The recent victory of Giorgia Meloni and her party, Fratelli d’Italia, leading a coalition described as “conservative,” in Italy, is the latest episode of the advance in the nations of Europe of parties and movements that we qualify as “conservative populism.” Obviously, in Spain, the reference of this type of party is Vox. In this article we intend to analyze the possibilities and limitations of these political forces from the ideological perspective of a radical and sovereignist Hispanism, with a reasoned and reasonable criticism.

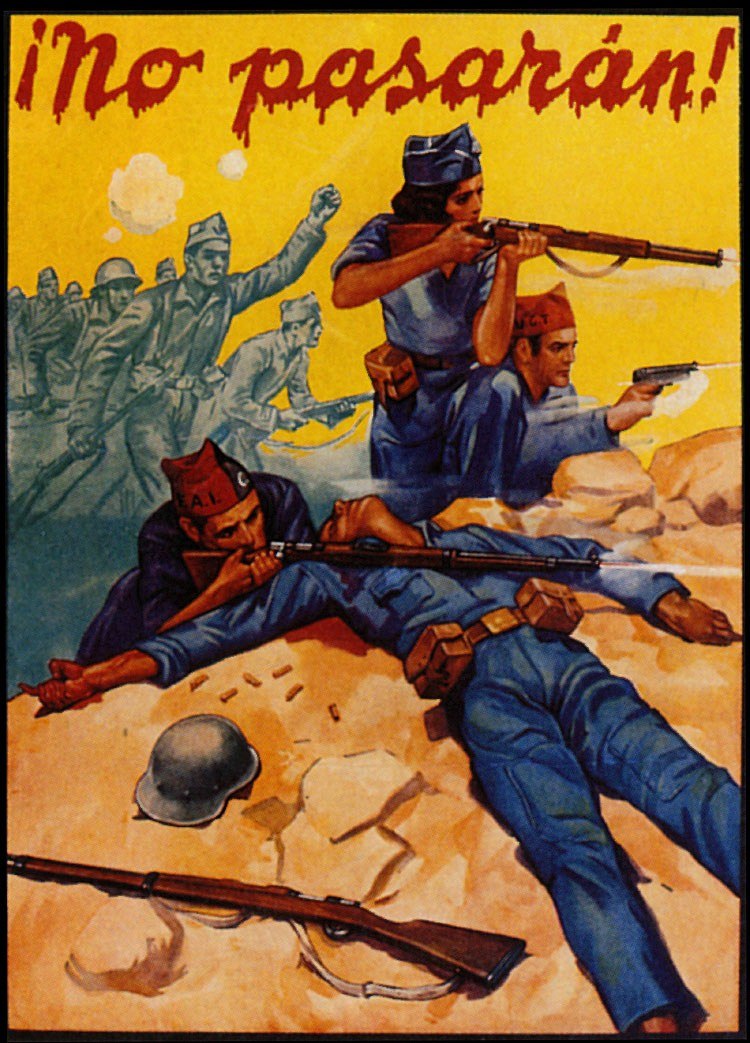

First of all, we will shred the stupid accusation, repeated ad nauseam by both the champagne Left and the liberal Right, that these parties are “fascist.” To do so, we will analyze what fascism really was, and bearing in mind that this term can have two real meanings: Mussolini’s regime in Italy, which ended with the defeat of that nation in World War II; or also, in a much more generic way, a set of political movements that occurred in Europe and Latin America in the interwar period and that, with some exceptions, also disappeared after World War II.

Regarding the accusation, also repeated ad nauseam, of being “ultra-right” or “extreme right,” we are not going to bother, since these terms are authentic “flatus vocis,” without any real content. In the usual political chatter we have heard how the PP, C,s, ETA, Catalan separatists, judges and the sumsum corda were accused of being “extreme right”. For the sake of mental clarity, we will not enter into this debate.

Italian fascism, from which comes the generic name given to other similar movements, was born as a split on the left of the Italian Socialist Party, of which Mussolini was a prominent leader. The main point of belligerence was Italy’s intervention in World War I, a thesis defended by Mussolini and his supporters against the “pacifism” of the Socialist International. Once the war was over, and Italy was among the victorious powers, the interventionists considered that it had not received, on the part of the other victorious powers, the economic and territorial compensation to which it was entitled.

All this ended up provoking the split, and the formation of the “fascios di combatimento” first, and later of the National Fascist Party, absorbing a good part of the so-called “national syndicalism,” of Sorelian inspiration, and also the nationalists of Corradini, of a more conservative tendency. In the images of the famous “March on Rome,” all the Fascist leaders accompanying Mussolini were people who came from Sorelian syndicalism.

Italian fascism always perceived itself as a revolutionary movement, opposed to liberalism, and which differed from Soviet communism by opposing the Nation as a political subject to the social class. Although on coming to power the movement became more moderate and “right-wing,” to the point of tolerating the monarchy, these revolutionary premises were always present, and re-emerged with force in the proclamation of the Italian Social Republic, even in the midst of the World War and with the Allied invasion of Italy.

The fundamental characteristics of this regime were:

- Single Party: the National Fascist Party.

- Corporate economic regime. Although there were state enterprises, private ownership of the means of production was admitted, but with rigid state control. Corporations brought together unions and employers with state presence and control.

- Secularism. The regime was NOT confessional, although it respected Catholicism as the majority religion. This secularism was not an obstacle for the signing of the first Concordat with the Holy See, with the recognition of the Vatican State.

- Expansionism. The regime was in favor of colonial expansion in Africa, hence its intervention in Abyssinia.

- Vague appeals to the heritage of Rome, and affirmation of the Mediterranean against the Anglo-Saxon.

Curiously, the only major movement outside Italy to claim the term “fascist” was Mosley’s British Union of Fascists, which was also born out of a split in the Labor Party.

It is evident that none of these elements, beyond vague appeals to national sovereignty, is present either in Giorgia Meloni’s party, or that of Salvini, nor, much less in Vox. We can only find echoes of state interventionism in Le Pen’s Rassemblent National. And this is so for two reasons—first because their ideological sources have nothing to do with each other (none of these parties comes from the left); but, above all, because the political, economic and geopolitical conditions of today’s Europe have nothing to do with the Europe of the interwar period.

Let us first analyze the conditions in which these political forces have emerged. We will then look at their successes and limitations, and finally, the possible positions of dissident movements in the face of the emergence of these forces.

From our point of view there is a fundamental event, which completely changed the political paradigm, which is the collapse of the USSR, and which opened the doors to ideological post-modernity, and which gave wing to the project of a unipolar world, with the USA as the hegemonic power, and the “end of history” as an aureole myth.

However, before this fundamental event, there are a series of issues to comment on, of events that mark the path in some way. The first was the appearance of the so-called Frankfurt School, which began to take shape in the years prior to World War II in the Weimar Republic, but which reached its maximum influence in the 1960s, and whose most paradigmatic representative was Herbert Marcuse.

The thinkers of this school were all of Marxist formation, although most of them militated in the German social democracy and not in the communist party; but they made such a deep criticism of Marxism that they emptied it of content. Their thesis was that the working class had become bourgeois and lost its revolutionary potential; and, consequently, it was necessary to look for new revolutionary “subjects” in the oppressed minorities and/or those who, because of their way of life, questioned the “status quo”: women, homosexuals, immigrants, students. In fact, the path of abandoning the class struggle and the beginning of the so-called “partial struggles” began.

These ideas were the theoretical basis of the so-called “May ’68” student revolts in many universities in Europe and the United States. Although the movement arose in “progressive” American universities, such as Berkley, it had special repercussions in France. It should be noted that, in France, the movement was driven by situationists (anarchists), Trotskyists and Maoists, but never had the support of the PCF loyal to Moscow.

This movement was hardly revolutionary. It responded to the demands of capitalism to generate new consumer habits, and to combat traditional morality, which had become an obstacle to mass hyper-consumption. The foundations for the consumerism, hedonism and nihilism that characterize postmodernity began to be consolidated in this movement.

Another fundamental event occurred in the 1980s, with the emergence of political neoliberalism under Ronald Reagan in the USA and Margaret Thatcher in the United Kingdom. Neoliberalism, as a reform of classical liberalism, had been incubating since the 1940s (Walter Lippmann Colloquium, Montpelegrin Society), Hayek being one of its most important theoreticians. Its political subject is to be found in the individual, but not in the rational-Cartesian individual of classical liberalism, but in the post-individual consumer. Contrary to classical liberalism, neoliberalism considered that the market was not a spontaneous phenomenon, and advocated an “interventionist” state, in the sense of acting to create these market conditions.

On the other hand, this neoliberalism advocated abandoning all Keynesian and social protection policies, since it conceived social life as a struggle of “all against all,” and considered that social protection policies encouraged laziness and irresponsibility.

The fall of the USSR opened up an excellent scenario for these proposals. Capitalist states no longer needed to prove that their workers lived better than those in socialist countries. Liberalism, mutated into neoliberalism, had been left alone when the main referent of socialism collapsed; it no longer had to present itself as a political theory or justify itself.

The collapse of the USSR meant the end of the Cold War, and gave rise to the United States to cherish the idea of a unipolar world, subject to its empire. As a consequence, we had a series of phenomena:

- The increasing pressure of international organizations, which were nothing more than tentacles of the Anglo-Empire, on the sovereignty of states and peoples.

- The increase of immigrationism, whose function, apart from providing cheap labor and creating social dumping, is to dilute the identities of nations and peoples.

- The domination of globalism and its vicarious ideologies (Agenda 2030) over the media, educational programs, universities, cinema, television series, in an increasingly suffocating proportion. Globalism is a sort of synthesis between neoliberalism, social democracy and the champagne left, which allows it to present and perceive itself as left-wing and “progressive,” but it is nothing more than a tentacle of the Anglo-empire.

- The consolidation of the EU as a political-economic branch of the Anglo-empire for the control and submission of Europe and NATO as a military branch of the same.

- Economic sanctions, isolation and destructive war against any state that tried to oppose globalism: aggression against Iraq, Serbia, Syria, Libya by the USA and its allies/vassals. Economic sanctions against Poland and Hungary. “Warnings” from van Der Leyden to the Italians of what can happen to them if they do not vote “correctly.” Humiliation of Greece, etc. The current war against Russia is part of these processes.

All this has generated in many European nations significant pockets of discontent in large sectors of the population. The destruction of the middle classes, the conversion of the proletariat into the “precariat,” the growing fiscal pressure that does not translate into improved services, the feeling of conservative sectors of the population that their values are constantly criminalized, the problems generated by uncontrolled immigration, insecurity and delinquency, the growth of the squatting phenomenon—and the inability of the left, social democrats or champagne lefists to channel this discontent, as they are part of the System that has provoked it.

In this context, the conservative and populist parties and movements have had the ability to capitalize on this discontent. With all their differences, which they have, parties such as Meloni’s, Salvini’s, Le Pen’s, Vox or Alternative for Germany (AfD0 have ridden their electoral successes on these sectors of the population that felt orphaned of representation.

However, it is one thing to channel discontent and quite another to have the capacity to act on its causes. This capacity depends on the real power that one has; but also, and above all, on the proposed objectives.

In political action we must distinguish between what we want to do and what we can do. It must be understood that, many times, the deficiencies and the distance between proposals and realities respond to this lack of power; but if what has been achieved is in line with what is desired, the political action is correct. A sovereigntist government, such as the Hungarian government, confronted with the European Commission, may have to give in on some things, but this is not due to a lack of will, but to a lack of power. We cannot deduce that this government has betrayed its objectives, but simply that it has not been able to fulfill them.

Now, in this case, my concern is not about the distance between objectives and achievements, but about the objectives themselves. All these parties agree in demanding from the EU more sovereignty for the states and less interference in their internal policies. This differentiates them from the liberal-conservative parties, such as the PP, which are absolutely surrendering national sovereignty to the Eurocrats. This is a very laudable objective, even if it is not entirely achieved, since it is to put a spoke in the wheels of globalism. Another objective is the development of a “cultural war” against the ideologies of the 2030 Agenda, and it is also very laudable, even if it is not 100 percent achieved.

However, none of these parties has clearly and distinctly demanded that the EU develop policies of its own outside of U.S. interests. None of these parties has viewed NATO as a threat to sovereignty equal to or greater than the EU itself. And, consequently, none of these parties has called for NATO’s exit from the nation in which they operate. And this is what is worrying.

The current situation, the war in Ukraine, the sanctions against Russia, the energy crisis, the sabotage of NS2, lowers many masks and has turned the cards upside down. Meloni rushed to affirm her support to Zelensky. Le Pen is silent. Vox, through the mouth of Rocio Monasterio, has accused Russia (against all logic) of sabotaging the NS2, while Santiago Abascal in a tweet (unless it is a fake) claimed that “the climate lobbies were financed by Russia.” It is best not to talk about the Poles. The only ones who have taken dignified positions, against sanctions against Russia, have been Orban and Alternative for Germany.

I insist. The worrying thing is not that they are not able to get their respective countries out of NATO; the worrying thing is that they do not even propose it—that they do not consider NATO a threat to sovereignty; that they do not see, or do not want to see, that all the ideological garbage of the 2030 Agenda, which they fight, comes from the USA; that it is an instrument of globalism, and that this globalism is nothing more than the ideological alibi of the Anglo-empire.

Having said all this, I am now going to focus on the Spanish case, that is, on Vox. There is a very interesting book by Pedro Carlos González Cuevas, Vox, entre el liberalismo conservador y la derecha identitaria, in which he advances the theory of “las dos almas de Vox” (the two souls of Vox). According to this theory, there would exist in Vox a liberal sector (sometimes extreme liberal), Atlantist, close to the American “neocon,” and another more sovereigntist sector, more interventionist in economy and closer to the identitarian approaches. I agree with this theory, but with an addition: it is evident that the liberal sector is the one that controls the party.

This duplicity, which in the future may generate crucial tensions, with an evident predominance of the liberal sector, not only affects ideological and international positions, but also national political action and strategic alliances.

A Hispanist and identity-based policy, for example, would be incompatible with being the crutch of the PP, since in the designation of the main enemy, fundamental in all political action, the PP-PSOE tandem, the two-party system and in general the 78 Regime, would be pointed out, and an alliance with the PP would be as unthinkable as with the PSOE. On the other hand, if we start from the extreme liberal premises, the designation of the enemy is different—the left and the nationalists are pointed out, and the PP is considered as a natural ally, to be “right-winged.”

It is evident that Vox’s strategy is the latter, which shows the absolute predominance of the liberal sector. This could end up having dire consequences from the electoral point of view, because if the electorate ends up seeing Vox as a simple crutch of the PP, it will end up transferring votes to the major party. The worst thing that could happen to Vox is a PP-Vox coalition government, since experience shows that in these cases the big party eats the little one.

But it must also be recognized that there are militants, middle managers and even deputies in Vox who are not on this line. If in the future their influence in the party were to increase, the party could change some of its positions in a notable way. I would also like to clarify that these ideological tensions have nothing to do with the Macarena-Olona affair. The tensions that this lady has provoked are framed in a matter of “ego” and personal ambitions, without any ideological dimension.

José Alsina Calvés is a historian and philosopher who specializes in political biography, the history of science and the history of ideas and edits the journal Nihil Obstat. This article appears through the kind courtesy of Posmodernia.