The question of the “home of origin” (Urheimat, Homeland) of the Indo-Europeans has given rise to the most varied hypotheses and suppositions, theories that are analyzed in detail in Alain de Benoist’s book Indo-Europeans: In Search of the Homeland, without the author—nor anyone else—being able to venture a definitive solution, even though the new revelations of paleogenetics point to the “Yamna culture” of the Eurasian steppes, since anthropological and archaeological evidence insistently points to the European Nordic area. In any case, the debate about the “original homeland” of the Indo-Europeans is still open.

5,000 years ago (especially in the period 2800/2500 BC. ), in the Bronze Age, it seems that a people from the Eurasian Pontic steppes, predominantly light pigmented (skin, eyes and hair), nomadic herders and herdsmen, predatory warriors mounted on horseback and with wheeled chariots, used for both transport and combat, with unique funeral rites, innovative metallurgy and unique pottery, began to invade Europe, in successive migratory waves, imposing themselves on the peaceful hunter-gatherer-farmers. In any case, around 2000 B.C., the hardy bands of steppe nomads reached the Atlantic coasts and passed to the British Isles, after a frenetic race of invasion and conquest, devastating in their path the primitive, agricultural, peaceful, matriarchal and egalitarian European pre-civilization cultures.

Their “original habitat”: the steppes of southern Russia and Ukraine, between the Black and Caspian Seas, reaching westward to eastern Hungary across the Balkans, and eastward to present-day Kazakhstan and the Altai, which would validate the hypothesis of the “kurgans” (tombs in the form of burial mounds) of Lithuanian-American archaeologist Marija Gimbutas. Her greatest “legacy”: the impressive extension of the Indo-European languages, which include most of the languages spoken from Iceland and Ireland to northern India, in addition to the Indo-European peripheries in America, Australia and South Africa. This “Pontic and Steppe hypothesis” seemed to disprove the “Nordic or Germanic hypothesis” held, among others, by Gustaf Kossinna (and more recently, by Lothar Kilian and Carl-Heinz Boettcher), which fits better with the prehistoric data of mythology and anthropology, but which fell out of favor because of the perverse use of “Aryans” in Nazi Germany. Their “other legacy”: genetic inheritance.

They were the “Yamnayas,” the proto-Indo-Europeans who colonized all of Europe, Central Asia, reaching the southern Caucasus, Iran, Afghanistan, Pakistan, India and Chinese Turkestan. The “Yamna” culture (“hole” in Russian and Ukrainian, referring to the graves where they buried their dead) are a “ghost people,” as it is known in genetics, a people that have disappeared but can be identified by the genetic, archaeological, linguistic and anthropological traces they has left in their wake. The result is that the genes of the Yamnayas are present, to a greater or lesser extent, in all present-day Europeans.

Thus, paleogenetic research led particularly by the American geneticist David Reich—carried out from 2010 and culminating in 2015—concludes that “today the peoples of western Eurasia (the immense region encompassing Europe, the Near East and much of Central Asia) show a great genetic similarity… Western Eurasia reveals itself to be homogeneous, from the Atlantic façade of Europe to the steppes of Central Asia (Who We Are and How We Got Here: Ancient DNA and the New Science of the Human Past). Genetic haplogroups R1a and R1b, transmitted through the paternal line, are the most representative of present-day Europeans, with a predominance of the former in the East and the latter in the West. Precisely, these two branches are directly linked to the Yamnaya ancestors. Thus, around 2500/2000 B.C., according to the data provided by ancient DNA, the “norcaucasian” or “steppic” component was already part of the anthropological heritage of most of the inhabitants of Europe.

It should be noted that, in fact, archaeological, linguistic and mythological disciplines already indicated that the close kinship between the Indo-European languages meant that they all derive from a single original language (Ursprache), which had been spoken by a single people (Urvolk) in a very ancient homeland (Urheimat), to be spread later, in the course of a series of migrations. Thus, the spread of Indo-European languages would represent the expression of a people living in the same geographical area, in a community of culture and civilization, sharing expressions related to flora, fauna, economy and religion. Now, paleogenetics has confirmed this hypothesis.

But how could this rapid migration/expansion have occurred in a people presumably few in number? In the first place, this “rapidity” must be qualified without taking into account the context of war, since according to the researcher Wolfang Haak, the “conquest” of such an immense territory could have taken about 500 years.

Secondly, the explanatory factors of this prehistoric proto-Indo-European “great march” are diverse. The eminently warlike character of the Yamnayas, with an overwhelming superiority in the mastery of metallurgy, reflected in the use of weapons, such as the sword, the dagger, the bow and the battle axe, their extreme mobility through the use of the horse and wheeled chariots, as well as a society structured very hierarchically around a group of men who held supreme leadership of the various clans and tribal families, to which should be added, according to Kristian Kristiansen, a greater anthropological complexion, more corpulence; in short, surely due to a better diet, because compared to a diet basically reduced to cereals and vegetables typical of the Paleo-Europeans, the Yamnayas enjoyed a more caloric diet based also on meat and dairy products. The conquest/invasion was the work, above all, of young men (according to chromosomal sequences, between 5 and 15 men for each woman), of “bands” not very numerous, but very active militarily and sexually, because they had great reproductive success, surely because they enjoyed advantages in the competition for female partners, occupying the summit of symbolic, religious, political, military and social power.

In any case, although the genetic findings attribute a central weight to the Yamnayas in the spread of the Indo-European languages, which tips the balance definitely in favor of some variant of the “steppe hypothesis”, these discoveries do not yet resolve the question of the territory of origin of the Indo-European languages—acknowledges Reich—the place where these languages were spoken before the spectacular Yamnaya expansion. The debate about the “original homeland” of the Indo-Europeans, therefore, remains open.

Despite the tremendous sensation caused by the paleogenetic studies, which revealed the massive migration of the peoples of the Yamnaya steppe culture in the Early Bronze Age to northern, central and western Europe, considering this event as the basis for the spread of the Indo-European languages, other authors are beginning to express their criticism of the genetic inference and, in particular, its implications for the problem of the origins of the Indo-European languages.

According to the genetic revelations, the steppe “Yamna culture” would be associated with the Proto-Indo-European language, while the origin of the derived linguistic groups (Greek, Germanic, Italic, Slavic, Celtic, Baltic, among others) would be attributed to the cultures of the “Chordate pottery” (also called “battle-axe culture,” spread in northern and northeastern Europe). The supporters of this hypothesis, however, are aware of the relative weakness of their conclusions, advancing, for example, that perhaps not all Indo-European peoples come from the Yamnaya, but only some of them. This means, in essence, that we are not dealing then with the cradle of the proto-Indo-European, but only with one of its subfamilies: in this case, the stereopic hypothesis of the origin of the Indo-Europeans would be transformed only into the origin, so to speak, of the Indo-Iranian group.

Many archaeologists doubt that the discoveries in question reflect a direct migration from the “Yamna culture” to the “Chordate culture.” The first doubt is that the Yamnaya people spoke the Proto-Indo-European language. All recognized dates for the fragmentation of the Proto-Indo-European language are between the seventh and fifth millennia BC. The Yamnaya culture is well dated by calibrated radiocarbon chronology: it begins, at the earliest, within the second third of the third millennium BC. Thus, there is a gap of about 2.5 millennia (1.6 millennia minimum).

The Russian archaeologist Leo S. Klejn highlighted a remarkable fact: the strange distribution of steppe genetic contributions to the “Corded Pottery” cultures and their descendants, revealed by Haak and others, very rich in northern Europe and increasingly weaker towards the south, particularly in Hungary, just where the western edge of the “Yamna culture” itself is located. This distribution is at odds with the suggestion that the source of the contribution to the “Corded Pottery” cultures is the southeastern “Yamna culture;” that very distribution seems rather more natural, if it is suggested that the common source (of both cultural units) is in northern Europe—and hence the common cause of genetic similarity.

The mystery of the origin of the Proto-Indo-Europeans remains an enigma, but perhaps not so indecipherable after reading this book.

Jesús Sebastián Lorente is a Spanish lawyer. This article appears through the kind courtesy of Elmanifesto.

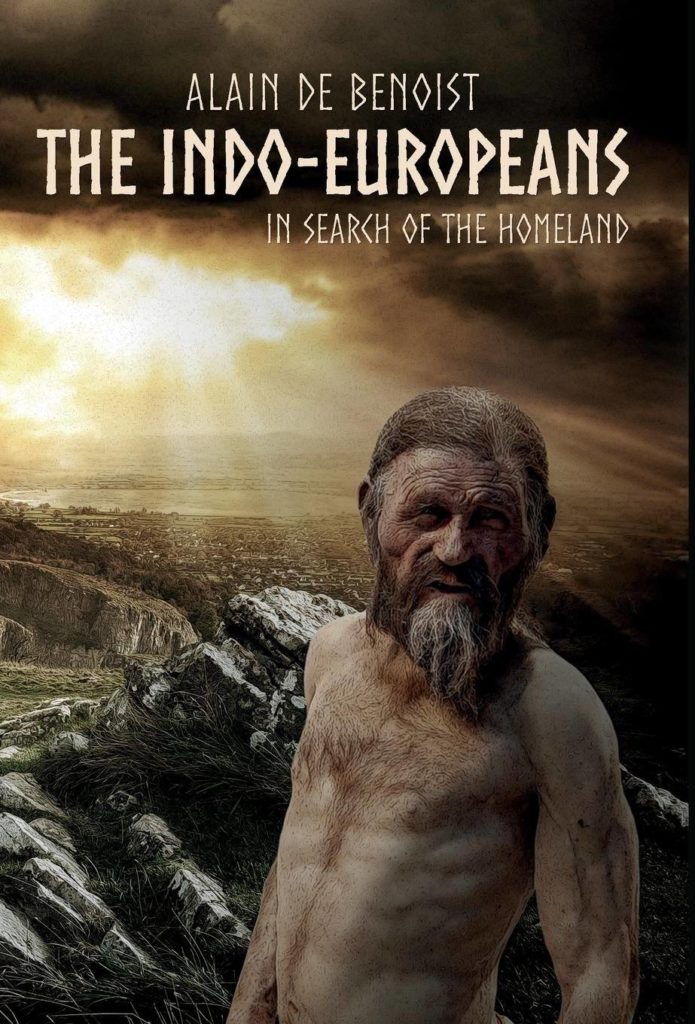

Featured image: “Trizna,” by Andrey Shishkin, painted in 2019.