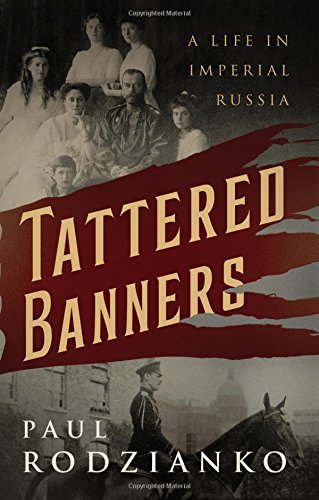

A marvellous and deeply evocative book has just been rescued from obscurity and given an afterlife. It is Tattered Banners by Paul Rodzianko. Until this reissue, by Paul Dry Books, this was a difficult book to find. The few copies of the first edition (published in 1939) that came on the market tended to be rather exorbitantly priced. Money-issues aside, this scarcity also meant that few had access to the important account given in this often moving memoir.

(published in 1939) that came on the market tended to be rather exorbitantly priced. Money-issues aside, this scarcity also meant that few had access to the important account given in this often moving memoir.

The structure of the narrative is a classic one – a man caught in the vortex of destruction. It is also the story of Russia – from the splendor of a sophisticated and cultured age, to the slaughter of the First World War, the cruelty of the Revolution in 1917, and the ensuing Civil War.

The book begins with descriptions of the frivolities, the preoccupations and even the innocence of that pre-war era: the follies and pranks of drunken officers, extravagant revels, glittering ballrooms, and even one or two pretty courtesans, like the blonde Nadejda (Nadezhda). A lost world, long vanished, and often forgotten: “a world that hate and passion have swept aside.”

It is worth noting that the book was written in English, a testimony to that lost cosmopolitan world when men and women were expected to know French, German, and English, along with Russian. Rodzianko knew all four languages. And his writing style is fresh, light and evocative, without being ponderous or preachy. And his insights are often startling, for their enduring relevance: “Then, as now, [people] think what their newspapers told them to think. Whatever they read most often in the biggest type is what nations believe. The masses become indignant, hysterical or conceited, according to the propaganda handed out to them.”

Rodzianko’s canvas is large on which the slow, inexorable passage into tragedy is depicted. The book opens with the terrible calamity of Khodynka Field (the stampede on Tsar Nicholas II’s coronation day, in which 1300 people were trampled to death). Thus, the reign of the last monarch of all the Russias began with a bloodbath – and his reign also ended with one.

Then follows the Russo-Japanese War (another disaster for Russia), the failed Revolution of 1905, which was a warm-up to the real one a dozen years later.

Rodzianko very fairly describes how Russia blundered and fumbled its way into the First World War, by siding with Britain and France, against Germany. It would be a war that everyone knew was of no benefit to Russia, but this was the age of alliances, or what we would call honor.

Russia knew little about modern warfare, and Rodzianko describes the ruinous mishaps, the bad judgment, terrible logistics (lack of food, ammunition, shells), with regiment after regiment wandering about here and there, not knowing whether to attack or retreat, with inept generals issuing orders that contradicted those given earlier.

The saddest parts of the book are the feats of grand heroism shown by the Russian rank-and-file which were nothing other than a terrible waste of life: “…the country they died for was soon to crash; their sacrifice was in vain.”

Then comes the “crash” itself – the Revolution, an unmitigated disaster for Russia, followed by the chaos of 1917, the slaughter of the royal family, and the ensuing long and bloody civil war.

The memoir now becomes a chronicle, and the chronicle becomes an eyewitness account to the terrible and bloody birth of the modern age. What begins as a time of enchantment, lurches into utter horror.

But more than anything else, the book is a life remembered, and the life belongs to Paul Rodzianko, soldier, professional equestrian, and member of the Russian nobility whose childhood of great wealth and privilege was spent playing in palaces, and visiting heroic men, like his grandfather, the old Prince Stroganoff, whose memory reached back to Napoleon and the conquest of Paris by the Russians.

There are cameo-appearances by Kaiser Wilhelm of Germany, who agrees to be tossed about by drunken cavalry officers; there is the kindly Tsar Nicholas, the holy man Rasputin and his murderer, Prince Youssoupoff, the great singer Chaliapin, the brave but doomed General Kolchak, and even a revolting lunch of plover eggs with King George V.

In recounting his life, Rodzianko meditates upon the loss of his world: “…the flower of Russia riding as they would ride to their deaths.”

Interestingly, this republication also marks the hundredth anniversary of the murder of Tsar Nicholas II and his entire family (July 17, 1918).

Rodzianko was with the Whites (the anti-Red faction in the Russian Civil War), when they captured Ekaterinburg, where the royal family was being held captive. The Whites had hoped to free the Tsar. But the Bolsheviks were far cleverer, and had shot them all and carefully hid the bodies, which were not found until 1998 (they had been located in 1979).

Rodzianko meticulously describes the grisly week he spent, piecing together what he could, trying to locate the bodies of the Tsar and his family. He fails, for the Reds are too meticulous in their murder. What he discovers instead is the vast inhumanity that was the Civil War, for Ekaterinburg and its environs are thickly scattered with graves of hundreds, if not thousands, shot by the Reds – a harbinger of what lay in store for Russia under Stalin.

He digs up bodies that he is told might belong to the royals, but he finds nothing conclusive. But he does manage to find a survivor – the little dog that belonged to Alexei, the young tsarevitch. Perhaps as a consolation, Rodzianko adopts the lost dog, from a lost time, and eventually brings him back to England. The dog’s name, sadly enough, was Joy.

This book is an enthralling read and should be on the bookshelves of all who like to wander in lost realms and muse awhile on days long gone. It is a book filled with atmosphere, color and lively anecdote. The only regret is that Rodzainko should have written more about his life, for as he observes: “I myself cannot believe that I have lived through and witnessed such things.”

The photo shows a work by Vladimir Pervuninsky.