By a twist of fate, our eulogy of Professor Paul Cantor was first drafted shortly after the death of Elizabeth II. [Note: This article assesses Mr. Cantor’s contribution to Shakespearean scholarship—it is not an endorsement of his politics].

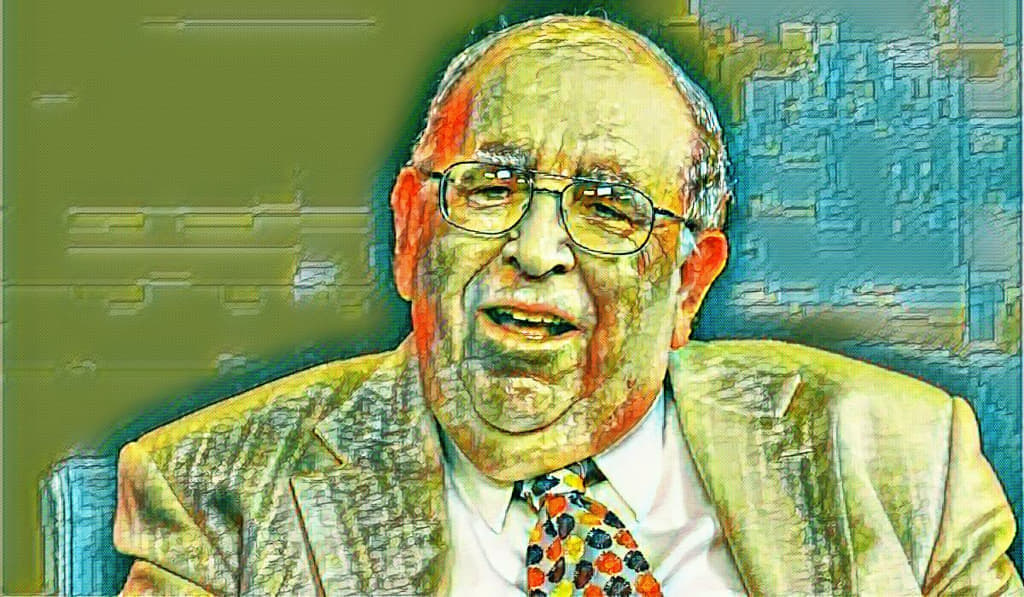

Struck down by the same malady which killed Paul Cantor, only now have I learnt of his death. Professor of English Literature at the University of Virginia and guest Professor at Harvard’s John F. Kennedy School of Government, he died in February 2022 at the age of 76, having devoted his life to teaching Shakespeare.

Here is our first enigma: for 45 years and to over ten thousand students, Cantor taught a Shakespeare and Politics seminar, erudite and above all, thought-provoking. That notwithstanding, he was greeted with stony silence in Europe and even in England. Not once, saving error, was he engaged as consultant to a history play, not once was he invited to speak before a European scholarly society.

Through all those years, Cantor’s international contacts were restricted, if that is the word, to hundreds of telephone and e-mail exchanges with foreign students, including students from the PR of China. What could possibly explain the void in academe?

As it happens, Paul Cantor lived a double-life: one as a neo-conservative ideologue in economic matters, a friend to avowed war-mongers such as William Kristol. Apologist to Ludwig von Mises and Friedrich von Hayek, Cantor espoused the Austrian School of Economics, notorious for players like Milton Friedman or Margaret Thatcher, who would have wreaked rather less harm in vaudeville.

That said, Cantor’s role in that côterie was rather that of the Court Fool, whom he much resembled physically. Short, well-padded and ever-jolly, Cantor spoke with a thick Brooklyn accent and wore his coat-sleeves dangling to the fingertips. Hardly the image projected by notable Shakespeareans such as Jonathan Bate, now Sir Jonathan—tall, slender, elegant, with thoughts as gracefully policed as their every gesture.

Court Fool, perhaps. But another enigma: how did a scholar and polymath of such calibre (at Harvard, he nearly opted to study astronomy), take up with a clique of the gimlet-eyed fanatics who lie behind every major US policy disaster since Dallas, November 22, 1963?

Scroll back the decades.

Paul Cantor’s birth-year was 1945, the year of the US atomic firestorm at Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

Meanwhile, in a New York putatively at peace, the child Cantor had access to his father’s and grand-father’s large private libraries. Very evidently a victim neither of material nor cultural deprivation, Cantor’s childhood and teenage years were nevertheless marked by two other firestorms sowing fear amongst American Jews, of whom many had recently fled Germany or Eastern Europe: the execution of Julius and Ethel Rosenberg for espionage in 1953, and the allegedly “anti-Communist” terror campaign (circa 1949-1955), spear-headed by Sen. Joseph McCarthy and HUAC, the House Un-American Activities Committee. The targets were “Communists,” or “homosexuals”—whether real or imagined is irrelevant—largely Jewish intellectuals from the East Coast, theatre people and Hollywood script-writers, as well as leading academics and State Department career diplomats; what that motley crew had in common was opposition to the Doctor Strangeloves of this world.

The elephant in the room in Cantor’s youth was thus the hell unleashed by HUAC; its figure-head was a drug-addict and doubtless blackmail victim, Senator Joseph McCarthy, whose substances for abuse are now known to have been procured by the head of the Federal Bureau of Narcotics.

HUAC’s hearings in the US Senate led to suicides, countless dismissals, and exile for some of the country’s most remarkable citizens. Amongst HUAC’s celebrated victims one finds the actor and producer Sam Wanamaker (Wattenmacher in Yiddish), who left for London with his family and never returned; it was Wanamaker who had the Globe Theatre, of which Shakespeare had been shareholder, rebuilt on Bankside. Another victim was Jerome (Rabinowitz) Robbins, dancer and choreographer of West Side Story. Crumbling under the pressure, Robbins denounced to HUAC a string of real (?) or make-believe (?) “Communists” among his fellow artists, with disastrous results.

From a press release by a HUAC victim, the blacklisted Shakespearean actor Morris Carnovsky, one gets a whiff of the pornography of violence that typifies HUAC: “an inquisition into the inviolable areas of one’s deepest manhood and integrity—the end result is the blacklist, the deprivation by innuendo of one’s right to life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness in work. And here we have what the black opera singer and actor Paul Robeson threw back at HUAC.

As it happens, Paul Cantor knew Carnovsky well, of whom he recalls: “at the then flourishing American Shakespeare Festival Theatre in Stratford, Connecticut, among the many performances I experienced there, the highlight was seeing Morris Carnovsky in the role of King Lear (twice!). To this day, I consider this the greatest Shakespeare performance I ever saw and it inspired my devotion to King Lear and Shakespeare in general.”

In 1956, a sensational film, Invasion of the Body Snatchers, was released. Cunningly disguised as a horror-film, it is an allegory of the conformism disfiguring US society, turning citizens into zombies, as HUAC’s Iron Curtain slammed down on independent thought.

Thence emerged what now goes by the terms “Wokism” and “Political Correctness”: once the thought-police had dealt with so-called “Communists,” or whatever, backing into the same tight corner the so-called Right and traditionalists was like taking candy from a baby.

Moreover, something one might readily forget here in Europe: until the year 1965, Apartheid reigned in the USA under the term “Segregation”—and again, amongst the White activists in the Civil Rights Movement, Jews were the majority. Slandered, assaulted and sometimes murdered, these intellectuals, dixit Earl Lively of the John Birch Society, intended to set up an “independent Negro-Soviet Republic”[sic] (Invasion of Mississippi).

As for Cantor’s adolescence in the 1960s, it was marked by a series of murders designed to throw open the citadel to the Strangeloves: John F. Kennedy (November 22, 1963); Malcolm X (1965), Robert F. Kennedy and Martin Luther King (1968), and a host of small-fry such as Jack Ruby, “disappeared” for having gleaned bits and pieces of the puzzle.

The Articles of Faith, 1536—2022

As a subject of His Britannic Majesty, the author of these lines is well-acquainted with the leaden cape cast over the Kingdom since Henry VIII and his Articles of the Faith (1536) which were imposed by extortion, intolerance and violence. A Kingdom, where since the theocrat Henry, freedom of thought and political action have lived on only in Shakespeare’s theatre.

Although the USA may for a moment in history, have been a temple of liberty, since that day at Hiroshima in 1945, the people of the USA have cowered in a Don’t-Go-There mind-set, feverishly seeking to comply with whatever the day’s Articles of the Faith may enjoin.

Accordingly, and without pressing the point, I would venture to suggest that Paul Cantor may have unconsciously sought shelter under the wings of a clique seen as both fearsome and eminently respectable. And as Cantor lived in the cool shade of the Ivy League’s ivy leaves, he had never to confront in person the reality of the dead, the mutilated, the bankrupt, the exiled, strewn in the wake of his self-satisfied, war-mongering friends.

In Europe, the academic milieu, leaning “centre-left,” appears to have resolved to stonewall a Shakespearean who, unlike his more duplicitous colleagues, owned very frankly to such untoward acquaintances. Error! For Paul Cantor—another enigma—is amongst the few who have understood why Shakespeare wrote what he did, and among the few who have inspired tens of thousands of youths to serious study.

Academic, and Mountebank

To his students, Paul Cantor was an interpretative artist like Dinu Lipatti or Pau Casals; he neither “explained” Shakespeare, nor “criticised” him, but tried to think his way into his thoughts.

In the best sense of the term, Cantor remained a child all his life, gazing at the world through the eyes of his idol. He rejoiced like a child at a student’s awkward question; riding the waves of his idol’s ideas, he cheerfully took a slap in the face whenever Shakespeare wrecked a fond neo-con belief. When William Kristol asked whether Shakespeare might be neo-con compatible? Cantor retorted—no—would have been nice, but Shakespeare will not be pigeon-holed.

As mountebank, Cantor, who wrote extensively on US television, had seen classical theatre collapse through lack of subsidy and an apprentice-system, and had realised that for his own lifetime, the class-room would have to be the theatre, and the professor, an actor on that stage.

The groundlings standing on their own two feet before the stage, and who in Shakespeare’s day made up the bulk of the audience—were Cantor’s students, lucky to have access to a master free of cynical utilitarianism. The good news for posterity is that while Cantor’s writings may not perhaps be ground-breaking, his true and irreplaceable contribution, those marvelous in-person seminars where Cantor, thinking out loud, revels in the to-and-fro with students, have largely been filmed.

“Idiocene” or Ideas?

In his life as a Shakespearean, Cantor knew that it was the average citizen’s intellect would decide the fate of the republic. In July, the Italian politician Pino Cabras summarized the point thusly: “though the notion of staking our hopes on the optimism of will-power may be attractive, I would nonetheless suggest that this crisis is without precedent, and that consequently, the ruling classes, frightened out of their wits, will concede nothing, not an inch. Meanwhile, those who object to their rule suffer from backwardness, be it cognitive, cultural or political, while we are the ‘first generation which cannot afford to make mistakes.’” (See also Teresita Dussart). Taking on that backwardness was Cantor’s mission, and this is what he said of his 40 years’ teaching:

“…the only thing I teach where the students continue to respond with the same enthusiasm is Shakespeare. With other things, things vary in time—and you can see trends and fashions—but Shakespeare is a sure-fire hit. Shakespeare doesn’t need our help. You know it’s John Milton, Geoffrey Chaucer, they need our help; that’s where you see the curriculum collapsing.

“Shakespeare stands on his own two feet and basically you can’t keep students away from Shakespeare courses. They’re the most heavily enrolled at the University of Virginia… The poetry is so beautiful, the drama is so powerful, and they all can relate to it on some of the most basic levels.”

(Of course, Cantor refrains from concluding that it was his seminars that had students piled to the rafters).

Cantor, an Anti-Exceptionalist on the US Island

Through Cantor’s study of Shakespeare, he came to see that the USA was a sort of island, remote from the realities of this world, and that his students needed to grasp this as a peril rather than a privilege: “Shakespeare understood that different forms of government shape different kinds of people … his Romans are different from his Englishmen and in fact his Republican Romans are different from his Imperial Romans. He understood that not all human types are available at all times. So, for example, he’s very aware of how living in a pagan republic as his characters do in Coriolanus is very different from living in a Christian monarchy as, say, his characters do in his history plays.”

Thus, in Cantor’s seminars on the Venetian plays—Othello, The Merchant of Venice—he notes that Shakespeare weighs arguments asserted variously by Muslims, Jews and Christians. Taking no sides, he scrutinises the impact on public life of each thought-system, comparing Venice, a thoroughly oligarchical republic practising religious tolerance for commercial motives, to the tottering theocracy of Elizabeth I, as the latter took the worst possible path to stabilise the state, i.e., empire-building.

In so doing, Cantor led his students to wonder whether their own, American personality, sprung from a given time and place in the reign of imperial exceptionalism, might truly be an Ideal of Man, in an Ideal State?

“Not all human types are available at all times” … Quite. But would the American Regina Dugan perhaps be a latter-day replica of the condottiere Gilles de Ré? A point to ponder.

Monarchist? Republican?

Which brings us to the republican question. From Cantor’s standpoint, neither was Shakespeare Calvin, nor England, his Geneva:

“Now, traditionally in literary criticism, people assume Shakespeare was an uncritical supporter of the English monarchy. I think he really was thinking about the monarchy and how it might be reformed.… I think he understood the greatest defect of monarchy was succession. That no matter how good a king might be, there was no guarantee that his son or daughter would be equal.… Moreover, I think Shakespeare was interested in the way being brought up to the throne is a corrupting influence, and something he shows about Richard II, and much of the Henry IV plays, I think, are designed to show how a king might get a good education.

“So, I don’t think Shakespeare was an uncritical supporter of monarchy as a form of government in the abstract.… he shows an unusual interest in republics for someone who’s supposed to be just supporting monarchy.

“I think that Shakespeare is accepting the fact that England is a monarchy. He’s not going to try to bring about a revolution and institute a republic … But he was interested in how could we reform the monarchy and maybe move it more in the direction of a republic? And that I think is the key to the story of Henry IV and Henry V.”

The Professor remarks that Shakespeare was well aware of the keen interest with which the élite, up to the Monarch herself, followed his plays (on Richard II, Elizabeth I famously declared in private conversation “I am Richard, know you not that?”), and that accordingly, his scrutiny of Rome’s systems of government from the primitive Republic (Coriolanus), to its fall and the premises of Empire (Julius Caesar) and the Empire itself (Anthony and Cleopatra) would—eventually—most likely have political repercussions.

To Cantor, Shakespeare is a tough realist, who saw England as too immature politically for a republican revolution in his time without smashing the crockery; pig-headed and pitiless, Malvolio in Twelfth Night is a kind of premonition of Oliver Cromwell, dictator. Conversely, how might one sow the seeds of an ideal republic and throw a few sops to the nobility, without cracking the State’s foundations? Can this succeed with a starving, desperate, dangerous people? In Coriolanus, Shakespeare concludes that where a purportedly republican élite holds its own people to be “rabble,” they will give the State over to treachery, civil war and war. A state of affairs we are currently come up against.

Philosopher in a Clown Suit

Despite being surrounded, some might say fenced in, by neo-cons entangled with a certain small state in the Middle East, Professor Cantor was anything but a Professional Jew, and he always refused to howl with the wolves. Few save Cantor have noted that in The Merchant of Venice, the Christians are depicted as liars, hypocrites and self-righteous in their cruelty, whereas Shylock unashamedly advertises his nastiness. Translated into Yiddish in 1900, the play had the great Jewish actors all vying to play Shylock, including the aforesaid Morris Carnovsky.

Cantor had no time for the ludicrous authorship controversy. Perusal of the abundant and coherent documentation and especially, the internal evidence, left him in no doubt that William Shakespeare wrote Shakespeare. In this context, we cannot resist quoting Robert Gore-Langton’s delightful article on the launch of Shakespeare North; here he is questioning the Trust’s Chairman, Edward Stanley, Earl of Derby: “Is there any belief in the family that Shakespeare was actually a cover name for the 6th Earl of Derby, as some believe? The short answer is an emphatic no. “I once asked my uncle and he said: ‘have a straightforward answer to that: we could have never been bright enough; it couldn’t have been any of us.’”

Bright, Paul Cantor certainly was. In an essay he penned in 2014 on Arthur Melzer’s Philosophy between the Lines, intitled “Philosophy in a Clown Suit,” and which I came across only after formulating the thoughts above on his double life, Cantor appears to give us the key:

“Imagine, then, the plight of philosophers who commit their dangerous thoughts to writing and thereby threaten to publicize their disagreements with the political and religious establishments. Philosophers had to learn an art of writing that would enable them at one and the same time to conceal and reveal their thoughts—to conceal their unorthodox ideas from a potentially hostile public and yet reveal them to like-minded, potential philosophers whom they wished to develop as students. The result was the famous ‘double doctrine of the ancient philosophers.’ They learned to write in such a way that their works had an exoteric and an esoteric meaning, a conventional meaning on the surface that would placate would-be censors and persecutors, and an unconventional meaning tucked away between the lines.”

Mendelssohn Moses is a Paris-based writer.