As we know, history is one of the oldest sciences in the world. But the benefits of it are far from obvious and have been constantly questioned over the centuries. How was the question of the purpose of writing history, and the tasks of a historian, answered in the past?

Moses, who began compiling sacred history, did not use the concept of “history” itself – there was no need for it. For Moses, the story of creation, humanity, and the people of Israel was not some useful knowledge, but a proclamation to Israel of Israel’s purpose. God, leading the people out of Egypt, gives history to man as a vow of salvation.

Nevertheless, the emergence of history as scientific knowledge is usually associated with ancient tradition, and Herodotus is traditionally considered the first historian (5th century BC). Herodotus saw himself as a collector of “information” about “great and surprisingly worthy deeds” so that they “over time would not go into oblivion.” Herodotus (in his work The Histories, although this name is most likely later, for earlier the work was called The Muses) for the first time appears as an “historian” – an observer and narrator about the events that took place. The goal is not soteriological, but antiquarian.

But it is Thucydides (5th century BC) who introduces a more “scientific” task – he is engaged in “investigation.” In his Peloponnesian War he writes: “As for the events of this war, I set myself the task of describing them, receiving information not by questioning the first person I met and not at my personal discretion, but to depict, on the one hand, only those events, at which I myself happened to be present, and on the other – to analyze the messages of others with all possible accuracy. A thorough verification of the information was not easy, because the witnesses of individual events gave different coverage of the same facts, depending on their location to one of the warring parties or the strength of memory. My research, in the absence of everything fabulous in it, may seem unattractive. But if anyone wants to investigate the reliability of the past and the possibility of future events (which may someday be repeated by the property of human nature in the same or similar form), then it will be enough for me if he considers my research useful. My work was created as an eternal property, and not for momentary success with listeners.”

In other words, the benefits of history are pragmatic, avoiding mistakes in the future. It is also worth making a reservation here: history for ancient and later authors is not some kind of historical process, but a text, a story about events. Later, ancient authors were engaged in similar “investigations” (collection and analysis of information). For example, Aristotle (4th century BC) wrote The History of Animals, which became the basis for the creation of philosophical works on fauna: On the Parts of Animals, and On the Generation of Animals.

A step forward was made by the historian Polybius (2nd century BC), the author of The Histories. He believed that “knowledge of the past, rather than any other knowledge, can benefit people,” since “lessons learned from history most likely lead to enlightenment and prepare for engaging in public affairs,” and “the story of the trials of other people is the most intelligible, or the only mentor teaching us to courageously endure the vicissitudes of fate.”

It was Polybius who spoke about the “lessons of history,” which for him had a universal meaning and concerned every person. In addition, “diligent study of history, enriching us with this kind of experience, can beautify our leisure and provide us with entertainment.” Polybius thus not only raised history to the pedestal of human knowledge, but also gave it moral and entertainment value. The famous phrase of Cicero “history is the teacher of life” was already a repetition of Polybius’s thought. Subsequent ancient historians in different ways repeated what Polybius, Herodotus, and Thucydides said.

The first Christian historians interpreted their writings in an ancient context. Eusebius (4th century AD) wrote about “instructive lessons of history.” However, Sozomen (1st half of the 5th century AD) posed a more significant task: “Since for the reliability of history one must take special care of the truth, it seemed to me necessary to investigate these written monuments as much as possible… The narrator, as has been said, should do everything to serve the truth.” It is important to take into account that in Sozomen’s view truth was of divine origin, and history itself, in his words, is “not a human matter.”

Thus, already early Church historians were gradually beginning to bring their tasks closer to those that were characteristic of Moses. These principles were most clearly formulated by the blessed Theodoret of Cyrus (5th century): “Painters, depicting ancient events on panels and walls, of course, give pleasure to the viewers about what happened long ago; they keep that happening fresh in memory for a long time. But historians, instead of panels used books, and instead of paints – use the color of words, to make the memory of the past even stronger and firmer, because the painter’s art is worn down by time. Therefore, everything that has not yet been included in the history of the Church, I will try to describe: for indifference to the glory of famous deeds and oblivion of the most useful legends, I consider criminal.” He considered writing history to be a spiritual duty and a heroic deed.

The Christian West right up to the Renaissance retained the ancient understanding of history. However, from the end of the 17th century, with the emergence of science in Europe in the modern sense, an idea of the world historical process was formulated, which had its own clear and invariable laws.

Thus, there were the French Catholic Bishop Bossuet (Discourse on Universal History, 1681) and the Italian scientist Vico (Principles of a New Science Concerning the Nature of Nations, 1725) for whom the laws of history were a divine institution, like the laws of nature, and were associated with ethical norms. One way or another, for the first time, it became possible to talk about the “meaning of history,” with attempts to deduce it in the manner of a mathematical formula. Now history had begun to be understood rationally – and man became its hostage, a cog in a grandiose mechanism.

The Age of Enlightenment made its own adjustments here: it began to look at history as a self-developing process. Agnostic Lessing (The Education of the Human Race, 1780) spoke of historical progress and stages of religious and social development (by which he understood paganism, Judaism and Christianity).

Thus, history became an all-embracing process in which all of humanity participates, said the pantheist Herder (Reflections on the Philosophy of the History of Mankind, 1784-1791). The Napoleonic Wars that followed seemed to confirm this thesis.

Another inevitable conclusion from this idea was the thought of the pantheist Condorcet (Sketch for an Historical Picture of the Advances of the Human Mind, 1794): “If a person can, with almost complete certainty, predict the phenomena whose laws he knows, if even when they are unknown to him, he can, on the basis of past experience, predict, with a high probability, future events. Then why consider the desire to draw, with some plausibility. a picture of the future fate of the human race, based on the results of its history, as a chimerical enterprise?”

Historical science was already beginning to turn into an ideology and predict a happy future. True, Condorcet himself was sitting in a Jacobin prison, while he was writing his work, waiting for the guillotine.

After Hegel, who most clearly formulated the idea of a single historical process, the “philosophy of history,” which became the foundation of political ideology, blossomed in magnificent color. It was understood both in the materialistic “formational” aspect (Marx, Braudel) and in the idealistic “civilizational” one (Danilevsky, Spengler, Toynbee). More often, the first model was adopted by the Left (socialists and liberals), and the second – by the Right.

Later, the liberal “anti-philosophy” of history (Popper) was formulated, which generally denied any meaning in history and placed technical progress at the forefront. The circle of development of European thought was closed, and man was completely lost in the heap of “laws” and the whirlwind of “processes.” Historians, inspired by philosophers, and then experiencing some disappointment from the abundance of groundless schemes, went into “pure science” – into the study of small plots (so-called microhistory) or individual texts (postmodernism).

Perhaps the most profound criticism of the “philosophy of history” belongs to the outstanding theologian of the twentieth century, Archpriest Georges Florovsky. It was the identification of history with nature, in his opinion, that became the starting point of European utopianism.

Father Georges fundamentally opposed the idea of historical progress and human responsibility for history, a certain faceless “cosmic process” and personal “moral creativity.” Instead, history is to be understood as “the mystery of salvation and the tragedy of sin.” It has no other meaning. The historian is complicit in this dilemma because his work should be evidence of it. Proclaiming a “return to the fathers” in theology, Father Georges was faithful to them in his understanding of history and the tasks of a historian.

Following Moses, theologians of the 5th and 20th centuries spoke of history as an event centered on the communication of God and man, feat and salvation. Thus, human history rises above the laws of nature, goes beyond its inherent cyclicality and strict subordination to circumstances, gives each human action the status of unique and unconditionally significance. “If you are led by the spirit, you are not under the law” (Gal. 5:18). In this understanding, human history cannot be calculated, put into a mathematical formula, but only in this understanding does it acquire its true soteriological meaning.

Fedor Gaida is Associate Professor in the Faculty of History, Lomonosov Moscow State University. His research interests include, the political history of Russia at the beginning of the 20th century; Russian liberalism; power and society in a revolutionary era; Church and Revolution.

The Russian version of this article appeared in Provoslavie.

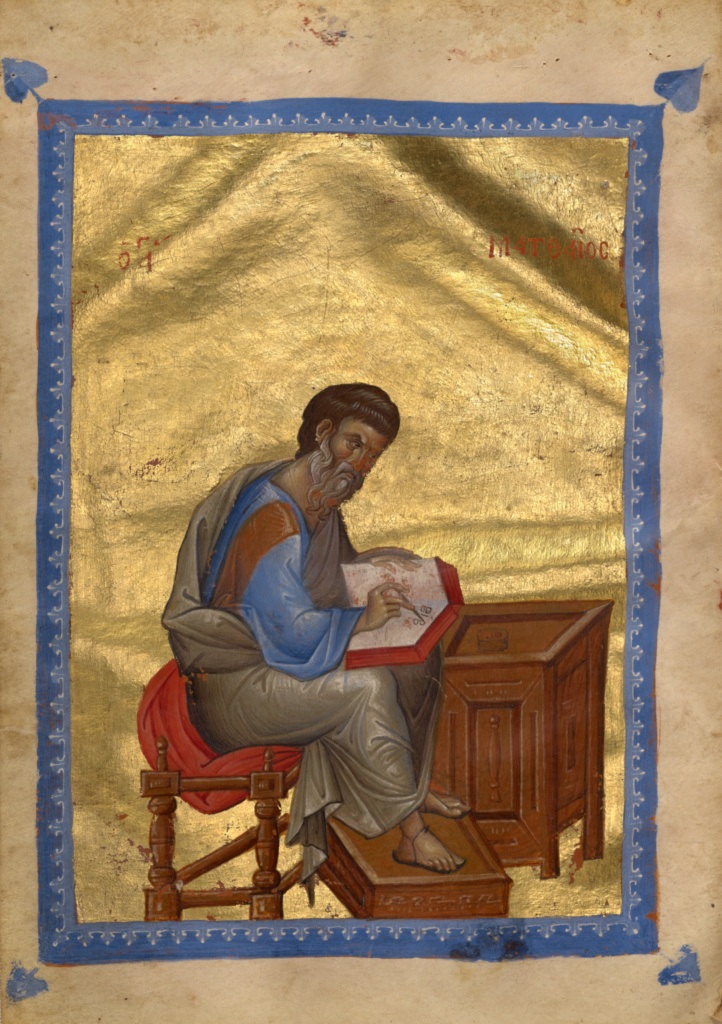

The image shows “Saint Matthew,” 13th-century Byzantine manuscript illumination.