Falk Horst, the admirer of the socio-political thinker Panajotis Kondylis (1943-1998), published a substantial anthology a few months ago, entitled, Panajotis Kondylis und die Metamorphosen der Gesellschaft (Panajotis Kondylis and the Metamorphoses of Society).

Characteristic of the work of the late Greek scholar, who spent a large part of his life in Heidelberg and who mostly carried out his conceptual drafts in German, was his interpretative starting point based on claims to power. In contrast to other historians of ideas and social affairs, who are inclined to moralize, Kondylis never fought for the “good.” Although influenced by the Enlightenment, his editor, Falk Horst, is right when he speaks of a philosopher of the Enlightenment without a mission.

Kondylis dissected successive world views based on the Middle Ages; but he undertook his task as impartially as possible. He called this approach “descriptive decisionism,” which he differentiated from value-based understandings of human decisions and claims. And he called the scientific approach, which he pursued in his mature works, as “social ontology.”

First and Foremost A Social Being

Kondylis starts from the basic assumption that the human being cannot be separated from a certain social relationship. From his point of view, man is primarily a social being, whose relationship to fellow human beings and to the world outside must be taken into account through his position in a given hierarchy.

First and foremost, one takes care of self-preservation, which requires the cooperation of others, and then of defending one’s niche against opponents. In his small volume, Macht und Entscheidung Die Herausbildung der Weltbilder und die Wertfrage (The Formation of World Views and the Question of Value [1984]), Kondylis focuses on the combative and power-striving side of interpersonal interactions.

Moralism or Nihilism

Fundamental to his lengthy books on the Enlightenment, classical conservatism and the age of world politics is his use of a power-oriented perspective of interpretation. Even with scholarly disputes and strictly developed theoretical work, a fighting spirit that shapes all concerns can be discerned. The scientist sets his thesis against that of his opponent.

The Enlightenment thinkers set out to assert nature and sensuality against a medieval way of thinking. But the former participants went their separate ways when the question arose whether the struggle against the rejected metaphysics should result in a normative morality or in a nihilism that decomposes everything. The Enlightenment thinkers, the advocates of a rational morality like Kant and Voltaire, and nihilistic materialists like Holbach and La Mettrie, split into two opposing groups of thought.

The bourgeois society, which upheld the cultural world of the Enlightenment, had to wage a two-front war against conservatism, which wanted to reassert the ideals of a premodern social order, and against mass democracy, which advocates the equality and exchangeability of the crowd. Without considering this dialectical, militant thrust, Kondylis believes, successive ruling classes and leading ideologies can hardly be understood. Only with regard to a counterpart does the individual develop collectively, as being-like and abstract.

A Synthesis of Marx And Carl Schmitt?

Kondylis’ social ontology and anthropology is usually interpreted as an imaginative amalgamation of the thought of Marx and Carl Schmitt. It may be astonishing that Kondylis recognized Marx, but far less Schmitt, as a pioneer. He also generously admitted as influences in his world of ideas both Reinhart Koselleck, with whom he had a long-term correspondence, and his doctoral supervisor from Heidelberg, Werner Conze. He also mentioned Spinoza, whose theological and political treatise helped shape his concept of power.

But why did Kondylis treat Schmitt, whose friend-foe thinking he shares, almost neglectfully? It may be that Kondylis wanted to emphasize the originality of his terms. Just as relevant, as Horst’s anthology makes clear, Kondylis was radicalized in his youth when he had protested against the Junta of the colonels in his Greek homeland.

The Marxist character can be traced back to these youthful years, even if the mature thinker could hardly be classified as a Marxist or as a leftist. The focus on the course of history and socially determined major cultures point back to a Marxist-inspired focus. It is clear, however, that Kondylis like Koselleck and other leading German historians of ideas from the second half of the last century, was influenced by Schmitt.

The fact that Kondylis handled a single-track or overly simplistic view of the world is a common criticism of his anthropological and political perspective, which revolves around self-preservation and striving for power of the socially settled individual. But that presupposes that the social researcher Kondylis wanted to provide an overall picture of political, community and ideological action. Instead, his ideas can be used to shed light on human behavior and to provide insight into human motivation in individual situations.

Not An Optimist

For all his devotion to the Enlightenment and the associated insights, Kondylis by no means represented the optimistic view of the future which shaped eighteenth-century rationalism. He belonged to the group that Zeev Sternhell and Isaiah Berlin characterized as “les Contre-lumières,” and which were supposedly up to no good. These brooders used the critical approach of the Enlightenment to question and even devalue their final vision.

In other words: Kondylis understood his teaching assignment differently than the moralists he mocked. Apart from the decision-making of socially located and motivated individuals and groups, who act in the area of conflict, with other similarly determined beings, Kondylis cannot offer us a world-picture or a vision of the future. To his credit, he warns against those whitewashers who want to abolish our freedom and our sobriety.

Paul Gottfried, Ph.D., is the Raffensperger Professor Emeritus of Humanities at Elizabethtown College (PA) and a Guggenheim recipient. He is the author of numerous articles and 15 books, including, Antifascism: Course of a Crusade (forthcoming), Revisions and Dissents, Fascism: The Career of a Concept, War and Democracy, Leo Strauss and the Conservative Movement in America, Encounters: My Life with Nixon, Marcuse, and Other Friends and Teachers, Conservatism in America: Making Sense of the American Right, The Strange Death of Marxism: The European Left in the New Millennium, Multiculturalism and the Politics of Guilt: Towards A Secular Theocracy, and After Liberalism: Mass Democracy in the Managerial State. Last year he edited an anthology of essays, The Vanishing Tradition, which treats critically the present American conservative movement.

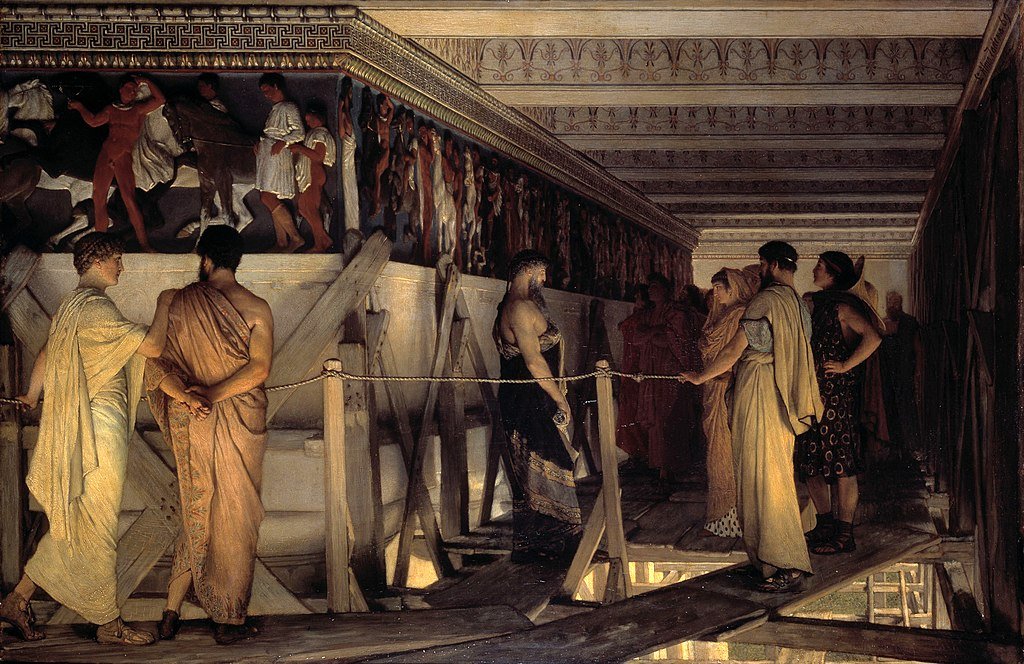

The image shows, “Phidias Showing the Frieze of the Parthenon to his Friends,” by Lawrence Alma-Tadema, painted in 1868.

Courtesy Blaue Narzisse. The German version translated by N. Dass.