This is Part II of a series of three: Part I and Part III.

Introduction

Last month we learned who the American People are. Armed with this information, this month we explore the unusual situation America finds itself in at this moment. The bloodline People have collided with various interests who have confederated against them. International conspiracy, dubious health regulations, peculiar weather, and rioting are intelligible in this context. As we’ll see, in this, there is nothing new under the sun.

As discussed in my previous essay, we learned who the People are. Using legal, historical, and observational data it is evident the People refer to the constitutors of the various American states, i.e., those men who signed the charters, declarations, and constitutions of the 18th Century which asserted that Britain’s North American colonies were no longer under the Crown corporation’s jurisdiction. Additionally, their families (i.e., the Posterity so often mentioned in writings of the period) are also the People. Finally, so as the People’s posterity not turn into an inbred caste, the constituting People allowed for the occasional addition of talented outsiders through marriage or adoption. This is the reason, for example, why America’s ruling class pays such attention to their Ivy League colleges.

Wait, you interject. Am I saying that when the town mayor and state rep and governor and president and senator talk about the People, and doing the best for the People, and fighting for the People, and protecting and serving the People, that they are not jabbering on about me? Alas, my friend, this is so. Break out your Kleenex.

Larger Context

By the by, while my comments here explore the localized American situation, this knowledge is applicable to world events in general. It is true that there are ideological differences throughout governments. Wahabi Arabia, Red China, and Republican France, for example, all have different governing systems. However, the nations of the world operate using a largely interchangeable legal system. Lost, these last few centuries, among the personalities and speeches and philosophies; lost among passionate and abstract discussions of monarchy and democracy, has been the irresistible rise of the worldwide legal system.

All such systems have come about in more or less the same fashion as America. Namely, some determined faction of the bourgeoisie, a crew somehow locked out of the hall of powers, declare themselves a People, they fight some war to a successful finish, and then they spend the rest of their lives encouraging fellow travelers in other nations to do the same. Rinse and repeat for 300 years.

Our order, the Liberal order, is the order of the People; it is the order of shopkeepers and attorneys. Since that crew wiggled out from under the thumbs of princes and bishops in the 18th Century, they have spared no effort in building their system. Like the Romans whose legacy they pretend to, the People are brusque to their foes, merciless to compatriots who break ranks.

The present pariah statuses of North Korea and Iran, the rough demise of Saddam Hussain and Muammar Gaddafi are suddenly intelligible in light of these dynamics. Second and Third World peoples, forever rag-dolled by the worldwide People, are coincidentally the less legalized populations of the planet. Less do their daily transactions, behaviors, and movements pass through the ledger of bankers, less are they subject to barristers’ regulable STRAWMAN persons, than the rest of mankind. Better than through the lens of race or economy, the poor treatment of these poor peoples can be understood via the dynamic of who the People are, who plays along with them, and who does not.

This Moment

Knowledge of who the People are is a hard pill to swallow. It’s cozier to think that I am the People. Just thinking, That political hack is talking to me! gives me tingles for days. However, tingles aside, knowledge is power, and a mature man knows that even unhappy knowledge allows one to discern events more sharply. It is not a bad thing to be disillusioned.

2020 has been a peculiar year. Whatever Coronavirus is, a botched bioweapon attack, an unintentional lab leak, a seasonal flu nastier than normal, the press has strung out a mild public threat into the story of the year. A sickness easy enough to protect vulnerable men from, has turned into another Black Death, at least on Plato’s 24/7 T.V. wall. America’s racial tension, what tension there is, was something that was either already ably being addressed by local community organizations or so removed from most people’s experience as to be merely an abstract academic conversation.

This marginal problem sparked intestine protests whose necessity only rivals for curiosity their apparent ability to be turned on and off like a switch. A country which still can’t bring itself to call the 2007 crash a depression finds itself with 25% unemployment, and no one seems especially concerned. This startling statistic. and its indifferent reaction, is only bested by an odder development, that universal basic income has found a warm reception in the land of independence.

Christianity, the one social force with enough heft to counter the overreach of the state, has shown itself a toothless shell. Besides some plucky and scattered congregations, the Protestant sects have stood down en masse and, less forgivable, the Catholic Church has become a crouching client of the Federal government. Lastly, much like the rioting of 2020, the dial of nature seems to be cranked up this year with bomb cyclones, derechos, biblical locusts, and a West Coast endlessly aflame. What a year!

The Confrontation

As sure as we know the membership of the People, America’s present instability can be understood as a confrontation between the People and various resentful outside forces who have joined their interests. They include various New Men (i.e., in the Roman sense; those like the Clinton or Obama families who’ve only lately been grafted into the patrician class; they who have little love for the People, nor the People for them), state interests (elements lately called the “Deep State,” including HAARP), and tech and fintech businesses who are quickly overtaking the nation-state in terms of the resources it can marshal for its ends.

For the sake of ease, I will refer to this diverse clique as “technocrats” since digital interests make up the stoutest contingent of this confederation. Their near-term goal is to shove back increasing regulation; their larger aim is the end of the nation state. This is what they mean by the “Fourth Industrial Revolution.”

Historical Backdrop

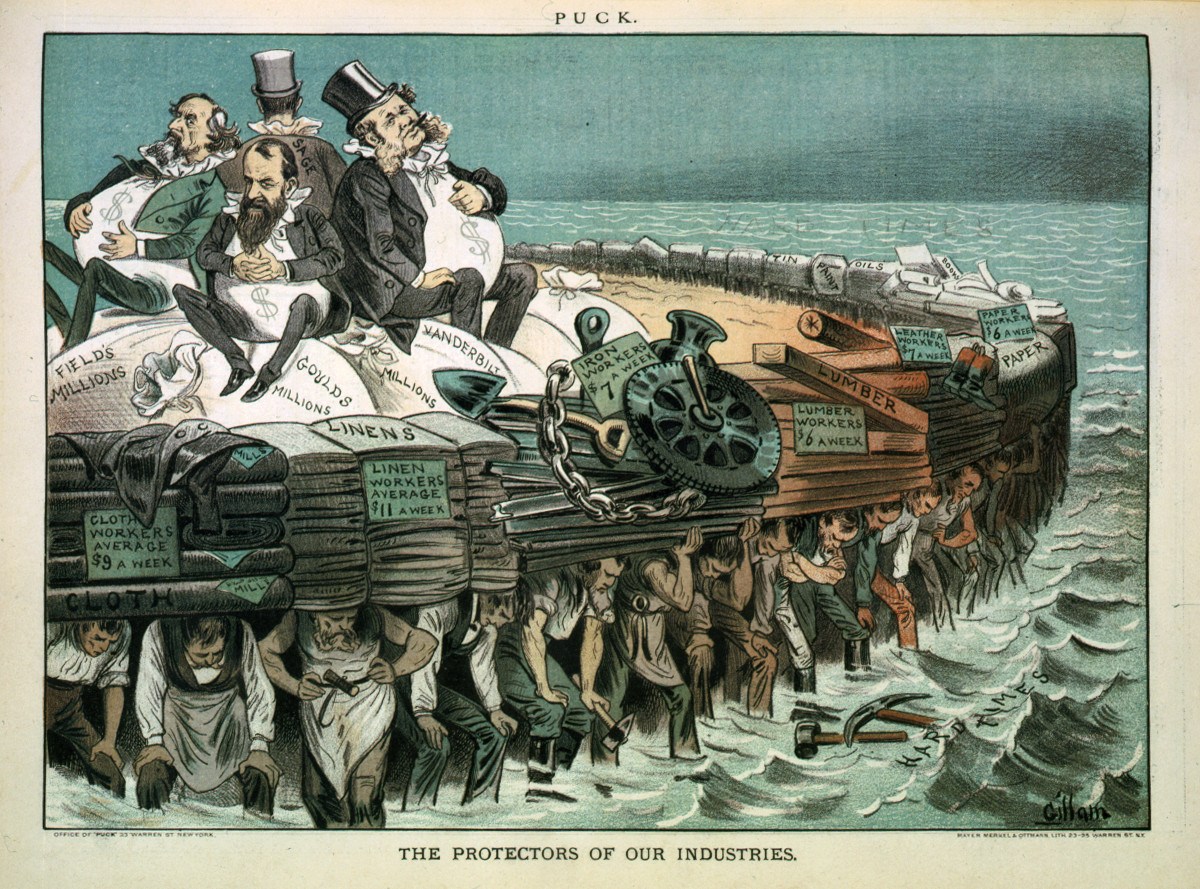

What we are seeing is nothing new. Rome saw this same confrontation happen. While American Indian, ancient Greek, and Medieval European systems influenced the government of 1787, the Roman Republic provided the largest example for the Founding Fathers to emulate. The 18th Century was a time peculiarly given over to reading ancient Roman history. As such, the Founders were aware of a tension which developed in the old Italian state, namely, the Roman People, the patricians, were slowly but surely outmatched by the rising equites.

Originally, the equite (i.e., cavalry) class consisted of the lower ranks of the patricians. Necessity eventually required enlarging the membership of the equites to include the wealthier plebeians. As the obligations of the state, the size of the army, and the sloth of the ruling class increased in the Late Republic, by around the time of the Servile Wars (ca.,100 BC) the equites ceased to have any real military role in the Roman army. All that remained to consume their days was wealth and ambition. By artful patronage and social entropy, as the decades wore on, the equites were able to gain the upper hand in their struggle with the Senate.

Nothing New Under The Sun

A like dynamic to Rome’s is at play in America. In place of the Roman People, we have the American People. Both are principally defined by bloodline membership. In place of the equites we have the technocrats. Both the equites and the technocrats found themselves under systems which restricted their growth. Just as the cursus honorum restricted the upper echelons of Roman rule to the patricians, so do various elements of the Liberal order hold back the dreams and schemes of the technocrats.

Just as the equites chafed under the mos maiorum, the ancient customs and mindset which undergirded the civic behavior of the Republic, so the technocrats languish under the assumptions of the Liberal order. We may save the specifics of Rome for another day, but to grasp the dynamics of America in 2020, we must remind ourselves of three points assumed by the present order. These are rationality, free speech, and the public space. The People’s nation-state system at least nominally believes in these things; the technocrats do not. Indeed, these three assumptions stand in the way of the latter’s greater growth.

Underlying Suppositions Of The Liberal Order

The present order assumes most men are mostly rational most of the time. It believes men can act with maturity and foresight to make intelligent decisions. Voting only works, after all, if the voters are rational. This is the chief reason Enlightenment states are heavy-laden with schools, libraries, and news media. Whatever raisons d’etre those fields may put out to encourage participation, the state’s interest is to form a well-equipped citizenry.

Connected to this rationality is the idea of free speech. All those well-informed citizens need to be able to compare notes in an unfettered fashion.

Lastly, we have the concept of the public space. This is this most mysterious concept of the present order. We’ve all heard the expression, but what does it mean? The concept of the public space arose in opposition to the Medieval order, an arrangement where everything was private. Private roads, private forests, private rivers, private courts, everything was the private property of someone. The Early Modern public sphere allowed all the little guys in a community to form a social force which could counteract any private interest which arose. This often abused, nearly forgotten concept is the assumption behind all Liberal states.

A rational electorate, freedom of speech, and the public space are hard-forged concepts which rank amongst the defining ideas of the Modern age. Those given to the notion of there being a “Postmodern” age point to the mid-20th Century decomposition of these assumptions as the definitive parameters of this term. However, the long rot of those concepts is only now manifesting. Even five or ten years ago online platforms at least made idealistic pretenses to excuse censorship. Now they shamelessly cite willfulness.

The Dynamic

The parallels between the Roman People and the American People don’t end with our earlier examples. As French Royalist Mallet du Pan famously noted, “The revolution eats its own.” And so it does. Lest we get sentimental and fall into the conservative’s bad habit of automatically siding with an older group over a newer, we remember that in their day the Roman People were just as much haughty upstarts as their American pretenders. They who ejected the Etruscan kings were themselves ejected by the next upstarts, the equites. Just so the American People – they who ejected the agents of the Crown are now besieged by a new social troop.

In the midst of this siege here’s the rub: America’s People have no more fight in them than Rome’s in the days of Marius. Like in the ancient world, America’s People have come to scorn their mos maiorum just as the Roman Senate did theirs. If this were not so they would never have permitted an admiralty statutory system to masquerade as law, they would never have tolerated jobberism among Americans, they would never have erected FBIs on top of CIAs on top of NSAs on top of DARPAs, if they believed the assumptions of their Liberal order they inherited.

Here the People stand in 2020: faithless, compromised, and indifferent. They may yet spur themselves on to one or two more victories before they’re through. They may well beat back the present assault. History trends as history does, though, and the odds are always with the determined. Between the People and the technocrats, there is no doubt who has stamina and who does not. We lose in any case.

John Coleman co-hosts Christian History & Ideas, and is the founder of Apocatastasis: An Institute for the Humanities, an alternative college and high school in New Milford, Connecticut. Apocatastasis is a school focused on studying the Western humanities in an integrated fashion, while at the same time adjusting to the changing educational field. Information about the college can be found at its website.

The image shows, “Main Street, Gloucester,” by John Sloan, painted in 1917.