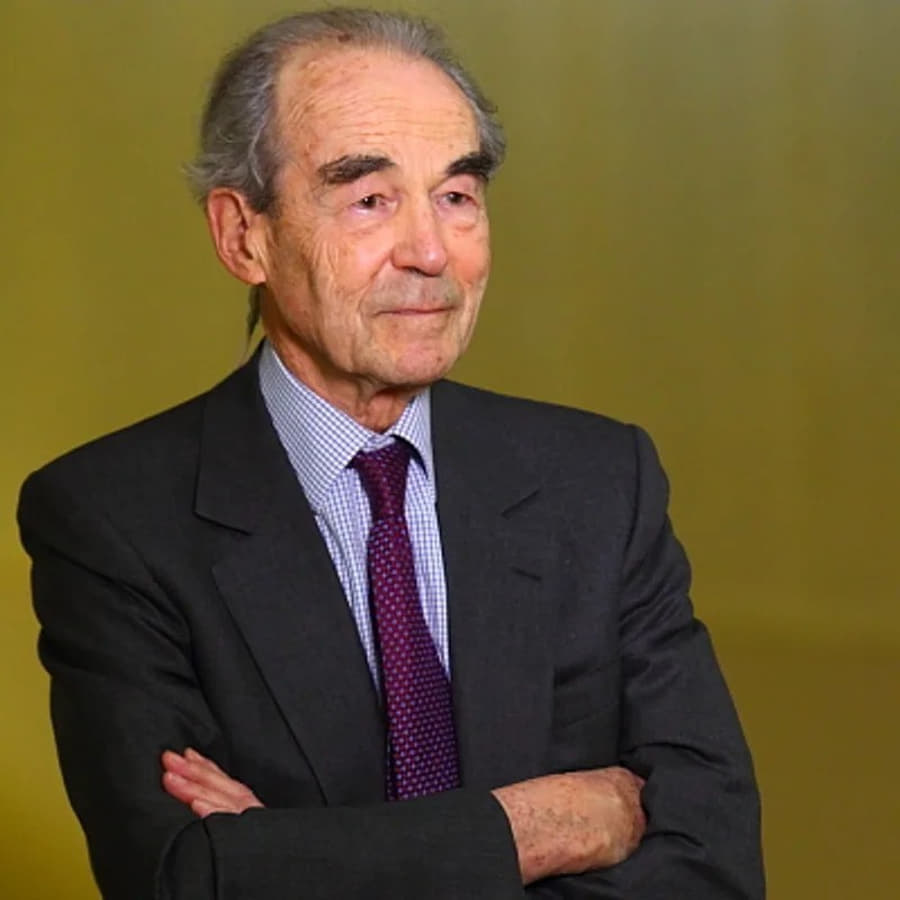

Known and recognized for his talent as a polemicist and his unquestionable erudition, Jean-François Revel added to these qualities the strength of his personal convictions against the current of his time and his country. Of his time—he defended an uncompromising liberalism against all forms of totalitarian temptation when almost no one was grumbling against the Marxist doxa. Of his country—he was an atypical exponent of a pessimistic and skeptical current in the nation that has probably deposited more militant faith in the transforming capacities of politics. However, as we shall see later, these two considerations need, if not total amendments, at least partial ones.

A Liberal of the Land who Loved Ideas

Born in Marseille in 1924, a student of the elite École Normale Supérieure and a philosophy graduate, he taught in Algeria, Mexico and Italy before abandoning teaching and devoting himself to an independent intellectual and journalistic career. He was a cosmopolitan spirit, an attitude that radiated in his writings and was reflected in his philias and phobias, but very French in an essential sense: that of the utmost fidelity to that national spirit summed up in the formula that the British historian Sudhir Hazareesingh coined for his How the French Think: “that country that loved ideas.” For, although every great nation considers itself to be an exceptional homeland, France’s particularity is that it associates that status with the genius that allows it the greatest theoretical feats and the greatest intellectual prowess. As a historian of ideas, philosopher, journalist, literary and political editorialist, director of collections in various publishing houses, Jean-François Revel’s biography fits like a glove with the epochal sense of what Michel Winock baptized as “the century of intellectuals.”

In his case, however, the slogan so often repeated in the Parisian 1960s can be reversed: unlike a whole generation seduced by that “cabal of devotees” (title of the book in which he criticized the intellectual caste infected by totalitarian ideologies), Revel preferred to be right with Aron rather than wrong with Sartre. He challenged with the weapons of the committed intellectual the kind of anti-capitalist and anti-liberal gnosticism that manifests itself in the disdain for facts and the real man. Against the prophetic attitude of his guild, which proclaims itself, as Voegelin noted, “connoisseur of the means to save the human race,” Revel dared to proclaim the nakedness of ideologies surrendered to radiant futures that pass for unwavering and sanctimonious adherence to the iron fist wielded by the salvific powers of the earth. As his boss wrote in the newspaper l’Express, Olivier Todd, he was a declared enemy of jargon, systems, gurus, social projects and utopias.

But this is, as we have already warned, only a half-truth, which leaves Revel, so to speak, on the good side of history in view of the well-known outcome of the Cold War. Because Revel’s liberalism came from the humanist left and he did not end up separating himself from a certain idea of socialism that he cultivated since his youth as a resistance fighter during the German occupation of France. He wrote his first works against the right (Lettre ouverte à la droite), against General de Gaulle and against the monarchical architecture of the Fifth Republic. He came to the conclusion that the greatest enemy of the socialism he desired was communism. He knew Mitterrand very well, and even became a candidate on his electoral lists during the long desert crossing of the socialist leader, whose political youth was, as is well known, quite different from his own (perhaps for that reason Revel was one of the first to portray that cold and impenetrable sphinx who arrived at the Elysée Palace in 1981). To put it in Oakeshott’s terms, Revel’s liberalism proceeded from the politics of faith but ended up being anchored, perhaps to his regret, in the politics of skepticism. Though never quite.

In How Democracies Perish, Revel warned that liberal democracy risks being a brief parenthesis in history, if the mental framework of Western leaders and public opinion remains a prisoner of bad conscience and political blindness. Almost naturally, and perhaps hastily, he shifted his interpretation of the red totalitarian threat to a new actor that was to replace it after the establishment of the New World Order: Islamist terrorism. This coalition of enemies explains to a large extent his bet on the American model, even though Revelian liberalism was, however, decidedly anti-Fukuyamaesque. In fact, he could rather be reproached for an excess of pessimism in his prognoses. The astuteness of reason seemed to lean toward the perverse side of history. Precisely at the moment when humanity perceived the need for a universal democracy, Revel understood that the Western democratic system “is corrupted, denaturalized, falsified at its core.” Little trace of messianism or democratic soteriology in his worldview.

An unrepentant liberal, Revel proposed in his works various remedies against democratic defeatism. This historical therapy could also be interpreted as an inner struggle against the psychological needs that the various forms of totalitarianism satisfy: overcoming nationalism, re-establishing the separation and balance of powers, matching the progress of knowledge with the efficacy of political action and decision. His theory of useless knowledge is, in this sense, symptomatic of his civilizational pessimism. The increase of knowledge in multiple fields of knowledge does not, according to Revel, have repercussions in a public space impervious to the rationalism of facts that thrives in civil society. By their attachment to the legends and prejudices of ideologies, the political-intellectual clercs continue to lead the masses along the path of chimeras.

This general attitude makes their increasingly enthusiastic defense of the United States a problematic and symptomatic element of their thinking. “If you erase anti-Americanism, you erase eighty percent of French political thought, both left and right,” he went so far as to say in an interview. This position undoubtedly reveals his public dissent. However, even he did not manage to remain aloof from the deformed image of the United States that prevails in the Hexagon.

Neither Marx nor Jesus?

For Revel America practically invented the idea of the future. While all previous societies, including modern ones, had their models in the past (the anticomania, for example, of the French revolutionaries, marvelously restored by Claude Mossé), the United States populates its imaginary with a society to come, a city on the hill to be inhabited by new men without stain. And Revel aspired precisely to a type of planetary democracy born of a second world revolution. According to the daring interpretation of Ni Marx ni Jésus [Neither Marx or Jesus], this second coming of the revolutionary spirit could only sprout by virtue of the particular historical dynamism of the United States of America, a “laboratory society” called to infect its way of life to all the countries of the world, for “revolution breaks down into two words: crisis and innovation.” It is here where one of the great errors of his understanding of historical facts can be pointed out.

Undoubtedly, he was right in understanding, perhaps before anyone else, that the revolution would not come from Moscow but from America. But, neither Marx nor Jesus? The American revolution is nothing but a particular and heterodox way of other Christians for another socialism. There is the Woke spawn to prove it, religious acrobatics, unhinged heresy of iconoclastic followers of both Marx and Jesus, twinned in the common devotion of victimocratic religion. It is no coincidence that the new European left expresses an undisguised admiration for this liberal and progressive America that fits in perfectly with its aspirations. When Revel was vituperative of the residues of totalitarian mentality in the European left despite the undeniable failures of real socialism, he was not wrong: his socialism could feel better represented in Washington. In a way, Augusto del Noce’s formula can be repeated: Marxism failed in the East because it triumphed in the West.

Edgar Morin, who by his own admission had lived his militancy in the French Communist Party during the forties and fifties of the last century as a form of religious mysticism, returned ecstatic from his stay with the “socialists” of California in the sixties. Thus he found an ideal that rejuvenated him and which he could not have defined in better terms: “Neo-Rousseauism, yearning for Christian purity, childlike warmth, libertarian tradition, utopian communism, Kathmandian rejection of the West.” Jean-Marie Domenach put it less nuanced in Esprit magazine in the 1970s, shortly after the publication of Neither Marx nor Jesus: “The United States is today the greatest communist country in the world.” Annie Kriegel recalled that communists “in their own way love America, as they feel attuned to its aspirations, its needs, the expectations that preside over the persistent use of the New World metaphor.” And he added: “Whether the entrance into the Promised Land is through migration or conversion, in both cases it has been necessary to tear oneself away from the ancient land of the Fall and Sin; it has been necessary, in person, to choose, to choose a new way of being in the world. The emigrant and the communist share the same brutal experience which is that of rupture.”

Trotsky, for his part, in a particularly revealing text, confirms this essential anthropological reality that nests in a revolutionary spirit common to modern Promethean projects: the Founding Fathers of Bolsheviks and Puritans share the same ancestors. After the Revolution, noted the creator of the Red Army, human life has become a Bivouac, that is to say, one of those camps set up provisionally to spend the night outdoors while waiting for the definitive dwelling. He wrote: “What is the use of solid houses,” the old believers of yesteryear asked, “if we are waiting for the coming of the Messiah? The Revolution does not build solid houses either; to compensate, it moves the people, crowds them in the same premises and builds barracks. Provisional barracks: such is the general aspect of its institutions. Not because it awaits the coming of the Messiah, not because it opposes his ultimate goal to the material process of organizing life, but because it strives, by constant research and experimentation, to find the best methods for building its final home. All its actions are sketches, drafts on a given theme.”

French Liberal… and American

Revel could have joined the mainstream of French liberalism, which is not that of giants like Tocqueville, but that other one portrayed by Lucien Jaume from his studies on Jacobin democracy and the 19th century. Far from enthroning the individual like the Scottish Enlightenment, French liberalism erases him. The French-style liberal individual, consecrated by the Reformation and confirmed by the Declaration of the Rights of Man, must contend with the sovereign state of the Bodinian matrix, which, far from being weakened, was strengthened by the Revolution. In figures such as François Guizot and Victor Cousin, this effort to erase the individual by submitting him to the geometric spirit of administrative centralization was manifested. French liberalism was an eminently statist liberalism, also colored with a missionary and collectivist spirit, of genuine republican civil religion. The liberalism of figures such as Madame de Staël or Benjamin Constant, supporters of the protection of individual conscience and the rights of the individual against the State, did not join the main stream of the majority liberalism in France. The Jacobin anticomania leaned to the side of the liberty of the ancients, which demands that the interest of the City should absorb the energy of all. In The Republic of the French Republicans, the interpretation of the Declaration of the Rights of Man and the Citizen was always selective. The Frenchman would only be recognized as a citizen in the capacity of soldier, taxpayer, voter or pupil of the republican school. The long shadow of Rousseau did not fade with Robespierre. French liberal humanity, beyond the universalist rhetoric, circulated along the path of a citizenship domesticated by the State. Paradoxes of French liberalism, Jaume calls them.

If we expand on this point, it is simply to point out that Revel could have perfectly followed the course of this French-style liberalism without betraying the foundations of his thought. If he did not do so, perhaps it was because Paris was no longer the Mecca of the Revolution and Moscow could not be. Washington remained as the Third Rome of socio-liberal cosmopolitanism. There was no lack of philosophical sources on which to base an American-style progressive liberalism. In fact, in the United States the liberal is, broadly speaking, a praying social democrat. This is the line of Herbert Croly, who called for the creation of a New Republic of “Jeffersonian ends with Hamiltonian means.” These are aspects that Patrick Deneen reminds us of in Why Liberalism Failed? For this new American liberalism “Democracy could no longer mean individual self-reliance based upon the freedom of individuals to act in accordance with their own wishes. Instead, it must be infused with a social and even religious set of commitments that would lead people to recognize their participation in the ‘brotherhood of mankind.'” Baptist pastor Walter Rauschenbusch deepened this sensibility by proposing a Kingdom of God on earth, a new form of democracy that would not accept human nature as it is, but move it in the direction of its improvement.” Dewey proposed a “public socialism” and Croly a “flagrant socialism,” but for both of them this socialism was at the service of the construction of a new individual freed from the bonds of the past. It is a current that reaches as far as Saul Alinsky in the 20th century, Obama’s inspiration, Robin Hood of the Chicago suburbs, friend of the Catholic philosopher Jacques Maritain (another convert, alas, to Americanism) and the subject of Hillary Clinton’s doctoral thesis.

Aron recalled in his memoirs that at the end of the 1970s Revel still considered himself a socialist, although in the paradoxical sense that “only liberalism can fulfill the hopes of socialism.” A liberal by the name of socialist, this particular vision manifested itself in a privileged way in The Totalitarian Temptation, whose first lines read: “Today’s world is evolving towards socialism. The main obstacle to socialism is not capitalism, but communism. The society of the future must be planetary, which can only be realized at the cost, if not of the disappearance of the nation-states, at least of their subordination to a world political order.” It is not forcing things too much to affirm that this bet on socialist-liberal, globalist and anti-national, de-ideologized and technocratic future-centrism makes Revel an intellectual precursor of Macronism, that is, a form of international-socialism of a Saint-Simonian cut operating behind the mask of European institutions impatient to dissolve the nation-states that founded them—institutions immersed in a federalist race that only disguises, with a kindly countenance, the true reality of the American hegemon to which they have bowed, at least since Jean Monnet. “He is not the man of the Americans,” de Gaulle said with derision about the French investment banker and “Father: of Europe, “he is a great American.”

Liberalism: A Socialism with a Human Face?

When a country subordinates its foreign policy to its domestic policy, that is to say, to the well-being of its citizens,” said Revel, “it can be considered more socialist than when it acts the other way around.” Here, at last, is the socialism with a human face so often invoked on the other side of the Wall. A socialism centered on the administration of things from which emanates the idol of material well-being. And autistic in terms of the internal concord and external security that defines the government of men. It was nothing new, in fact. It was not for nothing that Baron Hertling had already warned of this turn in contemporary politics in 1893: “It was not so long ago that word politics exclusively designated foreign policy. The respective strengths of the various states, their reciprocal relations, friendly or strained, their varying alliances, their projects and aspirations: such was the exclusive object of interest to diplomats and statesmen… Then the political interest changed direction, falling especially on questions of internal order, such as the constitution and administration of the state, brought up to date by the then so-called constitutionalism.” It is a tendency that Revel tirelessly cheered in his work, however much his pessimism made him lament, once again, the lamentable nationalist resistances of the nation-state. Socialist internationalism is perfectly expressed in this affirmation of the “liberal” Revel: “As long as the system of nation-states persists, democracy will retreat. And as long as democracy regresses, socialism cannot be established.” This socialism is nothing other than the liberal utopia of a disembodied democracy. And we can say that never has so much progress been made as in our time in this suicidal direction. Would Revel have deplored it?

The reality is that the political model of the European Union has long since veered towards a new form of liberal-socialist Welfare totalitarianism, a system, therefore, that defies Revel’s rigid antitheses: the convergence of liberal democracy and a new form of totalitarianism without violence. Did Revel forget the lessons and prophecies of the great Tocqueville about the disturbing horizon that looms over a democracy given over to paternalistic despotism? Would he have celebrated this evolution or would he have interpreted it as the fulfillment of his darkest prognoses about the inevitable infection of totalitarian ideological residues in the weak Western democracies? If so, if liberal melancholy had definitively prevailed over his socialist faith, the hypothetical Revelian analysis would resemble today the one offered to us from the post-communist East by authors such as Ryszard Legutko, who in The Demons of Democracy presents a merciless diagnosis of the European Union: the EU is today the EURSS. Contrary to what many think,” says Legutko, “the demoliberal world does not deviate too much, in important aspects, from the world dreamed by the communist man who, in spite of his enormous collective efforts, was unable to build within the communist institutions. To tell the truth, there are differences, but not so great as to be appreciated and accepted unconditionally by someone who has had first-hand experience with both systems and has passed from one to the other.” It is precisely this biographical experience that places this Polish philosopher, MEP of the conservative group, above the outdated vision of Revel, who never really suffered totalitarianism in the flesh, even though he always denounced it with vehemence and courage. Compared to this lucidity coming from the East, his judgments today seem petrified in a world that is no longer ours.

Yankee Apocalypse: The Return of Trotsky

If Revel ignored the fact that the totalitarian utopia was introduced under other guises in the mainstream of liberal democracies, his bet on the United States also overlooked a feature that John Gray masterfully exposed in Black Mass: Apocalyptic Religion and the Death of Utopia. This apocalyptic tendency of American politics was especially aggravated in the wake of the 9/11 attacks of 2001. ” In claiming a foundation in a universal ideology,” Gray asserts, “the United States belongs with states such as post-revolutionary France and the former Soviet Union, but unlike them it has been remarkably stable.”

Revel’s ideological evolution does not differ much from that of the old leftists of the Trotskyist matrix who in the United States founded the Neocon current, such as Irving Kristol, Gertrude Himmelfarb, Daniel Moynihan or Midge Decter. Michael Novak confirms: “Practically all of this group had been men and women of the left, and more specifically, of the sectors that were further to the left than the Democratic Party, perhaps among the most left-wing 2 or 3% of the American electorate. Some were economic socialists; others were political social democrats.” Gray, for his part, is very explicit about the revolutionary Marxist invoice of the thinking of this group of authors: “It is too simple to view neo-conservatives as reformulating Trotskyite theories in rightwing terms, but the habits of thought of the far Left have had a formative influence. It is not the content of Leninist theory that has been reproduced but its style of thinking. Trotsky’s theory of permanent revolution suggests existing institutions must be demolished in order to create a world without oppression. A type of catastrophic optimism, which animates much of Trotsky’s thinking, underpins the neoconservative policy of exporting democracy.” It is the policy that Revel supported in his last years, albeit in the minority of a French atmosphere very hostile to the United States and its geopolitical projects.

Like the neocons, the planetary project of disembodied democracy defended by Revel retained a utopian matrix that dispensed with the national body, presenting both (democracy and nation) almost as opposites. Revel even spoke out in favor of the humanitarian right of interference, together with Bernard Kouchner and Mario Bettati. The latter, a French jurist and professor of international law, retains his good or bad reputation thanks to his terrible apothegm, worthy of appearing in the pages of the Yankee Apocalypse: “sovereignty is the mutual guarantee of torturers.” Very bad company. It was not necessary to wait twenty years of US military occupation in Afghanistan to understand that a democracy without a body is a much more utopian project than that of a body without democracy. The return of the Taliban to power is a great lesson against the multicolored democratism of the armed missionaries and against the discourse of the beautiful souls who support it.

Sovereignty as the Origin of all Evils: The Leap towards Utopia

It is one of the great errors of Revel’s political vision, which manifests itself in his rejection of the idea of national sovereignty. To a large extent this error is explained by his typically modern conception of political concepts. He probably understood, not without reason, that the French understanding of sovereignty, which starts with Bodin’s absolute and perpetual power and culminates in Rousseau’s general will, was incompatible with the liberal society to which he aspired. But this is precisely the impasse of a certain liberalism. Instead of betting on an alternative model of popular sovereignty, such as Althusius’ medieval one, it bet on the anti-political denunciation of national sovereignty. With modern sovereignty Revel despised not only a historical concept that can (and should) be criticized but the very essence of the political, which cannot be rejected without denying reality itself. It is what is called in France jeter le baby avec l’eau du bain (throwing the baby out with the bath water). Liberalism’s distrust of political power is all the more paradoxical because liberals began by conceding everything to the Leviathan in the construction of the new man and the new society. To take back with one hand what they have given with the other: this is the uncomfortable position of the liberal soul, eternally in conflict between its anarchic pole and its macro-archic pole.

Raymond Aron, who was personally fond of Revel and who collaborated with him in their common journalistic vocation, masterfully portrayed in his memoirs the aporias of his thought: “What impressed me in him as a writer was the simultaneous presence of an authentic culture and the art of making the polemic comprehensible to all readers. His books, which simplified without vulgarizing the great debates, were inspired by an anti-communism that he himself described as ‘visceral’ and found a large audience on both sides of the Atlantic, which demonstrated his success in such a difficult genre. At the same time, I was cross—and I told him so when our relations became closer—at his insistence on calling himself a ‘socialist’, of the leap he was taking towards utopia by rising up against national sovereignties, in his opinion the evil par excellence, the origin of all evils.” Once again, there is in Revel a skepticism that does not get off the ground, a utopia that refuses to die.

Indeed, Revel had written in The Totalitarian Temptation that Maurras had triumphed and Marx had failed. A puzzling judgment: with the principle of national sovereignty and the cult of the nation associated with the State, the principles of absolute monarchy were clandestinely triumphing in the modern world. This partly explains the anti-Gaullist origin of his intellectual career and his support for Mitterrand. His first works, Le style du général [The General’s Style] and L’absolutisme inefficace [The Inadequacies of Absolutism], fired their argumentative ammunition against General de Gaulle and the monarchical architecture of the Fifth Republic. As an interpreter of the genealogy of ideas he was not without reason but, in this respect at least, he failed to see that in contesting the Gaullian enterprise against the incipient Europeanist federalism and the military hegemony of NATO he was siding with another totalitarian temptation, a temptation perhaps more subtle but ultimately also more effective than that embodied by the Soviets.

In the 1980s, with the reprinting of his book against de Gaulle, he did not renounce his judgments against the general and what he considered as historical errors of his interpretation, but he ended significantly with these words: “De Gaulle was great, not because he was infallible, but because he was capable of that speed of decision and action which is the only mark of true leaders, and which allows us to say that, had they not been there, better or worse, the world would in any case have been different. Of how many can the same be said?” Had he finally understood that the greatness of the great stylists of politics ends up being in the end indispensable to sustain, not only democracy but also the prosperity of free peoples? We do not know what Revel would have said or written about the course of events between his death in 2006 and today. But perhaps this sentence pointed in a more stimulating direction than the one he reflected in previous writings.

Carlo Gambescia has masterfully portrayed in Liberalismo triste the features of a realistic liberal tradition, sentinel of the facts and attached to the regularities of politics. It is a melancholic tradition that knows well, as Berlin pointed out, that “from the twisted wood from which man is made… nothing entirely straight can emerge.” This sad liberalism has its feet firmly on the ground and feels awkward trying to lift them off. “It is melancholy proud in Burke; benevolent in Tocqueville; Faustian in Weber; aloof, perhaps too much so, in Pareto; restless, notwithstanding scientific habit, in Mosca; reasoning in Ortega; feverish in Röpke, methodical in Jouvenel; serene in Aron; humble in Freund; autoironic in Berlin.”

There are no willows in Revelian melancholy to inhabit this Olympus of thought. His vision did not entirely expurgate the utopias which, on this or the other side of the Atlantic, imagined “new heaven and a new earth” for men. He did not become a true sad liberal. Fortunately, he was not a sad liberal either. Let’s keep that.

Domingo González Hernández holds a PhD in political philosophy from the Complutense University of Madrid. He is a professor at the University of Murcia. His recent book is René Girard, maestro cristiano de la sospecha (René Girard, Christian Teacher of Suspicion) He is also the Director of the podcast “La Caverna de Platón” for the newspaper La Razón. He has explored the political possibilities of Girardian mimetic theory in more than twenty studies and academic papers. His latest publication is “La monarquía sagrada y el origen de lo político: una hipótesis farmacológica” (“Sacred monarchy and the origin of politics: a pharmacological hypothesis”), Xiphias Gladius, 2020. This article appears through the kind courteesy of La gaceta de la Iberosfera.