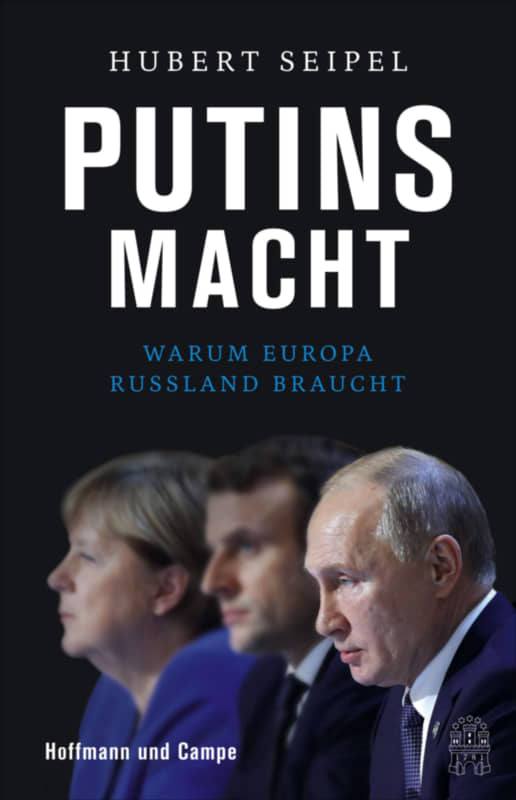

This excerpt is from Putins Macht: Warum Europa Russland braucht (Putin’s Power: Why Europe needs Russia), by Hubert Seipel, who is a well-known German journalist.

But what sets Seipel apart is the fact that he is the only Western journalist to have direct access to President Vladimir Putin. Therefore, his book is filled with great insights into the character, personality and geopolitical thinking of the man who currently leads Russia.

We are very grateful to El Manifesto for the opportunity to present this excerpt.

Learning from Capitalism

For Vladimir Putin, the missile shield is an example of the West’s failure to appreciate the way Russia has peacefully overcome the fall of the Soviet Union. Putin is quick to adapt to the negative historical judgment on “real socialism,” but he still considers that the fall of the Soviet Union was negotiated by its leaders in an unprofessional manner; that the Soviet Union, in December 1991, ceased to exist in less than two weeks after the presidents of Russia, Ukraine and Belarus announced its end. A few days later, the flag with the hammer and sickle gave way to that of the tsarist-era double-headed eagle.

When Putin was in charge of the economy of the St. Petersburg executive, he quickly understood that capital, in the era of globalization, does not move easily except in regions where it feels comfortable and secure. Russia had a number of advantages: tax rates were very low, as were wages, and the Russian people, despite miserable living conditions, were peaceful. However, Putin also saw very clearly, during this rapid initiation to capitalism, that millionaires should pay taxes in their country and respect the actions of the state.

But it is not only the feeling of having been abused that angers Putin. The lack of respect for Russia’s vital interests is, for him particularly hurtful, especially when the country shows signs of weakness. Putin confessed to me, during hours of conversation, without taking a breath, except to drink a little vodka, how the strategic configuration of Europe has been modified, without taking into account Russia’s susceptibilities. When the Warsaw Pact collapsed with the fall of the Soviet Union, NATO took the opportunity to develop with expansive madness… Poland, the Czech Republic, Hungary, the Baltic States, Romania, Slovakia and finally Croatia and Albania, “when we had been promised, on the occasion of German reunification, that there would be no extension of NATO.”

From Lisbon to Vladivostok

Vladimir Putin’s political objective is to create an economic space from Vladivostok to Lisbon. At the end of November 2009, he chose the Adlon Hotel in Berlin to present his vision, to German businessmen, of a common economic zone, with the European Union. A free trade zone without customs duties, a common industrial policy and the abolition of visas were just a few of Putin’s proposals. Both sides would benefit, including Russia, of course. “Because Russia, after the breakup of the Soviet Union, has not had access to its main export markets. Problems have arisen with transit countries, which have tried to take advantage of their monopoly situation to extract unilateral advantages. This is a source of disputes.”

Putin insisted on a central point in his thinking: “It is of paramount importance that we learn to respect each other’s strategic interests through deeds and not just words.”

Two years later, Putin was still convinced of his proposals. At the end of 2013, in Sochi, he explained to me the reasons for his strategic reflections. “A rapprochement with Europe is not, in principle, bad for us. We have the natural resources and Europe has the know-how. We would both profit in the long term.”

His goal has always been an agreement with the European Union and Ukraine to modify the technical standards of Russia and countries such as Belarus and Ukraine, so that they become compatible with those of the European Union and thus competitive. Leveling the economy—and responding, at the same time, to the expansive policy of the West—is, for him, nothing more than a question of time, equal opportunities and increased investments. This is the reason why Putin insisted on joining the World Trade Organization, which decides by means of its binding international rules what is authorized and what is not. After several decades of arduous negotiations, Russia was able to overcome the obstacles and was admitted as a member in 2012. The EU’s simplistic reaction of rejecting Russian proposals before even examining them provoked his anger. “They have been repeating one thing to us for years: you must not interfere in Ukraine’s affairs. We do not intervene in your relations with China and you should not intervene in our relations with Canada.”

Putin regards the attempt to separate Ukraine economically from Russia as a political maneuver against his country; and the technocratic point of view of Brussels, for which Russia’s relations with Ukraine are of no importance, he sees it as a deliberate strategy. As a political man, he is appalled that initiatives of such importance, with enormous consequences for the neighboring country, can be taken without negotiation, but exclusively bureaucratically. “It is not difficult to realize that our relations with Ukraine are different from those between Brussels and Canada, as these really have no complexity,” Putin laconically lamented.