Causality, Necessity And Permanence

Existence at some point in material entities is both endowed with an originated character (i.e., the character of finding its origin somewhere—whether the entity is created rather than uncreated); and with the character of being either permanent (i.e., doomed to continue) or provisory (i.e., doomed to end). Also, material entities (such as the human intellect represents them to itself in its impressions or in its conjectures, if not from sensible experience, at least from what it thinks to be sensible experience taken as such, i.e., naked, mere sensible experience) are engaged in causal relations; what is tantamount to saying that they’re endowed with causal relational properties. Though some men are able to have suprasensible access (to the ideational realm), their access is irremediably made, strictly, of “impressions” (i.e., illusions produced by suprasensible experience), which are approximately true at best.

As for the human intellect’s contact with sensible experience, it is (strictly) made of observations and of impressions (i.e., illusions produced by sensible experience, which look like sensible experience but are instead deformed echoes of what is actually observed). Yet Hume’s assertion, in essence, that the concept of (efficient) cause in the human intellect is the strict account of the impression of a sequence necessarily repeated identically that is only produced in it by the regular sensible experience of a chain repeating itself identically (under identical circumstances) is false on at least two levels.

On the one hand, that affirmation confuses the concept of (efficient) cause and the concept of an efficient cause whose effect is not only necessary at time t but necessarily identical to itself over the course of time. On the other hand, it is mistaken about the relation of the human intellect to sensible experience, which it wrongly conceives of as a strict relation of observation and impression by habit. One thing is to say that the impact of the ball with the pool cue is the efficient cause of the movement of the ball at time t, but another is to say that the impact in question necessarily causes the movement in question at the concerned time.

Yet another is to say that, if, in the future, the shock is repeated strictly identically under strictly identical circumstances, then the effect itself will necessarily repeat itself each time (and, each time, will necessarily repeat identically); regardless of the time the shock identically repeats under identical circumstances.

As for the relation of the ontological concepts of the human intellect (including the efficient cause—and the efficient cause jointly necessary and necessarily identical to itself under identical circumstances over time) to sensible experience, it is most likely that each ontological concept taken in isolation, whatever it may be, finds its complete origin, either in one or more human instincts, or in conjectures of the human intellect in contact with (naked) sensible experience, or in one or more sensible impressions (i.e., one or more impressions produced by the sensible experience on the human intellect), or in conjectures of the human intellect in contact with one or more sensible impressions, or in a legacy of the acquired culture, or in one or more suprasensible impressions, or in a mixture between all or part of those things.

Whatever its origin, the human intellect opts for trusting an ontological concept in its possession if (and only if) it judges the latter as being confirmed by the sensible (and hypothetically suprasensible) experience or judges it as being (highly) corroborated by the sensible (and hypothetically suprasensible) experience or judges it as being (highly) corroborated in the panoramic sense.

Even if the concept of (efficient) cause were actually the strict fruit of the account of a certain (sensible) impression made on the human mind, the presence of that concept in the human intellect cannot have as a necessary condition the account of the (sensible) impression made on the human intellect by the specific mode of chaining that is a chain of events repeating itself identically under identical circumstances; because any observed sequence making an impression on the human intellect, whether the sequence in question is repeated (and whether it is identically repeated under identical circumstances), would then be capable of producing the impression of the action of an efficient cause. But, although sensible experience is only able to corroborate our ontological concepts and the suprasensible is only made of impressions, the relation of the human mind to the latter is actually active (and not only passive, i.e., not only made of observations and impressions).

Our intellect is active towards them in that it assesses them and relies on them. Whether the human intellect confuses sensible impression with sensible experience when thinking some ontological concept (for instance, the concept of efficient cause) to be (highly) corroborated by sensible experience changes nothing to the fact that it then thinks the ontological concept in question to be (highly) corroborated by sensible experience; just like the fact that it confuses sensible impression with sensible experience when thinking some ontological concept (for instance, the concept of efficient cause) to be confirmed by sensible experience changes nothing to the fact that it then thinks the ontological concept in question to be confirmed by sensible experience.

Yet the human intellect doesn’t only endorse this or that ontological concept according to whether it thinks or not the latter to be empirically confirmed or (either empirically or panoramically) corroborated; it also tries to articulate them with each other in the way that makes most sense in view of each other, in view of sensible experience, and in view of corroboration in a panoramic sense. I intend to show (a few lines later) that those causal relational properties that are identically repeated when identical circumstances are repeated make most sense when understood as constitutive properties that are, besides, correspondent to intrinsically necessary dispositions that—in addition to their presence at the “substantial” level in the entity—apply to any moment witnessing the presence of some circumstances. I cannot say more about it for now.

Just like those causal relational properties identically repeated (when identical circumstances are repeated) are part of the constitutive properties of a (singular) material entity endowed with such properties, they’re part of the constitutive properties of a generic material entity endowed with such properties. Therefore they as much belong, so to speak, to the adequate definition for the concept whose object is the singular entity in question as they belong, so to speak, to the concept whose object is the generic entity in question.

The “eye of the world” that is the human (not in the sense that he is a way for the universe of seeing, knowing, the universe—either correctly or approximately—but in the sense that he is able, mandated, to approach exact knowledge of the universe without ever reaching it) is notably able (and mandated) to approach exact knowledge of the material essences in material entities without ever reaching said knowledge. (Approximative) knowledge of the “laws of nature” is, precisely, part of the (approximative) wider knowledge of “material essences.”

What “material essence” exactly means in the article is the set of the constitutive properties in a material entity (which—as I intend to develop a few lines later—are not all “natural” properties and are not all “substantial” properties). Grasping perfectly (or almost perfectly) a material essence in a material entity amounts to obtaining a perfect (or almost perfect) definition of the concept for the material entity in question.

When a material entity is rendered the object of a concept, the concept in question always means, indeed, the entity in question strictly taken from the angle of its constitutive properties, i.e., strictly taken from the angle of its material essence. As for the definition socially correspondent (in some language) to a concept whose object is a material entity, it exposes what the language in question thinks are the constitutive properties of the material entity in question. Hence the concept in question and its socially correspondent definition are held as synonyms in the language in question.

Part of the cognitive process leading to move closer to perfect knowledge of a material essence consists of selecting some socially admitted definitions and questioning their validity. It is worth specifying that pseudo-definitions must be distinguished from actual definitions. While the latter only deal with constitutive properties (and with the totality of the constitutive properties), the former deal with any kind of property.

Also, while the latter notably include ones socially admitted, which, in some language, are attached to correspondent concepts and accordingly held to be synonymous with the concepts in question, the former are of strictly private use. Just like the fact that some language deems some definition to be true (i.e., to expose adequately the totality of the constitutive properties in the correspondent concept’s object) doesn’t render the definition in question true, the fact that some language deems two terms or a term and a sequence of terms (when taken in a certain conceptual acceptation) to be synonymous (i.e., endowed with equivalent senses) doesn’t render them true synonyms. While a concept (strictly) means its object taken from the angle of its constitutive properties (setting aside for now the case of those concepts with meaning-modalities), its definition (strictly) exposes what the definition in question claims are the constitutive properties in the concept’s object.

Whether a concept deals with a singular entity (either material or ideational), a genre (either material or ideational), or a property (either material or ideational), its socially admitted definition (in some language) is socially deemed to be synonymous with its meaning, i.e., with its object taken from the angle of its constitutive properties.

For instance, if some language defines the genre duck as “a waterbird with a broad blunt bill, short legs, webbed feet, and a waddling gait,” then the term “duck” (when taken in the right conceptual acceptation) and sequence “a waterbird with a broad blunt bill, short legs, webbed feet, and a waddling gait” will be held as synonymous in the language in question. In other words, the concept duck’s meaning (i.e., the object referred to as duck taken from the angle of its constitutive properties) will be deemed to be synonymous with the meaning of the above-evoked sequence.

Just like any concept for a genre (whether it deals with a genre of ideational singular entities or a genre of material singular entities) deals with some of the generic properties of some singular entity, any concept for a singular entity (whether it deals with an ideational singular entity or a material singular entity) deals with the whole of the constitutive properties in its object.

The set of those generic properties in a singular entity (whether it is material or ideational) that are constitutive is only part of the constitutive properties; but, while the constitutive properties are only part of the properties in a material singular entity, all properties in an ideational singular entity are constitutive properties.

Just like any material entity is a singular (rather than generic) entity, any ideational entity is a singular (rather than generic) entity. Also, just like any entity (whether it is material or ideational) falls within some genres, the expression “generic entity” is only a convenient way of designating a genre to which some entity (either material or ideational) happens to belong. For instance, the singular material entity that is a singular duck belongs to the “generic material entity” that is the genre duck; and the singular ideational entity that is the singular Idea for some singular duck belongs to the “generic ideational entity” that is the generic Idea for the genre duck.

In both cases, the genre in question—instead of being an entity strictly speaking—is only a set of constitutive properties. Also, in both cases, those generic properties that are constitutive are only part of the constitutive properties; but, while the constitutive properties of a singular material duck are themselves only part of the duck’s properties, all properties in the singular ideational model for the singular material duck in question are constitutive properties.

A concept for an alleged singular entity (whether it is material or ideational) always deals (only) with the set of the constitutive properties in its object; but, while a concept for an ideational singular entity deals with all properties in its object (as all properties in its object are constitutive), a concept for a material singular entity deals with only some part of the properties in its object. The hypothetical entity modeled in an ideational entity must be distinguished from the ideational entity. Here I won’t deal with what are the properties in an ideational singular entity apart from those related to how it designs the hypothetically materialized entity modeled within it.

All properties in a genre or in a property are constitutive, not all properties in a singular entity; but here I will leave aside the case of those concepts dealing with a property (apart from noting that those concepts also deal with their respective object taken from the angle of its constitutive properties). Just like a same word can subsume several concepts (for instance, the word “duck”), a same concept can subsume several meanings—namely a general meaning and its several modalities (paradoxically including the general meaning itself taken in isolation).

For instance, the concept of color includes a general meaning for which the socially admitted correspondent definition is “a visual characteristic distinct from those visual characteristics that are the size, the shape, the thickness, and the transparency;” and subaltern, specific meanings—including one for which the socially admitted correspondent definition is “a visual characteristic that, besides being distinct from those other visual characteristics that are the size, the shape, the thickness, and the transparency, finds itself associated with a wavelength.”

If correctly constructed (what is tantamount to saying: if correctly defined), a concept for some material entity (or for some generic material entity) endowed with only one meaning is then perfectly mirroring the modeled constitutive properties inscribed in the ideational essence of its object (without the ideational essence containing only those properties in the modeled entity that are constitutive); just like, if correctly constructed (what is tantamount to saying: if correctly defined), a same concept for several material entities (or several generic material entities) endowed with a general meaning and some modalities for the latter is then perfectly mirroring the modeled constitutive properties inscribed in the respective ideational essence for the respective object of each of its meaning-modalities (without the respective ideational essences containing only those properties in the respective modeled entities that are constitutive).

Just like a good definition generally speaking (i.e., a good definition as much in the case of ideational as in the one of material objects, as much in the case of generic objects as in the one of singular objects, as much in the case of entities-objects as in the case of properties-objects, and as much in the case of real objects as in the case of unreal objects) strictly deals with the correspondent concept’s object taken from the angle of its constitutive properties (or with the constitutive properties of one of the correspondent concept’s objects), the set of the constitutive properties in a (singular) material entity form what may be called its material essence.

Yet a proper presentation of the way the essence in any material entity is subdivided into four distinct essences (namely the ideational essence, the material essence, the natural essence, and the substantial essence) requires preliminary partial presentation of the subdivision between the several kinds of property totally or partly present in any entity (whether ideational or material)—and of the subdivision between the several kinds of origin and of permanence (or provisority) for existence in an existent entity (whether ideational or material).

The properties in an individual entity (at some point) are notably classified as follows:

- Constitutive properties vs. accessory properties.

- Intrinsically necessary properties vs. intrinsically or extrinsically contingent properties.

- Extrinsically necessary properties vs. intrinsically necessary or extrinsically contingent properties.

- Unique properties vs. generic properties.

- Relational properties vs. non-relational properties.

- Existential properties vs. non-existential properties (i.e., qualities).

- Fundamental properties vs. secondary properties.

- Innate properties vs. emergent properties (whether in the general sense of posteriorly appearing properties—or in the precise sense of posteriorly appearing properties bringing about novelty in the world in terms of non-existential characteristics, i.e., in terms of qualities).

- Permanent properties in an intrinsically necessary mode vs. properties with an extrinsically necessary permanent character or an intrinsically necessary provisory character.

- Provisory properties in an intrinsically necessary mode vs. properties permanent in an extrinsically or intrinsically necessary mode.

- Compositional properties (i.e., about what the entity is made of) vs. formal properties (i.e., about how the entity is shaped from its matter).

- Dispositional properties (i.e., about what the entity would do if put in presence in some circumstances at some moment) vs. concrete properties.

As for the modes of origin and permanence (or provisority) for an entity, they’re notably classified as follows. 1) Intrinsically necessary entities versus intrinsically or extrinsically contingent entities. 2) Permanent entities in an intrinsically necessary mode versus entities provisory in an intrinsically necessary mode—or permanent in an extrinsically necessary mode.

An intrinsically necessary property of the strong kind is one that an entity (whether it is material), at some point, cannot but possess independently of what are the entity’s relations at any point of its existence (and independently of whether the entity has relations at any point of its existence); except the entity in question needs to be presently existent (if it is to possess the property in question), what requires some relations at some point before in the case of any entity different from God.

An intrinsically necessary property of the weak kind is one that an entity, at some point, cannot but possess independently of what are the entity’s relations at any point of its existence (and independently of whether the entity has relations at any point of its existence); except the entity in question needs to be presently existent and intact (if it is to possess the property in question), what requires some relations at some point before in the case of any entity different from God.

Just like the entity’s existence at the present time is a necessary, sufficient cause for any intrinsically necessary property of the strong kind that is then present in the entity, the entity’s existence and integrity at the present time is a necessary, sufficient cause for any intrinsically necessary property of the weak kind that is then present in the entity. An intrinsically necessary property (whether it is of the strong kind) that is dispositional is a modality of an intrinsically necessary property; but not any dispositional property is an intrinsically necessary property.

An extrinsically necessary property is one that an entity, at some point, cannot but possess due to the entity’s existence and to the combination, at some point before, between the entity’s existence, an intrinsically necessary property (for instance, a dispositional intrinsically necessary property) in the entity, and one or more relations in which the entity finds itself engaged at that anterior moment.

For instance, the property for a point mass, at some point, of exerting an attraction force towards another one that is “proportional to the product of the two masses and inversely proportional to the square of the distance between them” is a relational extrinsically necessary property that is a forced product of the entity’s existence at that point and of the combination (at some point before) between the entity’s existence, another relational property (namely the presence of another point mass somewhere), and a dispositional intrinsically necessary property (namely the property of exerting an attraction force such as described above when another point mass is present somewhere).

An intrinsically contingent property is one whose existence, at some point, in an entity finds a necessary, sufficient cause in the fact that the entity’s existence at that point is added to the occurrence, at some point before, of a combination between the entity’s existence, an intrinsically necessary property in the entity, and one or more relations on its part at that anterior moment.

Just like any intrinsically contingent property is one extrinsically necessary, any extrinsically necessary property is one intrinsically contingent. An extrinsically contingent property is one that is present at some point in an entity as a random product of the fact that the entity’s existence at that point is added to the occurrence, at some point before, of a combination between the entity’s existence, an intrinsically necessary property, and one or more relations; but which finds in that fact whose random product it is a necessary (though not-sufficient) cause.

No relational property (except in the case of God) is one intrinsically necessary; but any relational property (except in the case of God) is either extrinsically contingent or extrinsically necessary. A property that an entity, at some point, possesses because of its present existence and of the combination (at some point before) between a free volition on its part, its existence, one ore more relations on its part, and an intrinsically necessary property in it is a modality of an extrinsically contingent property.

Just like a property that is, at some point, permanent is a property that is, at the considered moment, doomed to continue to exist in the entity without any interruption (so long as the entity will keep up being existent), a property that is, at some point, provisory is a property that is, at the considered moment, doomed to cease to exist in the entity, either in a determinate (or more or less determinate) future moment in which the entity will be still existent, or in an indeterminate (or more or less indeterminate) future moment in which the entity will be still existent.

An intrinsically necessary property (whether it is of the strong kind) is either permanent or provisory; just like an extrinsically necessary property is either permanent of provisory—and just like an extrinsically contingent property is either permanent or provisory.

A permanent property is either permanent in an intrinsically necessary mode or permanent in an extrinsically necessary mode; just like a provisory property is always provisory in an intrinsically necessary mode.

A property that, at some point, is permanent in a strong intrinsically necessary mode is a property that, at the moment in question, is doomed to continue to exist in the entity (so long as the latter will keep up existing) independently of what are the entity’s relations at any point of its existence (and independently of whether the entity has relations at any point of its existence); except the entity in question needs to be presently existent (if the property in question is to be presently permanent), what requires some relations at some point before in the case of any entity different from God.

A property that, at some point, is permanent in a weak intrinsically necessary mode is a property that, at the moment in question, is doomed to continue to exist in the entity (so long as the latter will keep up existing) independently of what are the entity’s relations at any point of its existence (and independently of whether the entity has relations at any point of its existence); except the entity in question needs to be presently existent and intact (if the property in question is to be presently permanent), what requires some relations at some point before in the case of any entity different from God.

Just like the entity’s existence at the present time is a necessary, sufficient cause for the permanence of any property that is presently permanent in a strong intrinsically necessary mode in the entity, the entity’s existence and integrity at the present time is a necessary, sufficient cause for the permanence of any property that is presently permanent in a weak intrinsically necessary mode in the entity.

A property that, at some point, is provisory in an intrinsically necessary mode is a property that, at the moment in question, is doomed to cease to exist in the entity (at a future moment—either determinate (or more or less determinate) or indeterminate (or more or less indeterminate)—in which the entity will be still existent) independently of what are the entity’s relations at any point of its existence (and independently of whether the entity has relations at any point of its existence); except the entity in question needs to be presently existent (if the property in question is to be presently provisory), what requires some relations at some point before in the case of any entity different from God.

The entity’s existence at the present time is a necessary, sufficient cause for the provisory character of any property that is presently provisory in an intrinsically necessary mode in the entity. A property that, at some point, is permanent in an extrinsically necessary mode is a property that, at the considered moment, is permanent because of the entity’s present existence and because of the combination (at some point before) between the entity’s existence, an intrinsically necessary property in the entity, and one or more relations on its part. Any property permanent in an extrinsically necessary mode is also permanent in an intrinsically contingent mode—namely that those things form a necessary, sufficient set of causes for its permanence.

An intrinsically necessary entity is one that, at some point, cannot but exist independently of what are the other entities in the universe (and in the ideational realm) at any point (and independently of whether other entities are existent at any point in the universe and in the ideational realm).

As for an extrinsically necessary entity, it is one that, at some point, cannot but exist due to the combination, at some point before, between another entity’s existence, an intrinsically necessary property in that other entity, and one or more relations in which that other entity finds itself engaged (at that anterior moment).

Just like an entity that cannot but exist in an eternal mode (i.e., in a mode devoid of any beginning in time and any ending in time) is a modality of an entity that is intrinsically necessary, an entity that is self-created but cannot escape its self-creation is another modality of an entity that is intrinsically necessary.

An intrinsically contingent entity is an entity whose existence at some point finds a necessary, sufficient condition in the fact that a combination occurs, at some point before, between another entity’s existence, an intrinsically necessary property in that other entity, and one or more relations in which that other entity finds itself engaged (at that anterior moment).

Just like any intrinsically contingent entity is one extrinsically necessary, any extrinsically necessary entity is one intrinsically contingent.

An extrinsically contingent entity is an entity that, at some point, finds itself, either existent because of the entity’s random self-creation from nothing at some point before, or existent because of the entity’s random apparition, at some point before, from a combination happening even earlier between another entity’s existence, an intrinsically necessary property in the latter, and one or more relations on the latter’s part; and whose present existence finds a necessary, sufficient cause in the fact of having been engendered in one or the other of those ways.

Just like God is an intrinsically necessary entity in an inescapable eternal mode, the universe is both an extrinsically necessary entity with regard to God—and an extrinsically contingent entity in a randomly self-created mode with regard to the nothingness preceding the universe.

No entity apart from the universe can be one, at some point, both extrinsically necessary (from some respect) and extrinsically contingent (from some respect). Just like an entity permanent in an intrinsically necessary mode at some point is an entity that, at the considered moment, is doomed to continue to exist independently of what are the entity’s relations (and independently of whether the entity has relations), an entity provisory in an intrinsically necessary mode at some point is an entity that, at the considered moment, is doomed to cease to exist at a future moment—either determinate (or more or less determinate) or indeterminate (or more or less indeterminate—independently of what are the entity’s relations at any point of its existence (and independently of whether the entity has relations at any point of its existence).

As for an entity permanent in an extrinsically necessary (but intrinsically contingent) mode at some point, it is an entity that, at the considered, is doomed to continue to exist because of the entity’s present existence and because of the combination (at some point before) between the entity’s existence, an intrinsically necessary property in the entity, and one or more relations on its part; and which finds in the set of those causes a necessary, sufficient set of causes for its permanence.

Just as an existent entity that is permanent at a certain moment is an entity that, at the concerned moment, is doomed to continue to exist without any interruption, an existent property that is permanent in a certain entity at a certain moment is a property that, at the concerned moment, is doomed to continue to exist without any interruption in the entity (so long as said entity will exist).

Just as an existent entity that is provisory at a certain moment is an entity that, at the concerned moment, is doomed to cease to exist either at a determinate (or more or less determinate) moment or at an indeterminate (or more or less indeterminate) moment, an existent property that is provisory at a certain moment is a property that, at the concerned moment, is doomed to cease to exist in the entity either at a determinate (or more or less indeterminate) moment in which the entity will still be existent, either at an indeterminate (or more or less indeterminate) moment in which the entity will still be existent.

Just as an existent entity, at a certain moment, is, at the considered moment, either existent in an intrinsically necessary mode, or existent in an extrinsically necessary (but intrinsically contingent) mode, or existent in an extrinsically contingent mode, an existent property in a certain entity, at a certain moment, is, at the considered moment, either existent in an intrinsically necessary mode, or existent in an extrinsically necessary (but intrinsically contingent) mode, or existent in an extrinsically contingent mode.

Just as an existent entity, at a certain moment, is, at the considered moment, either permanent in an intrinsically necessary mode, or provisory in an intrinsically necessary mode, or permanent in an extrinsically necessary (but intrinsically contingent) mode, an existent property in a certain entity, at a certain moment, is, at the considered moment, either permanent in an intrinsically necessary mode, or provisory in an intrinsically necessary mode, or permanent in an extrinsically necessary (but intrinsically contingent) mode.

Rings that, at any time, would render anyone who wears them immortal would provide an extrinsically necessary permanence to the human wearing them on his wrists at a given time; but a machine that provisorily keeps someone alive provides neither any extrinsically necessary permanence nor any permanence at all. The universe is permanent in an extrinsically necessary mode with regard to God; but permanent in an intrinsically necessary mode with respect to the nothingness preceding the universe. No entity other than the universe can be permanent in an extrinsically necessary mode.

In its general sense, “the mode of existence” for an entity here means the set of its existential properties over the course of its existence; but, in its stronger sense, here means the set of those existential properties over the course of its existence that are about the origin for an entity’s existence—plus those about whether and how it is permanent or provisory. Unless specified otherwise, the article will resort to that concept in that stronger sense exclusively.

The mode of existence (in the above-evoked strong sense), at some point, for an entity that is, at that point, existent is an existential innate property with strong intrinsic necessity and with strong intrinsically necessary permanence. Yet a material entity is endowed with four essences.

Firstly, the ideational essence—namely the sum of all the properties of an entity over the course of its existence.

Secondly, the material essence—namely the sum of all the constitutive properties of an entity over the course of its existence.

Thirdly, the natural material essence—namely the sum of all those constitutive properties of an entity over the course of its existence that are intrinsically necessary properties, whether of the weak kind or of the strong kind.

Fourthly, the substantial natural material essence—namely the sum of all those intrinsically necessary constitutive properties of the strong kind that are both innate and endowed with intrinsically necessary permanence of the strong kind.

The mode of existence (i.e., those existential properties about whether and how a material entity is necessary or contingent—and about whether and how it is permanent or provisory) is part of the substantial natural material essence. Just like not any existential property in a material entity is part of the substantial natural material essence, not any substantial natural material property is an existential property; but when a material entity loses all or part of its substantial natural material properties, it always loses its property of existing on that occasion—and reciprocally.

In other words, a material entity ceases to exist when (and only when) it loses all or part of its substantial natural material properties. Any substantial property is a constitutive property; but not any constitutive property is a substantial property. Any intrinsically necessary property is a constitutive property; but not any constitutive property is an intrinsically necessary property. Some generic properties are constitutive properties; but not any generic property is a constitutive property.

Some generic properties are intrinsically necessary; but not any generic property is intrinsically necessary. The natural material essence in a material entity is the sum of all the intrinsically necessary constitutive properties (whether intrinsically necessary of the strong kind) in the entity—including (but not only) those intrinsically necessary constitutive properties in the entity that are generic.

My quadripartite approach to the essence in a material entity allows solving a number of ontological problems—including (but not only) the problem of how and when an entity ceases to exist, namely, that a material entity ceases to exist when (and only when) it loses all or part of its substantial natural material properties, a loss that always brings about the one of the property of existing (though the latter is no more part of the substantial essence in a perishable—and, accordingly, provisory in an intrinsically necessary mode—entity than is the property of dying).

What is more, my approach to the essence in a material entity allows solving the ontological problem of the universe’s jump from nothingness. If someone has voluntarily put a hat on his head at some point and wears it right now, the property in him of wearing a hat is an extrinsically contingent property that is the random product of his present existence and of an earlier combination between an intrinsically necessary dispositional property (namely the ability to put and wear a hat in the ongoing context), existence, and several relations (including the relational property of finding himself in a place where the wind doesn’t prevent him from wearing a hat).

More precisely, it is a modality of an extrinsically contingent property that is an extrinsically contingent property associated with free will—namely the considered human’s free decision to wear a hat. So long as the hat remains pulled down on his head, the hat is then permanent in an extrinsically necessary mode.

As for the universe’s birth from nothingness, just like the toothpaste’s gush from the tube at some point is a non-existential extrinsically necessary property in the toothpaste, the universe’s gush from nothingness at some point (namely at the initial instant in our universe) is, with regard to the nothingness chronologically preceding the universe, an extrinsically contingent mode of origin for the universe that is an existential property intrinsically necessary of the strong kind in the universe.

More precisely, it is a modality of an extrinsically contingent existence that consists of existing in a randomly self-created mode. Yet the universe is (at any point) endowed with intrinsically necessary permanence of the strong kind with regard to the nothingness preceding it. The universe, when considered with respect to the nothingness chronologically anterior to the universe, is therefore a material entity endowed with the innate, intrinsically necessary (of the strong kind) property of being extrinsically contingent—and of being permanent in a strong intrinsically necessary mode.

A third ontological problem that my approach to the essence in a material entity allows solving is the problem of the ontological origin for what is commonly called the “laws of nature”—namely the inescapable regularities (when identical circumstances are repeated over the course of time) in causation from a material entity. I explain those regularities as follows.

Among those relational extrinsically necessary properties that are causal and correspondent to a dispositional innate property with intrinsic necessity (of the strong kind) and intrinsically necessary permanence (of the strong kind), some are unique to a number of times in which the circumstances are identically repeated; but the others apply to any moment in which said circumstances are identically repeated. While the latter are of what may be called a strong type, the former are of what may be called a weak type. While the latter are correspondent to a dispositional innate property with strong intrinsic necessity and strong intrinsically necessary permanence that is, in turn, of the strong type, the former are correspondent to a dispositional innate property with strong intrinsic necessity and strong intrinsically necessary permanence that is, in turn, of the weak type.

For instance, when the ball’s shock with the pool cue causes the ball’s movement, a relational property then present in the pool cue is a causal relational property that consists of causing the ball’s movement; and which is not only a causal relational extrinsically necessary property correspondent to a dispositional innate property with strong intrinsic necessity and with strong intrinsically necessary permanence—but one of the strong type.

In other words, it is a causal relational property that occurs as the forced product of the pool cue’s present existence and of the earlier combination between the pool cue’s existence, a number of relations on its part (including the shock with the ball), and a dispositional innate property (as much with strong intrinsic necessity as with strong intrinsically necessary permanence) that consists of causing the ball’s movement whenever some circumstances are present. Among the substantial natural material properties in an entity, those dispositional innate properties with strong intrinsic necessity and with strong intrinsically necessary permanence that are of the strong type precisely serve as the ontological foundation for the “laws of nature.”

The problem of knowing whether “existence precedes essence” in a material entity is a fourth ontological problem that my approach to the essence in a material entity allows solving. The problem is best understood when put as follows: does a material entity (whether it is endowed with a temporal beginning—and whether it is endowed with intrinsically necessary permanence) have its essence already predefined, preprogrammed, at all stages of its existence?

My take on that issue is the following one. Namely that, in a material entity, the ideational essence indeed precedes material existence (i.e., is indeed predefined, preprogrammed, at all stages of its existence); and that, in a material entity, the substantial natural material essence—and only the latter in the material essence—is also predefined, preprogrammed, at all stages of the entity’s existence.

In other words, while the ideational essence integrally “precedes” material essence, only that component in the material essence that is the substantial natural material essence indeed “precedes” material existence. All other components in the material essence—including the existential property about when the material entity in question ceases to exist in the case where the latter’s mode of existence includes the existential substantial natural material property of being provisory in an intrinsically necessary mode—find themselves “preceded” by material existence for their part. Since the properties covered by the natural material essence are dependent, if not on the entity’s material integrity, at least on the entity’s material existence, they are predefined at no stage of the material entity’s existence—though its existence is a necessary, sufficient condition for those natural properties in the material entity that are intrinsically necessary in a strong mode.

Correctly defining the concept to which some material entity is correspondent consists of correctly presenting those properties in the material entity in question over the course of its material existence that are constitutive—including (but not only) those constitutive properties in the entity that are intrinsically necessary (and therefore natural), whether the latter are intrinsically necessary in a strong mode.

As for correctly defining the concept to which some genre of material entity is correspondent, it consists of correctly presenting those properties in the genre in question that are constitutive; what amounts to (correctly) presenting the whole of the properties present in the genre in question (in that all are constitutive properties), whether they’re intrinsically necessary properties. I will address the respective issues of how a singular man and the generic man should be respectively defined at a later occasion.

Grégoire Canlorbe is an independent scholar, based in Paris. Besides conducting a series of academic interviews with social scientists, physicists, and cultural figures, he has authored a number of metapolitical and philosophical articles. He also worked on a (currently finalized) conversation book with the philosopher, Howard Bloom. See his website: gregoirecanlorbe.com.

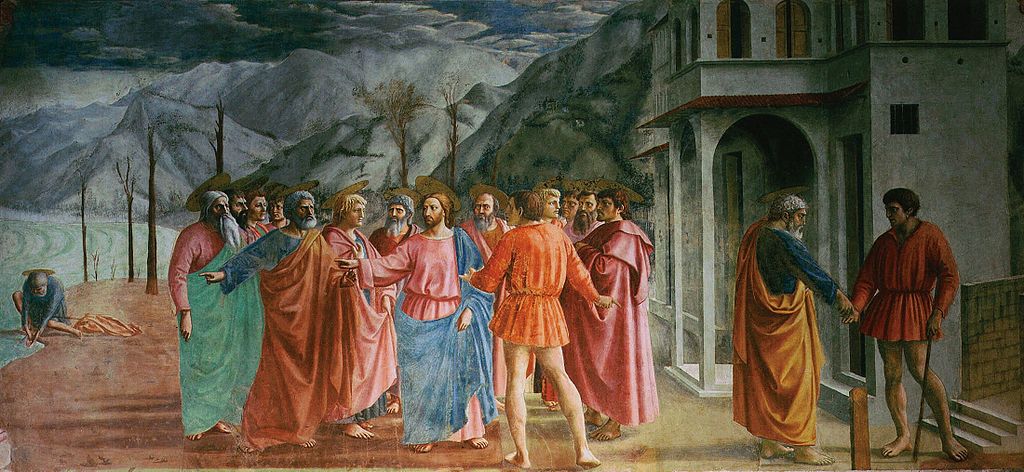

The featured image shows, “The Tribute Money,” by Masaccio; painted in 1425.