“If we exclude the minority of those who do not want to be liberal, everyone declares himself to be liberal or is liberal without knowing it,” many liberals like to say. Others, on the other hand, less optimistic or more demanding, see our era as one of triumphant statism. In France, isn’t there always more regulation and more government? Doesn’t public spending in France represent more than 57% of GDP? So, what is liberalism then?

Heir to the Enlightenment, liberalism is defined as the doctrine that advocates the defense of individual rights. A doctrine that has prevailed in the West for nearly four centuries, although the word is much more recent; neither Montesquieu nor Locke, to name but two, ever called themselves “liberals.” The term liberales (liberals) seems to have first appeared in Spain, in the years 1810-1811. In the Cortes of Cadiz, when the 1812 Constitution was adopted, there were three tendencies: the traditionalists, the Spanish-American deputies, and the liberals. One third of the members of this constituent assembly belonged to the clergy, an active minority of whom were liberals.

But for the majority of French authors, it is indeed the Revolution of 1789, which, daughter of the Enlightenment, is fundamentally liberal (it is only marginally socialist with Gracchus Babeuf). The Revolution is the (or a) decisive moment of rupture in the history of France. It marks the beginning of the period of offensive liberalism. Liberalism was then a left-wing doctrine, which was rejected on the right only after the birth and expansion of socialism. In the aftermath of the great national event, in the tradition of Chateaubriand and Tocqueville, Christian liberals developed the thesis that modern European and Western political history could not be the product of a struggle against Christianity; there was no break with the Revolution – but, on the contrary, continuity and adaptation, a sort of “secularization” of evangelical values. The classic work of Pierre Manent, Histoire intellectuelle du libéralisme. Dix leçons (1987), on the philosophical foundations of liberal thought, is part and parcel of this tradition.

Finally, on the other hand, many other authors, especially foreign ones, insist on the fact that the democratic-liberal history is that of a long and slow evolution, marked by numerous stages, well before the French Revolution. They enumerate in very board strokes, the Cortes of Leon (1188), the Catalan Cortes (1192), the English Magna Carta (1215), the Hungarian Golden Bull (1222), the Swiss Federal Charter (1291), the Swedish General Code of Magnus Erikson (ca. 1350), the Union of Utrecht (1579), the Petition for Rights (England, 1628), the Mayflower Compact of the American Pilgrim Fathers (1620), the Bill of Rights (England, 1689), the Swedish Constitution (1720), the Declaration of Independence (1776), the United States Constitution (1789), etc.

Beyond the differences, according to the times, of countries and leanings (notably with those who grant more to civil society or more to the state), liberalism possesses a fundamental unity which makes it possible to characterize it on the political and economic level. It is the doctrinal foundation, on the one hand, of parliamentary or representative democracy, and, on the other, of the market economy or capitalism. The philosophical conception in which it is rooted makes the individual reason the measure and judge of truth. It is an individualistic rationalism, which, at the origin and in France, is mostly anti-Catholic, anti-clerical and even anti-Christian (which is not the case in the rest of Europe, neither in the Catholic South, in Italy, Austria or Spain, nor in the Protestant countries).

The glorious claims, asserted by the majority of liberals up to the 1980s, allow us to define the liberal system of thought. These claims are numerous and imposing – philosophical eclecticism; individual freedom and freedom from everything beyond the individual; freedom of conscience; freedom of the press; habeas corpus; distinction between civil society and the state; free trade; laissez-faire; religion of the market; defense of private property; distrust of the state; limited government; separation of political and religious powers; taste for savings; respect for balanced budgets; sympathy for representative assemblies and parties of notables; defense of political and associative pluralism; bourgeois relativist morality based on the exaltation of work; contractual freedom; politics of the lesser evil; search for the middle way; compromise as a rule of government; respect for legality; equality before the law; social rights guaranteed by the state (not all liberals agree on this point, of course); the right of citizens to choose and periodically elect their political representatives; and finally, the power of elected officials of wealth and knowledge, if not of true intelligence.

Criticism of liberalism developed very early, from the beginning of the 19th century. The first indictments were drawn up by a host of traditionalist Catholic authors, four of the best known being the Frenchmen Joseph de Maistre and Louis de Bonald, and the Spaniard Jaime Balmes and the former liberal Juan Donoso Cortes. All of them denounced the disease of individualism and economism. As early as the end of the 1840s, Donoso Cortés affirmed that every great political and human question presupposes and envelops a great theological question, that a society sooner or later loses its culture when it loses its religion, that liberal individualism has its natural counterpart in socialist collectivism. There was no severer critic of economism and the great mortar of world revolution than the Marquis de Valdegamas (see the anthology of works by Donoso Cortés, who was secretary to Queen Isabel II, deputy and minister plenipotentiary, Théologie de l’histoire et crise de civilisation (Theology of History and the Crisis of Civilization).

The founding fathers of anti-capitalism were not only the non-Marxist socialists (before Marx and the Marxists), but also, and rather, the counter-revolutionary thinkers, who were succeeded by the social-legitimists. Nowadays, the radical critique of liberalism remains largely indebted to the thinkers of the 19th century, and to the legions of later authors, socialists, socialist-nationalists, nationalist-republicans, monarchist-legitimists, conservative-revolutionaries (such as, Carl Schmitt), non-conformist personalists of the 1930s, fascists, revolutionary syndicalists, anarchists, and Marxist socialists.

Nearly forty years ago, two Sorbonne academics, Raymond Polin and his son Claude Polin, opposed and debated each other in a suggestive essay: Le libéralisme oui, non. Espoir ou peril? (Liberalism, Yes or No? Hope or Peril?). The recent criticisms of Christopher Lasch, Michel Onfray, Jean-Claude Michéa, Alain de Benoist, even the communist Michel Clouscard, or the economist and supporter of the Woke movement, Thomas Piketty, to name but a few, are only recent echoes of an already old controversy. Pleas and accusations hardly vary; only the number of followers of one camp or the other fluctuates.

Liberalism is reproached above all for being the carrier of the disease of individualism. It is said to have the defect of seeing the world as a market; its logic, purely economic, is that of profit. It enslaves the producing classes, strengthens the power of finance, tramples traditional values, dissolves societies, foments ethnic and religious divisions in the name of multiculturalism.

Besides individualism, the most solid accusation against liberalism is twofold. First, is its ideological link with the capitalist economic system (freedom of exchange must allow the substitution of the bad politics of men by the natural and beneficial circulation of goods). Second, is its negation of politics, or its unpolitical character, which follows directly from its defense of individualism. The negation of the “permanent imperatives of politics,” which results from any consequent individualism, leads to a political practice of distrust, to a negative attitude towards any political power and any form of state. From a philosophical-political point of view, there is no liberal politics of a general character – but only a liberal critique of politics.

Anti-liberals thus claim that liberalism always tends to underestimate the state and the political, and that it is always associated with capitalism, whatever its form, private or public, agrarian, industrial, entrepreneurial, managerial or financial. But is this always the case? “No,” resolutely answers the Italian sociologist, Carlo Gambescia, professor at the Scuola di Liberalismo of the Fondazione Luigi Einaudi (Rome). His thesis, debatable but solidly argued, is expounded in an essential work that was published in Italy under the title, Liberalismo triste. Un percorso de Burke a Berlin (Sad Liberalism. From Burke to Berlin). It was then translated and prefaced in Spain by the political scientist, Jerónimo Molina Cano, a recognized specialist in the works of Raymond Aron, Julien Freund and Gaston Bouthoul. One can only deplore the absence of a French version of this work, which has no equivalent in France.

Let us summarize and comment on the main arguments of this innovative work. Gambescia distinguishes four liberalisms; to do so, he uses in each case the suffix -archic (which corresponds to a notion of command, power, regime or political theory). There is, he says, micro-archic, an-archic, macro-archic and archic liberalism. The reader will now forgive me for having to quote a whole series of thinkers, but Gambescia’s classification cannot be understood otherwise.

The first liberalism, micro-archic, is a current of thought going back to David Hume, Adam Smith and the Scottish precursors of the 18th century. It continued in the 19th and 20th centuries with Frédéric Bastiat, Gustave de Molinari, Carl Menger, Ludwig von Mises, Friedrich Hayek, the early first Robert Nozick and even Ayn Rand. One could also compare it to the authors of the Chicago School of Economics (with Nobel Prize winners, Milton Friedman, George Stigler, Gary Stanley Becker, Ronald Coase and Robert E. Lucas). It is a legal-economic liberalism, based on the idea of a “minimum state,” of a power with reduced dimensions, and thus, “micro-archic,” This liberalism pursues individual interest, guided by the invisible hand of the market. It dislikes the state and taxes, without calling for their abolition. The state fulfills here only a residual function, as the legitimate holder of force for its internal and external use.

The second liberalism is an-archic. It is libertarianism; or, to better translate the American expression, “libertarianism,” which has many points in common with the Austrian School. It is represented in the twentieth century by thinkers, such as, Murray N. Rothbard, Hans Hermann Hope and Walter Block. These an-archic or libertarian thinkers reject the very idea of a minimum or residual state, which they replace with the utopia of the absolute free exercise of individual rights, in particular life, liberty and property. For them, the state, whether democratic or dictatorial, is always the worst aggressor of the persons and properties of the citizens.

The third, macro-archical liberalism, was born with the English utilitarian, Jeremy Bentham, in the 18th-19th centuries and developed with John Stuart Mill in the 19th century. In the twentieth century, this third filiation led to the early John Rawls, to Rolf Dahrendorf and John Dewey. We can also link it to John Locke (17th century), Emmanuel Kant (18th century) and John Maynard Keynes (20th century). What is important here is the prevalence of the idea of a specific form of common good. The state is not content to be the guarantor of laws and law; it must be interventionist. It must impose upon itself the task of fostering equal starting conditions for all citizens.

These thinkers allow and justify an increasingly invasive power, in particular through fiscalism. The aim is to artificially level the interests of individuals, which, in experience, does not really generate a more just society, but rather a public bureaucracy that is more invasive and suffocating every day. This macro-archical liberalism is contractualist (supporter of the social contract of Hobbes and Locke). It is very close to social liberalism and redistributive social democracy. It is perhaps worth recalling here that, paradoxically, not only did Roosevelt’s and Truman’s economists admire Keynes, but also Hitler’s economists, such as Dr. Schacht. The Keynesians, for their part, admired Hitler’s economic policies (see Keynes’ preface to the German edition of the General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money, 1936).

Finally, there is a fourth liberalism, archaic, realist, possibilist, without illusions; or, as Pierre Manent puts it, “melancholic,” which does not trust the market, and which wants to serve the individual, while defending the importance of political science. The pages that Carlo Gambescia dedicates to this liberalism are among the most original and substantial. Archaic liberalism, he explains, admits reality, and recognizes the existence of power as an inescapable component of social and political life. Politics is for him the sociological articulation of polemos, the theater of conflicts and recurring struggles. He is conscious of the imperfect nature of man and society, of the fragility and the precariousness of the human conquests, and of the possible corruption of all the institutions. For this liberalism, the conjunction of individual interests does not always lead spontaneously and artificially to the general interest.

As history shows, it is sometimes necessary to resort to iron and fire. In the 19th and 20th centuries, the names of the arch liberals are Edmund Burke, Alexis de Tocqueville, Vilfredo Pareto, Gaetano Mosca, Max Weber, Guglielmo Ferrero, Robert Michels, Benedetto Croce, Simone Weil, Bertrand de Jouvenel, Jules Monnerot, José Ortega y Gasset, Wilhelm Röpke (and all the proponents of the social market economy), Raymond Aron, Gaston Bouthoul, Julien Freund, Jules Monnerot, Maurice Allais, Harold Laski, Giovanni Sartori, Eric Voegelin, Isaiah Berlin, and nowadays Dalmacio Negro Pavón, Pierre Manent, Chantal Delsol, etc.

Archaic liberalism abhors utopian unrealism. Four works, chosen from among those Gambescia cites, exemplify and measure this. In Socialist Systems (1902-1903), Pareto writes: “Every society, if it is to survive, must sooner or later adopt measures to prevent acts that would endanger its very existence. There are only two ways to proceed. One can take away the freedom of men to perform these acts, and thus prevent the dreaded evil; or, on the contrary, one can leave men free and repress harmful acts, directly or indirectly, leaving men to bear the consequences of their acts. Freedom has, as its complement and correction, responsibility – the two are inseparable. If one does not want to have recourse to the second of the means indicated [one can liberate men by making them bear the consequences], one must necessarily have recourse to the first [suppressing liberty to prevent], unless one wants the ruin of society.”

In History as Thought and as Action (1938), the famous Italian anti-fascist thinker, Benedetto Croce, takes the opposite view from Fukuyama and the American democrats and neo-conservatives who advocate the export and establishment of democracy in the world (a doctrine that we know today is in reality a screen for American imperialism). Croce, well known for rejecting the possibility of a strong identity between a contingent economic system (liberism) and an immanent principle (liberalism), writes these words: “The liberal conception, as a religion of development and history, excludes and condemns, under the name of ‘utopia,’ the idea of a definitive and perfect state, or a state of rest, in whatever form it has been proposed or may be proposed, from the Edenic forms of earthly paradise, from those of the golden ages and the lost paradise of Jauja, to the variously political ones of ‘one flock and one shepherd,’ of a humanity enlightened by reason or calculation, of a totally communist and egalitarian society, without external or internal struggles; from those conceived by the naive popular spirit, to those reasoned by philosophers like Immanuel Kant.”

Gambescia drives the point home with a timely reference to the sad experience of “exporting Western democracy” to Afghanistan, a “pride of reason” that has led to a disregard for the country’s traditions and cultural substratum. He recalls the role played by President Hamid Karzai, the man from the United States, later accused of having received CIA funding. These few premonitory pages would deserve to be updated because we know since then that the opium trade has been increasingly flourishing under Karzai’s mandates (2001-2014), that he was dropped by the Americans when he got closer to Iran and Pakistan, that he was then an advisor to the government in Kabul, and that he finally negotiated with the Taliban in August 2021 (the Taliban suddenly became “moderate” through the magic of words and propaganda), as part of a “national reconciliation process” and a “peaceful transfer of power.”

The third characteristic text of realist liberalism, which we shall quote, is that of Wilhelm Röpke. The German ordo-liberal writes in The Social Crisis of Our Time (1942): “… a free market and performance competition do not just occur—as the laissez-faire philosophers of historical liberalism have asserted—because the state remains completely passive; they are by no means the surprisingly positive product of a negative economic policy. They are, rather, extremely fragile artificial products which depend on many other circumstances and pre- suppose not only a high degree of business ethics but also a state constantly concerned to maintain the freedom of the market and of competition in its legislation, administration, law courts, financial policy and spiritual and moral leadership, by creating the necessary framework of laws and institutions, by laying down the rules for competition and watching over their observance with relentless but just severity.”

Finally, the fourth example is that of the French sociologist and professor at the University of Strasbourg, Julien Freund. The author of The Essence of Politics (1965), said evocatively: “Politics passes, politics remains.” According to Freund, the political constitutes an essence for two reasons: on the one hand, it is one of the constant, fundamental, impossible to remove categories of human nature and existence; and, on the other hand, it is a reality that remains identical to itself, in spite of variations in power, regimes and changes in borders.” Man “is capable of transforming society like a demiurge, but only within the limits of the presuppositions of politics. In other words, society allows itself to be disciplined, to be formed, to be deformed…. The demiurge is the master of the forms, not of the essences.” He added without wavering: when a political unit ceases to fight it ceases to exist.

For the archaic liberal or realist thinker, without a political decision and a public force to defend it, the right to property has no chance of enduring. The political force pre-exists the right. This means that the conjunction of interests always has a political nature in the sense of polemos. Law without a sword to guarantee and defend it can easily be trampled and violated. No written constitution can last, if there is no solid executive, no coherent oligarchy able to defend it. There can be no serious international policy without knowing and admitting the place, and determining role of, force and reason of state.

The archaic liberal respects the constants of politics or meta-politics that are the distinction between the governors and the governed, the Iron Law of the oligarchy (subject of Dalmacio Negro Pavón’s book, 2015); the alternation of phases of progress and decadence, of order and disorder; and finally, it recognizes or never excludes the distinction between friend and foe, fundamental and recurrent in the political sphere.

The explanatory model of liberalism that Gambescia proposes has many merits, but it is obviously not perfect. Thomas Hobbes and Montesquieu, who belong to the history of liberalism, are absent from his classification. “They are,” he says, “two problematic thinkers, difficult to classify in my schema.” Hobbes, a progressive individualist, who trusts the role of the state, could be brought closer to the macro-archical liberals, while Montesquieu, who believes in the spirit of laws and gentle commerce, could be a fellow traveler of micro-archical liberals.

On the other hand, Gambescia’s judgment of Rousseau remains partial and uncertain. He takes up the thesis of the Israeli historian, Yaakov Talmon, on the totalitarian democracy of Rousseau (Robespierre’s teacher) and on the similarities between Jacobinism and Stalinism. Indeed, in the thought of the author of the Social Contract, the citizen is subjected to a higher law that Rousseau is compelled to admit as yje citizen’s own ignored will. And this is enough, according to the Italian sociologist, to exclude him definitively and without other form of trial, from the liberal tradition. But the reality is perhaps more complex and more subtle. Without the triple influence of Rousseau (the anti-Christian democrat-republican), Voltaire (the anti-Christian monarchist absolutist) and Montesquieu (the liberal-conservative monarchist who does not confuse the Christian religion with the forms it may have taken in political society), the French Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen becomes difficult to understand.

Usually, one associates Rousseau correctly with the democratic-republican tradition opposed to the liberal tradition. But Rousseau’s critique is carried out in the name of the demands of liberalism, within liberalism and not outside it. Rousseau appropriates the promises of liberalism. He admits the premises but denounces the consequences. He is a thinker of freedom; he is attached to individual freedom and to the right of property, even though he criticizes the absolute right or the unlimited enjoyment of it, which moreover makes him join here paradoxically Christian traditionalism [Liberalism establishes solidly the right of property and makes of it a strictly individual right, whereas the Christian tradition, regarded it as a natural but social right, limited by the law and the social duties of the owner].

Like all the philosophers of the Enlightenment and liberal thinkers, Rousseau seeks to answer the question of how to be free while obeying laws. Like them, he recognizes the need for a regulating criterion of freedom to counterbalance the individualist conception. Like them, he looks for it but does not manage to find it. His answer is ultimately a sophism – one is free when one obeys the general will. In Sovereignty: An Inquiry into the Political Good (1955), Bertrand de Jouvenel writes on this subject: “Insofar as progress develops hedonism and moral relativism, and individual freedom is conceived as the right to obey appetites, society can only be maintained by means of a very strong power.” Rousseau had undoubtedly the taste of the paradox and the contradiction, but nevertheless the majority of the French republican democrats followed him or were influenced by him. This was the case of Pierre Leroux, Ledru-Rollin, Proudhon (even if he criticizes him), Georges Sand, Napoleon III, etc. and this is not nothing.

Another questionable point in Gambescia’s book is the lightness with which he treats the question of the enemies of liberalism. There is, he says, a so-called “holy alliance between reactionaries, traditionalists and revolutionaries.” Behind the criticism of liberalism lies hidden the radical criticism of modernity, the hatred of the present, common to reactionary traditionalists and revolutionaries. At both extremes, there is the same gnostic rejection of man, marked, for some, by pessimism (the evil in Louis de Bonald or Christopher Lasch); and, for others, by optimism (the good in Karl Marx or Slavoj Zizek). Revolutionary Gnosticism, the main enemy of liberalism, is a sort of vein inspiring the different movements that are traditionalism, positivism, Marxism, anarchism, psychoanalysis, fascism, national socialism, ecologism, progressivism, etc. According to Gambescia, they are all based on the conviction that it is possible to eliminate evil from the world, thanks to the knowledge (gnosis) of the right method to change the course of history. Anti-capitalist and anti-liberal gnosticism implies a real disdain for the real man and facts.

Carlo Gambescia, a rigorous and honest sociologist, slips up here and gives way to being a fiery pamphleteer: “In short, why don’t intellectuals like liberalism?” The answer he gives is confoundingly simple: “To put it bluntly, it’s because they are mental lazybones, who aspire at the same time to social recognition, a distinction that in the marketplace of ideas is within the reach of all those who propose a false but useful idea.”

After having, not without reason, criticized the amalgams and the summary Manichaeism of Zeev Sternhell in The Anti-Enlightenment Tradition, Gambescia falls into the same trap. He claims to support his demonstration by relying on Bonald’s thought. Michel Toda, who to my knowledge is the only French specialist in the thought of the Viscount, is in a better position to give an opinion.

However, in order to take the measure of Gambescia’s misguidance on this point, it is enough to recall here the importance of the dogma of original sin for Donoso Cortès: human nature is neither good nor perverse, but only fallen. “The disruptive heresy, which, on the one hand, denies original sin, while affirming, on the other hand, that man does not need divine guidance – this heresy leads first to affirm the sovereignty of the mind, then to affirm the sovereignty of the will, and finally to affirm the sovereignty of the passions – three disruptive sovereignties. Donoso Cortès also explains: “This is my whole doctrine: the natural triumph of evil over good and the supernatural triumph of God over evil. Therein lies the condemnation of all progressive systems, by means of which modern philosophers, deceivers by profession, lull the people to sleep, those children who never leave childhood.”

It remains to be seen whether, as Gambescia seems to think, liberalism is an inescapable basis of the history of ideas from which variations are possible but only if they are minor. And even more, if the realist liberalism that he rightly defends in his brilliant and enlightening book is still a bearer of future and hope when it has been marginalized and murdered by the other liberalisms?

Arnaud Imatz, a Basque-French political scientist and historian, holds a State Doctorate (DrE) in political science and is a correspondent-member of the Royal Academy of History (Spain), and a former international civil servant at OECD. He is a specialist in the Spanish Civil War, European populism, and the political struggles of the Right and the Left – all subjects on which he has written several books. He has also published numerous articles on the political thought of the founder and theoretician of the Falange, José Antonio Primo de Rivera, as well as the Liberal philosopher, José Ortega y Gasset, and the Catholic traditionalist, Juan Donoso Cortés.

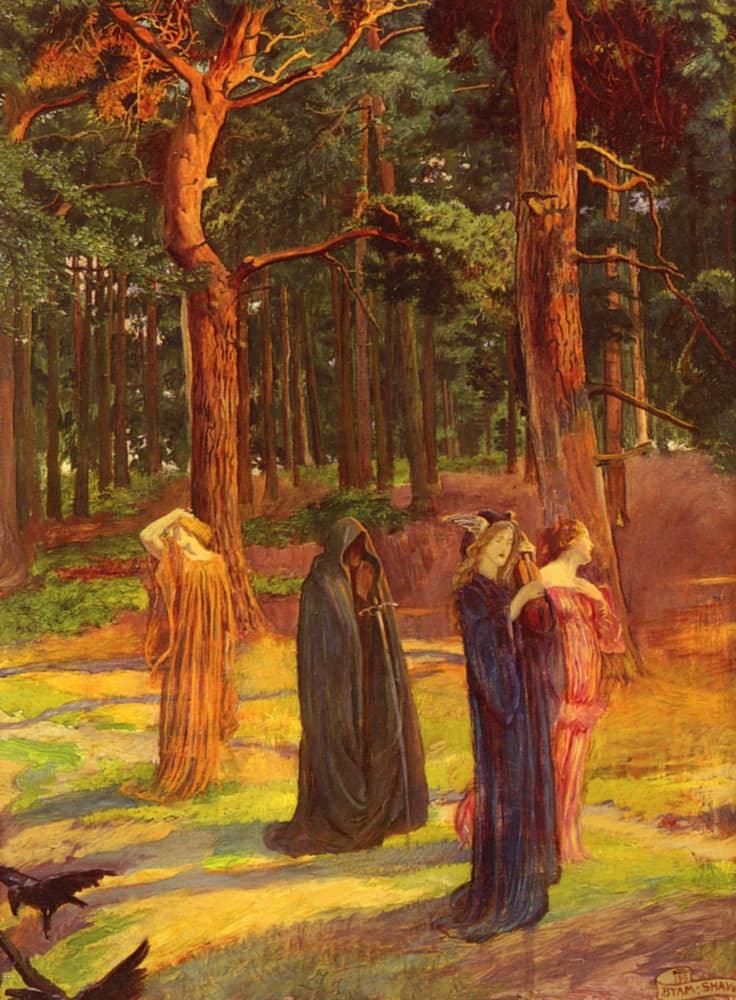

The featured image shows, “A Dirge,” by John Byam Liston Shaw; painyed in 1899.