I.

A few weeks ago, I saw a National Geographic documentary about Franco, in their series about dictators. They had just shown one on that channel about Mussolini, which was simplistic, but acceptable. When they announced this one about Franco, I stuck around to watch. I started perplexed, I continued indignant, and I ended hilarious with laughter – because it is actually quite difficult to put together so many inaccuracies, lies, misrepresentations and nonsense.

But as this type of product is precisely what forms the consciences of the semi-enlightened population, which is the scourge of our time (you only have to see a session of the Congress of Deputies), the matter must be taken very seriously. After all, the little that most Spaniards today know about our own history is what they tell us there. And even worse – it is precisely the version that the Spanish left wants to impose on us by law. Interesting, this convergence of the media-financial oligarchy and the cultural left. But let’s get on with Franco.

Something that was surprising as soon as the documentary began was the limited number of specialists who contributed their knowledge and insight. The only historian with a known work on Franco was Paul Preston, which is not exactly an example of balance. The rest of the specialists turned out to be, if Spaniards, people linked to the groups of the socialist “historical memory,” and if foreigners, likely notable professors at home, but completely unknown in the extensive bibliography on Franco and the Franco regime. Plowing with such oxen, it could already be assumed that the furrow was not going to come out very straight.

Right off the bat – National Geographic informed us that Spain is the second country in the world, after Cambodia, with the highest number of mass graves, which is attributable to Franco, naturally. Source of authority: Amnesty International. But this, as everyone should know by now, is a lie. And the author of this whopper is Miguel Ángel Rodríguez Arias, who has confessed his falsehood (by the way, he did not tell Amnesty International, but a group of people working for the UN).

Within those non-existent graves more than 114,000 disappeared. But this, which the National Geographic piece gives as fact, is also a lie. This figure corresponds to a highly debatable estimate of forced disappearances of children and adults between July 1936 and December 1951, and no doubt many of them were victims of postwar repression. But there is no documentary evidence of the fate of the vast majority of them. From here, however, the narrative framework of the documentary is established – what they are going to tell us is the life of a criminal named Francisco Franco.

A Morocco That Did Not Exist

A veritable criminal – a self-conscious subject, clinging to an intransigent Catholicism, who found in war a channel to give way to his psychological problems. What war? That of Morocco, in whose savagery Franco acquires a taste for “killing his own people,” as we are repeatedly told in this documentary. It is interesting to note how the National Geographic depicts the war in Morocco – as a barbarous exercise of cruelty upon the civilian population, where Franco’s soldiers cut off ears and noses and raped wildly. Is that true?

That war, as every Spanish should know, was not a war of Spain against Morocco, but of Spain (and the Sultan of Morocco) against the rebellious tribes of the Rif. Spain acted there as a “protective” power, and, consequently, had in its ranks thousands of Moroccan soldiers. That is the origin of our troops of regulars, with their red hats, their white capes and their majestic marching formation.

The only function of our army in that Morocco was to control the territory and, therefore, to dominate the Kabyles in Rif who occasionally rose up here and there, so that, in effect, the civilian population was frequently crushed, with the caveat that, equally frequently, in an “irregular” war like that one was, it is rarely possible to distinguish the civilian population from combatants.

But what about all those mutilations and ears and cut-off, and so on? First of all, there is a single photo of legionaries displaying the heads of Riffians. But this photo must be put in context. After the Annual disaster (1921), where the Rif Kabyles annihilated some 11,000 Spaniards (3,000 of them of Moroccan origin), the rebels indulged in a savage orgy of blood.

When the Spaniards recovered places like Monte Arruit or Zeluan, they found that their companions had been tortured, mutilated and burned alive. From then on, it is true that certain units did practice an eye for an eye. But the implicit message of the documentary – raised in such a terrible “school,” Franco became a kind of bloodthirsty beast. But, despite all that, what was Franco’s real part in this story?

Franco – National Geographic tells us – had arrived in Morocco as an officer of the “Regiment of Africa,” where he remained for his entire military career. The fact is Franco was only in a regiment called “Africa” at the beginning of his stay in Morocco, under the command of Colonel Villalba Riquelme, and he did not last more than a year, as he immediately asked to be transferred to the Regulars, and then by 1920 to the newly formed Spanish Legion.

However, the name “Regiment of Africa” remains unchanged throughout the documentary to designate the entire Army of Africa. And thus, we are informed that in 1936, the 30,000 “Moors” of the “Regiment of Africa” came over into Spain. With such figures, it must have been the largest regiment of all time. The documentary, however, is not characterized by the love of accurate detail.

By the way, in that Army of Africa (which is its real name, and not that of “regiment”) there were more Spaniards than Moroccans: 19,624 of the former, 15,287 of the latter. But all that is not of interest for a story like that of National Geographic, where the only objective is to show Franco as the criminal leader of a horde of murderous Moors, looters and rapists, in the same way that established the war propaganda of the Popular Front. Yes, the story oozes blatant anti-Moroccan racism. Is there a progressive lawyer in the room who wants to file a hate crime complaint? A guaranteed win.

The Imaginary Republic

There’s more. It is very funny to see how the documentary next moves to tell us about the advent of the Second Republic. Basically, we are told that the people were not against the Crown, but against Alfonso XIII. As an argument to explain historical change, it is astonishingly frivolous.

Then we are told that, with the fall of the monarchy, a democracy with constitutional guarantees and freedom of the press dawned in Spain, a democracy voted by “men and women all together.”

Let’s see now. First, men and women could not vote “all together,” because until 1933, there was no female suffrage in Spain for legislative elections (and this was because of the opposition of a large part of the left that did not want to grant the vote to women). As for the “constitutional guarantees,” the truth is that during almost the entire Second Republic, such guarantees were suspended, first by the Law of Defense of the Republic and later by the Law of Public Order of 1933, both arising from the imaginings of Azaña.

The Constitution of the Second Republic was only really in force for more than a few months, in the period from its approval in December 1931 to the end of the Civil War in 1939. Preston knows that, but he doesn’t care. And we know you don’t care. I’m afraid National Geographic doesn’t care either. But that reality doesn’t spoil a good story for you, right? Even if it’s a documentary.

And what did happen during that Republic? The National Geographic speaks, yes, of the furious anti-Catholic wave that shook the left, and does not mute the shock of the burning of convents in 1931. But Preston explains it all to us immediately: “In the churches there were golden altars while the people were starving.”

So those people, deep down, deserved what happened to them, right? It is the only time that the documentary talks about religious persecution. It does not say a word about the genocide – which was perpetrated by the Popular Front at the beginning of the Civil War. It is not interested because that might mean that Franco actually had some valid reason to revolt.

More grist in the mill: the documentary talks about the 1934 revolution in Asturias and presents it as a trade union conflict. Not a word about the involvement of the PSOE in the matter, nor about the failure of the uprising in other places (Madrid, for example) nor about the simultaneous separatist uprising in Catalonia.

Of course, it tells us immediately that Franco and “his Moors” were sent to quell the “union protest,” and they did so with the bloodthirsty spirit that characterized them. Not a word about the army of 30,000 armed men that socialists, communists, and anarchists had fitted with arms taken from the Trubia factory and who intended to march on Madrid.

For all that, Franco, did not set foot in Asturias. He was in the capital, on the General Staff, summoned by the (legitimate) Government of the Republic. But that, once again, does not matter. What matters is to blare out the message that Franco massacred “his own people.” The victims of the revolutionaries were not people, apparently.

Thrown at full speed into the void, the National Geographic script informs us that 30,000 prisoners of the Asturian revolt were deported to Africa. Nothing less. I confess that it is the first time in my life that I have heard such a thing. I knew that in 1932 a hundred anarchists were confined to Africa, but that was obviously for other crimes, and also by order of Azaña.

In fact, no one knows exactly how many people were arrested and kept in prison after the 1934 revolution. Why? Because the figures of the repression were exaggerated by the left for propaganda purposes; and then, when the left won in 1936, it was the left itself which obstructed any commission of inquiry. And the fact is that the repression of 1934, although it endured and in some cases was even savage, was far wide of the legend that the Popular Front created. But exactly that is the legend that National Geographic assumes to be historical truth. The way in which the documentary leads us to 1936 is just hideous.

II.

While some charitable soul might want to keep count of the consciences affected by this monstrosity, let’s continue gutting the documentary that National Geographic (via Movistar) has dedicated to Franco in its series, Dictator’s Playbook. We have already seen that its version of the war in Morocco and the advent of the Republic is simply fallacious. The rest of history is yet far falser.

Basically, what the documentary tells us is that Spain was a full democracy that the left had won – not a word about the proven electoral fraud of February, nor about the violence of the spring of 1936-, to the chagrin of the landowners, the bishops and the generals. What was that left like? The documentary doesn’t tell us. The only thing that it does tell us is that the new government did not trust many generals and chose to remove them. From that moment on, the documentary speaks of the “exiled generals” as the main engines of the conspiracy. Wait… Exiles?

As far as I know, only Sanjurjo was exiled after his failed coup in 1932 (which Franco, by the way, did not join). The rest had been taken to distant destinations (Franco to the Canary Islands, Goded to the Balearic Islands). But exiles? Perhaps in the National Geographic they ignore the fact that the Canary Islands and the Balearic Islands are Spanish territory? So this is geography, according to the National Geographic…

But let’s continue with the generals. Because the reality is that, at the time of the Uprising, the majority of the generals preferred to join the Popular Front. Nor does the National Geographic documentary say a word about the murder of Calvo Sotelo, which was decisive for Franco – like many others – in joining the uprising. The story limits everything to Franco’s concern for the threats looming over the Church. It is not a lie, but obviously it is not the whole truth either.

Ruthless Butcher

More caricature… the National Geographic version of Franco’s proclamation as head of the national camp is, quite simply, hilarious. It is difficult to gloss a version in which nothing is true. Therefore, let us limit ourselves to summarizing what actually happened. In a militarily precarious, politically uncertain and economically desperate situation, and seeing the damage that the division of power was causing on the other side, the rebels decided to choose a single leadership. It should have been Sanjurjo, but he died in a plane crash.

Against the opposition of the generals, most closely linked to the republican order, such as Queipo and especially Cabanellas, the majority of the leaders chose Franco as their political and military leader. Why? For his service record and for his good external contacts. Franco’s supporters also made sure that the leadership included command over the entire nascent state. Not everyone liked it, but they all folded. And everything else is literature.

The documentary says that Franco deviated from his route to Madrid to liberate the Alcázar of Toledo, instead of dedicating those troops to the capture of the capital. For what reasons? For propaganda purposes. Old story. It has always caught my attention that, when this episode is recounted, no one realizes that, besieging the apparently irrelevant Alcazar, there were also a good number of Popular Front troops (15,500 militiamen), and that they did not come to Madrid either, but stayed around their goal.

The Alcázar was so important to the Popular Front that Largo Caballero had himself portrayed disguised as a militiaman, at the head of his hosts, marching against the Toledo enemy. Of course, it was a propaganda goal. Everyone wanted to take it.

And the war? Well, the fact is, Franco won it. The documentary admits only once that Franco was effective, but immediately adds the qualifier “ruthless.” It just won’t do that the “evil general” was a good professional. As Preston and his boys tell us, the Popular Front lost the war because the Soviet Union withdrew its military support.

But the truth is that this did not happen until the fall of 1938, and in fact it would not be fully verified until February of 1939. By then the war was already over, after the collapse of the Popular Front at the Battle of the Ebro.

In any case, the National Geographic account has little interest in any of this – its narrative focuses on explaining that Franco (and “his Moors”) went from city to city murdering people. “Massacring his own people,” which is the “heart-rending” message of the documentary. Of the people who died on the other side, not a peep.

Tons Dead And Stolen Children

The documentary gives as fact the figure of 450,000 victims of the Civil War. It is very reckless. To date, no one is in a position to say with total precision how many people died in our war, either in combat or as a result of repression, and only by approximation can we get an idea of the victims of the subsequent repression (this one, yes, attributable to the Franco regime). Why is it so difficult to get the exact number of victims? For multiple reasons.

At the time, no one had a national ID card, which is an invention of 1944. Many of the censuses and registers were burned by the “revolutionary justice” during the first months of the war, both in official buildings and in churches that burned completely (because in the churches there weren’t just the “golden altars” that Preston talks about). There are also numerous examples of people who changed their identities after the war, of people who appear repeatedly in several lists of victims, even of people who appear as victims of one side and on the other at the same time.

Approximate and provisional figures? Some 140,000 fallen in combat, to which must be added around 60,000 victims of the Red Terror and around 80,000 victims of the repression of the victors (until 1959). Those are the ones that more or less generate some consensus. No, not 450,000 deaths. And the once famous “million dead,” as everyone should know by now, does not refer to the actual dead, but adds up the number of births that would have occurred under normal conditions and that the war situation thwarted.

Regarding figures, the documentary supports the thesis of the 300,000 “children stolen” by the dictatorship, a completely absurd thesis that, once again, has been objectively refuted by reality: the case of Inés Madrigal, decided in court in July 2019, showed that this woman, as a child, was not stolen, but voluntarily given up for adoption. And it is relevant because it is the only case – the only one – that has come to trial. The others have not even passed first muster. But this also does not matter. What National Geographic tells us, in the approach inaugurated by former judge Garzón, is that the Franco regime designed a system to snatch their children from pregnant Republican prisoners and give them to families addicted to the regime. Is this true? Is it a lie?

Let’s see. The Franco regime, after the war, chose to give up the children of female prisoners for adoption, but that was a common practice at the time and continues to be so today in many countries (the United States, for example). The same happened with war orphans. In addition, there is the issue of the “children of war” who were deported by the Popular Front to other European countries to keep them away from the war and who immediately found that the war was reaching them. These children were returned to Spain and in many cases their parents were not found.

And then there is, finally, the issue of children given birth by mothers with problems (or without them) and given up for adoption in an irregular way. It is these cases that fed the suspicion of a plot, but, in general, these are events that happened long after the end of the war, happened even in the post-Franco era. If we mix everything with everything and dispense with documentary support, the hypothesis that the Franco regime set up an organized plot to abduct children can emerge, but that falls as soon as one asks for proof that such a plot actually existed. So far, the proof has not been shown and is not likely to be shown. So, everything is a lie. But trying telling that to the National Geographic.

And So We Come To Delirium

For the audacious makers of the documentary, this matter of the supposed “stolen children” serves to establish a surprising thesis, namely – Franco – they say – implemented a system of social engineering (sic) to raise young fanatics who were those kids stolen from their mothers. Any Spaniard who has lived at the time knows that this is an invention (and also very recent). But there are fewer and fewer compatriots who can attest to it, so, once again, National Geographic does not care. And so it goes.

Naturally, and to ensure that nothing is lacking in the repertoire of topics, the documentary tells us that the Valley of the Fallen was built with “slave labor” of political prisoners (Republicans). It is suggested that they were sentenced to forced labor.

As this is a fallacy that no longer holds water, in the same documentary an archaeologist from the CSIC shows up immediately afterwards, and without fear of contradiction, to explain to us that it was actually a penalty redemption system that allowed the inmate to reduce five years of condemnation for each year of work, and that is why many asked for such voluntarily labor. “But not because they liked it, but because the other was worse,” adds the archaeologist immediately, in case we had not understood. Nor does the National Geographic tell us, of course, that in addition to reducing sentences, these prisoners received a salary, and that the inmates were only a small part of the personnel who worked in the Valley. But the script could not put up with any more contradictions.

Is there more? Of course. The learned scriptwriters at National Geographic maintain that Franco froze (sic) Spain for forty years, and they illustrate this assertion with strident images of an eighteenth-century float going around a bullring. It is remarkable because, however you look at it, those forty years were the time of the greatest socioeconomic transformation that Spain has experienced in its entire history, including the last four decades in democracy. Here’s data from the National Statistics Institute on productive sectors:

At the height of 1940, the primary sector (agriculture) occupied 50% of the population, the secondary (industry) 22% and the tertiary (services) 28%, proportions very similar to those of ten and twenty years ago.

But on Franco’s death, in 1975, these proportions were, in approximate figures, 22%, 37% and 36% respectively.

So, Spain had become an industrial country. That is not to mention many other changes that any Spaniard over 55 years of age may remember as part of their own life: the impressive growth of GDP in the 1960s, home ownership, paid vacations, Social Security, the practical disappearance of illiteracy, etc. Or the nationalization of Telefónica, Movistar’s mother company, which is the television platform where National Geographic broadcasts (what a world…).

Regarding illiteracy, the National Geographic documentary, to support its own fallacy of a “frozen Spain,” ends by telling us that the first democratic elections after 1975, which were the 1977 legislative elections, were won by “the left wing.” In other words, Spain, as soon as the terrible tyrant died (as an old man and in his bed, in a public hospital), returned to the Popular Front.

The truth is that in those elections between the UCD of Suárez and the AP of Fraga (both, by the way, Franco’s ministers) garnered about 8 million votes, while the PSOE, the PCE of Carrillo and the PSP of Tierno Galván did not reach that figure. In subsequent legislative sessions, in 1979, the proportions were very similar. Where is the “left wing?” Who the hell documented this documentary?

I better stop, because there is no reason to bore nice people. There is only one question: What have we done to deserve this?

One last note: the head of National Geographic is a man named Gary Knell, who ran the Sesame Street production company for many years and is a member of the Council on Foreign Relations, a famous think-tank linked to the Rockefellers and entirely devoted, for over a century now, to providing intellectual ammunition for US foreign policy and what is called “global governance.”

Perhaps it is just coincidence that the general tone of National Geographic historical documentaries always, always conveys the idea of European guilt in all the ills of the world. And how can these people be interested – you may wonder – that the ultra-left version prevails about Franco and the History of Spain? The answer is so interesting that it deserves another article. There’s no room for it now. But maybe you have already drawn your own conclusions.

José Javier Esparza, journalist, writer, has published around thirty books about the history of Spain. He currently directs and presents the political debate program “El gato al agua,” the dean of its genre in Spanish audiovisual work.

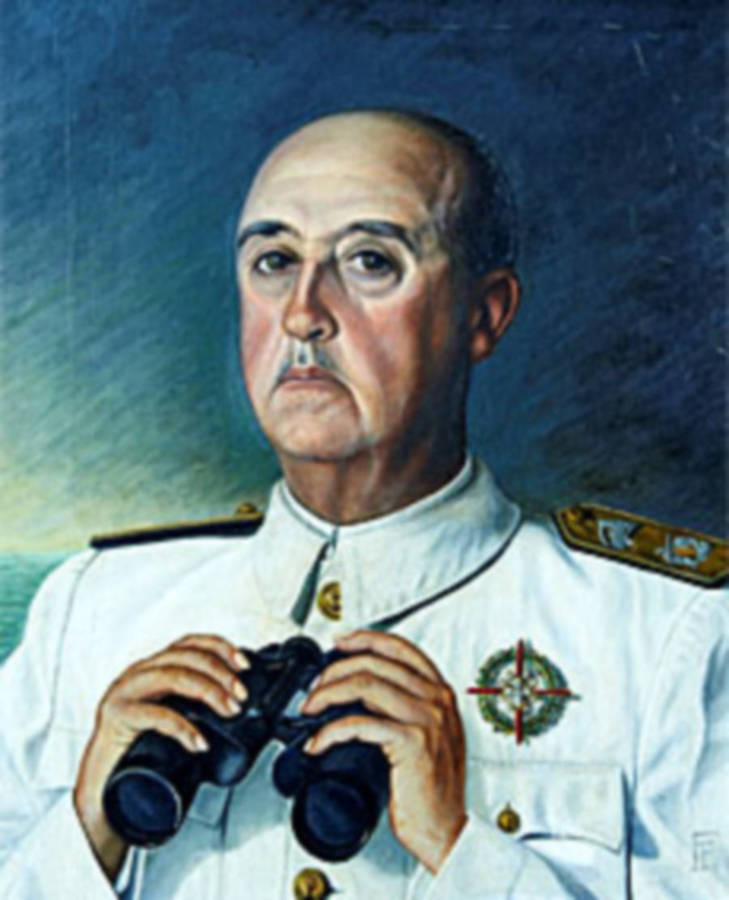

The image shows a self-portrait by general Francisco Franco.