In the time of the “night of the world,” visions of being installed in a naive realism and flooded with high ideological doses, which dissolve the possible in the existing, prevail as the only horizon. The imposed ontology, the one functional to the dominant class, is centered on the untransformability of the order of things and, at the same time, on the primacy of the technical act, which instrumentalizes entities with a view to the infinite increase of the will to power.

As we have tried to show in Idealismo o barbarie, the first revolution consists in the change of the ontological frame of reference and, specifically, in the variation of the coefficient of inevitability. To the mystique of necessity and the absolutism of the given reality, that is to say the two ontological principles on which the hegemony of the dominant pole is founded (according to the theorem of there is no alternative), it is necessary to oppose an ontology of historical possibility. The latter must be based on a conception of being not as an unmodifiable datum, but as history and possibility, therefore capable of transformation through the process of collectively organized subjective praxis.

In conformity with the subject-objective ontology theorized by classical German idealism, the Object, far from being res separata to which the Subject must adapt (adaequatio rei et intellectus), is always mediated by the Subject itself: fatum non datur. With Hegelian syntax, it is necessary to think die Substanz als Subjekt (“Substance as Subject”), being as mediated by subjective doing. Consistent with these general ontological foundations, reality is a process in act—with Hegel, Wirklichkeit and not Realität—and does not coincide with that which simply “is”: rather, it is the sum of that which “is,” that which “has been,” and that which, from that which exists and that which has already been, “could be.” Thus, in what we would call with Marx the present “realm of strange beings to which man is subjugated,” to act means to rely on the free decision to realize the unfinished possibilities of history itself, transforming the past into a reservoir of virtualities that can be implemented through the concrete encounter between anticipatory decision and transformative praxis: in Heidegger’s words in Being and Time, “the decision, which returns upon itself and is self-transmitted, then becomes the repetition of a transferred possibility of existence,” revitalized and placed in tension with the present in which it finds itself.

The repetition of the past, therefore, is not the ritual celebration of that which no longer exists, nor the sterile seduction exercised by a past that is believed to be able to return as it was. It is, on the contrary, the active gesture of transmitting and recalling the possibilities preserved in that which has been and which can incubate multiple possibilities for the future: die Wiederholung ist die ausdrückliche Überlieferung, das heiBt der Rückgang in Möglichkeiten des dagewesenen Daseins, “repetition is the explicit transmission, that is, the return to the possibilities of being-there-that-has-been-there”. Again, with Heidegger’s syntax, Dasein (“being-there”)—both of the individual and of peoples—is a synthesis of the three dimensions: of the future of the project, of the present of the decision and of the past of the origin. And, turning now to Hegel, it is the bearer of historical consciousness and of the consciousness of contradiction as the root of being.

Even if it is different and, at times, incommensurable with respect to that of Being and Time, the subjectivity questioned by Hegel in the pages of the Phenomenology of Spirit has in common with the former the historical temporality in its tri-articulation, assumed as the very foundation of being in the world of man. The Hegelian Subject is, by its essence, the bearer of a progressive historical consciousness. It gradually conquers the historical consciousness of itself as a unitary subject, which objectifies itself in temporality according to increasingly rational forms. Such forms are, in turn, conceived in their authentic subject-objective nature of historical products, and not of given and presupposed suchness.

The conception of Substance as Subject, defined in the Phenomenology of Spirit, implies that Totality is given as the movement of its own development and that the Concept is resolved in the dynamic that makes it become truly itself; with the Phenomenology, “it is Spirit itself that moves: he is the Subject of the movement (er ist das Subjekt der Bewegung) and, at the same time, the movement itself, that is, the Substance through which the Subject passes,” which therefore exists indispensably in the dimension of time and of becoming, that is, of its history. That is precisely why the Spirit is time or, as Hegel specifies, erscheint der Geist notwendig in der Zeit, “the Spirit necessarily manifests itself in time,” as processual self-consciousness and as a series of practical objectivations.

Beyond the obvious differences, both the Dasein of Being and Time and the communitarian Subject of the Phenomenology of Spirit are equally “discharged” by the logic of the flexibilization of coessential identities to the new spirit of the de-anticized and absolute system of needs. The homo instabilis, co-originary with respect to the new made-precarious anthropological profile, cannot decide freely since, more and more ostensibly, he appears as an external and directed pawn, considered in the same way as all other commodities on demand. It does not have, Hegelianly, historical consciousness and communitarian eticity, nor, Heideggerianly, projective temporality and remembrance. It cannot enjoy a free ek-static projectuality directed to the future, condemned as it is to the precarious life that, by its essence, denies the very foundation of ek-sistence as a claimed transcendence of the present to reach desired futures.

Finally, the postmodern homo instabilis is deprived of mnestic memory and of his own historical roots. The absolute mobility to which he is condemned renders him uprooted and deterritorialized, projected in the pure ahistorical and aprospective immanence of the eternal flexible present, of which he is a nomadic and unstable inhabitant. One of the fundamental bases of Dasein, whether individual or collective, is thus deconstructed.

The “global I” of homo instabilis, deprived of memory and tradition, is therefore mutilated of soul, if we take for granted, as St. Augustine affirms in his Confessions, that sedis animi est in memoria. At the same time, the sphere of prospective and the mnestic dimension is dissolved, that is, the capacity to recall tradition and to draw inspiration from it in a projective key (“the self is memory,” Hegel reminded us). Only the mens instans survives, as Leibniz called it, the “instantaneous mind” incapable of remembering and projecting, of thinking and imagining, entirely absorbed in the reified immanence of calculation and know-how. The construction of the identities of individuals and communities is always based on the stratification of experiences, on their sedimentation in the form of memory. There is no cultural identity in the absence of historical memory. Uprooted man is deprived of historical consciousness and lives, with a necessary false consciousness, the time of flexible accumulation as a natural and eternal destiny. “The ahistoricity of consciousness is the messenger of a static state of reality,” as Adorno pointed out.

The humanism of classical civilization, expressed, for example, in Cicero’s Brutus (§ 257), is denied by techno-nihilistic barbarism: non quantum quisque prosit, sed quanti quisque sit poderandum est.

It is a question, mutatis mutandis, of the same distinction established by Kant, in the Foundation of the Metaphysics of Morals (1785), between price and dignity: that which has a price—Kant explains—can be exchanged for its equivalent, while that which has no price, having no equivalent, is that which possesses only dignity.

Diego Fusaro is professor of the History of Philosophy at the IASSP in Milan (Institute for Advanced Strategic and Political Studies) where he is also scientific director. He is a scholar of the Philosophy of History, specializing in the thought of Fichte, Hegel, and Marx. His interest is oriented towards German idealism, its precursors (Spinoza) and its followers (Marx), with a particular emphasis on Italian thought (Gramsci or Gentile, among others). he is the author of many books, including Fichte and the Vocation of the Intellectual, The Place of Possibility: Toward a New Philosophy of Praxis, and Marx, again!: The Spectre Returns. This article appears courtesy of Posmodernia.

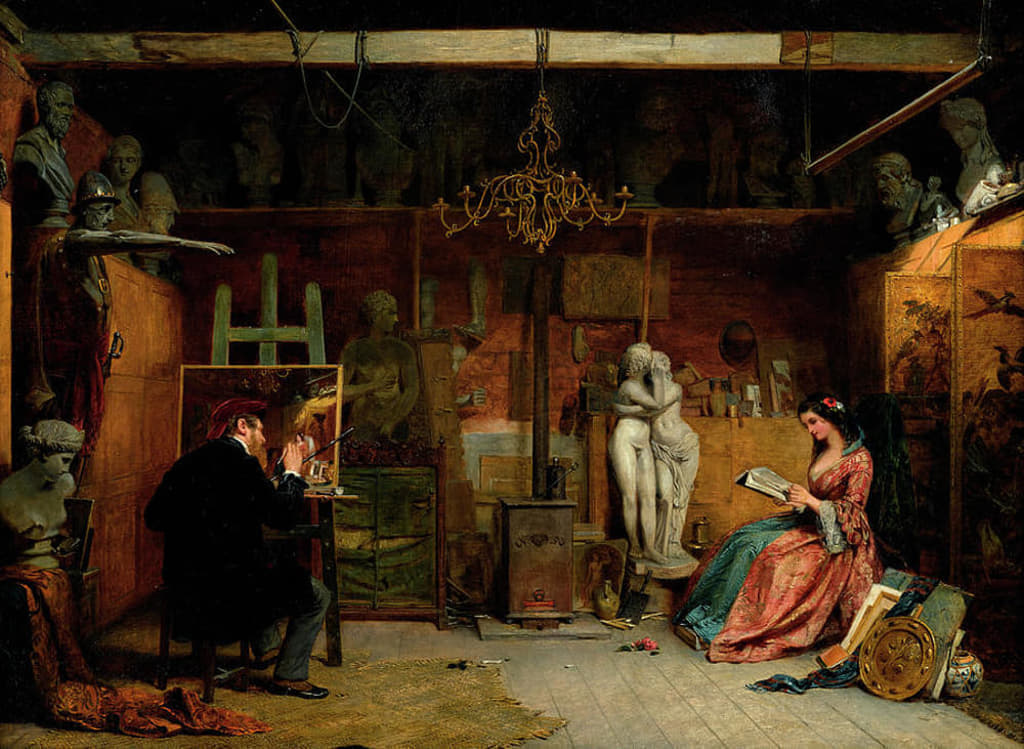

Featured: The Painter’s Studio, by James Digman Wingfield; painted in 1856.