I.

It is curious to note how often art-controversy has become edged with a bitterness rivaling even the gall and venom of religious dispute. Scholars have not yet forgotten the fiery war of words which raged between Richard Bentley and his opponents concerning the authenticity of the “Epistles of Phalaris,” nor how literary Germany was divided into two hostile camps by Wolf’s attack on the personality of Homer. It is no less fresh in the minds of critics how that modern Jupiter, Lessing, waged a long and bitter battle with the Titans of the French classical drama, and finally crushed them with the thunderbolt of the “Dramaturgie;” nor what acrimony sharpened the discussion between the rival theorists in music, Gluck and Piccini, at Paris. All of the intensity of these art-campaigns, and many of the conditions of the last, enter into the contest between Richard Wagner and the Italianissimi of the present day.

The exact points at issue were for a long time so befogged by the smoke of the battle that many of the large class who are musically interested, but never had an opportunity to study the question, will find an advantage in a clear and comprehensive sketch of the facts and principles involved. Until recently, there were still many people who thought of Wagner as a youthful and eccentric enthusiast, all afire with misdirected genius, a mere carpet-knight on the sublime battle-field of art, a beginner just sowing his wild-oats in works like “Lohengrin,” “Tristan and Iseult,” or the “Rheingold.” It is a revelation full of suggestive value for these to realize that he is a musical thinker, ripe with sixty years of labor and experience; that he represents the rarest and choicest fruits of modern culture, not only as musician, but as poet and philosopher; that he is one of the few examples in the history of the art where massive scholarship and the power of subtile analysis have been united, in a preeminent degree, with great creative genius. Preliminary to a study of what Wagner and his disciples entitle the “Artwork of the Future,” let us take a swift survey of music as a medium of expression for the beautiful, and some of the forms which it has assumed.

This Ariel of the fine arts sends its messages to the human soul by virtue of a fourfold capacity: Firstly, the imitation of the voices of Nature, such as the winds, the waves, and the cries of animals; secondly, its potential delight as melody, modulation, rhythm, harmony—in other words, its simple worth as a “thing of beauty,” without regard to cause or consequence; thirdly, its force of boundless suggestion; fourthly, that affinity for union with the more definite and exact forms of the imagination (poetry), by which the intellectual context of the latter is raised to a far higher power of grace, beauty, passion, sweetness, without losing individuality of outline—like, indeed, the hazy aureole which painters set on the brow of the man Jesus, to fix the seal of the ultimate Divinity. Though several or all of these may be united in the same composition, each musical work may be characterized in the main as descriptive, sensuous, suggestive, or dramatic, according as either element contributes most largely to its purpose. Simple melody or harmony appeals mostly to the sensuous love of sweet sounds. The symphony does this in an enlarged and complicated sense, but is still more marked by the marvelous suggestive energy with which it unlocks all the secret raptures of fancy, floods the border-lands of thought with a glory not to be found on sea or land, and paints ravishing pictures, that come and go like dreams, with colors drawn from the “twelve-tinted tone-spectrum.”

Shelley describes this peculiar influence of music in his “Prometheus Unbound,” with exquisite beauty and truth:

"My soul is an enchanted boat,

Which, like a sleeping swan, doth float

Upon the silver waves of thy sweet singing;

And thine doth like an angel sit

Beside the helm conducting it,

While all the waves with melody are ringing.

It seems to float ever, forever,

Upon that many-winding river,

Between mountains, woods, abysses,

A paradise of wildernesses."As the symphony best expresses the suggestive potency in music, the operatic form incarnates its capacity of definite thought, and the expression of that thought. The term “lyric,” as applied to the genuine operatic conception, is a misnomer. Under the accepted operatic form, however, it has relative truth, as the main musical purpose of opera seems, hitherto, to have been less to furnish expression for exalted emotions and thoughts, or exquisite sentiments, than to grant the vocal virtuoso opportunity to display phenomenal qualities of voice and execution. But all opera, however it may stray from the fundamental idea, suggests this dramatic element in music, just as mere lyricism in the poetic art is the blossom from which is unfolded the full-blown perfection of the word-drama, the highest form of all poetry.

II.

That music, by and of itself, cannot express the intellectual element in the beautiful dream-images of art with precision, is a palpable truth. Yet, by its imperial dominion over the sphere of emotion and sentiment, the connection of the latter with complicated mental phenomena is made to bring into the domain of tone vague and shifting fancies and pictures. How much further music can be made to assimilate to the other arts in directness of mental suggestion, by wedding to it the noblest forms of poetry, and making each the complement of the other, is the knotty problem which underlies the great art-controversy about which this article concerns itself. On the one side we have the claim that music is the all-sufficient law unto itself; that its appeal to sympathy is through the intrinsic sweetness of harmony and tune, and the intellect must be satisfied with what it may accidentally glean in this harvest-field; that, in the rapture experienced in the sensuous apperception of its beauty, lies the highest phase of art-sensibility. Therefore, concludes the syllogism, it matters nothing as to the character of the libretto or poem to whose words the music is arranged, so long as the dramatic framework suffices as a support for the flowery festoons of song, which drape its ugliness and beguile attention by the fascinations of bloom and grace. On the other hand, the apostles of the new musical philosophy insist that art is something more than a vehicle for the mere sense of the beautiful, an exquisite provocation wherewith to startle the sense of a selfish, epicurean pleasure; that its highest function—to follow the idea of the Greek Plato, and the greatest of his modern disciples, Schopenhauer—is to serve as the incarnation of the true and the good; and, even as Goethe makes the Earth-Spirit sing in “Faust”—

"'Tis thus over at the loom of Time I ply,

And weave for God the garment thou seest him by"—so the highest art is that which best embodies the immortal thought of the universe as reflected in the mirror of man’s consciousness; that music, as speaking the most spiritual language of any of the art-family, is burdened with the most pressing responsibility as the interpreter between the finite and the infinite; that all its forms must be measured by the earnestness and success with which they teach and suggest what is best in aspiration and truest in thought; that music, when wedded to the highest form of poetry (the drama), produces the consummate art-result, and sacrifices to some extent its power of suggestion, only to acquire a greater glory and influence, that of investing definite intellectual images with spiritual raiment, through which they shine on the supreme altitudes of ideal thought; that to make this marriage perfect as an art-form and fruitful in result, the two partners must come as equals, neither one the drudge of the other; that in this organic fusion music and poetry contribute, each its best, to emancipate art from its thralldom to that which is merely trivial, commonplace, and accidental, and make it a revelation of all that is most exalted in thought, sentiment, and purpose. Such is the aesthetic theory of Richard Wagner’s art-work.

III.

It is suggestive to note that the earliest recognized function of music, before it had learned to enslave itself to mere sensuous enjoyment, was similar in spirit to that which its latest reformer demands for it in the art of the future. The glory of its birth then shone on its brow. It was the handmaid and minister of the religious instinct. The imagination became afire with the mystery of life and Nature, and burst into the flames and frenzies of rhythm. Poetry was born, but instantly sought the wings of music for a higher flight than the mere word would permit. Even the great epics of the “Iliad” and “Odyssey” were originally sung or chanted by the Ilomerido, and the same essential union seems to have been in some measure demanded afterward in the Greek drama, which, at its best, was always inspired with the religious sentiment. There is every reason to believe that the chorus of the drama ofÆschylus, Sophocles, and Euripides uttered their comments on the action of the play with such a prolongation and variety of pitch in the rhythmic intervals as to constitute a sustained and melodic recitative. Music at this time was an essential part of the drama. When the creative genius of Greece had set toward its ebb, they were divorced, and music was only set to lyric forms. Such remained the status of the art till, in the Italian Renaissance, modern opera was born in the reunion of music and the drama. Like the other arts, it assumed at the outset to be a mere revival of antique traditions. The great poets of Italy had then passed way, and it was left for music to fill the void.

The muse, Polyhymnia, soon emerged from the stage of childish stammering. Guittone di Arezzo taught her to fix her thoughts in indelible signs, and two centuries of training culminated in the inspired composers, Orlando di Lasso and Pales-trina. Of the gradual degradation of the operatic art as its forms became more elaborate and fixed; of the arbitrary transfer of absolute musical forms like the aria, duet, finale, etc., into the action of the opera without regard to poetic propriety; of the growing tendency to treat the human voice like any other instrument, merely to show its resources as an organ; of the final utter bondage of the poet to the musician, till opera became little more than a congeries of musico-gymnastic forms, wherein the vocal soloists could display their art, it needs not to speak at length, for some of these vices have not yet disappeared. In the language of Dante’s guide through the Inferno, at one stage of their wanderings, when the sights were peculiarly mournful and desolate—

"Non raggioniam da lor, ma guarda e passa."The loss of all poetic verity and earnestness in opera furnished the great composer Gluck with the motive of the bitter and protracted contest which he waged with varying success throughout Europe, though principally in Paris. Gluck boldly affirmed, and carried out the principle in his compositions, that the task of dramatic music was to accompany the different phases of emotion in the text, and give them their highest effect of spiritual intensity. The singer must be the mouthpiece of the poet, and must take extreme care in giving the full poetical burden of the song. Thus, the declamatory music became of great importance, and Gluck’s recitative reached an unequaled degree of perfection.

The critics of Gluck’s time hurled at him the same charges which are familiar to us now as coming from the mouths and pens of the enemies of Wagner’s music. Yet Gluck, however conscious of the ideal unity between music and poetry, never thought of bringing this about by a sacrifice of any of the forms of his own peculiar art. His influence, however, was very great, and the traditions of the great maestro’s art have been kept alive in the works of his no less great disciples, Méhul, Cherubini, Spontini, and Meyerbeer.

Two other attempts to ingraft new and vital power on the rigid and trivial sentimentality of the Italian forms of opera were those of Rossini and Weber. The former was gifted with the greatest affluence of pure melodiousness ever given to a composer. But even his sparkling originality and freshness did little more than reproduce the old forms under a more attractive guise. Weber, on the other hand, stood in the van of a movement which had its fountain-head in the strong romantic and national feeling, pervading the whole of society and literature. There was a general revival of mediaeval and popular poetry, with its balmy odor of the woods, and fields, and streams. Weber’s melody was the direct offspring of the tunefulness of the German Volkslied, and so it expressed, with wonderful freshness and beauty, all the range of passion and sentiment within the limits of this pure and simple language. But the boundaries were far too narrow to build upon them the ultimate union of music and poetry, which should express the perfect harmony of the two arts. While it is true that all of the great German composers protested, by their works, against the spirit and character of the Italian school of music, Wagner claims that the first abrupt and strongly-defined departure toward a radical reform in art is found in Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony with chorus. Speaking of this remarkable leap from instrumental to vocal music in a professedly symphonic composition, Wagner, in his “Essay on Beethoven,” says: “We declare that the work of art, which was formed and quickened entirely by that deed, must present the most perfect artistic form, i.e., that form in which, as for the drama, so also and especially for music, every conventionality would be abolished.” Beethoven is asserted to have founded the new musical school, when he admitted, by his recourse to the vocal cantata in the greatest of his symphonic works, that he no longer recognized absolute music as sufficient unto itself.

In Bach and Handel, the great masters of fugue and counterpoint; in Rossini, Mozart, and Weber, the consummate creators of melody—then, according to this view, we only recognize thinkers in the realm of pure music. In Beethoven, the greatest of them all, was laid the basis of the new epoch of tone-poetry. In the immortal songs of Schubert, Schumann, Mendelssohn, Liszt, and Franz, and the symphonies of the first four, the vitality of the reformatory idea is richly illustrated. In the music-drama of Wagner, it is claimed by his disciples, is found the full flower and development of the art-work.

William Richard Wagner, the formal projector of the great changes whose details are yet to be sketched, was born at Leipsic in 1813. As a child he displayed no very marked artistic tastes, though his ear and memory for music were quite remarkable. When admitted to the Kreuzschule of Dresden, the young student, however, distinguished himself by his very great talent for literary composition and the classical languages. To this early culture, perhaps, we are indebted for the great poetic power which has enabled him to compose the remarkable libretti which have furnished the basis of his music. His first creative attempt was a blood-thirsty drama, where forty-two characters are killed, and the few survivors are haunted by the ghosts. Young Wagner soon devoted himself to the study of music, and, in 1833, became a pupil of Theodor Weinlig, a distinguished teacher of harmony and counterpoint. His four years of study at this time were also years of activity in creative experiment, as he composed four operas.

His first opera of note was “Rienzi,” with which he went to Paris in 1837. In spite of Meyerbeer’s efforts in its favor, this work was rejected, and laid aside for some years. Wagner supported himself by musical criticism and other literary work, and soon was in a position to offer another opera, “Der fliegende Hollander,” to the authorities of the Grand Opera-House. Again the directors refused the work, but were so charmed with the beauty of the libretto that they bought it to be reset to music. Until the year 1842, life was a trying struggle for the indomitable young musician. “Rienzi” was then produced at Dresden, so much to the delight of the King of Saxony that the composer was made royal Kapellmeister and leader of the orchestra. The production of “Der fliegende Hollander” quickly followed; next came “Tanhäuser” and “Lohengrin,” to be swiftly succeeded by the “Meistersinger von Nürnberg.” This period of our maestro’s musical activity also commenced to witness the development of his theories on the philosophy of his art, and some of his most remarkable critical writings were then given to the world.

Political troubles obliged Wagner to spend seven years of exile in Zurich; thence he went to London, where he remained till 1861 as conductor of the London Philharmonic Society. In 1861 the exile returned to his native country, and spent several years in Germany and Russia—there having arisen quite a furore for his music in the latter country. The enthusiasm awakened in the breast of King Louis of Bavaria by “Der fliegende Holländer” resulted in a summons to Wagner to settle at Munich, and with the glories of the Royal Opera-House in that city his name has since been principally connected. The culminating art-splendor of his life, however, was the production of his stupendous tetralogy, the “Ring der Nibelungen,” at the great opera-house at Baireuth, in the summer of the year 1876.

IV.

The first element to be noted in Wagner’s operatic forms is the energetic protest against the artificial and conventional in music. The utter want of dramatic symmetry and fitness in the operas we have been accustomed to hear could only be overlooked by the force of habit, and the tendency to submerge all else in the mere enjoyment of the music. The utter variance of music and poetry was to Wagner the stumbling-block which, first of all, must be removed. So he crushed at one stroke all the hard, arid forms which existed in the lyrical drama as it had been known. His opera, then, is no longer a congeries of separate musical numbers, like duets, arias, chorals, and finales, set in a flimsy web of formless recitative, without reference to dramatic economy. His great purpose is lofty dramatic truth, and to this end he sacrifices the whole framework of accepted musical forms, with the exception of the chorus, and this he remodels. The musical energy is concentrated in the dialogue as the main factor of the dramatic problem, and fashioned entirely according to the requirements of the action. The continuous flow of beautiful melody takes the place alike of the dry recitative and the set musical forms which characterize the accepted school of opera. As the dramatic motif demands, this “continuous melody” rises into the highest ecstasies of the lyrical fervor, or ebbs into a chant-like swell of subdued feeling, like the ocean after the rush of the storm. If Wagner has destroyed musical forms, he has also added a positive element. In place of the aria we have the logos. This is the musical expression of the principal passion underlying the action of the drama. Whenever, in the course of the development of the story, this passion comes into ascendency, the rich strains of the logos are heard anew, stilling all other sounds. Gounod has, in part, applied this principle in “Faust.” All opera-goers will remember the intense dramatic effect arising from the recurrence of the same exquisite lyric outburst from the lips of Marguerite.

The peculiar character of Wagner’s word-drama next arouses critical interest and attention. The composer is his own poet, and his creative genius shines no less here than in the world of tone. The musical energy flows entirely from the dramatic conditions, like the electrical current from the cups of the battery; and the rhythmical structure of the melos (tune) is simply the transfiguration of the poetical basis. The poetry, then, is all-important in the music-drama. Wagner has rejected the forms of blank verse and rhyme as utterly unsuited to the lofty purposes of music, and has gone to the metrical principle of all the Teutonic and Slavonic poetry. This rhythmic element of alliteration, or staffrhyme, we find magnificently illustrated in the Scandinavian Eddas, and even in our own Anglo-Saxon fragments of the days of Cædmon and Alcuin. By the use of this new form, verse and melody glide together in one exquisite rhythm, in which it seems impossible to separate the one from the other. The strong accents of the alliterating syllables supply the music with firmness, while the low-toned syllables give opportunity for the most varied nuances of declamation.

The first radical development of Wagner’s theories we see in “The Flying Dutchman.” In “Tanhhäser” and “Lohengrin” they find full sway. The utter revolt of his mind from the trivial and commonplace sentimentalities of Italian opera led him to believe that the most heroic and lofty motives alone should furnish the dramatic foundation of opera. For a while he oscillated between history and legend, as best adapted to furnish his material. In his selection of the dream-land of myth and legend, we may detect another example of the profound and exigeant art-instincts which have ruled the whole of Wagner’s life. There could be no question as to the utter incongruity of any dramatic picture of ordinary events, or ordinary personages, finding expression in musical utterance. Genuine and profound art must always be consistent with itself, and what we recognize as general truth. Even characters set in the comparatively near hack-ground of history are too closely related to our own familiar surroundings of thought and mood to be regarded as artistically natural in the use of music as the organ of the every-day life of emotion and sentiment. But with the dim and heroic shapes that haunt the border-land of the supernatural, which we call legend, the case is far different. This is the drama of the demigods, living in a different atmosphere from our own, however akin to ours may be their passions and purposes. For these we are no longer compelled to regard the medium of music as a forced and untruthful expression, for do they not dwell in the magic lands of the imagination? All sense of dramatic inconsistency instantly vanishes, and the conditions of artistic illusion are perfect.

"'Tis distance lends enchantment to the view,

And clothes the mountains with their azure hue."Thus all of Wagner’s works, from “Der fliegende Hollander” to the “Ring der Nibelungen,” have been located in the world of myth, in obedience to a profound art-principle. The opera of “Tristan and Iseult,” first performed in 1865, announced Wagner’s absolute emancipation, both in the construction of music and poetry, from the time-honored and time-corrupted canons, and, aside from the last great work, it may be received as the most perfect representation of his school.

The third main feature in the Wagner music is the wonderful use of the orchestra as a factor in the solution of the art-problem. This is no longer a mere accompaniment to the singer, but translates the passion of the play into a grand symphony, running parallel and commingling with the vocal music. Wagner, as a great master of orchestration, has had few equals since Beethoven; and he uses his power with marked effect to heighten the dramatic intensity of the action, and at the same time to convey certain meanings which can only find vent in the vague and indistinct forms of pure music. The romantic conception of the mediæval love, the shudderings and raptures of Christian revelation, have certain phases that absolute music alone can express. The orchestra, then, becomes as much an integral part of the music-drama, in its actual current movement, as the chorus or the leading performers. Placed on the stage, yet out of sight, its strains might almost be fancied the sound of the sympathetic communion of good and evil spirits, with whose presence mystics formerly claimed man was constantly surrounded. Wagner’s use of the orchestra may be illustrated from the opera of “Lohengrin.”

The ideal background, from which the emotions of the human actors in the drama are reflected with supernatural light, is the conception of the “Holy Graal,” the mystic symbol of the Christian faith, and its descent from the skies, guarded by hosts of seraphim. This is the subject of the orchestral prelude, and never have the sweetnesses and terrors of the Christian ecstasy been more potently expressed. The prelude opens with long-drawn chords of the violins, in the highest octaves, in the most exquisite pianissimo. The inner eye of the spirit discerns in this the suggestion of shapeless white clouds, hardly discernible from the aerial blue of the sky. Suddenly the strings seem to sound from the farthest distance, in continued pianissimo, and the melody, the Graal-motive, takes shape. Gradually, to the fancy, a group of angels seem to reveal themselves, slowly descending from the heavenly heights, and bearing in their midst the Sangréal. The modulations throb through the air, augmenting in richness and sweetness, till the fortissimo of the full orchestra reveals the sacred mystery. With this climax of spiritual ecstasy the harmonious waves gradually recede and ebb away in dying sweetness, as the angels return to their heavenly abode. This orchestral movement recurs in the opera, according to the laws of dramatic fitness, and its melody is heard also in the logos of Lohengrin, the knight of the Graal, to express certain phases of his action. The immense power which music is thus made to have in dramatic effect can easily be fancied.

A fourth prominent characteristic of the Wagner music-drama is that, to develop its full splendor, there must be a cooperation of all the arts, painting, sculpture, and architecture, as well as poetry and music. Therefore, in realizing its effects, much importance rests in the visible beauties of action, as they may be expressed by the painting of scenery and the grouping of human figures. Well may such a grand conception be called the “Art-work of the Future.”

Wagner for a long time despaired of the visible execution of his ideas. At last the celebrated pianist Tausig suggested an appeal to the admirers of the new music throughout the world for means to carry out the composer’s great idea, viz., to perform the “Nibelungen” at a theatre to be erected for the purpose, and by a select company, in the manner of a national festival, and before an audience entirely removed from the atmosphere of vulgar theatrical shows. After many delays Wagner’s hopes were attained, and in the summer of 1876 a gathering of the principal celebrities of Europe was present to criticise the fully perfected fruit of the composer’s theories and genius. This festival was so recent, and its events have been the subject of such elaborate comment, that further description will be out of place here.

As a great musical poet, rather epic than dramatic in his powers, there can be no question as to Wagner’s rank. The performance of the “Nibelungenring,” covering “Rheingold,” “Die Walküren,” “Siegfried,” and “Götterdämmerung,” was one of the epochs of musical Germany. However deficient Wagner’s skill in writing for the human voice, the power and symmetry of his conceptions, and his genius in embodying them in massive operatic forms, are such as to storm even the prejudices of his opponents. The poet-musician rightfully claims that in his music-drama is found that wedding of two of the noblest of the arts, pregnantly suggested by Shakespeare:

"If Music and sweet Poetry both agree,

As they must needs, the sister and the brother;

One God is God of both, as poets feign."From Great German Composers, by George T. Ferris (1840-1932), published in 1891.

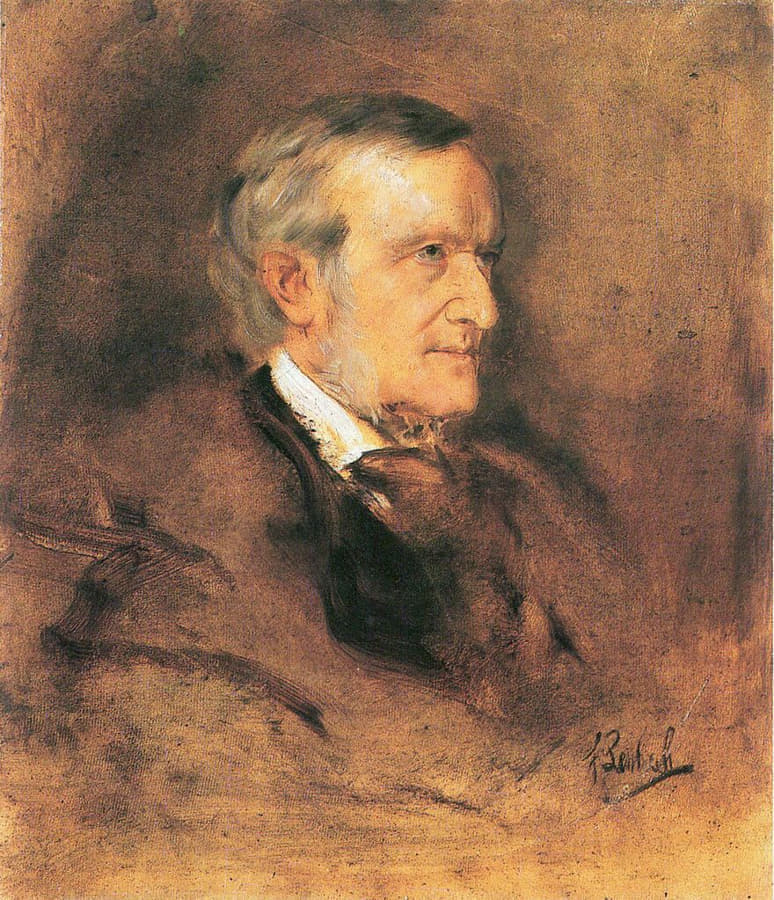

Featured: Portrait of Richard Wagner, by Franz von Lenbach; painted ca. 1882-1883.