To present the genocide of the Armenians means first explaining the extinction of a multi-millennial civilization contemporary to the Romans and Parthians which almost disappeared from the Anatolian region at the dawn of the 20th century. While Western diplomats welcome the ongoing process of normalization between Armenia and Turkey, Armenians around the world commemorated on April 24 an unpunished genocide and their unburied dead.

In their masterful book, The Thirty-Year Genocide: Turkey’s Destruction of Its Christian Minorities, 1894-1924, Israeli historians Benny Morris and Dror Ze’evi estimate that the extermination of Ottoman Christians took place over thirty years. These were three historical sequences that were part of a single effort to wipe out the Christian presence in Anatolia. This process began with the proto-genocidal massacre of Ottoman Armenians from 1894 to 1896, followed by the genocide of 1915, and the deportation and annihilation of the remaining Christians (Greeks, Assyro-Chaldeans, Syriacs) during and after the Greek-Turkish war of 1919-1922, not to mention, in the Caucasus, the ethnic cleansing of the Armenians between 1918 and 1920 carried out by the Turkish-Azerian Islamic army.

Social Darwinism

Could the extermination of the Empire’s Christians have been avoided? Despite the adoption in 1876 of a liberal constitution crowning the era of reforms (Tanzimat) aimed at modernizing the Empire, the idea of a supra-confessional Ottoman citizenship remained a pious wish. The degrading notion of dhimmi, which instituted inequality between Christians and Muslims, remained a reality for millions of Greek, Armenian, Assyrian-Chaldean and Arab Christians. If in the countryside of eastern Anatolia, the Armenian peasantry, reduced to a state of serfdom, was at the mercy of the exactions of its Kurdish “protectors,” the fate of the Armenians of the Empire was relatively more enviable in the large cosmopolitan urban centers (Constantinople, Smyrna) and in Cilicia. The action of the Western missions favored the rise of an educated youth who had acquired the ideals of the Enlightenment.

The middle of the 19th century saw a national cultural revival (Zartonk), with a reform of the Armenian language and the emergence of an exceptional literature. The cultural and socio-economic gap between Armenians and Turks was all the more perceptible. Jealousy, frustration and even the anguish of disappearance haunted the Turks that arose with the defeats in Tripolitania and in the Balkans which, around 1912, accelerated the collapse of the Empire. The “sick man of Europe,” the Empire decomposed, while a new elite from the Balkans secretly organized itself and took power through a coup de force in 1908. The arrival of the Young Turks of the Committee of Union and Progress (CUP) was welcomed by a large number of Armenians, as the 1876 Constitution, which guaranteed equality between all the inhabitants of the Empire, was restored. Influenced by the positivist ideas of Auguste Comte, the Young Turks relied on the militants of the Armenian Revolutionary Federation with whom they had maintained close relations since their exile in Europe.

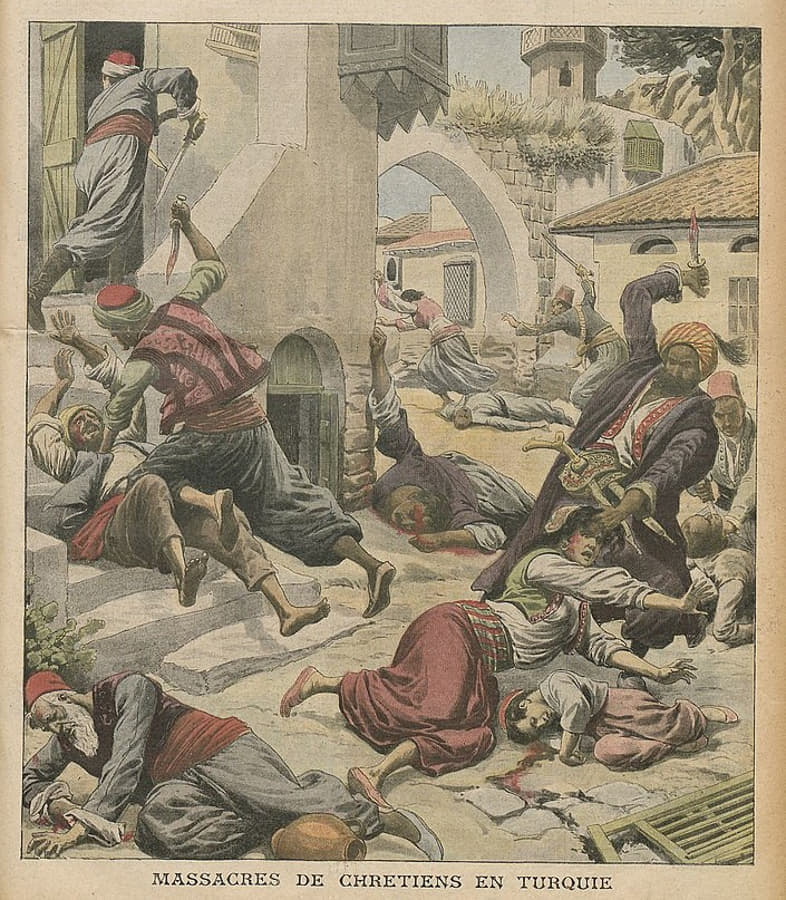

But the euphoria was short-lived. The Armenians of Adana, an opulent city in Cilicia, were massacred in 1909. The death toll was 30,000. The investigation was suppressed; the responsibility of the authorities was no longer in doubt. The ideal of a decentralized, multi-ethnic and multi-confessional Ottomanism was over. As the Young Turks retreated into the Balkans and North Africa, they came to consider Anatolia as the sanctuary of Turkishness. However, the Christian element was practically in the majority there. The Armenian elite was sufficiently seasoned to envisage autonomy, or rather an independent Armenia in the heart of the Empire. Social Darwinism explains the genocidal intention: if the “internal enemies” are not eliminated, the Turkish nation cannot exist within the borders of the Ottoman state.

The massacres of 1894-1896 had initiated a shift in the demographic balance of power reinforced by the influx of Muslim refugees (muhadjir) from the Balkans and the Caucasus, eager to fight the Christians. The Young Turks intended to ensure the transition from a multi-ethnic and multi-confessional state to an exclusively Muslim state where the Sunni Turkish element remained the basis of the emerging national identity.

The Last Act

The last act before the final solution was played out in 1913, with the firming of the power of the Young Turks who eliminated all opposition. On October 31, 1914, the Ottoman Empire joined Germany and Austria-Hungary in the war; and from then on, the thesis of the betrayal of Armenians fighting for Russia was used as a pretext to implement the Final Solution. Although they were atheists, the Young Turks used Islam and the Kurds to massacre the “infidel” Armenians. The Special Organization, the armed wing of the Deep State, recruited criminals released from prison.

In January 1915, Armenian conscripts of the Ottoman army were killed; and on April 24 the round-up of 3000 Armenian intellectuals, writers, politicians, doctors, lawyers, etc. in Constantinople destroyed the elite of this Christian minority. The Armenians of the eastern vilayets (counties) were exterminated on the spot, with the exception of the population of Van, who managed to resist and then to withdraw with the Russian army.

The “General Order for the deportation of all Armenians, without exception,” issued on June 21, 1915 by the Minister of the Interior Talaat, was addressed to all the governors of the vilayets. It no longer referred to threatened border areas, but to all regions of the Empire where Armenian subjects lived, up to the border with Bulgaria. Between May and September 1915, 306 convoys of deportees carried 1,040,000 Armenians from all over Anatolia. Parked in concentration camps, they died of thirst, hunger and disease. The survivors fled to the deserts of Syria.

In September 1915, a law on “abandoned property” of “temporarily” displaced persons legitimized the plundering of Armenian property.

In 1916, the second phase of the genocide began with the extermination of the Armenians who had not been deported from Anatolia, while Chechen irregulars were responsible for the heinous killing of the survivors (women, orphans, etc.) interned in the camps in Syria. A century later, Daech’s soldiers would repeat this barbarity at the exact scene of the crime earlier.

Turkey for the Turks

After having supported, in the years preceding the genocide, the demand for reforms in the eastern vilayets, in order to guarantee the Christian populations a minimum of security for their goods and persons, the Western powers were content to protest. On May 24, 1915, France, England and Russia, in a joint declaration, solemnly warned the Ottoman government of its full responsibility in “Turkey’s crime against humanity and civilization.” They promised the intervention of the secular arm of Justice. Strong words that remained a dead letter.

In 1923, 1.5 million deaths later, the international community cynically buried the Armenian question, sacrificed on the altar of realpolitik and the concern to spare Kemalist Turkey.

Thus, the slogan “Turkey for the Turks” became a reality. This was followed by an ethnocide, targeting the churches and monasteries of Anatolia. But the persecution did not stop there. Armenians, Greeks and Jews of Turkey who remained in the country after 1923 were subjected to a new spoliation by the iniquitous wealth tax of 1942.

In 1955, the pogroms in Istanbul, followed by the crises in Cyprus in 1963-1964 and 1974, put an end to the Greek presence in the city.

Successive military coups sustained an ultranationalism with Pan-Turkist overtones that led, for example, to the assassination in 2007 in Istanbul of the Turkish-Armenian journalist Hrant Dink. It is clear that, far from being a single memorial issue, the genocide remains a current one.

The other links in this chain are Cyprus, the Assyro-Chaldeans, the Kurds, the disregard for human rights. They are at the heart of the Turkish malaise. A country haunted by the ghosts of the past, sickened by its ultranationalism. A people that has still not found the path to inner peace and the beginning of a liberating request for forgiveness.

Read an interview with Tigrane Yégavian.

Tigrane Yégavian is a graduate of the Institut d’études politiques de Paris and the Institut des langues et civilisations orientales (INALCO), holds a Master’s degree in comparative politics with a specialization in the Muslim world, and is a doctoral candidate in contemporary history. An Arabist, he has spent a long time in Syria, Lebanon and Turkey. His career has led him to specialize in Eastern Christians and their diasporas. He is also a specialist in Portuguese and contemporary Portugal, on which he has written numerous articles. He is a member of the editorial board of the geopolitical journal Conflits. He is a contributor to the Revue des Deux Mondes, Etudes, Carto, Moyen-Orient, Politique Internationale, Le Monde Diplomatique, Sciences Humaines, France-Arménie and regularly appears on Télé Sud, RFI and TV5 Monde. This article appears courtesy of La Nef.

Featured: “The Massacre of Adana,” Le Petit Journal, May 2, 1909.