Reflections on the Divinity of Jesus, Formless Matter, and Conceptualization in the Human.

Here, I will endeavor to try to grasp the way in which the symbol of light is deployed on several levels of meaning, which are themselves linked to correspondent levels in the architecture of reality. Namely: those levels of meaning that are God considered in His ideality, God considered in His relationship to contra-material nothingness, God considered in His incarnation into the universe, and the consciousness of God considered in its incarnation into the consciousness of Jesus. On that basis, I will endeavor to overcome those three philosophical cleavages that are the opposition between radical Arians and the Trinitarians on the issue of whether Jesus is divine; the opposition between Gersonides and saint Thomas Aquinas on the issue of whether there was formless matter instead of a temporal beginning of matter; and the opposition between Averroes and saint Thomas Aquinas on the issue of whether the mind of God (rather than the human mind) is what conceptualizes in the human mind.

I understand God, let us recall, as follows: an infinite, eternal, substantial, volitional, and conscious field of singular ideational models which is completely incarnated into the universe while remaining completely external to the universe, completely ideational, and completely subject to a vertical (rather than horizontal) time; and which is not only completely sheltered from any forced effect (whether ideational or material) with one or more efficient causes in its willingness, but which, besides, is traversed, animated, efficiently-caused, and unified by a sorting, actualizing pulse which stands both as the active part of God’s will and as the apparatus, the Logos, through which God incarnates Himself while remaining distinct from His incarnation.

Considering some entity from the angle of one of its (present at some point) properties consists of considering how the property in question is inscribed within the whole of the entity’s (present at that point) properties. Considering some entity independently of one of its (present at some point) properties consists of considering what are the other (present at that point) properties in the entity when the property in question is ignored. In the majority of ideational entities and of material ones, the fact of ignoring some property lets all the other properties apply. In the case of that material entity that is the universe, some of its properties present at some point apply depending on whether the universe is considered from the angle (or instead independently) of that substantial relational property that is the incarnation relationship of the universe with respect to God.

Neantial, Ideational, and Material Conceptual Objects

A concept is a unit of meaning: it signifies a certain object taken from the angle of its constitutive properties (rather than from the angle of all of its properties). The properties (including constitutive) of a conceptual object coincide with the properties (including constitutive) that are imputed to the concerned conceptual object depending on whether material or ideational reality validates the imputation of the imputed properties. In a material or ideational conceptual object, its existential properties of (i.e., those of its properties that are relating to whether the object exists, and to how it exists or inexists) rank among the constitutive properties of the conceptual object in question. A neantial conceptual object is a conceptual object that contains no existential properties; just as every neantial conceptual object is contra-material or contra-ideational, no neantial conceptual object is material nor is it ideational.

Just as every conceptual object is material or ideational or neantial, every conceptual object is fictitious (in a weak or strong mode) or matching (in a weak or strong mode). Just as a fictitious material conceptual object and a matching material conceptual object are respectively a material conceptual object which happens to not exist (in the material field) and a material conceptual object which happens to exist (in the material field), a fictitious ideational conceptual object and a matching ideational conceptual object are respectively an ideational conceptual object which happens to not exist (in the ideational field) and an ideational conceptual object which happens to exist (in the ideational field). Just as a fictitious neantial conceptual object and a matching neantial conceptual object are respectively a neantial conceptual object which is a type of nothingness having not actually preceded the universe and a neantial conceptual object which is a type of nothingness having actually preceded the universe, a contra-ideational neantial conceptual object and a neantial contra-material conceptual object are respectively a type of nothingness substituted for the field of the Idea and a type of nothingness substituted for the field of matter.

A concept and its linguistically accepted definition (i.e., its definition accepted in a certain language) are considered synonymous in the considered language; that synonymy, instead of being true or false independently of reality (whether ideational or material), is nevertheless true or false according to ideational reality (in the case of the ideational objects and of the contra-ideational neantial object), or according to material reality (in the case of the material objects and of the contra-material neantial object). Just as the ideational reality validates or invalidates the synonymy between an ideational object (for example, God) and its accepted definition depending on whether the ideational reality validates whether the constitutive properties (including existential) of the concerned ideational object are those alleged by the accepted definition, material reality validates or invalidates the synonymy between a material object (for example, Chi) and its accepted definition depending on whether material reality validates whether the constitutive properties (including existential) of the concerned material object are those alleged by the accepted definition. As for the neantial objects, material reality validates or invalidates the synonymy between a contra-material neantial object and its accepted definition depending on whether material reality validates whether the constitutive properties of the concerned conceptual object are those contained in the accepted definition; just as the ideational reality validates or invalidates the synonymy between a contra-ideational neantial object and its accepted definition depending on whether the ideational reality validates whether the constitutive properties of the concerned conceptual object are those contained in the accepted definition.

The object of the concept of light is a matching material conceptual object, i.e., a material conceptual object that happens to exist in the material field. The concept of light means light taken from the angle of its constitutive properties; the linguistically accepted definition of light, which evolves as language evolves, must be judged true or false in the light of material reality. The currently accepted definition of light is as follows: “electromagnetic radiation whose wavelength, between 400 and 780 nm, corresponds to the sensitivity zone of the human eye, between ultraviolet and infrared.” Our knowledge of reality remaining irremediably perfectible, that definition is subject to a hypothetical revision one day or another (under the hypothetical progress of physics on that level); we will start from that definition, which we know is “true” until further notice.

Light: Symbol of the Ideality of God

Every light has: its source (i.e., what it emanates from), and its object (i.e., what it illuminates). We cannot correctly grasp what the symbol of light refers to without focusing on that conceptual trio—luminaire (i.e., source of light), illuminated object, and light. The light of a candle manifests itself via the flame which envelops the wick, and via the wax which the light of the candle illuminates; however the light of the candle is not visible itself. More generally, light manifests itself without making itself visible: in other words, it manifests itself in a mode other than that which would consist for it of making itself visible. In order for light to manifest itself via its source, a necessary, sufficient condition is that light manifests itself via the illuminated object; it is by illuminating its object that light manifests itself via what it illuminates, but it is, besides, by manifesting itself via the illuminated object that light manifests that it emanates from a certain luminary (and manifests which is its luminary). In other words, just as it is by illuminating that object it illuminates that light manifests itself through the illuminated object, it is by illuminating that object that light manifests itself through the luminaire.

A symbol is a concept that allows one or more other concepts to be glimpsed while leaving them in obscurity; it is both an incomplete path towards those other concepts, and a completely hermetic enigma about them. Let us endeavor to see what the concept of light opens up to: to begin with, the ideality of God. Just as matter is that which exists in a consistent, firm mode, the Idea is that which exists in a mode devoid of the slightest consistency and firmness. Just as materiality is what a material entity is composed of, ideality is what an ideational entity is composed of. Reality is subdivided into a material field and an ideational field; the universe occupies (and summarizes) the material field, but God occupies (without summarizing) the ideational field. The supramundane field is to be not confused with the ideational field: the supramundane field, in that it encompasses everything that is beyond the world, encompasses the ideational field as well as the neantial field (i.e., the field of the nothingness prior to the temporal beginning of the material field).

Interstellar vacuum, energy, or thought are modes of matter: they are as consistent as is wood or fire, but consistent in a different way. Light is a certain mode of matter; but it is a mode of matter which is so “fine” in its consistency that it evokes the ideality of which God is made. Let us specify that the Idea (which Plato and Pythagoras deal with) must be distinguished from the idea: the Idea is that which exists in a mode devoid of the slightest consistency and firmness, but the idea is a material entity (in the case of an idea lodged in the mind of a material entity) or an ideational entity (in the case of an idea lodged in the mind of an ideational entity). God is an Idea; but the concept of God in the mind of a certain human is an idea lodged in the mind of said human. Let us also clarify that physics only deals with a certain mode of matter: namely that mode of matter which has mass and extent. Thought (which has neither mass nor extension), as well as the void (which has extension but is devoid of mass), are both excluded from the field of physics; they nonetheless remain modes of matter. Light, although it falls within that mode of matter which occupies physics, evokes a mode of being which is beyond physics; although light is material, it evokes a mode of being that is truly immaterial.

Light: Symbol of God Considered in His Relationship to Contra-Material Nothingness

The light which crosses the void where the celestial bodies “float” barely manifests itself because it barely illuminates the celestial bodies; in other words, the void is black because the light emanating from the stars barely illuminates the celestial bodies. In that regard, light is a symbol of God considered in His relationship to contra-material nothingness. Namely that God—just as starlight barely illuminates the black of the interstellar void that it travels through—does not dissipate at all the contra-material nothingness that it overhangs.

Every conceptual object is either supramundane or intramundane. Just as every supramundane object is ideational or neantial, every intramundane object is material. Just as every conceptual object is intra-mundane or supramundane, every intra-mundane conceptual object is: either fictitious in a weak mode, or fictitious in a strong mode, or matching in a weak mode, or matching in a strong mode; the same is true of every supramundane conceptual object. A fictitious object in a weak mode is a fictitious object which could have been a matching object had this world been different or had another world existed; a fictitious object in a strong mode is a fictitious object which would have been fictitious even if this world had been different or if another world had existed. A matching object in a weak mode is a matching object which could have been a fictitious object had this world been different or had another world existed; a matching object in a strong mode is a matching object which would have been matching even if this world had been different or if another world had existed.

Every intra-mundane object matching in a strong mode is a material object; but a supramundane object matching in a strong mode is either ideational or neantial. Every matching intra-mundane object is a material object matching in a weak or strong mode; but a matching supramundane object is either an ideational object matching in a strong mode, or a neantial object matching in a strong mode. Every fictitious intramundane object is a fictitious material object in a weak or strong mode; but a fictitious supramundane object is either an ideational object fictitious in a strong mode, or a neantial object fictitious in a strong mode. A supramundane object of an ideational type is either matching in a strong mode, or fictitious in a strong mode; the same applies to every supramundane object of the neantial type. Every intramundane object (and, thus, every material object) is either matching in a strong mode, or matching in a weak mode, or fictitious in a strong mode, or fictitious in a weak mode.

Two modalities of the concept of nothingness are valid: a matching modality (in a strong mode) that is contra-material nothingness, i.e., that sort of nothingness that is substituted for the existence of matter; a fictitious modality (in a strong mode) that is contra-ideational nothingness, i.e., that sort of nothingness that is substituted for the existence of the Idea. Of those two modalities of the concept of nothingness, the former has as its object the contra-material nothingness (i.e., the absence of matter) which effectively preceded (chronologically) matter: at least, matter considered independently of the incarnation relationship of matter with regard to God. The latter modality has as its object contra-ideational nothingness (i.e., the absence of any ideational entity), which is fictitious. That the absence of matter was chronologically prior to matter (at least, matter considered independently of its relationship of incarnation with regard to God) is a fact which would have occurred even if our world had been different or if another world had existed; thus, contra-material nothingness is a modality of the concept of nothingness whose object is matching in a strong mode. God exists from all eternity (whether matter is considered from the angle of its incarnation relationship with regard to God), and His existence would be eternal even if our world were different or if another world had existed; contra-ideational nothingness is thus a modality of the concept of nothingness whose object is fictitious in a strong mode.

Matter, in that it had a temporal beginning (if we consider it independently of its relationship of incarnation with regard to God), was preceded by contra-material nothingness. By Himself, however, God cannot dissipate contra-material nothingness; no more than starlight can dissipate the black of the interstellar void. Precisely, the black of the interstellar void symbolizes contra-material nothingness. By itself, the ideality of which God is made cannot dispel that darkness; what is ideational cannot get substituted for the absence of what is material, no more than it can generate ideational effects substituted for the absence of what is material. The only way God can dispel that darkness, and introduce matter in place of darkness, is for Him to change Himself into what He is not: matter.

Light: Symbol of the Incarnation of God into the Universe

“In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God,” the Gospel of John tells us. The sorting, actualizing pulse which unifies, animates, and traverses the field of ideational essences present within God, and which operates the incarnation of God into the world (while allowing Him to remain external to the world which is His incarnation), is that “Word” whose mystery occupied the apostle John (or the Johannine community). It is inaccurate to say of God that He is His Word; the Word of God is nevertheless the active part of His will, as well as the apparatus of His incarnation. The Word, although it unfolds in a time that is eternal (i.e., which has neither beginning nor end) and vertical (i.e., where past, present, and future are simultaneous rather than successive), does unfold; in other words, the Word operating in the ideational field is gradual as is every speech formulated in the material field. Just as God creates (by incarnating Himself) in a gradual mode, the universe exists in a gradual mode; like a discourse that is being held, the universe is unfolding. That joint gradualness in the creation on the part of God, and in the existence of the universe, lets itself be glimpsed in these terms in the Koran: “And, with Our powers, We have built the sky, and assuredly, We continue to extend it.” For its part, the fact that God creates through His Word lets itself be glimpsed here as follows: “When He decides a thing, He simply says: “Be”, and it is immediately!”

What light is a symbol of is not only God considered from the angle of His ideality or of His relationship to contra-material nothingness; it is also God considered from the angle of His incarnation into the universe. Light, let us recall, does not manifest itself in the way that would consist for it of making itself visible. Instead of making itself visible, it manifests itself through its source (what illuminates), and its object (what is illuminated); and it is by illuminating its object that it manifests itself both through its object and its source. Let us see how the symbol of light illuminates the creation by God through incarnation. God is (symbolically) a light that stands out in three ways from the light of this world. In the first place, that light is its own source; it is both the lighting and the light that illuminates, the luminaire and what emanates from it. In the second place, that light that is God does not manifest itself by what it illuminates; God certainly enlightens the universe, but the universe does not manifest the presence of God who enlightens it. In the third place, the light that is God engenders what it illuminates; the light of God brings the world into being by illuminating it. To those three properties of light taken as a symbol of God incarnated into the universe correspond three properties of the incarnation of God into the universe. In the first place, God is substance, i.e., exists from all eternity and without having any efficient cause. In the second place, God remains external to the universe; that exteriority of God with respect to His own incarnation, that independence of God with respect to His own creation by incarnation, it follows from it that the universe does not manifest the presence of God. In the third place, God remains that which created (and is incarnated into) the universe; God is certainly external to His creation, the universe nonetheless remains what God created by means of His incarnation.

Light: SDymbol of the Incarnation of the Consciousness of God into the Consciousness of the Son of God

It is useful to remember that the light of God is ideational, whereas the light of our world is a modality of matter. God, who hardly manifests Himself through His creation by incarnation that is the universe, nevertheless inspired the words of the prophets; that inspiration, although it did not manifest God through the speech of the prophets, allowed the prophets to express themselves about God. God inspired what was said about Him; His inspiration, however, was not His manifestation. The Gospel according to John, however, says of God that while “no one has ever seen God [until then],” “the only Son, who is in the bosom of the Father, is the one who has made him known.” That inspired symbolic language can be deciphered in these terms: God, who until then had no more manifested Himself (were it partly) in His creation than His consciousness had been incarnated within the world, saw His consciousness become a human consciousness (i.e., the consciousness of the earthly soul of a certain human), but neither His consciousness nor anything of God manifested itself on that occasion.

Just as in any novel the plot can be considered from the angle of the creation relationship of the novel with regard to the novel’s author, or considered independently of said relationship of creation, a same statement with respect to a novel’s plot can be true or false depending on whether the novel is considered from the angle of the creation relationship of the novel with regard to the novel’s author, or considered independently of said relationship of creation. Let’s take a novel whose plot ends on a cliffhanger: in the novel considered from the angle of its relationship of creation with regard to its author, the plot ends on the cliffhanger in question; but, in the novel considered independently of its relationship of creation with regard to its author, the plot continues after the cliffhanger (instead of stopping at the end of the novel). The universe is a novel whose author is God, which He writes by means of his Word; but it is a novel whose words are incarnated into what they say (while remaining external to that material incarnation). Just as God’s words are those ideational essences that He selects and actualizes, the respective incarnation of God’s words is the respective incarnation of those ideational essences that He selects and actualizes. Jesus, in that he is the incarnation of the ideational essence of Jesus, is the incarnation of a certain part of God; but, in his consciousness, Jesus is also the incarnation of a certain (other) part of God in that the consciousness of God is incarnated into the consciousness of Jesus.

The consciousness of Jesus is symbolically a light, but it is a light that stands out in three ways from the non-symbolic light. In the first place, that light is its own object; it is both what illuminates and what is illuminated, the light and what the light illuminates. In the second place, the light that is the consciousness of Jesus illuminates its object while nevertheless leaving it in the shadows; that light illuminates itself without making itself visible. In the third place, the light that is the consciousness of Jesus does not manifest the source from which it emanates, no more than it manifests that it is an emanation. To those three properties of light taken as a symbol of the consciousness of Jesus correspond three properties of the consciousness of Jesus. In the first place, the consciousness of Jesus is at the same time the incarnated consciousness of God (regarding his consciousness in the universe considered from the angle of the relationship of incarnation of the universe with regard to God) and the consciousness of the soul nestled in the human Jesus; thus the consciousness of Jesus is both a property present in God (regarding the consciousness of Jesus in the universe considered from the angle of its relationship of incarnation with regard to God) and a property present in that non-divine entity that is the soul of the human Jesus. In the second place, the consciousness of Jesus, although it existed in the world, was no more manifested in the world than the consciousness present in some conscious material entity is in a position to manifest itself in the world; what is ideational and nevertheless in the world cannot manifest itself alongside any material entity. In the third place, the consciousness of God taken in its exteriority with regard to its own incarnation into the consciousness of the earthly soul of the human Jesus was not manifested in its incarnation; it was incarnated without that incarnation being manifestation.

Grasping what, of Jesus, is of God requires that we go beyond what John (or the Johannine community) seemed to understand from his own symbolic language when he expressed himself in these terms in his Gospel: “And the Word was made flesh, and dwelt among us, full of grace and truth; and we beheld his glory, the glory as of the only begotten of the Father.” What, of God, became flesh is not His word, but it is the respective ideational essence of those entities endowed with flesh (including the entity Jesus); what makes Jesus a Son of God is that are respectively incarnated a certain ideational essence into Jesus, and the consciousness of God into the consciousness of Jesus. The word of God is what operates the selection and actualization of some ideational essences; the ideational essence of Jesus, in witnessing its selection and actualization get carried out, witnesses Jesus come into the world with a substantial essence that includes the property (that is itself inscribed in the ideational essence of Jesus) of the incarnated consciousness of God. The universe is indistinct from God (although distinct from God who remains external to His own incarnation that the universe is); for his part, Jesus is indistinct from the ideational essence of Jesus and, thus, from a part of God (although distinct from his ideational essence which, while incarnated into Jesus, remains external to Jesus), but the consciousness of Jesus is indistinct from the (totality of the) consciousness of God (although distinct from the consciousness of God which, while incarnated into the consciousness of Jesus, remains external to the consciousness of Jesus).

Overcoming the Divide between Radical Arianism and the Trinitarian Doctrine

The entire universe, not just Jesus, is the incarnation of God; but, although God is entirely incarnated into the entire universe, the consciousness of God is only incarnated into the consciousness of one or more human individuals precisely elected so that their respective consciousnesses be the incarnated consciousness of God. The consciousness of God, while incarnating itself into one or more human consciousnesses, does not see the object of the consciousness of God incarnate itself into the object of those human consciousnesses in which the consciousness of God gets incarnated. The object of God’s consciousness is (at every point) one’s existence and the entire field of the ideational essences and the (simultaneous) past, present, and future of the operation of the sorting, actualizing pulse, as well as the entirety of the (successive) past, present, and future of the universe; but the object of the consciousness of the one or those in whom the consciousness of God is incarnated is (at every point) one’s existence and a certain part of the universe, and hypothetically (and in a mode which is, at best, approximative) a certain part of the field of the ideational essences. Only a handful of humans (rather than all or the majority of humans) or a single human (rather than several humans) sees the consciousness of God incarnate itself into theirs; Jesus was either the only human whose consciousness was the incarnated consciousness of God, or one of those few humans (through the ages) whose respective consciousness is the incarnated consciousness of God.

In the universe considered from the angle of its incarnation relationship with regard to God, the consciousness of Jesus is both the incarnated consciousness of God and the consciousness of the soul of Jesus; but, in the universe considered independently of its incarnation relationship with regard to God, the consciousness of Jesus is only the consciousness of the soul of Jesus. Likewise, in the universe considered from the angle of its incarnation relationship with regard to God, Jesus is at the same time a human endowed with a consciousness indistinct from the consciousness of God (in that his consciousness is the incarnated consciousness of God) and a human who in his consciousness has nothing divine nor anything of God; but, in the universe considered independently of its incarnation relationship with regard to God, Jesus is in his consciousness only human (instead of being endowed with a consciousness indistinct from the consciousness of God). In that the consciousness of God is co-eternal with God, the consciousness of Jesus is co-eternal with God in the universe taken from the angle of its relationship of incarnation with regard to God; but, just as much in the universe taken from the angle of its relationship of incarnation with regard to God as in the universe taken independently of said relationship of incarnation, Jesus (instead of being co-eternal with God) has a temporal beginning and end.

The soul, as I expressed myself on that subject in a previous writing, is an Idea which, like the ideational essence, is eternal although endowed with an efficient cause (through God); but which, unlike the ideational essence (which remains within God, and which sees God communicate to it His consciousness and will), is endowed with a consciousness distinct from the consciousness of God, and with an existence external to God. The soul retains its consciousness both when the soul is supramundane (i.e., located in the ideational field) and when it is earthly (i.e., located in a living entity within the material field); but, whereas the earthly soul is without any willingness and without any mind (although every terrestrial soul is nested in an entity that is, if not endowed with a mind, at least endowed with a willingness), the supramundane soul has a willingness and a mind respectively distinct from the willingness of God and from the mind of God. The (supramundane) soul rises to the rank of a god in the ideational field by having experienced, during its stay or stays (as an earthly soul) in the material field, a heroism that is sufficient in order for God to grant it a divine rank. Every divine soul is supramundane; but no earthly soul is divine, just as not every supramundane soul is divine. Although the soul of Jesus became divine at the end of the earthly stay it effectuated in the biological entity that Jesus is, the soul of Jesus had nothing divine during the stay in question.

Heroism and exploit, as I expressed myself on that subject in the same previous writing, must be taken respectively in the sense of the accomplishment (as a conscious material entity) of one or more exploits; and in the sense of an act that is jointly exceptionally creative (i.e., characterized by the mental creation of one or more exceptionally creative ideas), exceptionally successful (i.e., characterized by the complete achievement of an exceptionally difficult goal), and exceptionally endangering for one’s material subsistence. The (earthly) soul of Jesus rendered itself divine (on its return to the ideational field) by experiencing an earthly stay (as Jesus) which saw Jesus accomplish an exploit great enough for that stay to be sufficient to render divine the (supramundane) soul of Jesus. That exploit is that of having created a new, semi-worldly, and multi-millennial religion by dying on the cross. Each supramundane soul knows perfectly the content of each ideational essence; thus each supramundane soul pre-knows perfectly what its earthly stay will be when it opts for a certain earthly stay. God, although each supramundane soul makes use of a self-determined willingness in its decision to opt for some particular earthly stay rather than for another one, perfectly pre-knows the decision of each supramundane soul on that level. God, although He elected the (supramundane) soul of Jesus so that his (earthly) soul be the earthly soul (or one of the earthly souls) whose consciousness is the incarnated consciousness of God, saw the (supramundane) soul of Jesus make use of a self-determined willingness in its choice of an earthly stay characterized by the incarnation of the consciousness of God into the consciousness of the (earthly) soul.

God, while incarnating Himself in the world, remains external to the world which is His incarnation; but the world, for its part, remains indistinct (rather than distinct) from God whose incarnation it is. A same statement can nevertheless be true or false depending on whether we consider it in the world taken from the angle of its incarnation relationship with regard to God, or in the world considered independently of its incarnation relationship with regard to God. In the world taken from the angle of the incarnation relationship of the world with regard to God, Jesus is endowed with a consciousness that is both indistinct from the consciousness of God and distinct from the consciousness of God; but, in the world taken independently of the incarnation relationship of the world with regard to God, Jesus is endowed with a consciousness distinct from the consciousness of God (rather than indistinct from all or part of the consciousness of God). Accordingly, the overcoming of the cleavage between radical Arianism and the Trinitarian doctrine is constitutive of a correct answer to the question of the divinity of Jesus (i.e., the question of knowing whether Jesus is divine). Moderate Arianism considers Jesus as a human who, in that he is the incarnated Father, was both created by the Father and created as indistinct (though distinct) from the Father; and who, in that he has a temporal beginning and end, is not co-eternal with the Father whose incarnation he is. For its part, radical Arianism envisages Jesus as a human who has nothing divine and who, in that he was created by the Father in a mode other than a creation by incarnation, is human (rather than God) and distinct from the Father (rather than indistinct from the latter); and as a human who, in that he has a temporal beginning and end, is not co-eternal with the Father. Whereas, according to moderate Arianism, Jesus is (incarnated) God without being co-eternal with the Father, Jesus, according to radical Arianism, is neither God nor endowed with anything divine nor is he co-eternal with the Father (although he is created by the Father).

Intermediate positions are found between radical and moderate Arianisms; but all modalities of Arianism have in common that they are opposed to the Trinitarian doctrine, for which Jesus is both the incarnation of God (instead of being a creature without anything divine nor anything of God) and an entity co-eternal with God. Knowing which modality of Arianism was the one that Arius actually defended is a problem on which I will not take position here. The cleavage between radical Arianism and the Trinitarian doctrine sees my position on the question of the divinity of Jesus operate an overcoming in these terms. The entire universe (and not only Jesus within the universe) sees God incarnate Himself into it, what is beyond the understanding of the Trinitarian doctrine and of radical Arianism (as well as of all modalities of Arianism). The assertion (in the Trinitarian doctrine) that Jesus is both human and indistinct from God (rather than a part of God) is partially true in that, in the case of the world taken from the angle of its incarnation of God (rather than in the case of the world taken independently of its incarnation relationship with regard to God), Jesus is his incarnated ideational essence (and thus an incarnated part of God), and a human endowed, besides, with a consciousness which is both the consciousness of the (earthly) soul of Jesus and the incarnated consciousness of God. For its part, the assertion (in radical Arianism) that Jesus has nothing divine is partially true in that, in the case of the world taken independently of its incarnation relationship with regard to God, Jesus is a human who is no more an incarnated ideational essence than he is a human endowed with a consciousness indistinct from the consciousness of God.

In the case of the world taken from the angle of its incarnation relationship with regard to God, the consciousness of Jesus is co-eternal with the consciousness of God; but (whether the world is taken independently of its incarnation relationship with regard to God) Jesus himself does have a beginning and an end in (horizontal) time. As such, the assertion (in radical Arianism) that Jesus is not co-eternal with God is true; but the affirmation (in the Trinitarian doctrine) that Jesus is co-eternal with God retains a part of truth in that the consciousness of Jesus in the world taken from the angle of the incarnation relationship of the world with regard to God is indeed co-eternal with the consciousness of God.

Overcoming the Divide between Gersonides and Saint Thomas Aquinas

The question of formless matter (i.e., the question of whether the universe, instead of having known a temporal beginning from contra-material nothingness, experienced a formless matter that was without any temporal beginning) is another question which demands the overcoming of a certain philosophical cleavage: here, the cleavage between Gersonides and saint Thomas Aquinas. Whereas formless matter is matter that exists without entering into the composition of any material entity, arranged matter is matter that enters into the composition of a certain material entity (within which it coexists with formal properties). The Gersonidean position on the question of formless matter is that the universe, instead of having experienced a temporal beginning (from contra-material nothingness), experienced a formless matter (which had always been) from which God operated to create a universe which be endowed with form and not only matter; for its part, the Thomist position on the question of formless matter is that the universe, instead of having experienced a formless matter (without any temporal beginning), had a temporal beginning which saw the universe begin with an already arranged matter.

Each of those two positions has a part of truth (depending on whether the universe is considered independently of its relationship of incarnation with regard to God, or from the angle of said relationship), and a part of falsehood (depending on whether the universe is considered independently of its relationship of incarnation with regard to God, or from the angle of said relationship). The relationship of incarnation of the universe with regard to God is co-eternal with God; but the relation of incarnation of a given entity within the universe with regard to its own ideational essence is no more co-eternal with the ideational essence in question than a given entity within the universe (whether the latter is considered independently of the relationship of incarnation of the universe with regard to God or from the angle of said relationship of incarnation) is co-eternal with its own ideational essence. The universe is nevertheless co-eternal with God when it comes to the universe considered from the angle of its relationship of incarnation with regard to God; regarding the universe considered independently of said relationship of incarnation, the universe, instead of being co-eternal with God, is endowed with a temporal beginning. The universe considered from the angle of its relationship of incarnation with regard to God certainly saw arranged matter begin temporally; but, whereas the universe considered from the angle of its relationship of incarnation with regard to God sees the temporal beginning of arranged matter follow a phase (without any temporal beginning) of the universe that was characterized by formless matter, the universe considered independently of its relationship of incarnation with regard to God saw the universe begin temporally (from contra-material nothingness) and begin with an already arranged matter.

What renders partially true the Thomist affirmation of the temporal beginning of the universe (from contra-material nothingness) is that the universe considered independently of its relationship of incarnation with regard to God is (unlike the universe considered from the angle of said relationship of incarnation) effectively endowed with a temporal beginning. Likewise, what renders partly true the Gersonidean assertion that the universe, instead of having experienced a temporal beginning (from contra-material nothingness), experienced a formless matter is that the universe considered from the angle of its relationship of incarnation with regard to God has (unlike the universe considered independently of said relationship of incarnation) actually passed through the phase (without any temporal beginning) of a formless matter rather than through the phase of an arising from contra-material nothingness. Every entity (whether ideational or material) is a compound of form and composition: the universe considered from the angle of its relationship of incarnation with regard to God was therefore a semi-entity so long as the matter which composed it was a formless matter. For its part, the universe considered independently of its relationship of incarnation with regard to God was an entity as soon as its existence began temporally.

Overcoming the Divide between Averroes and Saint Thomas Aquinas

Conceptualization consists of producing a concept or a definition of said concept or a description of all or part of the object of said concept; conceiving a concept consists of conceptualizing, or judging that a concept or a certain definition of said concept or a certain description of all or part of the object of said concept are valid. The question of conceptualization in the mind of God (i.e., the question of whether it is the mind of God, not the human mind itself, which conceptualizes in the human mind) has been the subject of a cleavage between Averroes and saint Thomas Aquinas. Whereas the former conceives of the human mind as incapable of conceptualizing, and the mind of God as that mind which conceptualizes in the human mind, the latter conceives of the human mind as capable of conceptualizing (just like the mind of God), and the conceptualization in the human mind as the work of the human mind itself.

Every concept (i.e., every unit of meaning) is an idea; but every idea is either a concept or an association of concepts. Every definition is an association of concepts; but not every association of concepts is a definition. The willingness (i.e., the pursuit of one or more ends) is either acting (i.e., employing one or more means for the purpose of an end), or non-acting (i.e., pursuing an end without employing any means for the purpose of that end); in God, the sorting, actualizing pulse, the Word, is the acting willingness. An object of willingness (i.e., an end that a willingness pursues, or the means or the various means that it employs for the purpose of an end) is never an idea; in every conscious volitional entity, willingness (whether it is acting or non-acting) is nevertheless accompanied by the idea of the object of willingness. Just as a volitional idea is an idea that accompanies an object of willingness (without causing the object in question), an actional volitional idea and a non-actional volitional idea are respectively a volitional idea that accompanies an end or means present in an acting willingness; and a volitional idea which accompanies an end in a non-acting willingness. In God, the sorting, actualizing pulse, in that it merges with acting willingness, is distinct from volitional ideas; each operation of said pulse is nevertheless accompanied by a correspondent idea in the mind of God. Just as an actional volitional idea in God is a volitional idea which corresponds to a certain operation of the sorting, actualizing pulse, an actional volitional idea which, in God, corresponds to a means in acting willingness and a non-actional volitional idea which, in God, corresponds to an end in acting willingness are respectively a volitional idea which corresponds to a selection and actualization; and a volitional idea which corresponds to an incarnated ideational essence. From an ideational entity present in the material field, nothing can be the object of an experience by a material entity; but it is possible for a human material entity to have an experience (which nevertheless is, at best, approximative) of all or part of an ideational essence, as well as of the consciousness of God or of a supramundane soul, as well as of all or part of (what are at the moment of that experience) the non-actional volitional ideas in the mind of God, as well as of all or part of (what are at the moment of that experience) the ideas in the mind of a certain supramundane soul.

A non-actional volitional idea in God is an idea corresponding to an end which is certainly in the will of God, but which does not relate to the operations of the sorting, actualizing pulse. Just as an ideational essence present in God must be distinguished from that essence’s concept present in the mind of God, the direct grasping of an ideational essence in God must be distinguished from the direct grasping of an idea in the mind of God. In the mind of God, ideas that are other than non-actional volitional ideas are also those ideas that God does not allow humans to grasp; in the mind of God, non-actional volitional ideas are those ideas that God allows humans to grasp, but a grasp that is, at best, approximative and whose effectiveness varies from one individual to another. The mind of God, although capable of conceptualization, is no more the mind that conceptualizes in the human mind than humans are incapable of conceptualizing; the Thomist position that the human mind, like the mind of God, is itself a conceptualizing mind (instead of the mind of God being that mind which conceptualizes in the human mind) is true. The Averroist position that the human mind, although incapable of conceptualization, sees the mind of God conceptualize in it remains partially true: on the one hand, in that the human mind is capable of conceptualizing from a direct grasping of all or part of the non-actional volitional ideas in the mind of God, a grasp whose effectiveness is, at best, approximative and varies from one individual to another. On the other hand, in that the human mind is capable of conceptualizing from a direct grasp of all or part of the ideational essences contained in God, a grasp whose effectiveness is, at best, approximative and varies from one individual to another.

A non-actional volitional idea in God is an idea corresponding to an end which is certainly in the will of God, but which does not relate to the operations of the sorting, actualizing pulse. Just as an ideational essence present in God must be distinguished from that essence’s concept present in the mind of God, the direct grasping of an ideational essence in God must be distinguished from the direct grasping of an idea in the mind of God. In the mind of God, ideas that are other than non-actional volitional ideas are also those ideas that God does not allow humans to grasp; in the mind of God, non-actional volitional ideas are those ideas that God allows humans to grasp, but a grasp that is, at best, approximative and whose effectiveness varies from one individual to another. The mind of God, although capable of conceptualization, is no more the mind that conceptualizes in the human mind than humans are incapable of conceptualizing; the Thomist position that the human mind, like the mind of God, is itself a conceptualizing mind (instead of the mind of God being that mind which conceptualizes in the human mind) is true. The Averroist position that the human mind, although incapable of conceptualization, sees the mind of God conceptualize in it remains partially true: on the one hand, in that the human mind is capable of conceptualizing from a direct grasping of all or part of the non-actional volitional ideas in the mind of God, a grasp whose effectiveness is, at best, approximative and varies from one individual to another. On the other hand, in that the human mind is capable of conceptualizing from a direct grasp of all or part of the ideational essences contained in God, a grasp whose effectiveness is, at best, approximative and varies from one individual to another.

Conclusion

Genesis distinguishes between primordial light and the light of the sun and the moon; the primordial light was created before the first day, with “the heavens and the earth,” but the sun and the moon were created only on the fourth day. Genesis tells us of God that He creates by “speaking,” and that the primordial light is His creation. As God invites humans to complete His creation that is the universe, the word that He inspires invites humans to deepen the symbolism it contains. The primordial light, we think, is a symbol of God envisaged in that ideality that is evoked by the finesse of the mode of matter that is light; a symbol of God envisaged in His inability to replace contra-material nothingness so long as He is only a light in the darkness; a symbol of God envisaged in the fact that He incarnates Himself into the world as a light which would create, by illuminating it, the illuminated object itself; and a symbol of God envisaged in the fact that His consciousness, while seeing itself incarnated in the consciousness of Jesus, remained hidden in that incarnation like a luminaire that its light would not manifest.

The “beginning” with which Genesis and the Gospel according to saint John open is no chronological beginning, but a pre-chronological one. In other words, the time of origins, instead of being the beginning of the time of this world, is that time without beginning and without succession from which the beginning of the succession of time in this world stems. Saint John, who symbolically identifies “the Word” to “the true light, which, when coming into the world, enlightens every man,” adds that this light “was in the world, and the world was made by it, and the world did not know it.” The deciphering of those inspired symbolic words involves the overcoming of these three ancient philosophical cleavages: the cleavage between radical Arians (for whom Jesus is a creature with a temporal beginning and end, and a creature who is God-created without being incarnated God) and Trinitarians (for whom Jesus is a creature co-eternal with God, and a creature who is incarnated God) on the question of the divinity of Jesus; the cleavage between Gersonides (for whom a formless matter without temporal beginning, not contra-material nothingness, was prior to the compound of form and matter in the universe) and saint Thomas Aquinas (for whom the universe had a beginning in time and began as a composite of form and matter) on the question of formless matter; and the cleavage between Averroes (for whom it is the spirit of God which conceptualizes in the human spirit) and saint Thomas Aquinas (for whom it is the human spirit which conceptualizes in the human spirit) on the question of conceptualization in the mind of God.

It is false that God is entirely incarnated into Jesus; it is no less false that there is nothing of God that is incarnated into Jesus. Jesus sees a part of God incarnate itself into Jesus, and an (other) part of God incarnate itself into a part of Jesus. What, of God, is incarnated into Jesus is a certain ideational essence; but what, of God, is incarnated into that part of Jesus that is the consciousness of Jesus is the consciousness of God. Jesus (whether the world is taken from the angle of its incarnation relationship with regard to God, or independently of said incarnation relationship) has a beginning and an end in time; but the consciousness of Jesus in the world considered from the angle of the incarnation relationship of the world with regard to God is indeed co-eternal with the consciousness of God.

The universe considered from the angle of the incarnation relationship of the universe with regard to God has experienced—instead of a temporal beginning which would have seen it begin with an already arranged matter—a formless matter which never began temporally, but from which God operated to create a universe which be veritably a composite of form and matter. Concerning the universe considered independently of the incarnation relationship of the universe with regard to God, the latter—instead of having passed through a formless matter whose phase would never have begun in time, but would have temporally preceded the phase of a universe composed of arranged matter—has effectively begun in time with an already arranged matter which temporally began from contra-material nothingness.

The human mind (rather than the mind of God) is what conceptualizes in the human mind; the human mind, with an efficiency which varies from one individual to another, and which is, at best, approximative, is nevertheless in a position to conceptualize from a direct experience of all or part of the ideational essences contained in God. Besides, the human mind, with an efficiency which varies from one individual to another, and which is, at best, approximative, is in a position to conceptualize from a direct experience of the consciousness of God and of all or part of the non-actional volitional ideas contained in the mind of God. Precisely, the mystical experience is the suprasensible experience a conscious material entity makes of the consciousness of an entity that is ideational (and present in the ideational field), or of one or more ideas contained in the mind of an entity that is ideational (and present in the ideational field). To humans, God allows the grasp (in a mode that is, at best, approximate) of all or part of His non-actional volitional ideas; of His mind, it prevents him from grasping (even in an approximate mode) the slightest idea other than a non-actional volitional idea.

The Word, which incarnated the consciousness of the ideational entity that is God into the consciousness of the soul of the human entity that is Jesus, made himself the object of the symbolic discourse inspired to Jesus; thus it can be said symbolically of the Word that he is “the true light, which, when coming into the world, enlightens every man.” Jesus saw his consciousness incarnate the consciousness of God in the world, and the (global) incarnation of God into the universe, while having formless matter precede the universe considered as incarnation, caused the beginning in horizontal time of the universe considered independently of that incarnation, and the consciousness of God, although it manifests itself in the mystical experience of the consciousness of God, was not manifested in its incarnation; thus it can be said symbolically of God that He is a light which “was in the world, and the world was made by it, and the world did not know it.” God, who no more manifests Himself in His incarnation into the world than He manifests Himself in the incarnation of His consciousness into the consciousness of (the earthly soul of) the human Jesus, manifests in suprasensible experience (which is carried out in a mode which is, at best, approximative) all or part of the ideational essences contained within Him, as well as all or part of the non-actional volitional ideas contained in His mind. Suprasensible experience—when it has as its object all or part of the field of the ideational essences in God, or all or part of the non-actional volitional ideas contained in His mind—is that through which God illuminates us; the grasp of what are (at a given moment) all or part of those non-actional volitional ideas present in the mind of God (at the concerned moment) is that by which God reveals to us the content (at the concerned moment) of that which is sometimes considered His heart.

The fact that a certain human entity, at a given moment, is grasping in an approximative mode all or part of what the non-actional volitional ideas are at the moment in the mind of God is inscribed in the ideational essence of the human entity in question, just as is inscribed in the ideational essence in question what are those non-actional volitional ideas present in the mind of God at the moment of the grasping. The same applies to a grasping whose effectiveness is less than approximative. God is not constrained by any actualized ideational essence to have some non-actional volitional ideas in mind at a given time; He nevertheless ensures in the operation of His Word that, when a certain actualized ideational essence states what all or part of His non-actional volitional ideas are at a given moment, what His non-actional volitional ideas are effectively at the moment in question validates what the ideational essence states about all or part of those ideas. Likewise, no supramundane soul is constrained by any actualized ideational essence to have some ideas in mind at any given moment; but God, in the operation of His Word, ensures that, when a certain actualized ideational essence declares what all or part of the ideas are at a given moment in a given supramundane soul, what the ideas are effectively in the soul in question at the moment in question validates what the ideational essence states about all or part of those ideas. If the parallel between what a certain actualized ideational essence states about a certain idea present in the mind of God at a given moment and the content of the mind of God at the moment in question were to fail, then the universe would not fail to implode and to experience a reset; the same is true of the parallel between what a certain actualized ideational essence states about a certain idea present in the mind of a certain supramundane soul at a given moment and the content of the concerned supramundane soul at the concerned moment. Although God makes Himself capable of errors in His quest to make the universe evolve towards ever-increasing order and complexity, He is (and forever remains) incapable of errors in His approach to ensuring that never any of those parallels fails.

Grégoire Canlorbe is an independent scholar, based in Paris. Besides conducting a series of academic interviews with social scientists, physicists, and cultural figures, he has authored a number of metapolitical and philosophical articles. He also worked on a (currently finalized) conversation book with the philosopher, Howard Bloom. See his website.

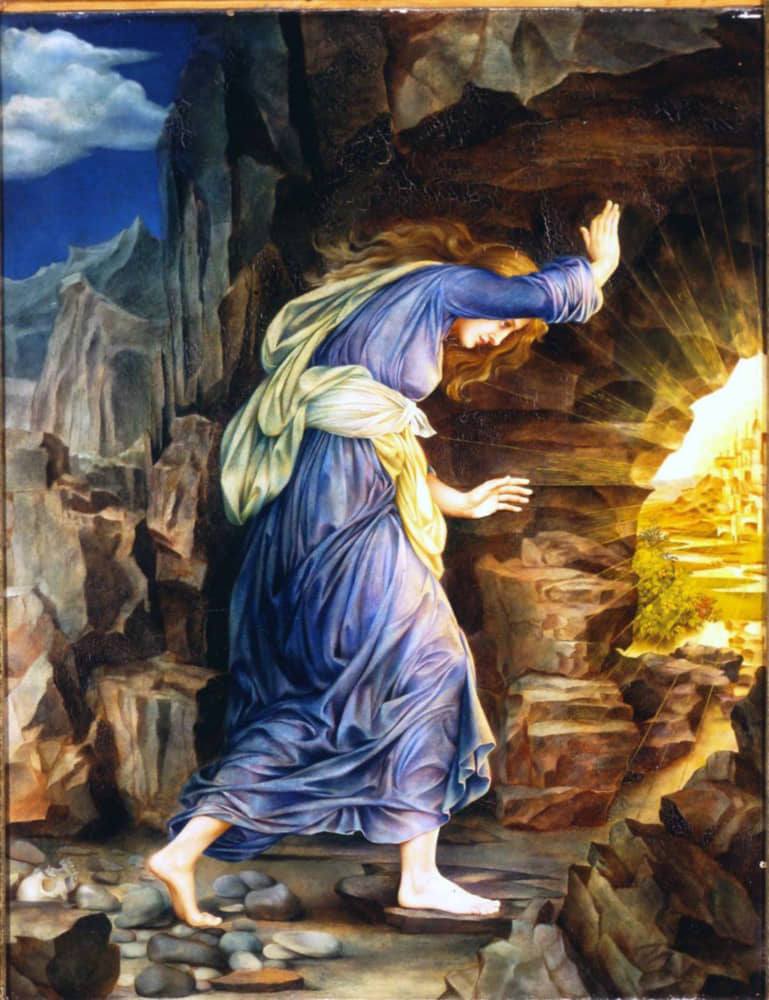

Featured: God separating the water from the land; engraving, Nazerene Brotherhood, 19th century; published in 1937.