Every time we have had the opportunity to speak about metapolitics, we have argued that it is interdisciplinary, where other disciplines such as literature, economics, philosophy, theology, history and politics converge in an attempt to explain the major categories that condition the political action of current rulers.

Although there are at least three interpretative currents—those who pretend to make metapolitics without politics, those who limit it to the recovery of public policy and those who interpret it as a metaphysics of politics—all agree on the method: to go to the things themselves and describe them as accurately as possible.

The method is therefore phenomenological in its two aspects: eidetic or essential description and hermeneutic or interpretative.

However, metapolitics and its proponents have developed their own mode of exposition, which we call, festina lente, that is, to hasten calmly, or to be hasty with circumspection, offering quick, prompt answers to the problems that are presented to us but with maximum prudence, sine ira et studio. It is necessary to publish quickly, even fragmentarily, the result of the research (festina), waiting for the intersubjective verification of others, to bring about rectification, clarification or compliment of what has been researched. Today, we are in the age of the Internet and so we have to take advantage of it.

What happened with metapolitics, mutatis mutandi, is what happened with the historical (what is said about history) and historiography in the last half of the 19th century. Humboldt, Dilthey, Droysen and so many others wanted to provide studies of the historical with an agency analogous to that which Kant in his Critique of Pure Reason offered to the physical and natural sciences.

Thus, Droysen states that the method of history is forschend zu verstehen, to understand by inquiring. The difference between scholars of history—according to J.G. Droysen, the philological—and historiography or the historical is that the former is concerned with authentic documents or the chronology of the events of the Lutheran Reformation, while the latter looks into the cognitive orientation and meaning of these documents. The former leads to the preparation of knowledge, while the latter to knowledge itself.

The scholar does not get involved in the human drama he studies, because he lives the placid and restful life of the scholar who has his salary assured month after month. The one who is involved is the one who seeks knowledge itself. The one who wonders about the being of the being of the entity, as Heidegger says. For the meaning of what is.

With metapolitics something analogous occurs; for while the political scientist wonders about the political activity of parties and agents, the one who seeks to do metapolitics wonders about the meaning of these actions—where they come from and where they are going; what are their constraints and what are their freedoms. His method, as we said, is the phenomenological method of dissident hermeneutics whose mode of exposition is the festina lente, to hasten calmly.

As we can see, there is a very close proximity between hastening calmly and understanding by inquiring. But the difference is that the festina lente incorporates the novelty of the Internet by making available to others the concepts to be studied and awaits their answers or verifications in the enrichment of the concepts treated.

In this sense, I am tempted to say that metapolitics finds a very great contemporary ally in historiographic production, both hermeneutic and conceptual; hence authors such as Hans Gadamer and Reinhart Koselleck are recommended reading for the discipline.

We must not forget what Epictetus of old said: “It is not so much the facts that move man, but rather the words about those facts.”

This does not mean, as Nietzsche exaggerated, that there are no facts but only interpretations. No, there are facts that, depending on how we describe them, through political correctness or unique thought, or through the thought police, will produce in the subject’s conscience a preconceived or predetermined reaction by the producers of meaning: basically, the mass media. But there is also another possibility, which consists in working those facts and the concepts that produced those facts, through metapolitics, with the aim of achieving an awakened and incorruptible conscience.

Addendum

There are different types of hermeneutics—existential, analogical, ontological, discursive, language, classical, etc., so we can justify our proposal of a dissident hermeneutics to address studies on metapolitics. We say “dissident” because we start from dissent as a method of metapolitics, according to which we seek another meaning to the social-political disorder we suffer. Its motto could be, opposer pour penser.

Dissident hermeneutics rescues the existential dimension of the interpreter, who starts from the interpreter, who starts from the preference of himself and his situation in a given ecumene of the world. That is to say, there is no universality, as in Kant-Habermas-Apel, in understanding, since it is done from a genius loci. And it is dissident because, first of all, it dissents with the status quo in force and its great categories that condition political action, offering another sense.

Thus, the approach to these major categories is based on dissidence from them because they are products of crypto-politics and not of public policy. All the mega-categories that make up this globalized world are products and creations of the different lobbies or power groups that exist in the world and that end up governing it. Dissident hermeneutics starts from this presupposition but, at the same time, its criterion of truth is based, no longer on the ideologues of different sorts, but on the different ethos of the ecumenes that make up this world, which is a cosmos, meaning both order and beauty. The world, in its ultimate sense, is an ordered and beautiful set of entities that compose it—in such a way that when man disarranges it, it is transformed into something ugly and unlivable.

Alberto Buela is an Argentinian philosopher and professor at National Technological University and the University of Barcelona. He is the author of many books and articles. His website is here.

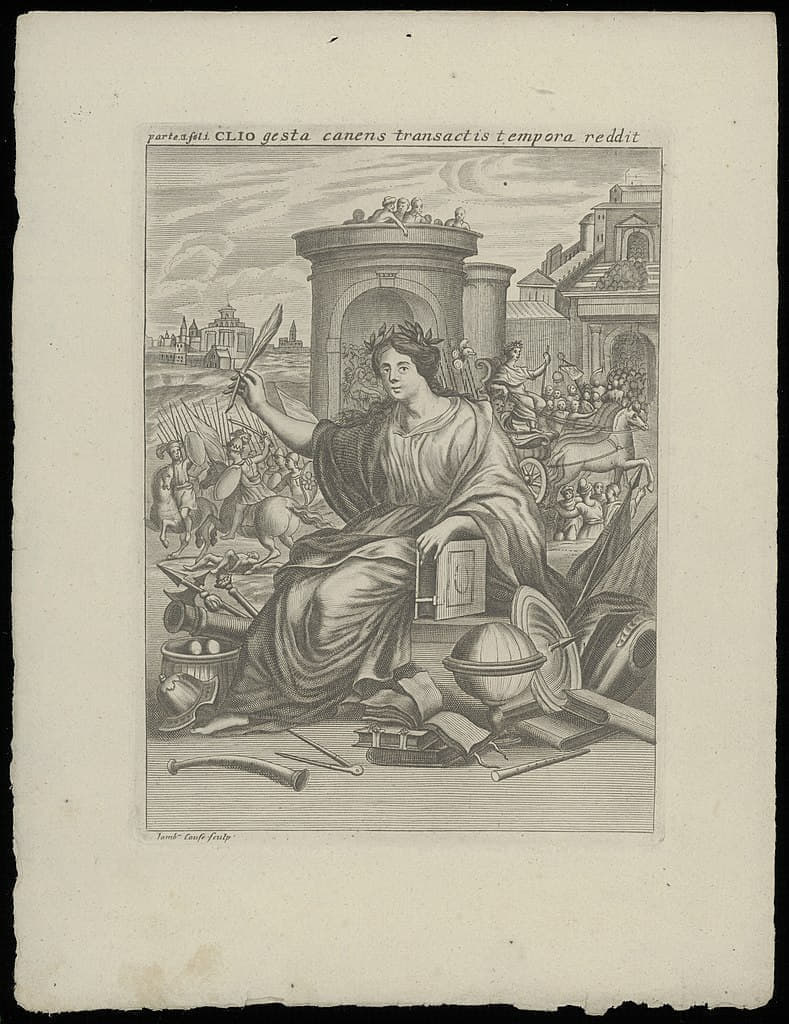

Featured: Clio, by Lambert Cause. Print, ca. 1600. The caption reads: “Clio gesta canens transactis tempora reddit” (Clio, singing of famous deeds, restores times past to life), which is the opening line of Ausonius’s poem, “Nomina musarum” (“Names of the Muses”).