The article analyzes the Polish Question in the relationship between Russia and the West. The article considers the Polish Question as an instrument of the West’s ideological struggle against Russia. The article traces the main stages of Russian-Polish relations and concludes that since the Livonian War, Polish authors have been the main transmitters of negative myths about Russia as a barbaric, despotic and expansionist power. The article analyzes the role of the Polish factor in the formation of a negative image of Russia in the West during the partitions of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, and during the French Revolution and the Napoleonic Wars, when the first version of the fake Will of Peter the Great, created by the Polish General Michał Sokolnicki appears. The author analyzes the view of Russia through the prism of the Polish uprisings of 1830-1831 and 1863-1864 and concludes that European Polonophilism had the reverse side of hatred towards Russia. It also concludes that Russia’s suppression of the Polish uprising of 1830-1831 helped to cement its image, not just as an expansionist power, but as a state incompatible with the idea of freedom. It is also noted that despite the fact that after the uprising of 1863-1864 reforms were carried out in Poland, Russia remained the main enemy for new generations of patriotic Poles. The article analyzes the views on Russia of leading European politicians and public figures that were shaped under the influence of the Polish Question. The article also analyzes the racial concepts of Russian inferiority, which were originated by Polish authors, primarily Franciszek Henryk Duchiński, whose ideas had a great influence on the development of European anti-Russian thought.

Introduction

The relationship between Russia and Poland at different stages of historical development was not just complex, but often dramatic, marked by conflicts, Polish interventions, partitions of Poland, and uprisings. It was connected both with political, or, to put it in modern terms, geopolitical contradictions, and with no less important the religious factor, as the origins of the confrontation between Russia and the West are rooted in the split of the churches and the desire to induce Russia to accept the Union.

Beginning in the 14th century, Poland began to pursue an actively offensive policy in the Russian lands. At the same time, as the national researcher Oleg B. Nemensky rightly notes, as the Catholic country territorially closest to Russia, Poland historically was the main source of information about Russians for Western Europe. In 15th-16th centuries, Polish historians created a concept, according to which Russia has long belonged to Poland by right and for all eternity, since the campaigns to Kiev in the 11th century of Bolesław I the Brave and Bolesław II the Bold [Oleg Nemenski, “Rusofobiya kak ideologiya”—”Russophobia as an Ideology,” in Voprosy natsionalizma—Questions of nationalism, (1)2013, p. 13]. As a result, Poland already by the middle of the 16th century “had a full-fledged ideology of the conquest of Russia and the destruction of the “schisma,” i.e., Eastern Christianity” [Nemenski, 2013, p. 33].

From the Livonian War to the Partitions of Poland

During the years of the Livonian War (1558-1583), it was Polish publicists who came to be seen as the main experts on Russia. They became the main transmitters of negative myths about Russia as a barbaric, despotic and expansionist power.

As noted by historian Aleksandr I. Filiushkin, during the Livonian War, which Filiushkin calls the first confrontation between Russia and Europe, the idea of immanent hostility of “Asian” Russia to civilized Europe became one of the main aporias of European historical memory. It was the Polish nobility that played a key role in the formation of the myth of Asian and barbaric Muscovy, the antagonist of the Christian world, later picked up in other countries [A. Filyushkin, Kak Rossiya stala dlya Evropy Aziej? (How did Russia become Asia for Europe?), Moscow: Izobreteniye imperii. Yazyki i praktiki, 2011, p. 21]. The development of printing allowed publishing in large print runs of numerous works about Muscovy, which were distributed throughout Europe. According to O.B. Nemensky, the mass appearance of pamphlets that “exposed” the Russian people and its customs, the Moscow state and its rulers turned Muscovy in the minds of the West into “anti-Europe, a terrible and very dangerous country, combining all the known vices of the human race” [A. Filyushkin, Kak Rossiya stala dlya Evropy Aziej? (How did Russia become Asia for Europe?), Moscow: Izobreteniye imperii. Yazyki i praktiki, 2011, рр. 10-48., p. 34].

These were small texts written in simple style, mostly in German and Polish, which were the forerunners of the modern periodicals. They were modeled on the anti-Turkish pamphlets published in large numbers throughout the 16th century. As Belgian researcher Stefan Mund notes, it is not by chance that both were printed in the same printing houses [Review: A. Filyushkin, “Stéfane Mund, ORBIS RUSSIARUM: Genèse et development de la representation du monde “russe” en Occident à la Renaissance,” in Ab Imperio, (1)2004, p. 563]. And it is no coincidence that the Russians were subjected to pejorative characteristics attributed to the Turks, such as “bloody dogs,” “eternal cruel enemies,” and Russians were depicted on engravings in Turkish decorations [.F. Kudryavcev, “Neuznannaya civilizaciya. Zametki po povodu knigi Stefana Munda «Orbis Russiarum.» Genezis i razvitie predstavlenij o «Russkom mire» na Zapade v epohu Vozrozhdeniya” [“Unrecognized civilization. Notes on Stéfane Mund’s book Orbis Russiarum. Genesis and development of ideas about the ‘Russian world’ in the West in the Renaissance”], in Ancient Rus, 3(21)2005, p. 125].

The Vatican was concerned that victory in the Livonian War could lead to Muscovy’s domination in the Baltic and even beyond. In the future, the Vatican assumed that the Polish-Lithuanian kings would create an outer rampart of Europe, which would “stop at its foot all Muscovites and Tatars” [I. Noimann, Ispol’zovanie «Drugogo»: Obrazy Vostoka v formirovanii evropeiskih identichnostei [The Use of the “Other”: Images of the East in the Formation of European identities]. Moscow: New Publishing House, 2004, p. 110]. The long-prepared Brest Church Union in 1597 abolished legal Orthodoxy in Western Russia, and by the beginning of the 17th century Poles appeared in the Moscow Kremlin. And the conquest of Moscow immediately went under the slogan of “affirmation of Uniatism” [Oleg Nemenski, “Rusofobiya kak ideologiya”—”Russophobia as an Ideology,” in Voprosy natsionalizma—Questions of nationalism, (1)2013, p. 33].

For Europe, the Polish question was a trump card in the struggle with Russia and one of the main arguments for its accusations of expansionism and the desire to subjugate the whole world. These accusations intensified especially after the partitions of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth (1772, 1793, 1795). In spite of the fact that Russia, Prussia and Austria took part in them, it was Russia who became the main object of accusations of expansionism and the desire to enslave the unfortunate Poland.

It is no coincidence that it was the Polish author, General Michał Sokolnicki, who wrote the original text of the so-called The Will of Peter the Great. Even the American researcher Raymond McNally in 1958, and in 1967 the French researcher Simone Blanc came to the reasonable conclusion that the author of the original text of the document was Sokolnicki, who in 1797 wrote the document, “General Review of Russia” and offered it to the French Directory. It was a passionate appeal to France, which had forgotten its traditional policy of being an ally and protector of Poland, and which did not know that Poland and the whole of Europe was threatened by Russia [S. Blanc, “Histoire d’une phobie : le Testament de Pierre le Grand,” in Cahiers du monde russe et soviétique, 1(3-4)1968, p. 268]. The end of the text contained the “Plan of Peter I,” which, according to the author, was extracted from Russian archives, captured in Warsaw in 1794 [Blanc, 1968, p. 271]. The government of the Directory did not demand this document at that time, because the objectives were different.

However, Sokolnicki was remembered by Napoleon Bonaparte, who became First Consul and then Emperor in 1804, and who himself aspired to world domination, not mythical but real. In 1811, General Sokolnicki was summoned to Paris and took an active part in the secret preparations for war with Russia. It was Napoleon, having viewed and edited the text of Sokolnicki’s “Opinion on Russia,” ordered to include it in the book by Charles-Louis Lesur, Des progrès de la puissance russe: depuis son origine jusqu’au commencement du XIXe siècle (1812), which was to be published just before the beginning of the Russian campaign. The first version of Lesur’s book appeared in 1807, probably on the eve of the Peace of Tilsit. However, the work was actually published in October 1812. In any case, R. McNally has called this work one of the most influential in the history of Russophobia [R. McNally, “The Origins of Russophobia in France 1812-1830,” in American Slavic East and European Review, 3(17)1958, p. 173].

At the end of the chapter devoted to Peter I, a summary of the “Plan of Peter I” was given [Lesur, 1812, pp. 117-179]. As S. Blanc has noted, the summary of Lesur’s book differs only slightly from Sokolnicki’s text [Blanc, 1968, p. 268]. This leaves no doubt that we have before us one and the same “document,” which differed only by minor editing and very small changes.

The Polish Question in the 19th Century: Between the Congress of Vienna and the Polish Uprisings

The Polish Question became a stumbling block at the Congress of Vienna in 1814-1815, as Russia’s allies in the anti-Napoleonic coalition opposed the annexation of the entire territory of the Grand Duchy of Warsaw to Russia. Despite the fact that Russia granted the Grand Duchy of Poland within Russia wide autonomy and constitution, Europe perceived it solely as a propaganda measure to put to sleep the vigilance for further development of Russia’s expansionist plans [N.P. Tanshina, “Pol’skij vopros po zapiskam imperatora Nikolaya I i grafa Sh.-A. Pocco di Borgo” [“The Polish question according to the notes of Emperor Nicholas I and Count S.-A. Pozzo di Borgo”], in Novaya i noveyshaya istoriya, (2)2018, p. 15-26].

Following 1815, the Polish issue continued to be stirred up in Europe, and the ferment of minds was often the result of the hands of the Poles themselves, especially since European public opinion in liberalizing Europe was not in favor of powerful Russia. In particular, in 1829, under the influence of Polish agitation in Paris, L’ Histoire des legions polonaises en Italie sous le commandement du general Dombrovski, in two volumes, (History of the Polish Legions in Italy under the Command of General Dombrowski) was published, written by Leonard Chodzko; the Preface to the book included words about the Russian threat. (Jan Heinrich Dąbrowski (1755-1818), Polish military officer, division general of the Grand Army. After Napoleon’s abdication he returned to Poland).

The July Revolution of 1830 was the catalyst for the revolutionary movement in Europe. On November 29, 1830, an uprising began in Warsaw. The events in Poland went beyond the internal Russian problem and became the object of close attention and political discussions throughout Europe.

For the average Frenchman, supporting the uprising in Poland and favoring the development of the democratic idea in France were roughly the same thing. But King Louis-Philippe of Orleans was not at all inclined to interfere in the events in Poland, seeing it as an internal Russian affair. However, as in the case of the Russo-Turkish War of 1828-1829, government policy diverged from the mood of public opinion. The authorities, of course, were also Polonophile, but Louis-Philippe, wishing to be recognized as a full-fledged monarch who had no intention of fanning the fires of revolution and exporting it, refused to provide armed aid to Poland. Therefore, the Minister of Foreign Affairs, Horace François Bastien Sébastiani de La Portam declared France’s non-interference in the affairs of Poland.

Nevertheless, the public did not stop exerting serious pressure on the government, which, in the opinion of the French, was responsible for the current international situation [N.P. Tanshina, Politicheskaya bor’ba vo Francii po voprosam vneshnej politiki v gody Iyul’skoj monarhii (The Political Struggle in France on Foreign Policy Issues During the July Monarchy). Moscow: Prometheus, 2005, pp. 157-159]. In France, there was active propaganda in favor of Poland. Catholics played an important role in this case. For example, in the Catholic publication, L’Avenir, in December 1830, young Count Charles Montalembert (1810-1870) wrote that in the Polish uprising he saw the struggle of oppressed Catholics against Russian Orthodox-oppressors. The liberal Benjamin Constant and the Polish historian, geographer and social activist, Leonard Chodzko (1800-1871), made fiery speeches calling on all friends of freedom to support Poland. Volunteers were sent to Poland from Paris, Lyon, Strasbourg; Poles were helped by doctors; cultural figures organized charity lotteries in favor of the rebels [Charles Corbet, A l’ère des nationalismes. L’opinion française face à l’inconnue russe. 1799-1894 (1967), p. 161].

In the meantime, Field Marshal Ivan F. Paskevich was sent to Poland. He arrived with the troops on the night of June 13-14 and immediately began to prepare an offensive. At the beginning of August, Warsaw was encircled by Russian troops. The commander-in-chief delivered to the besieged an address by Nicholas I, who promised amnesty for the last time on condition of voluntary surrender of arms and submission to the imperial authority. The deputies of the Sejm rejected the proposal. On August 27 (September 7), 1831, after forty-eight hours of bloody fighting, Russian troops triumphantly entered Warsaw. On February 14/26, 1832, the “Organic Statute” was declared. Poland was deprived of the Constitution of 1815, the Sejm was dissolved, the Polish army was liquidated, and independent government was abolished. Poland became part of Russia with provinces instead of traditional voivodships. They retained only the right to some local liberties. According to the “Organic Statute,” Russian representatives were introduced into the Viceroy’s Council. A state of siege was declared in Warsaw. The leaders of the uprising and rebellious generals were exiled to Siberia and deprived of property, and their children were taken to be educated in the Russian army.

From the beginning of September 1831, the front pages of French newspapers were devoted to the events in Poland. When, finally, on September 15, France learned of Warsaw’s surrender, a riot broke out in Paris. In the streets there were shouts of “Long live the republic!” And Parisians broke the windows of the ministries, tried to get into the Palais Royal. For several days, there were anti-Russian popular demonstrations in the capital, which required the intervention of troops to subdue. Under the windows of the hotel building where the Russian embassy was located, shouts were heard: “Down with the Russians! Long live Poland! Revenge!” The windows of the embassy were broken with stones [Blanc, 1968, p. 220].

At times, Paris was covered by popular anger. In March 1831, news spread in the capital that the Russian army had entered Warsaw. Parisians marched on the Champs-Elysees with slogans “Death to the Russians!” The windows of the Russian Embassy were again broken; the police were barely able to protect it.

The French public reacted avidly to the events in Poland. For example, the famous poet, Auguste-Marseille Barthélemy, wrote: “Noble sister! Warsaw! She died for us! Died with weapons in her hands… Without hearing our cry of compassion… Do not talk any more about the glory of our barricades! You want to see the coming of the Russians: they will come.” Abbot Félicité Robert de La Mennais, in his article, “The Taking of Warsaw,” wrote: “Warsaw has fallen! The heroic Polish nation, abandoned by France, rejected by England, fell in the struggle with the barbarian hordes… Glorious nation, our brother in faith and in arms, when you fought for your life, we could only help you with compassion; and now that you are defeated, we can only mourn you. People of heroes, people of our love, rest in the grave where you have ended up because of the crime of some and the meanness of others. But hope is still alive, and the prophetic voice says: You will be reborn!” [A. Dumas (père), Mémoires, vols. 4-6 (1854), pp. 56-63].

Russia’s suppression of the uprising helped to consolidate its image, not just as an expansionist power, but as a state incompatible with the idea of freedom, which was especially used by liberals and radicals of all stripes. According to the American historian Martin Malia, these events produced a real metamorphosis in the perception of Russia and caused a real shock in Europe. Polish patriots were overnight not only suppressed, but also deprived of constitution and autonomy [Martin Malia, Russia under Western Eyes. From the Bronze Horseman to the Lenin Mausoleum (1999), p. 92]. As the researcher noted, for the first time, the system of autocracy was imposed, undoubtedly, on European territory. The West created a new image of Russia as a bastion of aggressive militant reaction [Malia (1999), p. 93].

Russia was reminded of the partitions of Poland and the entry of Russian troops into Paris, as well as the heroic resistance of the Poles. The words of French Foreign Minister Sebastiani, “Order reigns in Warsaw,” were circulated by the opposition and became the caption for a popular cartoon by Granville, which depicted a Cossack trampling the corpses of Poles. As the Swiss researcher Guy Mettan notes, “Nicholas I lost the laurels of the ‘liberator’ of Greece, which had long challenged other powers, and consolidated his reputation as an Asian despot” [Guy Mettan, Zapad—Rossiya: tysyacheletnyaya vojna. Istoriya rusofobii ot Karla Velikogo do ukrainskogo krizisa [The West—Russia: The Thousand-Year War. History of Russophobia from Charlemagne to the Ukrainian Crisis] (2016), p. 249].

The personification of the changes that occurred to Russia was Prince Adam Czartoryski, formerly a friend and minister of Emperor Alexander, now opposed to Nicholas as head of the Provisional Government in Warsaw.

According to Martin Malia, Europeans suddenly realized that “after France, Poland is the most heroic nation in Europe.” With the growth of the liberal movement in Europe, after the July Revolution, Poland was perceived as the main bulwark of all progressive values of the time, and received an additional halo of glory as the most faithful of the great emperor’s allies. As Malia correctly noted, the more Poland seemed to be a martyr, the more Russia seemed to be an executioner [Malia, 1999, p. 93].

After the suppression of the uprising, its leaders and, in general, many Poles emigrated and settled in different countries, mainly in France and in Great Britain [21]. It was Poles in the following years who raised a powerful anti-Russian wave and shaped public opinion about Russia. And since the Livonian War, Poles were the main “experts on Russia” and the main source of information, and such information was very much in the soul of the Polonophile-minded European public (V.F. Ratch, Pol’skaya emigraciya do i vo vremya poslednego myatezha 1831-1863 [Polish emigration Before and During the Last Rebellion of 1831-1863] (1866), p. 15).

The French government was sufficiently concerned about the presence of Poles in France. As early as November 1831, the government of Casimir Perrier, in an effort to remove the restless Polish element from the capital, issued a circular forbidding Poles from entering Paris. As a result, Polish emigrants were placed first in two large and then in several dozen small groups in provincial French towns where “Polish depots” were established, while only the wealthiest and generally moderate elements of the emigration remained in Paris.

In the years that followed, Poland was an important element in the internal political life of France, and the Polish Question did not stray far from the parliamentary agenda. Thus, at the January session of 1834, Narcisse-Achille de Salvandy, a prominent politician of those years, compared Russia’s actions in rebellious Poland to the policy of Genghis Khan and Tamerlane, but found Russia’s policy even more cruel. François Bignon, an opposition politician, solemnly declared that “the day when the Poles themselves will throw off their chains, or the day when other nations will free them from the bloody yoke pressing on them, will be the day when humanity will triumph over barbarism” [Corbet, 1967, p. 169].

At the same time, it cannot be said that European public opinion was unanimously against Russia, even after the July Revolution and the suppression of the Warsaw Uprising. Everything depended on the system of alliances on which European leaders relied within the framework of the “European concert” at any given moment. In particular, in France at that time, the legitimists, i.e., supporters of the overthrown legitimate Bourbon dynasty, were in favor of an alliance with Russia. Thus, the far-right newspaper Le Quotidienne supported Russia in the Polish issue, not without reason noting that the uprising in Warsaw was a consequence of the July Revolution [Corbet, 1967, p. 176].

In 1835, the Polish Question was once again on the pan-European agenda, and this was due to a speech made by Emperor Nicholas I, on October 5, 1835, in the Lazienkowski Palace in Warsaw. Speaking before a deputation of Polish townspeople, the emperor said: “If you obstinately cherish the dream of a separate, national, independent Poland and all these chimeras, you will only bring great misfortunes upon yourselves. At my command a citadel has been erected here, and I declare to you that at the slightest disturbance I will order to crush your city, I will destroy Warsaw and I will certainly not rebuild it again” [3, p. 215]. [3, с. 215]. This speech was perceived extremely negatively in the West. In the report of the Third Department for this year, it was reported: “It is not surprising that this speech neither the British nor the French liked. Having distorted it and given it a wrong meaning, they filled the newspapers with their reprimands, even rude swear words” [M.V. Sidorova, E.I. Shcherbakova, eds., Rocciya pod nadzorom. Otchety III otdeleniya 1827—1869 [Russia Under Surveillance. Reports of the Third Department, 1827-1869] (Moscow: Russian Cultural Foundation, 2006), pp. 129-131].

With this speech, the Emperor put a very powerful weapon in the hands of his detractors. Even if Nicholas’s character had been more accommodating, this speech would still have been the basis for a new wave of propaganda vilifying the Russians.

The famous journalist, politician, and Sorbonne professor Saint-Marc Girardin spoke very harshly of Emperor Nicholas, publishing a scathing article in his newspaper Le journal des débats, on October 10, 1835. Saint-Marc Girardin (Marc Girardin) (1801-1873) was a French politician, writer, journalist, literary critic and publisher, editor of Le Journal des Débats, and a member of the French Academy. A few months later, speaking in Parliament, on January 11, 1836, he declared that by “confiscating” Poland for itself, Russia had destroyed “one of the barriers protecting it” in Europe; and Girardin went on to trundle out the liberals’ favorite song that Russia and freedom are incompatible, and therefore “freedom is the best barrier against Russia.” And quite in the spirit of the already formed tradition, he frightened his fellow parliamentarians with the “Russian threat”: “Russia did not need a hundred years to reach almost to the door of Constantinople from Azov… It took her sixty years to be where she is now… Sixty more years will pass, and where will she be?” [Corbet, 1967, p. 178].

Many such pro-Polish statements were made. In particular, the already mentioned Count Montalembert until the 1860s consistently opposed Emperor Nicholas I and then Alexander II as far as “Holy Poland” was concerned, and from the Polish Question he turned to the Russian issue. On January 6, 1836, speaking in the House of Peers, he enumerated in detail the “atrocities” of Russia against the Polish people, in an attempt to show that the drama of the Poles was well within the general policy of Russia. The conquest of Poland was only a stage in the realization of a gigantic historical plan: the subjugation of the whole of Europe. Therefore, the Poles were defending not only their independence and their interests, but were defending “civilization against barbarism, the long and noble superiority of the West against the new invasion of the Tartars.” In doing so, Montalembert emphasized that Russia found “admirers and devotees everywhere,” but what did it promise Europe? “Darkness instead of light, military despotism instead of civil liberties, the shame of idolatrous schisma instead of the free beliefs of the West” [Corbet, 1967, pp. 179-180].

Every year, when the French Parliament debated the Address in response to the King’s Speech from the Throne, Montalembert used the opportunity to raise the Polish Question and renew his anti-Russian philippics. On November 17, 1840, on the wave of the Eastern crisis and anti-Russian sentiment, he said in the House of Peers: “We are all threatened by an ever-increasing danger, the predominance of Russia in Europe… Russia is already encircling Europe on all sides: its central border is only 200 leagues from the Rhine… From Bukovina to Kotor, the Slavic peoples of Austria profess her religion; she is awaited and called for” [Corbet, 1967, p. 181].

In England, these themes were developed by David Urquhart (1805-1877), whose name later became synonymous with Russophobia. Of course, Urquhart’s Russophobia was the reverse side of his Turkophilia, but Russian policy in Poland was also one of the main objects of his attacks. All the more so, because the documentary basis of the journal he published from November 1835 to 1837 in English and French (Portfolio, or Collection of State Documents … Illustrating the History of our Time) was the diplomatic documents provided to him by Polish emigrants. These were, first of all, the secret correspondence of Russian ambassadors, allegedly taken in 1831 from the chancery of Grand Duke Konstantin Pavlovich in Warsaw (in fact, most of the documents were forged by Urquhart) [K.V. Dushenko, “Pervye debaty o ‘rusofobii’ (Angliya, 1836–1841)”—”The First Debate about ‘Russophobia’: England, 1836-1841”], in Historical Expertise, 4(2021), p. 230].

Urquhart’s journals had great international resonance and were translated into foreign languages. In 1835, he published a pamphlet “England and Russia” (D.J. Urquhart, England, France, Russia & Turkey), in which he intimidated the reader with the “Russian threat,” emphasizing that for Poland “its space is void in the political map of Europe,” and the powers themselves allowed it, and the French government, moreover, did not help Poland [Urquhart, England & Russia (1835-1856), p. 1-2].

At the same time, in the eyes of Europeans, Poland was a bargaining chip in the defense of their own national interests. Therefore, when Russia was seen as an ally, the Polish Question was interpreted in a completely different way. Such metamorphoses, for example, happened with the famous politician and diplomat, Napoleon’s confessor, Abbé Dominique Dufour de Pradt (1759-1837). From the very beginning of the Restoration regime, he harshly criticized Russian policy, regularly actualizing the theme of the “Russian threat” and intimidating the French that Russia was “fifty leagues from Berlin and Vienna” [D.G.F. Pradt, Système permanent de l’Europe à l’egard de la Russie (1828), p. 6]. However, in 1836, amid the crisis of the French-English “cordial agreement,” Pradt bet on an alliance with Russia and published, Question de l’Orient Sous Les Rapports Généraux Et Particuliers, in which, among other things, he justified Russia’s policy in Poland, emphasizing that at the Congress of Vienna Russia’s demands on Poland were fair, and Poland thanks to Russia received a constitution [Pradt, 1828, pp. 122-123]. He even justified the suppression of the Polish uprising of 1830-1831 and the Warsaw speech of Emperor Nicholas, noting that any sovereign in his place would have done the same [Pradt, 1828, p. 134]. For the politically engaged Pradt, in this text, Russia is Poland’s natural protector, its real guardian angel. However, it should be understood that this was pure conjecture; for in general, the negative view of Russia through the Polish lens was dominant.

In 1839, Leonard Chodzko, mentioned above, a participant of the Polish uprising, published another version of the fake Will of Peter the Great. It was a bestseller, going through six editions from 1839 to 1847, and played a decisive role in popularizing, in European countries, the idea of the conquering intentions of Russian sovereigns [V.P. Kozlov, Tajny fal’sifikacii: Posobie dlya prepodavatelej i studentov vuzov (Secrets of Falsification: A Manual for Teachers and University Students), 1996, p. 81].

In the same year, Marquis de Custine traveled to Russia, writing the most famous book about the country, which to this day is perceived as a bible of Russophobes. Custine, being an outcast in the Parisian salons, had close ties, first of all, with the leaders of the Polish emigration and was a guest in the salon of the wife of Prince Adam Czartoryski. And in Russia, Custine came, according to one version, to advocate for his kind Polish friend Ignacy Gurowski, taking him with him (George Frost Kennan, The Marquis De Custine and His Russia in 1839, p. 24-25).

The most important source of information for Custine was one of the most famous Poles then living in Paris, the poet Adam Mickiewicz (1798-1855). After the suppression of the uprising, he lived in France as a political émigré, and in 1840, thanks to the persistent petition of the famous historian Jules Michelet, received a chair in Slavic languages and literature at the Collège de France. According to Michelet, “Mickiewicz had laid out the general features of Slavic life from above, and, descending into detail, cast deep, admirable glimmers on the true character of Russian government. He would have gone further, but they wouldn’t let him. His chair was nullified [Jules Michelet, Legendes démocratiques du Nord (1854), p. 36] (the authorities were dissatisfied with the preaching of Slavic messianism). This happened in 1844; and in 1849, the wave of Polish propaganda in five volumes was published as a collection of his “lectures”: Slavs [Corbet, 1967, pp. 168-169].

A new outbreak of anti-Russian sentiments occurred in 1846, after the suppression of the Krakow Uprising by Austrian troops, and again during the revolutions of 1848-1849, and especially after Russia suppressed the uprising in Hungary (at the request of the Austrian Emperor). But the apotheosis occurred during the Crimean War (1853-1856) [Nemenski, 2013, pp. 46-51].

On the eve of the war, Jules Michelet, who loved Poland with all his romantic heart and hated Russia just as passionately, wrote a series of articles entitled, Legendes démocratiques du Nord (The Democratic Legends of the North), in which he created a cult of unhappy Poland and the heroic Poles, and dehumanized the Russians, reducing them to the state of not just non-humans, but mollusks at the bottom of the sea. He called Russia’s policy towards Poland deceitful and Jesuitical, emphasizing that Empress Catherine “planned to drag Russia into a religious war, to make the Russian peasants think that it was a question of protecting their brothers in the Greek faith, who in Poland were being persecuted by people of the Latin faith. And this war, continued Michelet, “took on a character of appalling barbarity. Under the impetus of this atheist woman, who preached the crusade, populations and entire villages were tortured and burned alive in the name of tolerance” [11, с. 301]. According to Michelet, Catherine’s true goal was the destruction of Poland [Legendes démocratiques, pp. 53-54].

A similarly powerful anti-Russian wave swept over Europe during the Polish uprising of 1863-1864. Michelet worked hard this time too, publishing a series of articles entitled, “Martyr Poland,” while the equally illustrious Victor Hugo, also for the umpteenth time, unleashed invectives against Russia. Michelet called Poland, “the heart of the North.” Moreover, for him Poland is France itself: “La Pologne est une France avec tous nos anciens défauts, nos qualités” [Jules Michelet, La Pologne martyr: Russie—Danube, p. xv].

Concepts of Russian Racial Inferiority

It was Poles who stood at the origins of the concept of racial inferiority of Russians. Such ideas were first developed by the Polish historian and public figure, participant in the uprising of 1830-1831, Joachim Lelewel. In the form of a full-fledged theory, these ideas were formulated by the historian and ethnographer Franciszek Henryk Duchiński (1816-1893). After the suppression of the uprising of 1830-1831, he emigrated to France and was a professor of history at the Polish School in Paris. His main idea was that the Great Russians, or “Moskals,” do not belong to the Slavic and even to the Aryan tribe, but are a branch of the Turanian tribe, on par with the Mongols, and who only appropriated the name of Russians, which belongs, properly, only to the Little Russians and Belarusians, close to the Poles in their origin [F. Duhinski, “Osnovy istorii Pol’shi, inyh slavyanskih stran i Moskvy,” in, Russkij vopros v istorii politiki i mysli, antologiya, Pod red. A.Yu. Shutova and A.A. Shirinyanca (“Fundamentals of the History of Poland, other Slavic countries and Moscow,” in The Russian Question in the History of Politics and Thought, anthology, edited by A.Y. Shutov and A.A. Shirinyants], Moscow: Moscow University Press, 2013., p. 479].

Duchiński’s texts, which had no scientific basis, were aimed at justifying the necessity of creating a buffer between “Aryan” Europe and “Turanian” Moscow. This buffer was to be an independent Poland, including Ukraine-Rus, Belarus, Lithuania, the Baltic States, Smolensk and Veliky Novgorod.

Duchiński’s ideas were enthusiastically received by the Polish emigration, which dreamed of the restoration of a “Great Poland from sea to sea,” and his ideas also had a great influence on the Western European thought of the 19th century. In particular, Karl Marx was very interested in the concept of Duchiński and spoke in favor of it: “He claims that the real Muscovites, i.e., the inhabitants of the former Grand Duchy of Moscow, are mostly Mongols or Finns, etc., as well as the parts of Russia located further to the east and its southeastern part… I wish that Dukhinsky (thus in the text—NT) was right, and that at least this view would prevail among the Slavs” [letter dated June 24, 1865, in Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, Werke, (Berlin: Dietz Verlag, 1978), vol. 31, pp. 126–127].

Duchiński’s theory was enthusiastically accepted by French intellectuals and politicians—E. Renaud, Aimé Martin, K. Delamar and others [Shutova and Shirinyanca (2013), p. 43]. Thus, the historian, publicist and politician Henri Martin (1810-1883), author of Histoire de France (History of France) in nineteen volumes, characterized by an extremely hostile attitude to Russia, in one of his major works, La Russie et l’Europe (1866) (Russia and Europe) described the Russians as a barbaric people of non-European (Turanian) despotism, who had unjustly appropriated the history of Russia. He considered Duchiński’s concept as “excellent,” and explained the Russian craving for subjugation as follows: “Such a feeling arises in peoples who are at an extremely low stage of cultural development of nations, where an individual person is unable to control his fate and does not even express such a desire” [Shutova and Shirinyanca (2013), p. 382].

Despite the fact that after the uprising of 1863-1864, reforms were carried out in Poland, Russia remained the main enemy for newer generations of patriotic Poles, so that at the end of the 19th century, Józef Piłsudski (1867-1935) proclaimed the main goal of his life as the physical destruction of the Russian state with the subsequent restoration of a new Poland, dominating in Central and Eastern Europe on Russia’s ruins [Shutova and Shirinyanca (2013), p. 45]. In the article “Russia,” first published in 1895, he noted: “The Russian Tsar is the main enemy of the Polish working class. Tsarist autocracy—the main obstacle in our way, now and always” [Shutova and Shirinyanca (2013), p. 514].

Conclusion

As the current situation shows, these ideas did not pass away with Pilsudski—and Poles are still perceived in the West as the main experts on Russia. And, of course, the West willingly believes them, because Polish scary myths about Russia, ideas about Russian “Asianness” and Russians “stealing” history fit very well into the pan-European narrative of a barbaric, despotic and expansionist Russia. And Poles, of course, can speak only “the truth” about Russia, and the West willingly believes in this Polish “truth” and uses it in its ideological and geopolitical confrontation with Russia—without thinking much about the Poles themselves. Only now, Ukraine is the “martyr,” and Western love for Ukraine is the reverse side of hatred for Russia.

Natalia P. Tanshina, is Professor in the Department of General History at the Institute of Social Sciences of the Russian Academy of National Economy and Public Administration under the President of the Russian Federation, and is Professor at the Department of Modern and Contemporary History of Europe and America, Moscow State Pedagogical University, Moscow. This article appears courtesy of Nauka Obshestvo Oborona.

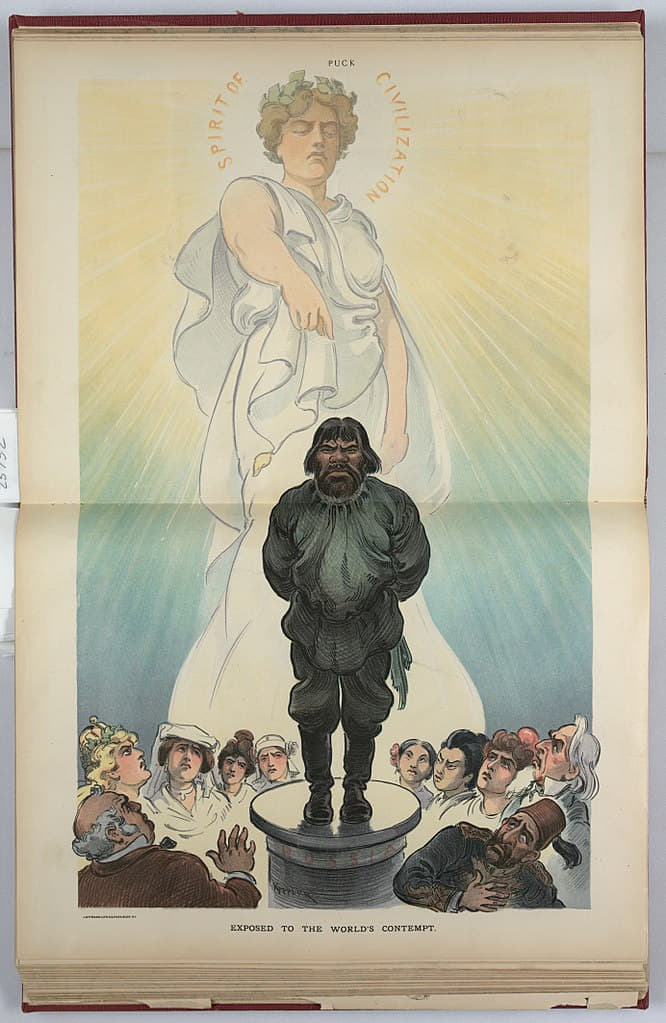

Featured: Exposed to the world’s contempt, illustration by Udo J. Keppler, Puck, June 17, 1903.