“I disapprove of what you say, but I will defend to the death your right to say it.” No, Voltaire didn’t write this (it was one, Evelyn Hall), but it sums up what I regard as the quintessence of liberalism.

Till maybe 25 years ago, I was perfectly happy being called a classic liberal and many people did so. It meant being at ease with yourself and yet not complacent – an enemy of injustice and a believer in the rule of law. All too often the latter has been travestied by the so-called liberals of today as being “law and order,” “lock up the crims,” etc. Only it doesn’t mean that at all. It means a belief in the law, essential to any civilised nation state, and a belief in the equality of all to the access and due process of law. A noble, liberal idea.

I use the word “travesty,” and sadly it applies to all too many so-called liberals of today: liberalism has become confused with, and almost inextricably entangled with, a kind of leftism that would disavow Evelyn Scott’s statement. With it comes an exponential increase in cancel culture, in “no platform,” and in vehement opposition to “your right to say it” if “it” is equated with hate speech.

No, liberalism should be all about learning from opinions different than yours and being ready to modify them in the process. For me a moment of epiphany was when I took on the thankless task of lead speaker defending Edward Heath’s failing government in a high school debate. I was no Tory (and I’m still not) but I found myself writing, “Capitalism is surely the least worst system we’ve got. It has its weaknesses, even its evils. But to his credit Mr Heath is aware of these and has pitted himself against what he calls, ‘The unpleasant and unacceptable face of capitalism.’ He wants to reform it, not overthrow it.”

I lost heavily – partly because one Jeremy Black was in brilliant form on the other side (and he personally supported Heath). I was dog-tucker, as we say in Australasia, but I had learnt a lot by putting myself in the government’s shoes.

I was aided and abetted in my speech by my father, who realised late in life that his mistake was to have had too much faith in essentially illiberal Marxism and too little in fighting – to repeat Heath’s phrase – “the unpleasant and unacceptable face of capitalism.” Liberalism ultimately overcame socialism for him, even though it took a lifetime.

A question: do you think we can have a debate with the decency and at the same time the robust intelligence, on the same theme, at any high school today?

Traditional liberalism has always run the risk of looking feeble, flaccid and wishy-washy. We are the “best people” who seem to “lack all conviction” to the extremists around us. Liberalism’s belief in respecting the constitution, law and institutions like the monarchy, parliament and the church (yet enjoying constructive criticism of them) can mean that it is prone to gradualism – which is only one step away from the ‘masterly inactivity’ practised as a fine art by the British politician A.J. Balfour.

But that reading of liberalism ignores the “defend to death” element of Scott’s quotation and its vehement opposition to injustice and extremism – circumstances in which liberals may risk being momentarily illiberal without losing sight of the big picture.

Historically, I know I would have been a Girondist in the French Revolution, a Parliamentary Reformer in 1832 (sorry, Professor Clark), a Dreyfusard, a Menshevik in 1917, a civil rights and anti-apartheid marcher back in the 1960s – oh, and add to the mix being pro National Health Service and Prague Spring.

Probably the last great political liberal was Roy Jenkins (d. 2003), a pioneering Home Secretary in the 1960s, as well as a distinguished Chancellor of the Exchequer, upholding capitalism in difficult times. His last great work was a biography of Churchill, never an easy fit in the Liberal Party (nor indeed the Conservatives, who think they understand him but don’t); considerably to the right of Jenkins in many ways, and today a target for mindless defacers of his statue outside parliament. Jenkins’s unequivocal verdict? The greatest British prime minister of the 20th century.

Roy Jenkins, where are you when we need you? And, I ask in the same breath, oh Guardian, Guardian, what crimes of journalism and fake news have in the last 20 years been committed in your name? Why have you stopped publishing my letters and why do all your journalists ignore me when I factually correct them? I lament for liberalism.

Zbigniew Janowski, who commissioned this essay, has tried his damnedest to work on this and purge my threatened, and probably by most people’s definition, vestigial liberalism. I commend his vigour in doing so – but he won’t ever quite succeed. This is because liberalism is a thing I cling on to.

We classic liberals are the hardest to convert to socialism (perish the thought), but equally to conservatism. Our religious equivalent is agnosticism; and anyone can tell you it’s far easier to convert an atheist into a true believer – or the reverse. We would have lasted for about 5 minutes under Stalin, Pol Pot or the Chief Executive of the Museum of New Zealand in the late 1990s. We are the easiest and softest targets of “passionate intensity” to quote Yeats. And yet we’re quietly proud of who we are and what, as a threatened species, we stand for.

Mark

Mark Stocker is an art hiostoran who writes books and articles on Victorian public monuments, numismatics and New Zealand art.

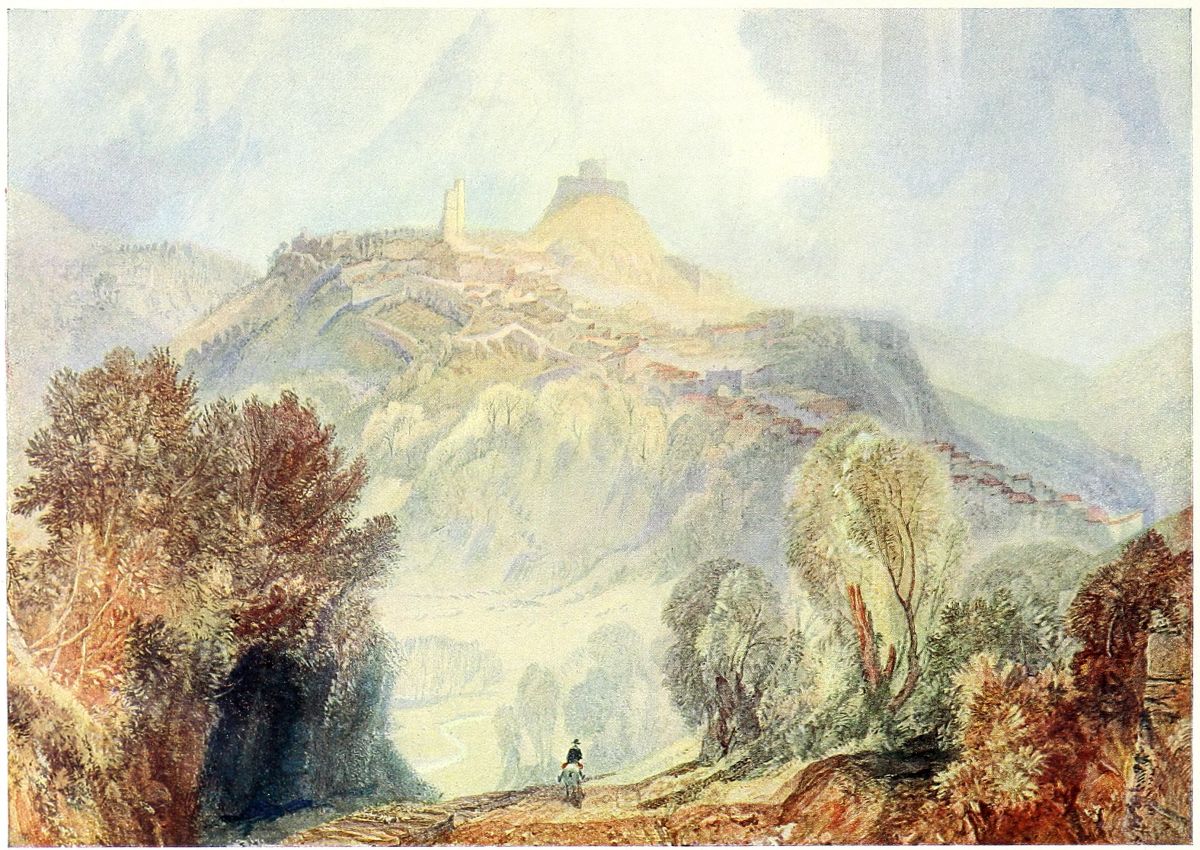

The featured image shows, “Launceston, Cornwall,” by JMW Turner; painted ca. 1814-1827.