than an artificial luxury in England: “The truth is, this kind of entertainment is entirely sensational.” Still both Handel and his friends and his foes, all the exponents of musical opinion in England, persevered obstinately in warming this foreign exotic into a new lease of life.

The quarrel between the great Saxon composer and his opponents raged incessantly both in public and private. The newspaper and the drawing-room rang alike with venomous diatribes. Handel was called a swindler, a drunkard, and a blasphemer, to whom Scripture even was not sacred. The idea of setting Holy Writ to music scandalized the Pharisees, who reveled in the licentious operas and love-songs of the Italian school. All the small wits of the time showered on Handel epigram and satire unceasingly. The greatest of all the wits, however, Alexander Pope, was his firm friend and admirer; and in the “Dunciad,” wherein the wittiest of poets impaled so many of the small fry of the age with his pungent and vindictive shaft, he also slew some of the most malevolent of Handel’s foes.

Fielding, in “Tom Jones,” has an amusing hit at the taste of the period: “It was Mr. Western’s custom every afternoon, as soon as he was drunk, to hear his daughter play on the harpsichord; for he was a great lover of music, and perhaps, had he lived in town, might have passed as a connoisseur, for he always excepted against the finest compositions of Mr. Handel.”

So much had it become the fashion to criticise Handel’s new effects in vocal and instrumental composition, that some years later Mr. Sheridan makes one of his characters fire a pistol simply to shock the audience, and makes him say in a stage whisper to the gallery, “This hint, gentlemen, I took from Handel.”

The composer’s Oxford experience was rather amusing and suggestive. We find it recorded that in July, 1733, “one Handell, a foreigner, was desired to come to Oxford to perform in music.” Again the same writer says: “Handell with his lousy crew, a great number of foreign fiddlers, had a performance for his own benefit at the theatre.” One of the dons writes of the performance as follows: “This is an innovation; but every one paid his five shillings to try how a little fiddling would sit upon him. And, notwithstanding the barbarous and inhuman combination of such a parcel of unconscionable scamps, he [Handel] disposed of the most of his tickets.”

“Handel and his lousy crew,” however, left Oxford with the prestige of a magnificent victory. His third oratorio, “Athaliah,” was received with vast applause by a great audience. Some of his university admirers, who appreciated academic honors more than the musician did, urged him to accept the degree of Doctor of Music, for which he would have to pay a small fee. The characteristic reply was a Parthian arrow: “Vat te tevil I trow my money away for dat vich the blockhead vish’? I no vant!”

V.

In 1738 Handel was obliged to close the theatre and suspend payment. He had made and spent during his operatic career the sum of £10,000 sterling, besides dissipating the sum of £50,000 subscribed by his noble patrons. The rival house lasted but a few months longer, and the Duchess of Marlborough and her friends, who ruled the opposition clique and imported Bononcini, paid £12,000 for the pleasure of ruining Handel. His failure as an operatic composer is due in part to the same causes which constituted his success in oratorio and cantata. It is a little significant to notice that, alike by the progress of his own genius and by the force of conditions, he was forced out of the operatic field at the very time when he strove to tighten his grip on it.

His free introduction of choral and instrumental music, his creation of new forms and remodeling of old ones, his entire subordination of the words in the story to a pure musical purpose, offended the singers and retarded the action of the drama in the eyes of the audience; yet it was by virtue of these unpopular characteristics that the public mind was being moulded to understand and love the form of the oratorio.

From 1734 to 1738 Handel composed and produced a number of operatic works, the principal ones of which were “Alcina,” 1735; “Arminio,” 1737; and “Berenice,” 1737. He also during these years wrote the magnificent music to Dryden’s “Alexander’s Feast,” and the great funeral anthem on the occasion of Queen Caroline’s death in the latter part of the year 1737.

We can hardly solve the tenacity of purpose with which Handel persevered in the composition of operatic music after it had ruined him; but it was still some time before he fully appreciated the true turn of his genius, which could not be trifled with or ignored. In his adversity he had some consolation. His creditors were patient, believing in his integrity. The royal family were his firm friends.

Southey tells us that Handel, having asked the youthful Prince of Wales, then a child, and afterward George the Third, if he loved music, answered, when the prince expressed his pleasure: “A good boy, a good boy! You shall protect my fame when I am dead.” Afterward, when the half-imbecile George was crazed with family and public misfortunes, he found his chief solace in the Waverley novels and Handel’s music.

It is also an interesting fact that the poets and thinkers of the age were Handel’s firm admirers. Such men as Gay, Arbuthnot, Hughes, Colley Cibber, Pope, Fielding, Hogarth, and Smollett, who recognized the deep, struggling tendencies of the times, measured Handel truly. They defended him in print, and never failed to attend his performances, and at his benefit concerts their enthusiastic support always insured him an overflowing house.

The popular instinct was also true to him. The aristocratic classes sneered at his oratorios and complained at his innovations. His music was found to be good bait for the popular gardens and the holiday-makers of the period. Jonathan Tyers was one of the most liberal managers of this class. He was proprietor of Vauxhall Gardens, and Handel (incognito) supplied him with nearly all his music. The composer did much the same sort of thing for Marylebone Gardens, furbishing up old and writing new strains with an ease that well became the urgency of the circumstances.

“My grandfather,” says the Rev. J. Fountagne, “as I have been told, was an enthusiast in music, and cultivated most of all the friendship of musical men, especially of Handel, who visited him often, and had a great predilection for his society. This leads me to relate an anecdote which I have on the best authority. While Marylebone Gardens were flourishing, the enchanting music of Handel, and probably of Arne, was often heard from the orchestra there. One evening, as my grandfather and Handel were walking together and alone, a new piece was struck up by the band. ‘Come, Mr. Fountagne,’ said Handel, ‘let us sit down and listen to this piece; I want to know your opinion about it.’ Down they sat, and after some time the old parson, turning to his companion, said, ‘It is not worth listening to; it’s very poor stuff.’ ‘You are right, Mr. Fountagne,’ said Handel, ‘it is very poor stuff; I thought so myself when I had finished it.’ The old gentleman, being taken by surprise, was beginning to apologize; but Handel assured him there was no necessity, that the music was really bad, having been composed hastily, and his time for the production limited; and that the opinion given was as correct as it was honest.”

VI.

The period of Handel’s highest development had now arrived. For seven years his genius had been slowly but surely maturing, in obedience to the inner law of his being. He had struggled long in the bonds of operatic composition, but even here his innovations showed conclusively how he was reaching out toward the form with which his name was to be associated through all time. The year 1739 was one of prodigious activity. The oratorio of “Saul” was produced, of which the “Dead March” is still recognized as one of the great musical compositions of all time, being one of the few intensely solemn symphonies written in a major key. Several works now forgotten were composed, and the great “Israel in Egypt” was written in the incredibly short space of twenty-seven days. Of this work a distinguished writer on music says: Handel was now fifty-five years old, and had entered, after many a long and weary contest, upon his last and greatest creative period. His genius culminates in the ‘Israel.’ Elsewhere he has produced longer recitatives and more pathetic arias; nowhere has he written finer tenor songs than ‘The enemy said,’ or finer duets than ‘The Lord is a man of war;’ and there is not in the history of music an example of choruses piled up like so many Ossas on Pelions in such majestic strength, and hurled in open defiance at a public whose ears were itching for Italian love-lays and English ballads. In these twenty-eight colossal choruses we perceive at once a reaction against and a triumph over the tastes of the age. The wonder is, not that the ‘Israel’ was unpopular, but that it should have been tolerated; but Handel, while he appears to have been for years driven by the public, had been, in reality, driving them. His earliest oratorio, ‘Il Trionfo del Tempo’ (composed in Italy), had but two choruses; into his operas more and more were introduced, with disastrous consequences; but when, at the zenith of his strength, he produced a work which consisted almost entirely of these unpopular peculiarities, the public treated him with respect, and actually sat out three performances in one season! In addition to these two great oratorios, our composer produced the beautiful music to Dryden’s “St. Cæcilia Ode,” and Milton’s “L’Allegro” and “Il Penseroso.” Henceforth neither praise nor blame could turn Handel from his appointed course. He was not yet popular with the musical dilettanti, but we find no more catering to an absurd taste, no more writing of silly operatic froth.

Our composer had always been very fond of the Irish, and, at the invitation of the lord-lieutenant and prominent Dublin amateurs, he crossed the channel in 1741. He was received with the greatest enthusiasm, and his house became the resort of all the musical people in the city of Dublin. One after another his principal works were produced before admiring audiences in the new Music Hall in Fishamble Street. The crush to hear the “Allegro” and “Penseroso” at the opening performances was so great that the doors had to be closed. The papers declared there never had been seen such a scene before in Dublin.

Handel gave twelve performances at very short intervals, comprising all of his finest works. In these concerts the “Acis and Galatea” and “Alexander’s Feast” were the most admired; but the enthusiasm culminated in the rendition of the “Messiah,” produced for the first time on April 13, 1742. The performance was a beneficiary one in aid of poor and distressed prisoners for debt in the Marshalsea in Dublin. So, by a remarkable coincidence, the first performance of the “Messiah” literally meant deliverance to the captives. The principal singers were Mrs. Cibber (daughter-in-law of Colley Cibber, and afterward one of the greatest actresses of her time), Mrs. Avoglio, and Mr. Dubourg. The town was wild with excitement. Critics, poets, fine ladies, and men of fashion tore rhetoric to tatters in their admiration. A clergyman so far forgot his Bible in his rapture as to exclaim to Mrs. Cibber, at the close of one of her airs, “Woman, for this be all thy sins forgiven thee.” The penny-a-liners wrote that “words were wanting to express the exquisite delight,” etc. And—supreme compliment of all, for Handel was a cynical bachelor—the fine ladies consented to leave their hoops at home for the second performance, that a couple of hundred or so extra listeners might be accommodated. This event was the grand triumph of Handel’s life. Years of misconception, neglect, and rivalry were swept out of mind in the intoxicating delight of that night’s success.

VII.

Handel returned to London, and composed a new oratorio, “Samson,” for the following Lenten season. This, together with the “Messiah,” heard for the first time in London, made the stock of twelve performances. The fashionable world ignored him altogether; the newspapers kept a contemptuous silence; comic singers were hired to parody his noblest airs at the great houses; and impudent Horace Walpole had the audacity to say that he “had hired all the goddesses from farces and singers of roast-beef, from between the acts of both theatres, with a man with one note in his voice, and a girl with never a one; and so they sang and made brave hallelujahs.”

The new field into which Handel had entered inspired his genius to its greatest energy. His new works for the season of 1744 were the “Det-tingen Te Deum,” “Semele,” and “Joseph and his Brethren;” for the next year (he had again rented the Haymarket Theatre), “Hercules,” “Belshazzar,” and a revival of “Deborah.” All these works were produced in a style of then uncommon completeness, and the great expense he incurred, combined with the active hostility of the fashionable world, forced him to close his doors and suspend payment. From this time forward Handel gave concerts whenever he chose, and depended on the people, who so supported him by their gradually growing appreciation, that in two years he had paid off all his debts, and in ten years had accumulated a fortune of £10,000. The works produced during these latter years were “Judas Maccabæus,” 1747; “Alexander,” 1748; “Joshua,” 1748; “Susannah,” 1749; “Solomon,” 1749; “Theodora,” 1750; “Choice of Hercules,” 1751; “Jephthah,” 1752, closing with this a stupendous series of dramatic oratorios. While at work on the last, his eyes suffered an attack which finally resulted in blindness.

Like Milton in the case of “Paradise Lost,” Handel preferred one of his least popular oratorios, “Theodora.” It was a great favorite with him, and he used to say that the chorus, “He saw the lovely youth,” was finer than anything in the “Messiah.” The public were not of this opinion, and he was glad to give away tickets to any professors who applied for them. When the “Messiah” was again produced, two of these gentlemen who had neglected “Theodora” applied for admission. “Oh! your sarvant, meine Herren!” exclaimed the indignant composer. “You are tamnable dainty! You would not go to ‘Theodora’—dere was room enough to dance dere when dat was perform.” When Handel heard that an enthusiast had offered to make himself responsible for all the boxes the next time the despised oratorio should be given—”He is a fool,” said he; “the Jews will not come to it as to ‘Judas Maccabæus,’ because it is a Christian story; and the ladies will not come, because it is a virtuous one.”

Handel’s triumph was now about to culminate in a serene and acknowledged preeminence. The people had recognized his greatness, and the reaction at last conquered all classes. Publishers vied with each other in producing his works, and their performance was greeted with great audiences and enthusiastic applause. His last ten years were a peaceful and beautiful ending of a stormy career.

VIII.

Thought lingers pleasantly over this sunset period. Handel throughout life was so wedded to his art, that he cared nothing for the delights of woman’s love. His recreations were simple—rowing, walking, visiting his friends, and playing on the organ. He would sometimes try to play the people out at St. Paul’s Cathedral, and hold them indefinitely. He would resort at night to his favorite tavern, the “Queen’s Head,” where he would smoke and drink beer with his chosen friends. Here he would indulge in roaring conviviality and fun, and delight his friends with sparkling satire and pungent humor, of which he was a great master, helped by his amusing compound of English, Italian, and German. Often he would visit the picture galleries, of which he was passionately fond. His clumsy but noble figure could be seen almost any morning rolling through Charing Cross; and every one who met old Father Handel treated him with the deepest reverence.

The following graphic narrative, taken from the “Somerset House Gazette,” offers a vivid portraiture. Schoelcher, in his “Life of Handel,” says that “its author had a relative, Zachary Hardcastle, a retired merchant, who was intimately acquainted with all the most distinguished men of his time, artists, poets, musicians, and physicians.” This old gentleman, who lived at Paper Buildings, was accustomed to take his morning walk in the garden of Somerset House, where he happened to meet with another old man, Colley Cibber, and proposed to him to go and hear a competition which was to take place at midday for the post of organist to the Temple, and he invited him to breakfast, telling him at the same time that Dr. Pepusch and Dr. Arne were to be with him at nine o’clock. They go in; Pepusch arrives punctually at the stroke of nine; presently there is a knock, the door is opened, and Handel unexpectedly presents himself. Then follows the scene:

“Handel: ‘Vat! mein dear friend Hardgasdle—vat! you are merry py dimes! Vat! and Misder Golley Cibbers too! ay, and Togder Peepbush as veil! Vell, dat is gomigal. Veil, mein friendts, andt how vags the vorldt wid you, mein tdears? Bray, bray, do let me sit town a momend.’

“Pepusch took the great man’s hat, Colley Cibber took his stick, and my great-uncle wheeled round his reading-chair, which was somewhat about the dimensions of that in which our kings and queens are crowned; and then the great man sat him down.

“‘Vell, I thank you, gentlemen; now I am at mein ease vonce more. Upon mein vord, dat is a picture of a ham. It is very pold of me to gome to preak my fastd wid you uninvided; and I have brought along wid me a nodable abbetite; for the wader of old Fader Dems is it not a fine pracer of the stomach?’

“‘You do me great honor, Mr. Handel,’ said my great-uncle. ‘I take this early visit as a great kindness.’

“‘A delightful morning for the water,’ said Colley Cibber.

“‘Pray, did you come with oars or scullers, Mr. Handel?’ said Pepusch.

“‘Now, how gan you demand of me dat zilly question, you who are a musician and a man of science, Togder Peepbush? Vat gan it concern you whether I have one votdermans or two votd-ermans—whether I bull out mine burce for to pay von shilling or two? Diavolo! I gannot go here, or I gannot go dere, but some one shall send it to some newsbaber, as how Misder Chorge Vreder-ick Handel did go somedimes last week in a votderman’s wherry, to preak his fastd wid Misder Zac. Hardgasdle; but it shall be all the fault wid himself, if it shall be but in print, whether I was rowed by one votdermans or by two votdermans. So, Togder Peepbush, you will blease to excuse me from dat.’

“Poor Dr. Pepusch was for a moment disconcerted, but it was soon forgotten in the first dish of coffee.

“‘Well, gentlemen,’ said my great-uncle Zachary, looking at his tompion, ‘it is ten minutes past nine. Shall we wait more for Dr. Arne?”

“‘Let us give him another five minutes’ chance, Master Hardcastle,’ said Colley Cibber; ‘he is too great a genius to keep time.’

“‘Let us put it to the vote,’ said Dr. Pepusch, smiling. ‘Who holds up hands?’

“‘I will segond your motion wid all mine heardt,’ said Handel. ‘I will hold up mine feeble hands for mine oldt friendt Custos (Arne’s name was Augustine), for I know not who I wouldt waidt for, over andt above mine oldt rival, Master Dom (meaning Pepusch). Only by your bermission, I vill dake a snag of your ham, andt a slice of French roll, or a modicum of chicken; for to dell you the honest fagd, I am all pote famished, for I laid me down on mine billow in bed the lastd nightd widout mine supper, at the instance of mine physician, for which I am not altogeddere inglined to extend mine fastd no longer.’ Then, laughing: ‘Berhaps, Mister Golley Cibbers, you may like to pote this to the vote? But I shall not segond the motion, nor shall I holdt up mine hand, as I will, by bermission, embloy it some dime in a better office. So, if you blease, do me the kindness for to gut me a small slice of ham.’

“At this instant a hasty footstep was heard on the stairs, accompanied by the humming of an air, all as gay as the morning, which was beautiful and bright. It was the month of May.

“‘Bresto! be quick,’ said Handel; he knew it was Arne; ‘fifteen minutes of dime is butty well for an ad libitum.’

“‘Mr. Arne,’ said my great-uncle’s man.

“A chair was placed, and the social party commenced their déjeuner.

“‘Well, and how do you find yourself, my dear sir?’ inquired Arne, with friendly warmth.

“‘Why, by the mercy of Heaven, and the waders of Aix-la-Chapelle, andt the addentions of mine togders andt physicians, and oggulists, of lade years, under Providence, I am surbrizingly pedder—thank you kindly, Misder Custos. Andt you have also been doing well of lade, as I am bleased to hear. You see, sir,’ pointing to his plate, ‘you see, sir, dat I am in the way for to regruit mine flesh wid the good viands of Misder Zachary Hardgasdle.’

“‘So, sir, I presume you are come to witness the trial of skill at the old round church? I understand the amateurs expect a pretty sharp contest,’ said Arne.

“‘Gondest,’ echoed Handel, laying down his knife and fork. ‘Yes, no doubt; your amadeurs have a bassion for gondest. Not vot it vos in our remembrance. Hey, mine friendt? Ha, ha, ha!’

“‘No, sir, I am happy to say those days of envy and bickering, and party feeling, are gone and past. To be sure we had enough of such disgraceful warfare: it lasted too long.’

“‘Why, yes; it tid last too long, it bereft me of mine poor limbs: it tid bereave of that vot is the most blessed gift of Him vot made us, andt not wee ourselves. And for vot? Vy, for nod-ing in the vorldt pode the bleasure and bastime of them who, having no widt, nor no want, set at loggerheads such men as live by their widts, to worry and destroy one andt anodere as wild beasts in the Golloseum in the dimes of the Romans.’

“Poor Dr. Pepusch during this conversation, as my great-uncle observed, was sitting on thorns; he was in the confederacy professionally only.

“‘I hope, sir,’ observed the doctor, ‘you do not include me among those who did injustice to your talents?’

“‘Nod at all, nod at all, God forbid! I am a great admirer of the airs of the ‘Peggar’s Obéra,’ andt every professional gendtleman must do his best for to live.’

“This mild return, couched under an apparent compliment, was well received; but Handel, who had a talent for sarcastic drolling, added:

“‘Pute why blay the Peggar yourself, togder, andt adapt oldt pallad humsdrum, ven, as a man of science, you could gombose original airs of your own? Here is mine friendt, Custos Arne, who has made a road for himself, for to drive along his own genius to the demple of fame.’ Then, turning to our illustrious Arne, he continued, ‘Min friendt Custos, you and I must meed togeder some dimes before it is long, and hold a têde-à-têde of old days vat is gone; ha, ha! Oh! it is gomigal now dat id is all gone by. Custos, to nod you remember as it was almost only of yesterday dat she-devil Guzzoni, andt dat other brecious taugh-ter of iniquity, Pelzebub’s spoiled child, the bretty-f aced Faustina? Oh! the mad rage vot I have to answer for, vot with one and the oder of these fine latdies’ airs andt graces. Again, to you nod remember dat ubstardt buppy Senesino, and the goxgomb Farinelli? Next, again, mine some-dimes nodtable rival Bononcini, and old Borbora? Ha, ha, ha! all at war wid me, andt all at war wid themselves. Such a gonfusion of rivalshibs, andt double-facedness, andt hybocrisy, and malice, vot would make a gomigal subject for a boem in rhymes, or a biece for the stage, as I hopes to be saved.'”

IX.

We now turn from the man to his music. In his daily life with the world we get a spectacle of a quick, passionate temper, incased in a great burly frame, and raging into whirlwinds of excitement at small provocation; a gourmand devoted to the pleasure of the table, sometimes indeed gratifying his appetite in no seemly fashion, resembling his friend Dr. Samuel Johnson in many notable ways. Handel as a man was of the earth, earthy, in the extreme, and marked by many whimsical and disagreeable faults. But in his art we recognize a genius so colossal, massive, and self-poised as to raise admiration to its superlative of awe. When Handel had disencumbered himself of tradition, convention, the trappings of time and circumstance, he attained a place in musical creation, solitary and unique. His genius found expression in forms large and austere, disdaining the luxuriant and trivial. He embodied the spirit of Protestantism in music; and a recognition of this fact is probably the key of the admiration felt for him by the Anglo-Saxon races.

Handel possessed an inexhaustible fund of melody of the noblest order; an almost unequaled command of musical expression; perfect power over all the resources of his science; the faculty of wielding huge masses of tone with perfect ease and felicity; and he was without rival in the sublimity of ideas. The problem which he so successfully solved in the oratorio was that of giving such dramatic force to the music, in which he clothed the sacred texts, as to be able to dispense with all scenic and stage effects. One of the finest operatic composers of the time, the rival of Bach as an instrumental composer, and performer on the harpsichord or organ, the unanimous verdict of the musical world is that no one has ever equaled him in completeness, range of effect, elevation and variety of conception, and sublimity in the treatment of sacred music. We can readily appreciate Handel’s own words when describing his own sensations in writing the “Messiah:” “I did think I did see all heaven before me, and the great God himself.”

The great man died on Good Friday night, 1759, aged seventy-five years. He had often wished “he might breathe his last on Good Friday, in hope,” he said, “of meeting his good God, his sweet Lord and Saviour, on the day of his resurrection.” The old blind musician had his wish.

1891.

Featured: The Chandos Portrait of Georg Friedrich Händel, by unknown; painted ca. 1720.