Life, especially in the West, is gradually moving towards the fact that the diverse minorities, taken together, will become a solid and constantly growing majority. But Russia is no exception here. Perhaps this will be the ultimate embodiment of democracy.

In this regard, I recall an advertising slogan from the Moscow metro with a reference to Aristotle: “The city is the unity of the dissimilar.” However, questions immediately arise: where is the measure of this dissimilarity? Or is it immeasurable? And, perhaps, the most important question – is such dissimilarity an end in itself? Is it possible here to recall the “blossoming complexity” of Konstantin Leontiev and rejoice? How blooming is it? Aroma is not yet a sign of a blooming state.

Subculture is not a hobby club or a circle of young pioneers. The fundamental difference is that the values of a subculture are basic for its adherent, more important than all those that are shared by the rest of the surrounding world. A subculture can form naturally – on ethnic, geographic or traditional, religious grounds. However, this is not always the case: a subculture can arise artificially – by way of certain age, carnal, intellectual or “spiritual” interests. These, in fact, have nothing to do with subcultures of the first type; their nature is different, and they arise by the free will and choice of the person himself. This is how sects, gay communities, “hangouts,” and youth subcultures arise. And a person does not come here for an hour – you need to connect your life with the subculture, live by its interests and rules, soak yourself in its spirit. You will have to look at the outside world and at yourself through the eyes of the subculture.

The subculture does not seek to expand its ranks too actively, despite the oft-proclaimed formal slogans to the contrary. It is always characterized by the idea of its own exclusivity, sometimes elitism.

Youth subcultures for Russia are a recent phenomenon. In traditional society, they were none, because there was no “youth” in our understanding. A child – a boy or a girl – immediately grew into an adult with all his duties and behaviors. Usually this was associated with marriage, the time for which in Russia, as in other traditional societies, came with puberty. A woman a little over 30 years old was often already a grandmother and nursed her grandchildren, and her husband (or father-in-law) was in charge of a large family, consisting of several generations of relatives. A 15-year-old boy was getting ready for military service – this is how childhood ended.

Such a society, with its values of conservatism, was extremely mobile – each of its members played an important social role. Moreover, there was no need for some deliberately invented “state ideology” or “national idea” – a sense of responsibility was instilled from the cradle, and it almost always guaranteed against unpatriotic or selfish behavior. “Take care of honor from a young age,” an old Russian proverb said.

Released in 1762 from compulsory service, the nobles, quickly imbued with a sense of their own exclusiveness, nevertheless, did not form subcultures. The estate system generally excluded subcultures: it was built on the subordination of all groups of the population. In Russia, this was also coupled with a pronounced state paternalism.

In addition, the subculture is a predominantly urban phenomenon, while Russia as a whole remained an agrarian society. The farmers were quite divided among themselves. The urban noble society was too much tied to state interests. The public opinion of the nobility was based on ideas embedded in an all-Russian metric – the fate of the country, according to their own ideas, was in their hands and was directly decided by the “first nobleman” – the autocrat.

At the beginning of the 19th century, the young nobility adopted English dandyism, but this can hardly be called a subculture; there were only a few young dandies in the capitals. Pyotr Chaadayev, who became the embodiment of this phenomenon, was an exceptional and unique person. The hero of Pushkin’s novel, Eugene Onegin, is only “dressed like a dandy in London.” There was only the imitation of the Western model.

The disintegration of traditional social relations always gives rise to informal associations. They often have an age-related feature. In Russia, perhaps, the student community could be called the first “youth subculture.” Its final guise took place in the second half of the 19th century. It was not a clearly defined class; the authorities were not able to regulate its life by law; the values of the students were informal.

For these students, it was necessary to be different from everything around – which was deemed “gray and dull.” And the acquired scientific knowledge suggested that the way out lay in a new social reality, in the kingdom of total justice. Radical ideological features were combined with external differences. A real student even in that uniformed era was noticeable by external signs – an emphasized and deliberately provocative neglect of appearance. The student’s uniform, introduced in the 1880s, did not change the attitude of the student: the top buttons were not buttoned, the cap was always worn on one side, and an unkempt lock of hair emerged from under it. Real adherents of the student subculture turned into “eternal students,” their age ceased to matter.

The common people did not like “scubents” and treated them with suspicion. The student “going to the people” ended in complete failure. For example, in 1878, a no less famous and very revealing event took place, typical of that time: students of the Moscow University were beaten by meat merchants for revolutionary propaganda. A rumor spread that the young “gentlemen” had decided to call on the people to restore serfdom – and the butchers would not stand for it. It did not even occur to these butchers that agitation against the monarchy, which liberated the peasants, could have any other grounds, and that the “white collars” could oppose the wealthy strata of society.

Subculture always runs the risk of being misunderstood from the outside. The student subculture disintegrated at the beginning of the 20th century, as its values became widely spread in society. Against this background, the student lost his brightness and originality. And as the dream of social justice began to be actively realized, there were only few of the dreamers who did not drown in the bloody floods accompanying this embodiment.

The basis of any subculture is always utopia – the idea of the possibilities of a certain group of people to unite and jointly turn the world around. It can be a world revolution and a world commune, a technocratic future, or the victory of the national team in the world championship. The question is only in the scale of consciousness; and, as is obvious, that can be expanded in various ways. This is an extremely important task for subcultures.

Students of the 19th century read the latest books, prepared notes and discussed them in meetings, with the aim of immediately introducing the ideas they had read into their daily life. Propaganda or bomb – all a matter of taste and available skills. A century later, it became customary to compose acute social poems or philosophical parables and put them to music. In-between this noble occupation was the taking of certain drugs to stimulate creativity. Sometimes these drugs turned out to be too strong. What was the end result? Charm always ends in disappointment. It is good if, having entered a dead end, a person has the opportunity to get out of it. But what if there is no more time left?

As the horizons become smaller, the goals of subcultures also become smaller. Relaxation gradually becomes the main reference point. But it is dangerous for consciousness to exist in a state of “eternal relaxation” – this leads to its submission and destruction. If you don’t make an effort on yourself, there will always be someone else to do it for you; and he will make the choice for you. Maybe this is not bad? Over time, when a person ceases to be aware of himself, he will express just such a question. And this means that he has already lost himself and everyone who needs his help – along with the opportunity to receive it, such as, the country and its citizen.

And you can spend years or, if you are particularly lucky, decades in self-indulgence – exquisite and not very, “kind and naïve” or aggressive and misanthropic, highly ideal or “pop.” The world will not turn upside down because of all this – only the person himself will turn upside down. His personality will gradually wear out, burn out. An illusory unity with like-minded people will collapse. Others will lose interest; loneliness will be the result. Worst of all, it will acquire a universal character. Who should I call? “My soul, my soul, arise, why do you slumber?…”

Adolescence protracted to old age cannot evoke any other feeling than regret for the missed opportunities of the person himself and his neighbors. It is difficult now to judge what the future holds for Russia. Predictions in this matter are a completely ungrateful thing. One thing is clear – with the dictates of subcultures, there will be no such future at all.

Fedor Gaida is Associate Professor in the Faculty of History, Lomonosov Moscow State University. His research interests include, the political history of Russia at the beginning of the 20th century; Russian liberalism; power and society in a revolutionary era; Church and Revolution.

The Russian version of this article appeared in Provoslavie.

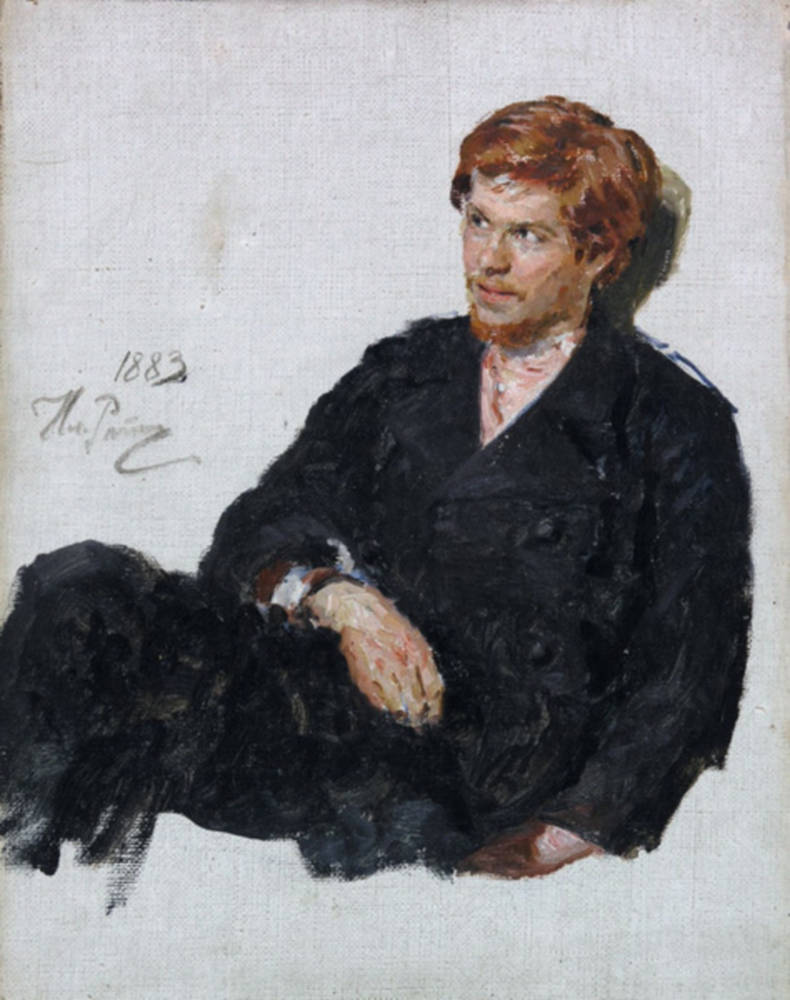

The featured image shows, “Student Nihilist,” by Ilya Repin, painted in 1883.