It is traditional in the doctrine of French law, of a state formed by eight centuries of monarchy, to begin the treatment of public powers from the theological justification of power itself. This is followed by the exposition of the theory of divine right and the distinction between “doctrine du droit divin surnaturel” and “doctrine du droit divin providential,” attributing the affirmation of the former to the Kings of France (Barthélemy – Duez) and particularly to Louis XIV and Louis XV, or Bossuet (Hauriou); while for the latter the attribution is concordant to de Maistre and de Bonald. The distinction between the two conceptions is set forth as follows by Hauriou:

“Theological doctrine had two successive forms in France: 1) The doctrine of supernatural divine right (Bossuet), which consists in maintaining that God Himself chooses rulers and invests them with their powers: this conception is compatible only with absolute monarchy; 2) The doctrine of divine providential law (de Maistre and de Bonald), according to which power, in its fundamental principle is part of the providential order of the world, but is at the disposal of the rulers through human means; this doctrine equally adequately allows for both the justification of minority power, exercised by an elite, and majority power, exercised by the majority of the people (vox populi vox Dei).”

Hauriou goes on to point out the advantages of this second theory: 1) to signify that the instinct of power is in human nature, and in that sense, pre-social; 2) to place the origin of power above both the social collectivity, the right of the rulers, and anyone: that is, to lead to no absolutism; it is most conducive to freedom; 3) coming from God, power is by nature oriented toward reason, justice and the common good.

Most importantly, as becomes evident from the systematic context of these considerations, it allows for reconnecting pouvoir de fait and pouvoir de droit, that is, for “opening” law to the changes of history. In a more specific sense, to ground constituent (human) power above the constitution itself. Barthélemy and Duez argue, likewise, that the doctrine of divine providential law is not necessarily aristocratic or monarchical, because any man or class can be chosen by Providence to execute its designs: thus it is not contrary to democracy. Both Barthélemy and Carré de Malberg regard the doctrine of divine providential right as already formulated by St. Thomas and followed by most Catholic theologians.

This conception, however, is not considered by all jurists to be an “antecedent” to modern democracy. Jellinek, in writing about modern democracy—and republics—traces them back to Reformation conceptions, particularly Calvinist. Otto von Gierke believes that it was “the Reformation that revived theocratic thought with new energy. Through all the differences in their conceptions, Luther, Melanchthon, Zwingli and Calvin agreed in insisting on the Christian function and thus the divine right of rulers. Indeed, since on the one hand they more or less decisively subject the dominion of the Church to the state and on the other hand they legitimize the existence of the state on the basis of the fulfillment of its religious duties, they give St. Paul’s principle omnis potestas a Deo a hitherto unknown scope.”

However, von Gierke does not neglect the doctrine of Second Scholasticism, and writes that the most ardent opponents of the Reformation, “particularly the Dominicans and the Jesuits wielded all their spiritual weapons in favor of a purely temporal construction of the State and the right of sovereignty” (also to support the thesis of potestas indirecta implying a limited subordination of the State to the Church).” Leaving out of account, however, the relations with the Church, they actually developed a doctrine of the state devoid of any dogmatic presuppositions, on purely philosophical foundations: This is true not only of the authentic monarchians of this group: Even the leading theorists of this tendency agree that the state union has its roots in natural law, that by virtue of this it is incumbent on the associated collectivity to have sovereignty over its members, and that all rights of the rulers come from the will of the collectivity to which natural law attributes the faculty and obligation to transmit its powers.”

Carl Schmitt argues: “According to the medieval conception, only God has a potestas constituens, as far as this can be spoken of—the phrase, “all power (or authority) comes from God” (“Non est enim potestas nisi a Deo,” Rom. 13:1) means the constituent power of God. The political literature of the Reformation era also adheres to this, especially the theory of the Calvinist monarcomacs,” and continues that with Sieyés’ doctrine of pouvoir constituant; it is the nation that is the subject of constituent power; despite the development of absolutism in the 17th century, the absolute prince is not yet defined as the subject of constituent power, but only because the idea of a free total decision, made by men, on the form and species of their political existence very slowly could develop into political action: The consequences of theological-Christian conceptions of God’s constituent power in the 18th century, despite the Enlightenment, were still too strong and vital.”

It remains to be seen to what extent the theory of pouvoir constituent—and by extension, of national sovereignty—is the result not only of the Enlightenment, the conceptions of Rousseau and the Jacobins, but of Christian political theology and more specifically, of the theory of divine “providential” law.

That Sieyés’s conception was the secularization of political theology, with the Almighty Nation in place of the Almighty God is clear; it is less so whether such a conception was tributary to the reflections of seventeenth-century philosophers—particularly Hobbes and Spinoza (and, later, Rousseau)—or to Catholic and Reformed theology, particularly of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, or to jurists who were theorists of natural law. Indeed, the connotations of such a conception, which serve to distinguish it, are, in addition to those indicated by Hauriou, others, present in the thought of the revolutionary abbot.

Sieyés argues that the “Nation exists before everything; it is the origin of everything: its will always conforms to the law; it is the law itself: Before it and above it there is only natural law” and continues, “In every part of it, the Constitution is not the work of the constituted power, but of the constituent power: No kind of delegated power can change anything about the conditions of its own delegation. It is in this sense and in no other that constitutional laws are fundamental. The former, those constitutive of legislative power, are founded by the national will before any Constitution. They form its first step.” He repeatedly insists on the concept of will, “which is outside all form,” and that “a Nation can neither alienate nor interdict to itself the faculty of will; and whatever its will may be, it cannot lose the right to change it should its interest demand it;” thus, “When even it is granted it, a Nation must not bury itself in the fetters of a positive form: It would be tantamount to risking the irrevocable loss of its freedom, for it would only take a single occasion favorable to tyranny, to bind the people, under the pretext of the Constitution, to a form that would prevent them from freely expressing their will, and thus freeing themselves from the shackles of despotism.” It is clear that in this way, the community’s “right” to give itself the institutional form it prefers without the morphopoietic will of the Nation being subject to any legal constraint is founded.

In effect, such a conception of Sieyés means that there is no right to the power of anyone by divine investiture, but only the potestas of the community to give itself the form it prefers: the shaping of the form, and thus the right and choice of who exercises power is left to human will and work. To some extent, it “updates” the thinking of Christian theology, and Thomist theology in particular, on tyranny, based on the principle that “tota respublica superior est rege.”

Similarly, in Sieyés, the human tendency to associate is natural: man is a political animal, as Christian theology has always repeated, so he is naturally inclined to associate the political instinct—of order and power—is therefore natural and, even, pre-social, as Hauriou argues. And theologians in various ways have argued both the character of natural law and the reasonableness of the aggregation of men in society; mostly explaining it by human weakness, man not having natural weapons such as fangs, claws and having to defend himself from beasts, as well as from other men; hence the need to constitute a common power and enforce the law. Not unlike the representations of the theologians is what Sieyés wrote: “There is, in truth, a great inequality of means among men. Nature creates them strong or weak; to some it grants intelligence, while to others it rejects it. It follows that there will be among them inequality of labor, inequality of results, inequality of consumption or enjoyment; but it does not follow that there can be inequality of rights,” whereby “the right of the weak over the strong is the same as that of the strong over the weak. When the strong succeeds in oppressing the weak, it produces an effect without producing an obligation. Far from imposing a new duty on the weak, it revives in them the natural and imperishable duty to resist the oppressor,” and “So a society founded on mutual utility is in harmony with the natural means offered to man to achieve his end; in this sense this union is a good, and not a sacrifice, and the social order becomes an extension, a complement of the natural order.” Association in society is reasonable because the welfare state does not tend to degrade, to demean men, but, on the contrary, to ennoble them, to perfect them.

Thus “society does not weaken, does not reduce the particular means which each individual brings to the association for his personal benefit; on the contrary, it increases them; it multiplies them, by developing moral and physical faculties; it increases them still through the fundamental concurrence of labor and public relief,” and, “Man, by entering society, does not therefore sacrifice a part of his freedom: even when there was no social bond, no one had the right to harm another.” And, “Far from limiting individual freedom, the welfare state amplifies and secures its enjoyment; it removes a multitude of obstacles and dangers to which it was exposed, when it was secured solely by private force, and entrusts it to the omnipotent control of the whole association. Thus, since in the social state man increases his moral and physical means, while at the same time removing himself from the restlessness that accompanies their use, it is not erroneous to say that freedom is completer and more absolute in the social order than it can be in the so-called state of nature.” Contrary to Rousseau’s assertion, therefore, the judgment on the welfare state is positive, as Christian theology has always maintained. There is nothing of the heartfelt beginning of the Contrat social: “Man was born free and is everywhere in chains,” nor of Rousseau’s explanation of the welfare state in the Discours sur l’origine de l’inégalité parmi les hommes, as a solution that favors the richest, who secure with public power their positions.

Bossuet explains the well-known passage from St. Paul’s Epistle to the Romans as follows: princes act as God’s ministers and His lieutenants on earth; their throne is not that of a man, but that of God Himself; the person of the king is sacred, even if he is not Christian like Cyrus , because he always represents the Divine majesty. Authority is in the image of God: the prince is the material image of (God’s) immortal authority. In the prince, man may die but authority never dies; the only principle that can ensure the stability of states is that every subject must respect the exercise of public powers and judgments. On the other hand, according to Bossuet only to the prince belongs the power to command legitimately and to him alone the exercise of coercion. If this were not so, the state (the community) would fall back into anarchy; from which it emerged precisely because it constituted (became) a people under a sovereign.

Indeed, as can be seen, the conception of the pouvoir constituant bears a close affinity with the conception of divine providential law with which it shares the main points of contact: That then the theory is itself, as mentioned, the secularization of Christian theology, with the Nation being given the connotations of God is even more evident: the absence of (legal) limits—the omnipotence of the will of the nation; its ability to “create” order, bestowing by the constitution on the one hand an order (a form) that “surpasses” chaos, and on the other hand the very capacity for political action (and existence); the resolution of the distinction/antithesis between being and ought-to-be.

But it is no less true that, in his defense of the “goodness” of the association of men, Sieyés took up what Christian theology has always maintained: in fact, already St. Augustine linked order, peace, and civitas, emphasizing the concord, which, in “temporal” things there was between the earthly city and the heavenly city. On the other hand, the conception of divine providential law was expounded in other respects, more articulated than those mentioned so far, by St. Robert Bellarmine. The latter, in also refuting the theses of the Anabaptists, adduces five proofs, three of them “logical” (deductive-rational) and two “historical.” Of particular interest is the distinction between authority (willed by God is therefore good in itself, being part of the order of creation) and those who exercise it, namely the ruler (who, as a human being is always subject to sin and error): “To what the Anabaptists say to the contrary, I affirm first of all that it is not true that kings and princes are generally evil: for we are not dealing here with a particular state, but with political power in general; and in this sense, Abraham was king and prince also.” He continues: “the examples of evil kings do not prove that political power is evil in itself; for bad people often make use of good things; but the examples of good kings prove that political power is good, because good people do not make use of bad things. Further, bad princes are often of more benefit than harm, as was the case with Saul, Solomon and others. Besides, it is even more useful for a state to have a bad prince than to have none; for where there is none, the state cannot preserve itself for long: Solomon himself said so (Prov. 11:14): “Where there is no governor, the people shall fall: but there is safety where there is much counsel.” Better a bad ruler than the anarchy of non-government.

On political power: “In this regard, however, some observations are to be made. The first is this: political power in general, i.e., not considered in its particular forms of monarchy, aristocracy or democracy, comes immediately from God alone, since it is a necessary consequence of the nature of man;” and originally resides in the multitude: “For since this power is of divine right, this right did not give power to any particular man; it therefore gave it to the whole multitude.” And, “natural law itself transfers political power from the multitude to one or more individuals. For the multitude cannot exercise this power itself, and therefore it is obliged to transfer it to one or a few individuals. Therefore, the power of princes, considered in general, is itself of natural and divine right, and mankind, even if all men agreed in this, could not establish the contrary, that is, that there were no princes and leaders.” However, “the particular forms of political regime are ‘de jure gentium‘ and not of natural law, since it is clear that it depends on the free will of the multitude to determine that it governs a king or some consuls or other magistrates; and, if there is a legitimate cause, the multitude can change a monarchical regime into an aristocratic or democratic one and vice versa, as we know happened in Rome.” The conclusion is “from what has been said it follows that political power, considered in particular, certainly comes from God, by means, however, of human deliberation and election, like everything “de jure gentium.”

This “jus gentium” is like a consequence deduced from natural law through human intervention. Clear in such theses of Bellarmine are the presuppositions of as many of the cornerstones of modern political and constitutionalist thought; the distinction between authority (good and necessary because it is ordained by God) and those who exercise it (human and therefore sinful, like those who are governed). This is the foundation of the conception developed in the bourgeois state whereby, precisely because rulers are not angels, checks are needed on them, as written in the Federalist Papers. Which led to the exceptional increase in the organization of liberal democracies, of the legal (and political) system of “brakes and counterweights;” and, likewise, to the impossibility of legal controls over the ruler (subject only to limitations of an ethical, religious and ontological nature i.e., of “natural law” not positive law, in any case not susceptible to coercion). This confirms at once the necessity of political power (by divine right) and the accidentality of the forms in which it is ordered and the subjects chosen to exercise it. It reaffirms the distinction between “ownership” of political power to the whole multitude, obliged to transfer it to one or more, by “natural right” (i.e., by objective necessity) and thus affirms the necessary character of representation; while the forms in which it is organized, which are not of natural right (see above) depend on the free will of the multitude, which can always change them precisely because they are not of natural right but de jure gentium. And it can all be done by decision (by an “act”) which also anticipates the conception of modern constitutionalism that sees the constitution (mostly) as deliberation of the constituent power.

The latter theses have also transited into law and, even more, into the (political and) legal doctrine of the liberal democratic state. To recall one, the most important—in the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen, Article 3 thus proclaims “Le principe de toute souveraineté réside essentiellement dans la nation. Nul corps, nul individu, ne peut exercer d’autorité qui n’en émane expressément.” This statement in which the “multitude” is replaced by the Nation, always contrasted with the pouvoirs constituées, was repeated in similar forms in all subsequent French constitutions (except, of course, in that of 1814).

Hauriou argues that law does not escape the rule that, behind every physics, there is a metaphysics. Which normally does not manifest itself; rather it is carefully concealed by a layer of law, and so it remains, if one stops at the appearance (as is normal in a normal situation, that is, almost always). But “when the legal covering fails, as in de facto power, one falls back to the metaphysical or theological background.” Which happens when a radical revolutionary change is produced. For modern France this has been repeated—Hauriou wrote in 1929—at least four times since the revolution of 1789. De facto power tends to become—and mostly succeeds in doing so—a power of law: but to do this a law is completely unnecessary: “Un gouvernement provisoire n’a jamais fait voter une loi pour déclarer qu’il devenait légitime.” In such affairs, the régle de droit finds no use; indeed much of the law created by such governments, even if not ratified, is often validated by jurisprudence: this is because, Hauriou writes, government is necessary, a de facto government is better than no government, and power is a natural thing and of divine origin. He concludes, “Tel est l’enseignement de la morale théologique; tel est celui de la sagesse et telle est la pratique.”

One wonders why the conception of divine providential law is so conspicuously present in the theory of law and the bourgeois state. The answers could be several and competing: that indeed modern philosophy, especially that of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries is largely tributary to the natural law and theology of Second Scholasticism, and that through this “secularization” it came to the French constituents and thence to European constitutionalism; or because it was a Catholic nation such as France that made the revolution, and in it there had great importance a priest such as Abbé Sieyès, educated by the Jesuits. But the argument that seems most important—and preferable—is that such a conception, as Hauriou has well seen, allows the relationship between fact and law, being and ought-to-be, power and order, transformation and preservation, freedom and necessity, to be explained in a manner that is both realistic and rational. In fact, the different conception of supernatural divine law carries in itself defects similar to those Hauriou identified in the theories of law, contemporary to it, of Duguit and Kelsen, which he lumped together as static systems.

Such systems “willingly present themselves as objective, and indeed they are so because they eliminate the work of man, which is the source of the subjective; but they are above all static because of their erroneous conception of the social order, and under this static aspect we shall examine them because it makes manifest their incompatibility with life.” In Kelsen’s system, the legal and state order is considered the expression of a categorical imperative of practical reason; moreover, it is an “idealistic monism,” where state and law are confused. And, indeed, it is the static profile that prevails over the dynamic one. Thus, while such a theory succeeds in avoiding the conception of domination power, it does not avoid the domination of a categorical imperative involving a necessitating social order.

But the yoke of such a philosophy “serait pour le droit pire que celui de la théologie. La théologie catholique pose le primat de la liberté humaine: l’ordre divin se propose à l’homme par la grace.” Instead, in Kelsen’s system the order of “idealist pantheism” imposes itself as a constricting necessity. Hence, he concludes that in France he will have no luck “parce que ses tendances sont inconciliables avec celles du droit. Seule une philosophie de la liberté créatrice est compatible avec lui.” As for Duguit’s system, this takes as its starting point “la notion positiviste d’un ordre des choses sociales conçu comme le prolongement de l’ordre des choses physiques. De cet ordre des choses découlent des norms.” His great concern is to suppress power as the source of law. But this implies the static nature of the system, for the negation “du pouvoir subjectif de création du droit, le mouvement juridique, qui résulte surtout des forces subjectives, est arreté.” And, except for the cases of exceptions in the system. le droit ne peut se développer que dans la mesure des normes établies ou par l’établissement de nouvelles normes, mais c’est là une formation coutumière d’une extreme lenteur. Le système tend donc vers l’immobilité coutumière.” And he concludes from this that Duguit’s system is, like Kelsen’s “impropre à la vie.”

Indeed, in analyzing the consequences of the doctrine of supernatural divine right, one sees that, obviously for different reasons, it has the same drawbacks as those of Kelsen and Duguit. First of being static, since it crystallizes power relations and the rules for accessing them: he who has the power, has the right to command and to demand the obedience owed to him; any innovation is, not coming from he who holds the power, against divine right. Second, to put law before fact, which is precisely the opposite of what happens, for example in international law, where it is the fact of a state’s control (of population and territory), and not the legality of the settlement, that makes a revolutionary government an international interlocutor. If this were not the case, if one were to rely on the criterion of “supernatural divine right” (or pure “normative” assessment), Italy would have to be represented by a Savoy, Germany by a Hohenzollern and Russia by a Romanov. With the effect of pitting law against reality (and life); and making (also) the one unfit to address the latter. There is, moreover, a radical antithesis between Bellarmine’s distinction between authority and ruler (sinner) and that “vous étes des dieux” addressed by Bossuet to monarchs: which Hauriou rightly considers compatible only with absolute monarchy.

But the fortune of the conception of divine providential law is not only that it is “dynamic,” that is, realistic, but also that it explains the relationship between force and law, again in realistic terms. By deeming necessary the living in society and under a government but not its forms, it is open to innovation and the nomogenetic character of force, aimed at ensuring communal existence The rate of innovation this introduces serves to ensure its adaptation to the changing conditions of history, that is, its vitality. The realism of the conception under consideration is given essentially by the relationship outlined between natural law and jus gentium; in other words, between necessity and human freedom.

Recognizing that among the laws of nature is that of associating under a political government, Christian theology had identified one of the “constants,” defined by Miglio as the regularities of politics; as such unchangeable by the human will. Which, conversely, the “absolute” utopias believe they can modify, believing they have found “the solution to the enigma of History,” as the young Marx wrote; from history punctually belied, with the almost simultaneous collapse of almost all the regimes of real socialism, which were the realizations of that utopian vision.

But the belief that one can alter “regularities,” which is particularly clear in the case, like communism, of realized utopias—and promptly confined to the archives of history—is not exclusive to those, being present albeit to a more limited extent in other ideological conceptions, from certain types of pacifism to liberal fringes (not to liberalism, which retains a realist approach, as is evident from the “problematic” conception of man, derived from both Christian theology and political thought).

This immutability of the “constants” is contrasted with—and complements—the mutability of political forms, which are left to the power-and therefore the freedom-of human communities: this conception founds political freedom in the primary sense of the free “conformation” of the social and political order: in this is the specification, within the community of St. Thomas’ definition “Liber est qui sui causa est”: not to be limited except by divine (and natural) law, from which no one is dispensed. In this way, this conception grants to human communities all possible freedom, without any legal constraint except self-imposed by them.

Moreover, returning to the character of dynamism, it is worth mentioning that Hauriou, like other great jurists, does not link the concept of social order to “conformity” between norms and behavior, that is, to something static, but to something quite different, namely, to the “slow and uniform” movement of the human community. He returns to this concept several times, specifying that it is the movement “of an ordered whole and is the result of organization and results from what order is essentially organization;” and to clarify the concept he resorts to a biological comparison. Just as living organisms retain form (which changes, but slowly), while subject to extremely rapid turnover of cells and tissues, so do social groups behave like living organisms, provided they are organized, and last for centuries retaining a similar form, even though the “cells,” i.e., humans, are completely changed. And for such reasons, that is, (also) because of the ability to adapt to political and social life, he judged that the doctrine of divine providential law, by placing the origin of power above the social collectivity and anyone else, does not lead to any absolutism, and is therefore the most conducive to freedom. Not only to individuals, but also to that of the community to give itself the form it prefers.

We had begun by asking why in French doctrine at the turn of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries the doctrines of divine right, and in particular the “providential” doctrine, are carefully considered. Within the limits of this paper, we have identified a few reasons, mostly from those already indicated by Hauriou himself, relating to the essence of the social and political) order and relationship.

There is also another reason, implicit in the doyen’s thinking: it is that Hauriou was a staunch supporter of Western civilization (and thought), to which he devotes some of the most interesting pages, even for those who read them today. “Western civilization,” he writes, “by its strength, its activity and its ideas, dominates the world, but it has not completely assimilated it. At the same time, it is undergoing one of its internal crises; many doubt the value of its cornerstones. Although the sedentary civilization will probably survive in partially different forms, the European peoples are in danger of disappearing in a blizzard, after much suffering. At this juncture it is not the external, but the internal enemy that is the most dangerous; therefore,” Hauriou continues, “Western civilization should not be doubted, for what it achieved “en fait d’oeuvres de beauté et de vérité intellectuelle, est devenu classique, c’est-à-dire a réalisé l’idéal humain.” Communism itself, then newly realized in Russia, seems to him incompatible with sedentary and individualistic society, and, rather than an “extreme” phase of modernity, it seems to him a return to the legal forms typical of nomadic societies.

In contrast to the attention French scholarship pays to the conception under consideration, it is rare to read similar considerations elsewhere, especially in Italy. For example, consulting the entry “Democracy” in the classic “Dictionary of Politics,” one can read everything from Herodotus to Rousseau, from the democracies of the ancients to socialist democracies (and beyond): however, any mention of this one, which has probably influenced the form of the contemporary state no less than the others and whose traces are (largely) present in our Constitutional Charter, is missing; and, which is equally relevant, the consequences of this one are, today more than yesterday, and despite all efforts to the contrary, common sense.

Teodoro Katte Klitsche de la Grange is an attorney in Rome and is the editor of the well-regarded and influential law journal Behemoth.

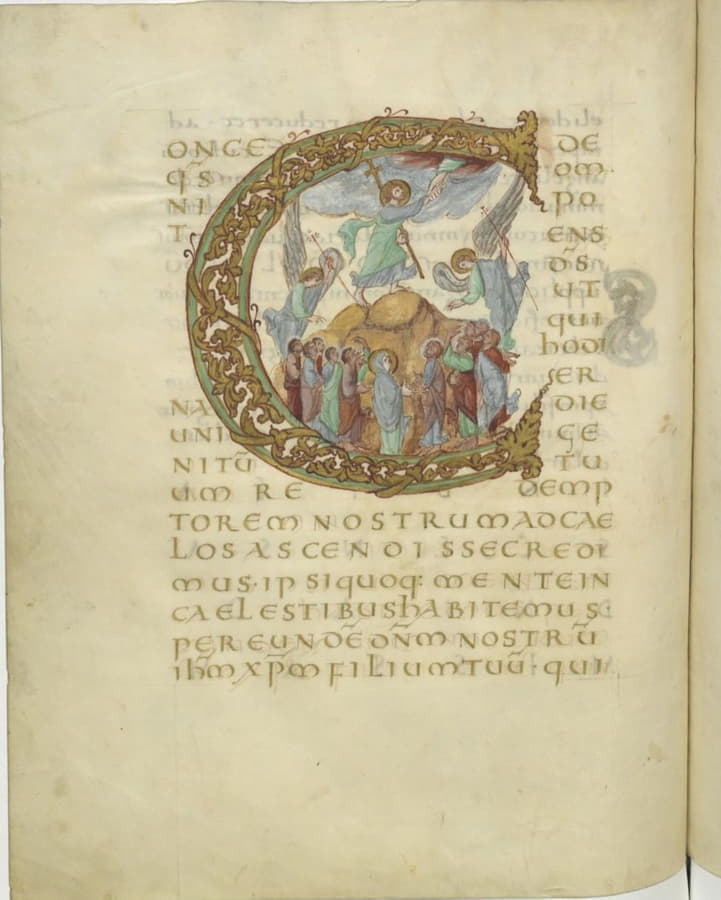

Featured: The Ascension, in the Drogo Sacramentary, Folio 71; ca. 845-855.