Dr. Malthus, an economist, an Englishman, once wrote the following words:

“A man who is born into a world already occupied, his family unable to support him, and society not requiring his labor, such a man, I say, has not the least right to claim any nourishment whatever; he is really one too many on the earth. At the great banquet of Nature there is no plate laid for him. Nature commands him to take himself away, and she will not be slow to put her order into execution.”

As a consequence of this great principle, Malthus recommends with the most terrible threats, every man who has neither labor nor income upon which to live to take himself away, or at any rate to have no more children. A family, that is, love—like bread, is forbidden such a man by Malthus.

Dr. Malthus was, while living, a minister of the Holy Gospel, a mild-mannered philanthropist, a good husband, a good father, a good citizen, believing in God as firmly as any man in France. He died (heaven grant him peace) in 1831. It may be said that he was the first, without doubt, to reduce to absurdity all political economy, and state the great revolutionary question, the question between labor and capital. With us, whose faith in Providence still lives, in spite of the century’s indifference, it is proverbial—and herein consists the difference between the English and ourselves—that “everybody must live.” And our people, in saying this, think themselves as truly Christian, as conservative of good morals and the family, as the late Malthus.

Now, what the people say in France, the economists deny; the lawyers and the littérateurs deny; the Church, which pretends to be Christian, and also Gallican, denies; the Press denies; the large proprietors deny; the government, which endeavours to represent them, denies. The Press, the government, the Church, literature, economy, wealth—everything in France has become English; everything is Malthusian. It is in the name of God and his holy providence, in the name of morality, in the name of the sacred interests of the family, that they maintain that there is not room in the country for all the children of the country, and that they warn our women to be less prolific. In France, in spite of the desire of the people, in spite of the national belief, eating and drinking are regarded as privileges, labor a privilege, family a privilege, country a privilege.

M. Antony Thouret said recently that property, without which there is neither country, nor family, nor labor, nor morality, would be irreproachable as soon as it should cease to be a privilege; a clear statement of the fact that, to abolish all the privileges which, so to speak, exclude a portion of the people from the law, from humanity, we must abolish, first of all, the fundamental privilege, and change the constitution of property. M. A. Thouret, in saying that, agreed with us and with the people. The State, the Press, political economy, do not view the matter in that light; they agree in the hope that property, without which, as M. Thouret says, there is no labor, no family, no Republic, may remain what it always has been, a privilege.

All that has been done, said, and printed to-day and for the last twenty years, has been done, said, and printed in consequence of the theory of Malthus.

The theory of Malthus is the theory of political murder; of murder from motives of philanthropy and for love of God. There are too many people in the world; that is the first article of faith of all those who, at present, in the name of the people, reign and govern. It is for this reason that they use their best efforts to diminish the population. Those who best acquit themselves of this duty, who practice with piety, courage, and fraternity the maxims of Malthus, are good citizens, religious men, those who protest against such conduct are anarchists, socialists, atheists.

That the Revolution of February was the result of this protest constitutes its inexpiable crime. Consequently, it shall be taught its business, this Revolution which promised that all should live. The original, indelible stain on the Republic is that the people have pronounced it anti-Malthusian. That is why the Republic is so especially obnoxious to those who were and would become again, the toadies and accomplices of kings—grand eaters of men, as Cato called them. They would make a monarchy of your Republic; they would devour its children.

There lies the whole secret of the sufferings, the agitations, and the contradictions of our country. The economists are the first among us, by an inconceivable blasphemy, to establish as a providential dogma the theory of Malthus. I do not reproach them; neither do I abuse them. On this point the economists act in good faith and from the best intentions in the world. They would ask nothing better than to make the human race happy; but they cannot conceive how, without some sort of an organization of homicide, a balance between population and production can exist.

Ask the Academy of Moral Sciences. One of its most honorable members, whose name I will not call, though he is proud of his opinions, as every honest man should be—being the prefect of I know not which department, saw fit one day, in a proclamation, to advise those within his province to have thenceforth fewer children by their wives. Great was the scandal among the priests and gossips, who looked upon this academic morality as the morality of swine! The savant of whom I speak was none the less, like all his fellows, a zealous defender of the family and of morality; but, he observed with Malthus, at the banquet of Nature there is not room for all.

M. Thiers, also a member of the Academy of Moral Sciences, lately told the committee on finance that, if he were minister, he would confine himself to courageously and stoically passing through the crisis, devoting himself to the expenses of his budget, enforcing a respect for order, and carefully guarding against every financial innovation, every socialistic idea—especially such as the right to labor, as well as every revolutionary expedient. And the whole committee applauded him. In giving this declaration of the celebrated historian and statesman, I have no desire to accuse his intentions. In the present state of the public mind, I should succeed only in serving the ambition of M. Thiers, if he has any left. What I wish to call attention to is that M. Thiers, in expressing himself in this wise, testified, perhaps unconsciously, to his faith in Malthus.

Mark this well, I pray you. There are two millions, four millions of men who will die of misery and hunger, if some means be not found of giving them work. This is a great misfortune, surely, and we are the first to lament it, the Malthusians tell you; but what is to be done? It is better that four millions of men should die than that privilege should be compromised; it is not the fault of capital, if labor is idle; at the banquet of credit there is not room for all.

They are courageous, they are stoical, these statesmen of the school of Malthus, when it is a matter of sacrificing laborers by millions. Thou hast killed the poor man, said the prophet Elias to the king of Israel, and then thou hast taken away his inheritance. Occidisti et possedisti. Today we must reverse the phrase, and say to those who possess and govern: You have the privilege of labor, the privilege of credit, the privilege of property, as M. Thouret says; and it is because you do not wish to be deprived of these privileges, that you shed the blood of the poor like wate: Possedisti et occidisti!

And the people, under the pressure of bayonets, are being eaten slowly; they die without a sigh or a murmur; the sacrifice is effected in silence. Courage, laborers! sustain each other: Providence will finally conquer fate. Courage! the condition of your fathers, the soldiers of the republic, at the sieges of Gênes and Mayence, was even worse than yours.

M. Léon Faucher, in contending that journals should be forced to furnish securities and in favoring the maintenance of taxes on the press, reasoned also after the manner of Malthus. The serious journal, said he, the journal that deserves consideration and esteem, is that which is established on a capital of from four to five hundred thousand francs. The journalist who has only his pen is like the workman who has only his arms. If he can find no market for his services or get no credit with which to carry on his enterprize, it is a sign that public opinion is against him; he has not the least right to address the country: at the banquet of public life there is not room for all.

Listen to Lacordaire, that light of the Church, that chosen vessel of Catholicism. He will tell you that socialism is antichrist. And why is socialism antichrist? Because socialism is the enemy of Malthus, whereas Catholicism, by a final transformation, has become Malthusian.

The gospel tells us, cries the priest, that there will always be poor people, Pauperes semper habebitis vobiscum; and that property, consequently, in so far as it is a privilege and makes poor people, is sacred. Poverty is necessary to the exercise of evangelical piety; at the banquet of this world here below there cannot be room for all.

He feigns ignorance, the infidel, of the fact that poverty in Biblical language, signified every sort of affliction and pain, not hard times and the condition of the proletaire. And how could he who went up and down Judæa crying, Woe to the rich! be understood differently? In the thought of Jesus Christ, woe to the rich meant woe to the Malthusians. If Christ were living today, he would say to Lacordaire and his companions: ” You are of the race of those who, in all ages, have shed the blood of the just, from Abel unto Zacharias. Your law is not my law; your God is not my God!

And the Lacordaires would crucify Christ as a seditious person and an atheist.

Almost the whole of journalism is infected with the same ideas. Let Le National, for example, tell us whether it has not always believed, whether it does not still believe, that pauperism is a permanent element of civilization; that the enslavement of one portion of humanity is necessary to the glory of another; that those who maintain the contrary are dangerous dreamers who deserve to be shot; that such is the basis of the State. For, if this is not the secret thought of Le National, if Le National sincerely and resolutely desires the emancipation of laborers, why these anathemas against, why this anger with, the genuine socialists—those who, for ten and twenty years, have demanded this emancipation?

Further, let the Bohemians of literature, today the myrmidons of journalism, paid slanderers, courtiers of the privileged classes, eulogists of all the vices, parasites living upon other parasites, who prate so much of God only to dissemble their materialism, of the family only to conceal their adulteries, and whom we shall see, out of disgust for marriage, caressing monkeys when Malthusian women fail—let these, I say, publish their economic creed, in order that the people may know them.

Faites des filles, nous les aimons—beget girls, we love them, sing these wretches, parodying the poet. But abstain from begetting boys; at the banquet of sensualism there is not room for all. The government was inspired by Malthus when, having a hundred thousand laborers at its disposal, to whom it gave gratuitous support, it refused to employ them at useful labor, and when, after the civil war, it asked that a law be passed for their transportation. With the expenses of the pretended national workshops, with the costs of war, lawsuits, imprisonment, and transportation, it might have given the insurgents six months’ labor, and thus changed our whole economic system. But labor is a monopoly; the government does not wish revolutionary industry to compete with privileged industry; at the work-bench of the nation there is not room for all.

Large industrial establishments ruin small ones; that is the law of capital, that is Malthus.

Wholesale trade gradually swallows the retail; again Malthus.

Large estates encroach upon and consolidate the smallest possessions; still Malthus.

Soon one half of the people will say to the other:

The earth and its products are my property.

Industry and its products are my property.

Commerce and transportation are my property.

The State is my property.

You who possess neither reserve nor property, who hold no public offices and whose labor is useless to us, TAKE YOURSELVES AWAY! You have really no business on the earth; beneath the sunshine of the Republic there is not room for all.

Who will tell me that the right to labor and to live is not the whole of the Revolution?

Who will tell me that the principle of Malthus is not the whole of the counter-Revolution?

And it is for having published such things as these, for having exposed the evil boldly and sought the remedy in good faith, that speech has been forbidden me by the government, the government that represents the Revolution!

That is why I have been deluged with the slanders, treacheries, cowardice, hypocrisy, outrages, desertions, and failings of all those who hate or love the people! That is why I have been given over, for a whole month, to the mercy of the jackals of the press and the screech-owls of the platform! Never was a man, either in the past or in the present, the object of so much execration as I have become, for the simple reason that I wage war upon cannibals.

To slander one who could not reply was to shoot a prisoner. Malthusian carnivora, I discover you there! Go on, then; we have more than one account to settle yet. And, if calumny is not sufficient for you, use iron and lead. You may kill me; no one can avoid his fate, and I am at your discretion. But you shall not conquer me; you shall never persuade the people, while I live and hold a pen, that, with the exception of yourselves, there is one too many on the earth. I swear it before the people and in the name of the Republic!

Pierre-Joseph Proudhon (1809-1865).

This essay was published in 1848. It was translated into English by Benjamin R. Tucker and published in 1885.

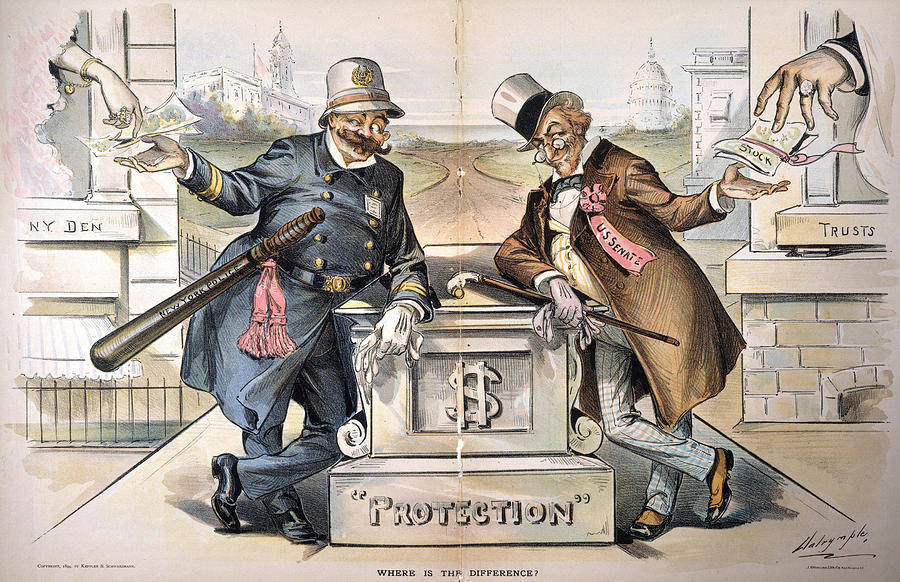

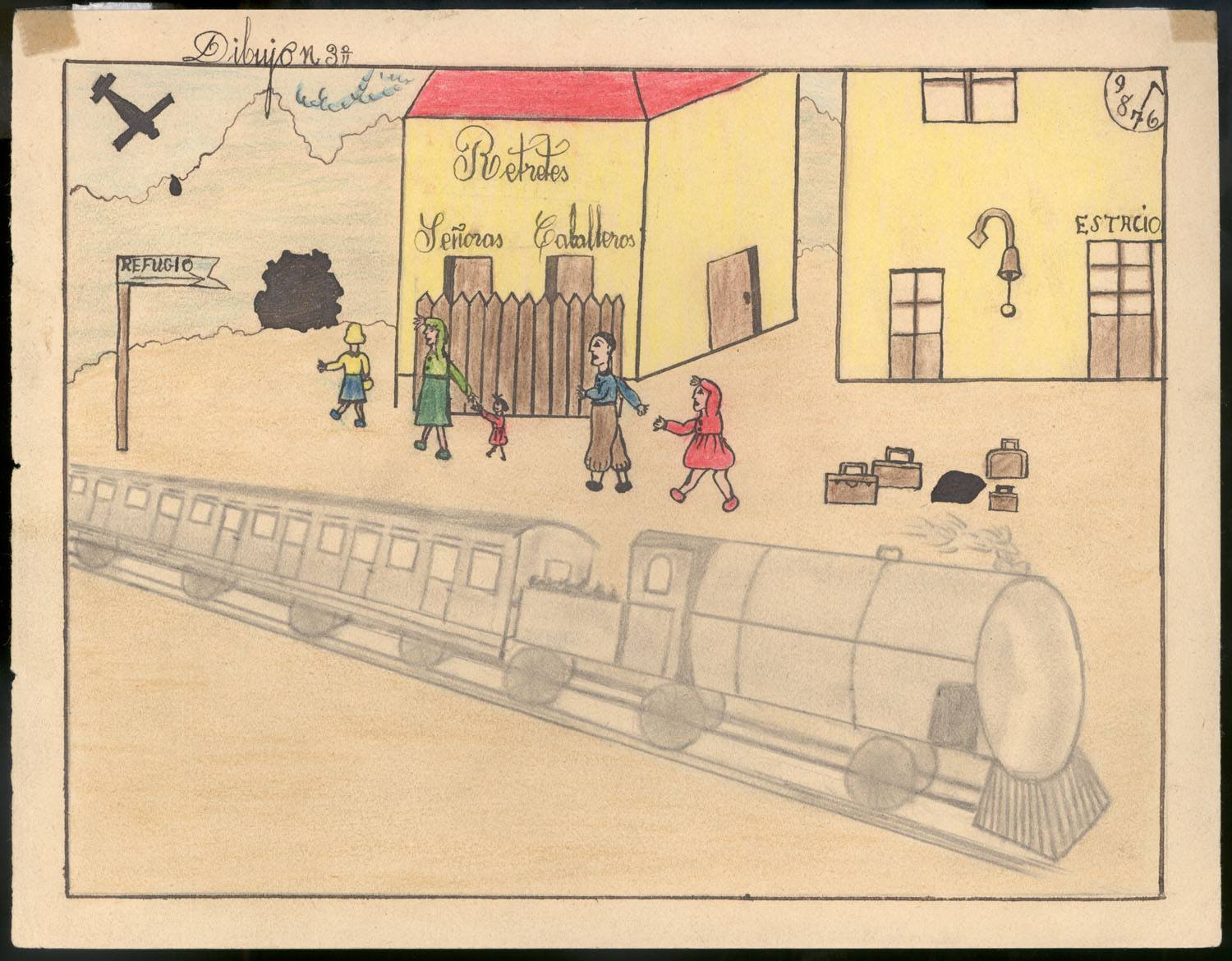

Featured: Illustration from the American School Board Journal, 1922.