The fact is little known outside a few specialists: a large part of the territory of today’s Azerbaijan corresponds to the borders of an ancient Christianized kingdom (probably as early as the 2nd century) known as Caucasian Albania (or Alwania). It disappeared in the 8th century, partly as a result of the Muslim conquest, and partly under pressure from its large Armenian neighbor.

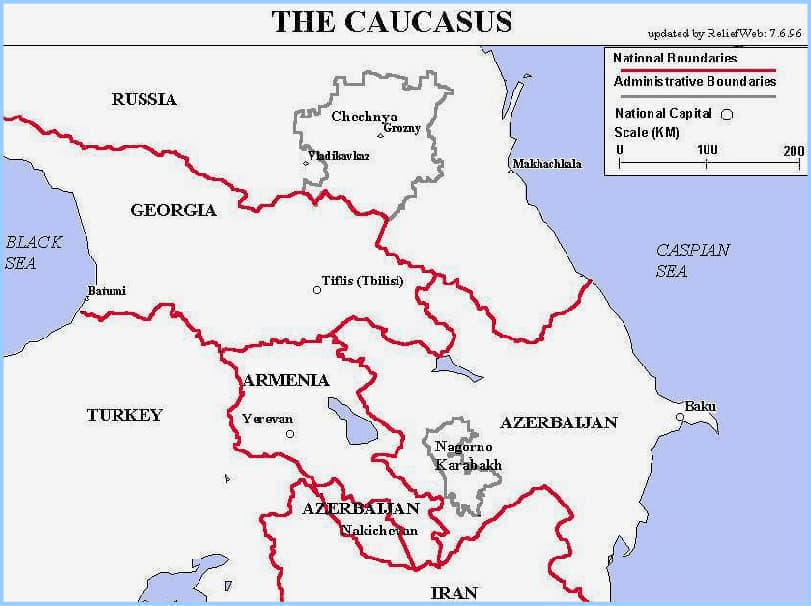

The coveted Karabakh (known as Artsakh) is one of the regions of this small kingdom attested by Greco-Latin and Armenian historiographical sources.

The discovery of an Albanian lectionary in 1975 at the Sinai monastery suggests the early Christianization of Albania, with links to Jerusalem, where Albanian communities financed the construction of several churches. The discovery was not widely publicized, but is well recounted by Bernard Outtier.

While this vanished Christianity is of no interest to the Christian or Catholic world, the Turks are particularly well-informed about the history of the Albanians of the Caucasus (the Baku school of history), and they are today exploiting this knowledge admirably to support their claim to Nagorno-Karabakh and assert their legitimacy over this territory, which they regard as a “proto-Azerbaijan.”

In February 2022, AZERTAC (Azerbaijan’s State Information Agency) posted an article by Mr. Rahman Mustafayev, Ambassador of the Republic of Azerbaijan to the Holy See: ” Les racines chrétiennes du Caucase. L’histoire de l’Église d’Azerbaïdjan [“The Christian Roots of the Caucasus. The history of the Church of Azerbaijan”]. In it, the author begins by tracing the main lines of the history of this small kingdom, which was Christianized very early on, a Church that, if not apostolic, was at least closely linked to the chain of the first disciples. And what he traces is consistent not only with what academic research has elaborated, but also with extant traditions, often oral.

The problem lies in the Azeri account of recent history: “At the beginning of the 19th century, following the Russo-Persian and Russo-Turkish wars, won by the Russian Empire, the process of settlement of Armenians from the Ottoman and Persian Empires began on the territory of the Karabakh, Erivan and Nakhchivan Khanates of the Russian Empire.”

All these territories were Armenian long before the Muslim occupation. It is not a question of “appropriating” Muslim territories, but of reappropriating the land from which they have been dispossessed, and this of course involves major human problems on both sides.

Assuming that the Armenians had to familiarize themselves with an Albanian architectural heritage and that they restored and renovated the monuments by introducing elements of Armenian architecture “that are not characteristic of Albanian architecture,” why is this scandalous? The two architectures, while not twins, are very similar. To claim that the Armenian epigraphy on medieval Albanian monuments constitutes the beginning of a process of “Armenization” is quite absurd, because the “Albanian” community has practically disappeared today. What remains is a “Udi” church, and a few speakers of the Udi language, which researchers admit is the heir to the Albanian language. In April 1836, the Tsarist government had abolished the Autocephalous Church of Albania, which was then subordinate to the Armenian Gregorian Church, according to the ambassador, in order to strengthen the position of the Armenian population and clergy in the Muslim territories of Transcaucasia. This may well be the case, and it was undoubtedly a pity for the little Albanian church. But it was also a political act. Since 2003, this small Albanian church has once again become autocephalous.

The extravagance of Azerbaijan’s accusations is astounding. If we are to believe their allegations, at the beginning of the 20th century, the Armenian Gregorian Church—with the authorization of the Russian Holy Synod—destroyed all traces of the archives of the Albanian Church, as well as the library of the Patriarchs of Albania in Gandjasar, which contained the most precious historical documents, as well as the originals of Albanian literature. The destruction (or concealment) of archives would thus have enabled Armenian historians and archaeologists to deny the autocephalous nature of the Albanian Church, the Albanian ownership of the Christian temples (?), monasteries and churches located on the territory of today’s Karabagh region, and to claim that they are the cultural heritage of the Armenian people and the property of the Armenian Church.

Today’s Albanian heritage obviously belongs to the Church of Armenia, not to the Muslim Azeris. To believe that the Azeri state has set up the great dome of secularism to give all churches their place in the country is to be naive or totally ignorant.

It is true that in the 8th century, Chalcedonian Albania was pressured by its large and prestigious neighbor to submit to Armenia’s anti-Chalcedonian choice. And after the conquest of the Caucasus by the armies of Islam, while Georgia emerged as a regional power and Armenia survived as a Christian power, Albania disappeared, at least politically. This is a matter for historical research. It is delicate because Albanian history is known mainly through Armenian historiography, and since history shows that spiritual and theological divisions were reflected in relations between states and kingdoms, religious theological conflicts were unfavorable to the small Albanian kingdom.

When the ambassador to the Holy See rejoices at “the liberation of Karabakh after 30 years of occupation,” and asserts that a new stage is beginning, so that “the Christian churches are returning to their masters, to the Albanian-Sudinian Christian community of Azerbaijan,” he is mocking us. The Albanian-Azerbaijani community is a mere pittance located in three cities in Azerbaijan (not even Baku). Are they naive enough to believe that their heritage will be restored to them under a Muslim regime? We are not. We have been searching the web in vain for images of the Albanian community so highly praised by the Azeris.

The tourist guides tell us: the Artsakh Ministry of Culture has restored the conventual buildings of the Gandjasar monastery, a major center for the copying of illuminated manuscripts in the Middle Ages, and has set up a Matenadaran (Yerevan’s BNF, albeit on a more modest scale) with the same functions: to exhibit the manuscripts created on Artsakh soil, some 100 of which are housed in the Matenadaran.

Vatican News has relayed Pope Francis’ call to protect the spiritual and architectural heritage of Nagorno-Karabakh. Here is what it says, written by Delphine Allaire:

“Nagorno-Karabakh’s millennia-old spiritual heritage makes it the cradle of Armenia. This pivotal region contains hundreds of churches, monasteries and tombstones dating from the 11th to the 19th century. Being mountainous, it was not evangelized at the same time as Armenia. However, Christianity in Nagorno-Karabakh is mainly because of the action of King Vatchagan the Pious who came to the throne in 484. He spread the cult of saintly relics, and the region owes him the construction of Karabakh’s oldest religious monument, the mausoleum of Grigoris, grandson of Saint Gregory the Illuminator and Catholicos of Albania in the Caucasus. Today, this monument is the Amaras monastery in eastern Artsakh. The history of Armenia and Caucasian Albania has been linked since the Christianization of the two countries in the early 4th century.”

This calls for a few comments.

Nagorno-Karabakh is an ancient region of Caucasian Albania, and thus the cradle of the Christian Albanians. But of these Albanians, only a tiny community remains: the Udi, whose language is that of the ancient Albanians, but whose writing has been lost. Thus, there is nothing wrong about this, and it is no falsification to claim it as the historical cradle of medieval Armenia, once the Albanian kingdom had disappeared.

At the beginning of January 2022, journalist Anastasia Lavrina (in the pay of the Azerbaijani government) carried out a curious investigation in Karabakh into “how the Christian churches of Karabakh were destroyed by Armenian separatists,” which was published on the website of the Journal musulmans en France a few days later. An impressive video shows the alleged exactions of the Armenians, as well as the testimony of an Orthodox priest from Baku on the freedom of worship enjoyed by the churches and the repair of this fabulous ancient heritage of which they are so proud. The images only show a priest commenting on all this in front of a small pile of old stones.

The same Journal des musulmans de France plagiarized Ambassador Mustafayev’s text to proclaim the liberation of Nagorno-Karabakh: “A new stage… in the history of Christian churches in Azerbaijan—a stage of restoration after destruction and historical falsifications, a stage of healing wounds, of rebirth to life in the name of peace and cooperation between all religions of Azerbaijan.”

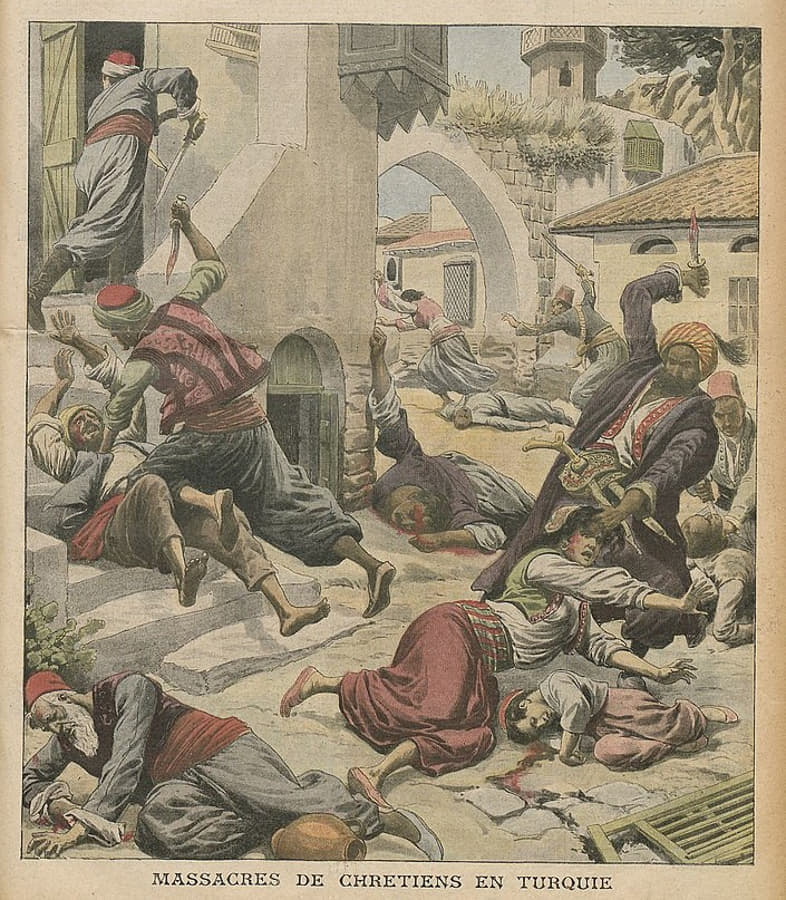

Who can believe that Azerbaijan will finance the restoration of Armenian heritage once it has emptied the country of all Armenians? We know the devastating rage of Islam. Mosques will cover the territory of Nagorno-Karabakh, erasing Christian memory and the religious roots of humanity, just as Turkey did in two bloody genocides.

But there is a lesson to be learned from all this propaganda, and it is an important one: Muslims have admitted the existence of a very old Albanian Christianity, old enough to confirm a very old, apostolic first evangelization, which Eastern tradition has maintained to the last.

Over and above this ancient history and the existence of a third Christianity in the Caucasus (totally ignored by the Caucasologists of our French media), most articles specializing in Caucasus affairs never cease to evoke “ethnic” or “racial” hatreds, and never mention “religious hatreds.” This ignores the Armenian genocide, which has been documented, even if not recognized by the nation historically responsible for it.

Almost all the articles available do not go beyond 1993, the supposed start of hostilities between Azeris and Armenians.

This silence is irresponsible, not to say guilty.

The question of Nagorno-Karabakh is an old one, whose seeds of death were sown by the British when they awarded Nagorno-Karabakh to Azerbaijan in 1919. Stalin merely ratified their decision.

At the end of 1918, Great Britain moved into the Caucasus. Through diplomacy, it made up for the few material resources it had in this “turbulent” region, as the experts put it. The cunning, deceitfulness, cynicism and well-understood self-interest of this England of the dying empire are well known. Her own, of course. The pretext invoked by the most imperialist circles in London to justify this presence in the Caucasus is that it was one of the roads into India. In reality, it is because of Baku’s oil. During British rule in 1919, Azerbaijan still had access to the oil that crossed Georgia to the port of Batumi (promised to Georgia, but occupied by the British). As for Armenia, it had been promised vast territories in Anatolia. But without the means to conquer or hold on to them. Meanwhile, hundreds of thousands of refugees were crammed into a tiny territory. Of what was then called “Turkish Armenia,” only one vilayet remained, that of Sivas, and only a handful of Armenians.

For Turkey, the Batumi treaties were nothing more than legal façades providing a pretext for invading the Caucasus. At the beginning of August 1918, Nuri Pacha demanded the annexation of Karabakh to Azerbaijan. The Armenian Republic refused. Once. Then a second time. The Turks then sent a Turkish-Azeri detachment against the capital, Shushi, which the Turks entered on October 8. The villages went into sedition, and the following month, taking advantage of their withdrawal, the Armenians regained control of the region.

In October 1918, Enver Pasha sent precise instructions to the Army of the Caucasus for the regions between the Transcaucasian republics and the line of retreat of the Turkish forces. Before withdrawing, the army was to arm the Kurdish and Turkish populations, leaving behind officers capable of organizing the region politically and militarily. The main objective was to prevent the repatriation of Armenians.

The commander-in-chief of British forces in the Caucasus, General William Montgomerie Thomson, was on the best of terms with the Azerbaijani government, which enabled Great Britain to obtain very large quantities of oil. On January 15, 1919, he authorized the appointment of an Azeri governor for the provinces of Karabakh (165,000 Armenians vs. 59,000 Azeris) and Zanguezur (101,000 Armenians vs. 120,000 Azeris).

In February 2019, the Azerbaijani administration entered Karabakh under British protection, while the Armenians held their fourth assembly in Shushi, which still refused to submit. Talks continued at the fifth assembly, held at the end of April with the participation of the Azeri governor and General Digby Shuttleworth, Thomson’s successor.

Armenian refusal persisted, and relations soured. On June 2, the Azeris attacked.

In August 1919, the Armenians accepted Azeri authority. Did they have any other choice?

On January 8, 1920, the Armenians signed an agreement with Major General George Forestier-Walker, commander of British forces in Batumi, for the establishment of an Armenian civil administration in Kars. When it arrived, escorted by the British, the Muslims refused to submit and, at the end of a large congress, proclaimed the provisional national government of the south-west Caucasus. General Thomson arrived in Kars and de facto recognized this government, while the Armenian administration turned back. With the Turks and Kurds making it impossible to repatriate Armenians to the west, the Armenians decided in January to attack Nakhichevan.

Thomson offered to help the Armenians take control of Kars and Nakhichevan, if they agreed to cede Karabakh and Zanguezur to the Azeris. Following an agreement in principle, Thomson occupied Kars on April 13 and dissolved the South-West Caucasus government. The British withdrew from Nakhichevan, leaving the administration to the Armenians. In July, the Muslims of Nakhichevan attacked the Armenians and forced them to evacuate the district.

When Colonel Alfred Rawlinson visited the Kars region in July, he found that, apart from the towns, the rest of the territory was held by the Kurds, from the Aras valley to Oltu and Ardahan.

What about the French? They knew, of course.

On December 10, 1918, Lieutenant-Colonel Pierre-Auguste Chardigny, commander of the French detachment in the Caucasus, sent a six-page letter to the Minister of War, in which he outlined the situation in the Caucasus and the proposed organization of the country.

He pointed out that “recent attempts at Russian colonization have produced a complete mixture of races and an incredible dispersion of populations,” and asked whether the organization of the Caucasus into four independent republics, “following the collapse of Russian power and the threat of Turkish invasion, is likely to provide the populations with the peace and prosperity to which they aspire?”

This is no rhetorical question. Here is the answer in extenso.

What is this organization?

“1. It is none other than the realization of our enemies’ plan, which can be summed up as follows:

a) Constitution of a large Muslim state in the Caucasus, uniting under Turkish protectorate the highlanders of the North Caucasus and the Tatars of Azerbaijan. This concept, of purely pan-Islamic origin, would have brought the Crescent to the edge of the Caspian Sea in the event of victory for the allied powers. The Republic of Armenia, born of necessity and reduced to infinite proportions, would have been short-lived, the disappearance of what remained of the Armenian people being the direct and fatal consequence of the Turkish plan.

b) Creation of an independent Georgia, under the protectorate of Germany, which would itself be responsible for exploiting the natural wealth of the most favored region in the Caucasus.

2. That none of the four new republics had sufficient resources to create an independent life for themselves, ensuring the country’s future development. Two of them, that of Azerbaijan and that of the Montagnards, do not even have an educated class large enough to ensure the direction of affairs, the mass of the people having so far remained in a state of profound ignorance.

In a note, the lieutenant-colonel pointed out that while in Georgia all Russian civil servants had been replaced by Georgians, in Azerbaijan, given the absolute lack of educated Muslims, Russian civil servants had been retained.

…Georgians and Tatars (Azerbaijanis), supported by German and Turkish bayonets, incorporated parts of the Armenian regions into their respective territories.“

Lieutenant-Colonel Chardigny concluded with a novel and intelligent proposal: that the Swiss model should be copied in the Caucasus and the region organized into “cantons.”

And he concluded, with a certain realism, that to save order in this country, a foreign master was needed, who could only be the Allies, acting in the name of Russia, until calm had been restored.

He concluded this intelligent letter with the fate of Russian Armenia (Caucasian Armenia) and that of Turkish Armenia, “a devastated and deserted country whose reconstitution would be a long-term task.”

The constitution of a large Muslim state in the Caucasus, uniting under Turkish protectorate the highlanders of the North Caucasus and the Tatars of Azerbaijan, is still on the agenda.

This is President Erdogan’s project.

The “fourth republic” of the North Caucasus did not last, but there is still Azerbaijan, a Turkish protectorate (or satellite) that takes the Crescent all the way to the Caspian.

The great Muslim state of the Caucasus, in a Turkish-speaking zone stretching from the Bosphorus to Central Asia: that is Turkey’s geopolitical vision.

Erdogan is moving forward, barely masked, with the same determination of his great predecessors, the gravediggers of the Christian Caucasus who did most of the work, with the duplicitous complicity of the Entente powers.

Today, France’s absurd support for Ukraine and the press’ aversion to Putin have foolishly deprived it of Russian gas. Today, it is turning to Azerbaijan (Baku) to obtain, in an unnatural alliance, what it could have continued to negotiate if it had chosen realism and common sense: to leave Zelenski to his destructive madness and demented plans; to turn away from a war decided and willed by NATO; to develop ties with Christian Russia prepared by three centuries of political, cultural and linguistic history.

Today, the gravediggers of the Christian Caucasus are still there, slyly preparing the ruin of the small Armenian state, an unfortunate landlocked state which today lies on the route of tomorrow’s oil pipelines.

And by the same token, irresponsibly organizing a future Muslim Caucasus.

Marion Duvauchel is a historian of religions and holds a PhD in philosophy. She has published widely, and has taught in various places, including France, Morocco, Qatar, and Cambodia. She is the founder of the Pteah Barang, in Cambodia.

Featured: Albanian Church in Kish, Shaki Rayon, Azerbaijan.