On the completion of his studies at Königsberg in 1764, Johann Gottfried Herder accepted a position as a tutor in Riga, and was a preacher to local congregations in the vicinity of the Baltic city beginning in 1765. His time in Riga gave Herder the leisure and opportunity to involve himself in contemporary debates on literature and philosophy. It was in this way that he became familiar with the philosopher and author Thomas Abbt. Abbt was part of the Friedrich Nicolai circle, and wrote articles for the Briefe, die neueste Literatur betreffend, which Nicolai edited together with Gotthold Ephraim Lessing and Moses Mendelssohn between 1759 and 1765. Abbt was appointed professor of mathematics at the University of Rinteln in 1761, and held various administrative posts at the court of Count Wilhelm zu Schaumburg-Lippe from 1765 onwards. Herder’s engagement with Abbt’s philosophical views occupies a central position in the fragmentary treatise on contemporary German literature, Ueber die neuere deutsche Literatur (1766-67) [On Recent German Literature], which made Herder a household name among the German reading public. When he learned of the sudden death of Abbt, only six years his senior, in 1766, Herder wrote to Nicolai, “Abbt’s death is an irreplaceable loss for Germany. If there were ever an author who could consume me with his mood and way of thinking: it was Abbt and his writings.”

In the course of the following year, Herder came up with a plan to erect a “written memorial” to Thomas Abbt. The idea was not merely to pen an appreciation of a single individual, but to extend his reflections on Abbt to include two other recently deceased writers whose works had influenced Herder and whose thinking he wished to develop further: Alexander Gottlieb Baumgarten and Johann David Heilmann. Herder decided to write a three-part obituary, devoted in equal measure to the memories of Abbt, Baumgarten and Heilmann as thinkers whose loss was untimely yet whose work could be continued and completed by others.

Throughout 1767, Herder worked on the portrait of Abbt and also produced some drafts for this more comprehensive concept, as well as some fragments of the memorial to Baumgarten. However, he was

dissatisfied with the piece on Baumgarten and soon turned to other projects. Only the first part of the Thomas Abbt obituary was published, under the title Ueber Thomas Abbts Schriften, der Torso von einem Denkmal, an seinem Grabe errichtet, Erstes Stuck [On the Writings of Thomas Abbt, the Torso of a Memorial Erected at his Graveside, Part the First], in early 1768.

Herder prefaced the reflections on Thomas Abbt with an extensive prologue and introduction. In the prologue, he referred to the original idea of a threefold memorial and discussed the necessity of engaging with the minds of the dead, as they lived on in their works. The introduction outlines the method of the treatise, and as such constitutes a statement of Herder’s biographical concept. He refers to the “art of portraying the soul of another,” an art which underlies any authentic depiction of the biographical subject. Only in the third part of the Torso does Herder come to deal in detail with Thomas Abbt, his works and his style. The priority he gives to theoretical questions surrounding biography, over and above the specific discussion of Abbt’s life and works, can be understood as an effect of the original plan to include Baumgarten and Heilmann—the tripartite obituary would have called for more generally applicable reflections on biographical portrayal. The prologue and introduction however stem from a desire to review critically the traditions of obituary and appreciation, and to reflect afresh on the conditions and possibilities of biographical writing.

In the following pages, I wish to demonstrate with reference to the Torso that biography serves Herder not only as a means of affirming a successfully completed life-course, but also as a medium of intellectual engagement with a variety of political, historical, theological, anthropological and aesthetic issues. Herder expands the thematic and discursive scope of the genre beyond the recounting of the life story, thus setting the course for the development of biographical writing in German throughout the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.

1. Re-animation

“[T]he desire to speak with the dead” has long been a central motivation of both literary studies and historical research, from Herder’s time to that of the New Historicists. This notion of literature and history as an act of communication between the living and the dead, a kind of mediation, is particularly relevant to the modern conception of biography. The re-animation of the souls of the dead through the act of remembrance was a key motivation in Herder’s understanding of biographical writing. In his Briefe zu Beförderung der Humanität [Letters for the Advancement of Humanity], Herder writes:

Lass Tote ihre Toten begraben; wir wollen die Gestorbnen als Lebende betrachten, uns ihres Lebens, ihres auch nach dem Hingange noch fortwirkenden Lebens freuen, und eben deshalb ihr bleibendes Verdienst dankbar fur die Nachwelt aufzeichnen. Hiermit verwandelt sich auf einmal das Nekrologium in ein Athanasium, in ein Mnemeion; sie sind nicht gestorben, unsre Wohltäter und Freunde: denn ihre Seelen, ihre Verdienste urns Menschengeschlecht, ihr Andenken lebet.

[Let the dead bury their dead; we will consider the departed as living, will rejoice in their life, which continues to affect us after their departure. With gratitude will we set down for posterity their lasting achievement. Thus shall the Necrology become an Athanasium, a Mnemeion; they are not dead, our benefactors and friends: for their souls, their achievements and contributions to humanity, their memory lives on.]

For Herder, biography involves more than the mere description of a life. It is rather a medium which carries life within it and, more importantly, transmits living knowledge, serving in this way to enliven the minds of its readers. The biography of Thomas Abbt claims to present the reader with his spirit, which lives on after the death of his body. Herder characterises the process of transmission from the biographical subject through the biographer to the reader by means of an eloquent metaphor of animation, wherein the dead author’s mind is not only re-animated by the biographer but where the encounter with Abbt’s spirit also breathes new life into the reader. Here Herder has recourse to a vein of metaphor that can be traced to the creation story of the Old Testament, as well as to the Homeric epics: the soul as the breath of life, which can be inhaled or exhaled. In the Old Testament, it is the breath of God which gives life to all creatures. By contrast, Homer uses the idea of pneuma, which later comes to stand for the soul, to refer exclusively to that power which departs from humans when they faint or die. The thinking, feeling soul is not originally encompassed by this concept. Herder uses soul in the archaic sense of “breath of life” in his study of Thomas Abbt. Abbt’s mind (Geist) can survive the death of his body and continue to exist in the “spirit world,” ultimately exerting an animating influence, like the “breath of life” in the Old Testament.

To illustrate this animation process, Herder uses two further metaphors, magnetism and anointment. Human souls—here Herder alludes to Plato’s dialogue Ion—can exert “power” over each other, much as magnets do. Plato used this comparison to explain poetic inspiration, and for Herder, too, the ideas of “power” and “force” (Kraft) are particularly relevant to the aesthetic sphere. The animating spirit of the deceased is a creative force that does not ebb away after death, but can be transferred to others, to the living. For this transfer to occur, however, the spirit (Geist) of Thomas Abbt must be located in his written legacy, in the corpus of writings he has left to posterity, and liberated from the “husk” of “dead words.” An “ointment” with which to anoint the writer’s intellectual successors can, and should, be distilled from the writings—the implication being that this is the biographer’s main task. Before the animating influence of the deceased’s spirit can exert itself, it must first be extracted from the writings by a capable hand. The metaphor points to the biographer’s hermeneutic role, which consists in the selection, interpretation and explanation of the subject’s writings with the aim of distilling that person’s thought and transmitting its essence to the reader; this is undoubtedly how Herder conceived his own task with regard to the legacy of Thomas Abbt.

Throughout the treatise on Abbt, Herder’s reflections on the performative aspect of biographical practise are closely connected to the questions of life and death. Abbt’s death is, according to Herder, not so much the culmination of his life as the starting point for a fruitful engagement with the scholar and his writings. Herder draws on the traditions of graveside oration and written obituary, but he also departs from these traditions in significant ways.

In the opening words—”Ich trete an das Grabmal eines Mannes” [“I approach the tomb of a man”]—Herder evokes the tradition of the funeral oration, imaginatively situating his own text at the graveside of the deceased, he recalls a rich and extensive literature on death and mourning. In the seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries, funeral addresses or funeral sermons in printed form enjoyed widespread popularity in Germany.

The structure and content of these texts was strictly determined by established rhetorical norms. In contrast with later customs, the funeral oration of this period was not intended to express emotions of loss and grief, but rather to generate these affects by means of a concerted use of rhetoric. The emotion of grief was seen as a deliberate consequence of the oration; as such, it lay within the control of the speaker.

Furthermore, just as the oration was supposed to generate grief, so too was it intended to bestow consolation; the offer of comfort and hope as a way of overcoming grief was built into the performative concept of the speech. Thus, Grief, as a state of emotional excitation, is considered to be less an affective reaction to the death of another than an effect produced by language and rhetoric. While the funeral sermon of the Baroque period emphasised the affective, consolation bringing elements of speech—movere—by the time of the Enlightenment, the didactic aspects of the eulogy—docere—were considered to be of foremost importance. During the latter period, remembrance of the dead serves above all as an appeal or admonition to the living.

Biographical narration in German takes on a new significance insofar as it can contribute to an Enlightenment program of Bildung: in the vita of the Enlightenment eulogy it is not death, but rather the exemplary life that occupies centre stage. The notion of biography as a kind of practical guide to living becomes, in the Enlightenment period, a way of legitimising the genre for the rising middle class. At the level of performance, the perlocutionary intention of the obituary shifts from the regulation of the affects to the affirmation of a bourgeois ideal; the aim of the memorial speech is no longer emotional consolation, but instruction, guided by reason. In the system of Baroque rhetoric, the event of death, mediated by the rhetoric of the eulogy, generated an affective impact; by contrast, during the Enlightenment, the life of the deceased itself becomes a didactic text. Among other things, the changes in the genre of the obituary from the Baroque to the Enlightenment make manifest the transition from a “rhetorical” to a “hermeneutic” culture in Europe.

Herder realises the full import of this ongoing transition in biographical discourse. The praise of rulers dominated biographical writing in the Baroque period, but the bourgeois career becomes the paradigm for the Enlightenment; accordingly, Herder focusses primarily on the biographies of writers and scholars. He develops principles of biographical reading that allow for an integrated approach to life and work, so that a “living” portrait of the writer can be drawn from both, thus providing a model for future lives and writings. In this way, Herder’s program of Bildung departs not only from the Baroque but also from the rationalist model of the early Enlightenment, which was determined by abstract scientific and aesthetic concepts. For Herder, the life and individuality of exemplary figures provide crucial orientation for the process of Bildung.

Another way in which Herder breaks with the early Enlightenment is through the greater significance he accords to emotions in biographical discourse, revealing his debt to key concepts of sensibility or Empfindsamkeit, concepts such as the ‘language of the heart” or “sympathetic communication.” Underlying these concepts is the idea that the emotional and mental world of the individual person could flow without rupture into the text and be authentically contained by it. The paradigmatic expression of this idea can be found in Christian Fürchtegott Gellert’s instructions to letter writers. Influenced by English epistolary novels, Gellert calls for a Herzenssprache which could facilitate the sympathetic rapport between two individuals through the communicative medium of the letter. This idea, so central in the German context not only to the Empfindsamkeit movement but also to the cult of genius in the late 18th century, occupied a decisive position in Herder’s understanding of biography. The Baroque regime of the affects is reversed: it is no longer intended that the text should induce mourning. Rather, Herder follows a modern understanding of the affects, in that he locates the necessity for biographical memorialisation in the mourning for the dead. The sentiment itself is taken as read, and not subjected to critical scrutiny. In this sense, emotions form the basis of communication in Herder’s biographical concept: the mourning of the dead unites biographer and reader in a community of loss.

The biographer sees his work as a “gift of love” only through “loving enthusiasm” can he fulfil the expectation that the biography provide a faithful portrait of the deceased. He describes this approach in erotically charged language which draws on numerous topoi of love poetry while pointing to a key problem of modern biography, namely its inherent voyeurism. He writes of the necessity to “watch for those moments in which the soul disrobes and reveals itself in its enchanting nudity, like a beautiful woman: so that we may nestle against the other’s way of thinking and learn wisdom as if through a kiss.” Emotion is in these terms no longer an effect of speech, but rather the fundamental condition for communication and understanding. What we are dealing with here—as Herder emphasises—is an encounter mediated through the printed word. The works of an individual—in the case of Thomas Abbt, the man’s philosophical and political writings—bear authentic witness to his soul; attentive and intelligent reading provides access to the “naked,” thus “authentic” soul of the author. The biographer is first and foremost a reader, in keeping with the Herderian concept of authorship, which is indissociable from readership. His own authorship is secondary and serves as a vehicle for transmitting the biographical subject’s spirit to a broader public.

As in all of his writings, Herder emphasises in his biographies the significance of living insight, which derives both from contemplation and sense impression. It is the combination of the author’s creativity with the imaginative powers of the reader that breathes life into dead documents and allows them to speak. Herder’s biographical writing reveals the influence not only of the paradigm shift in the area of rhetoric but also of the secularising tendencies of the Enlightenment. In the 17th century, the understanding of death was still embedded in a system of Christian anthropology and religious practice; death was seen as a passage from one world to the next. The anthropology of the Enlightenment, with its focus on this world rather than on the world to come, undermines this traditional concept of death. Fundamental questions arise: is there life after death? What vanishes when the life of the body comes to an end—and what remains? Can an “Enlightened” Christianity continue to insist on the immortality of the soul? These questions were hotly debated by German intellectuals in the 1760s. Thomas Abbt himself had commented extensively on these issues in a debate with Moses Mendelssohn and it thus comes as no surprise that Herder’s obituary on Abbt positions itself within this discourse.

In response to the influential German art historian Johann Joachim Winckelmann’s Gedanken iiber die Nachahmung der Griechischen Werke in der Malerei und Bildhauerkunst [Thoughts on the Imitation of Greek Works in Painting and Sculpture] (1755), Gotthold Lessing published his Laokoon oder iiber die Grenzen der Malerei und Poésie [Laocoon, or the Limits of Art and Poetry] in 1766, initiating a controversial dispute on the representation of emotions in visual arts and literature. Lessing’s publication of Wie die Alten den Tod gebildet [How the Ancients Represented Death] (1769) combined the issue of representation in the arts with the question of immortality. Herder published an essay with the same title in 1774, in which he comments extensively on Lessing and in which his understanding of immortality undergoes several transformations. Herder’s Torso developed in the midst of this aesthetic debate, and must be seen as a predecessor of Herder’s Wie die Alten den Tod gebildet. In the memorial for Thomas Abbt, only one form of life after death is considered: the secular form of immortality guaranteed by the lasting reputation or fame that the dead enjoy among future generations.

Wenn überdem solche Manner aus unvollendeten Planen gerissen warden… alsdenn sollte auf ihrem Grabe die himmlische Stimme schallen, die andere aufriefe, zu vollenden diese verlassne Entwürfe, und da in die Laufbahn einzutreten, wo sie dem andern abgekürzt wurde, um mit einem mal näher dem Ziele zu sein…. Denn das, glaube ich, ist die wahre Metempsychosis und Wanderung der Seele, von der die Alten in so angenehmen Bildern traumen… wenn uns, wie dort Agammemnon ein Traum vom Jupiter in Gestalt des weisen Nestors erscheint; noch wachend seine Stimme in unserm Ohr tonet, und uns aufruft, in ihre Fussstapfen zu treten: wenn alsdenn unser Herz schlägt, und in unsern Adern ein Feuerfunken spruhet, wie sie zu sein! Dies, glaube ich, ist das einzige Mittel, dem Tode zu trotzen, wenn er die Blüten eines Landes abschlägt, damit stets neue hervorkeimen, und er doch endlich sagen musse… siehe! der ist mir doch entronnen.

[When such men are torn from unfinished plans… then the divine voice should echo from their tomb, calling upon others to complete these abandoned projects and thus to join the path at the point where the departed quit it, taking up where they left off…. For this, I believe, is the true metempsychosis and transmigration of souls, that the ancients dreamed of in such pleasant pictures … when to us, as to Agamemnon, a dream of Jupiter in the form of the wise Nestor appears; as we awake his voice still sounds in our ear, calling upon us to follow in the footsteps of these men; when then our heart beats and our blood runs like fire in our veins, to be like them! This, I believe, is the only means of defying death, when it cuts down the flowers of a nation so that others can bud forth and blossom in their stead, so that Death is forced to say: behold! these have escaped me.]

The individual—in the case of Thomas Abbt, the scholar or writer—lives on after the death of his physical body in his intellectual corpus, his works; and not only does the author’s spirit live on in his works, it also becomes capable of animating or enlivening his readers. This is the role of biography in this context, according to Herder. The biography is the voice that calls us to follow the paths trodden by the dead while they lived; the biography is Jupiter appearing to Agamemnon in the guise of Nestor. More prosaically, biography is a means of mediation between author, text and reader. Biography is called upon here to do much more than merely reiterate the external details of a person’s life. The scope of biography is expanded by Herder beyond the traditional practices of eulogy, obituary and funeral oratory, to become the “art of representing the soul of the other.” It is no longer merely the life story of the individual that interests Herder, but rather the story of his mental life, or more accurately, the story of his intellectual development. The biography thus has the double task of portraying the Bildung which formed the soul of the subject during his lifetime, and of exerting a formative influence on the reader.

Eine Menschenseele ist ein Individuum im Reiche der Geister: sie empfindet nach einzelner Bildung, und denket nach der Stärke ihrer geistigen Organen. Durch die Erziehung haben diese eine gewisse eigne, entweder gute oder widrige Denkart geformt, zu einem ganzen Körper, in welchem die Naturkräfte gleichsam die spezifische Masse sind, welche die Erziehung der Menschen gestaltet…. Meine lange Allegorie ist gelungen, wenn sie es erreicht, den Geist eines Menschen, wie ein einzelnes Phänomen, wie eine Seltenheit darzustellen, die wùrdig ist, unser Auge zu beschäftigen; noch besser aber ware es, wenn ich durch sie, wie durch eine Zauberformel, auch unser Auge auftun konnte, Geister, wie körperliche Erscheinungen zu betrachten.

[A human soul is an individual in the realm of minds (Geister): it senses in accordance with an individual formation (Bildung), and thinks in accordance with the strength of its mental organs. Through education these have received a certain either positive or negative direction of their own, according to the circumstances which formed or deformed in the individual in question. In this way our manner of thought is formed, and becomes a whole body in which the natural forces are, so to speak, the specific mass which the education of human beings shapes…. My long allegory has succeeded if it achieves the representation of the mind of a human being as an individual phenomenon, as a rarity which deserves to occupy our eyes. But it would be even better if, through this allegory, as through a magical spell, I were also able to open our eyes to see, to observe, minds as if they were a form of corporeal phenomena.]

2. Biography, the Author and the Soul

The biographical concept sketched here by Herder could well be described as intellectual biography, a concept differentiated from mere literary criticism by the emphasis it places on the soul. In his text Uebers Erkennen und Empfinden der menschlichen Seele [On the Cognition and Sensation of the Human Soul] (1774), Herder shows that the human mind and human reason cannot be separated from the world of the senses and thus do not transcend time; rather, in the form of each individual soul, it undergoes a specific development, being shaped and influenced in crucial ways by the world in which the individual lives. Herder’s explicit intention is to sketch Abbt’s character and to draw on his writings to create a unique portrait of his soul and its development, since within Abbt’s works lies his creative power, the genius of his soul. This genius precedes the works and generates them.

It may seem as if the works themselves are the sole means by which the reader can gain access to the soul of the author. However, one has to bear in mind that the image a biographer can generate in a biography is a fictional construct. Herder thus speaks of the “art” of depicting the soul, well aware that this portrait will only ever be one representation of the deceased. Concepts of authorship in late eighteenth-century Germany are rooted in the idea that the creative mind of the author shines through the literary text. This valorisation of the authorial figure, beginning in Germany with Klopstock and central to the poetics of Empfindsamkeit, Sturm und Drang and to Weimar classicism, proceeds through a projection—often deliberate—of textual and rhetorical phenomena onto the person of the author. A perfect love poem, under this view, could only be produced by a loving mind. Herder’s understanding of biography is founded on the same assumption. From the deeds of a man we can deduce his character, and an image of the writer’s soul can be deduced from his writings. The concept of biography underlying Herder’s text on Thomas Abbt thus stands in a relationship of tension to both author and work. It is an approach that goes beyond the more conventional biographies of writers, biographies which seek merely to interpret the literary work with reference to the author’s life. Herder’s understanding of the relationship between author and work is considerably more complex than that suggested by the biographical fallacy: that the genre of literary biography derives its legitimacy from the existence of the author’s writings.

In addition, for Herder, the biographer himself must experience some emotion for his subject: “Does it not take a small degree of loving enthusiasm to imprint one’s man in the imagination so deeply that one can afterwards bring forth his image, as if from one’s head?” Biography thus presupposes reception to a certain extent. In an inversion of the process of literary production, here the concern with the writings necessarily precedes the concern with the person of the writer. Admiration of literature relates in the first instance to the text and only indirectly to the person who produced it. However, Herder’s text on Abbt emphasises that the aim of engaging with the literary work is to “unlock” the specific “mind” [Geist] of the author. A constitutive assumption of Herder’s biography is that writing can be “made to disappear,” that texts can become transparent and render visible the “soul” of their author. The paradox of the “dead author” and the “transparent text” can only be resolved if the constructed character of that which Herder refers to as the author’s “soul” is acknowledged. The author’s soul, according to Herder, can be found in the textual traces left behind by the physical author after his death. This recalls Klopstock’s notion of the “Auctor,” which involves the projection of rhetorical phenomena onto the figure of the author. Herder introduces this concept into biographical discourse with reference to the author’s “soul.” The authorial soul, speaking through the text to the reader, binds the text to the real, physical Thomas Abbt. The narrative of the life-story thus serves as a thread of continuity through the work of the author. At the same time, the question of the soul’s immortality is resolved: the construct of the soul, conceived of as immortal, can survive the physical death of the author.

3. Biography as Dialogue

The part of the Torso intended to introduce Thomas Abbt begins with the familiar topos of describing his life, but does not offer a detailed account of Abbt’s background, childhood and education, turning instead to the subject’s role as scholar: “The birth of Thomas Abbt contributed without doubt to the fact that one can see him as a writer for humanity, a wise man for the common people.” Abbt was the son of a wig-maker, and as such not patently predestined for a career in letters. Herder thus sees him as a mediator between the academic sphere and the world of the common man. This vision of Abbt leads Herder to explore in more detail the relationship between a scholarly education and the more mundane spheres of everyday life. He considers whether the forces of education and academic learnedness might not in fact be detrimental to “sound common sense in the matters of common life.” He then proceeds to Thomas Abbt’s preoccupation with classical literature, introducing a motif that will later to develop into a key Herderian theme: the question of how historical knowledge is relevant to the present. Abbt, according to Herder, did not merely copy the model of the ancients, but rather learned from them, teaching himself according to their style but without disregarding the question of contemporary relevance:

Wenn ich gesagt habe, dass Tacitus und Sallust unserm Abbt den Geist der Geschichte eingehaucht: so meine ich ja nicht, dafi seine Welthistorie eine Sallustianische und noch minder eine Geschichte des Tacitus zu nennen sei: ich schreibe es ihnen bloss zu, dass sie Abbt Geschmack an der Historie und jenen Reflexionsgeist eingeflösset, der sich in alien seinen Schriften aüssert; denn wie Sallust und Tacitus über Begebenheiten und Personen philosophieren, um sie zu beschreiben und zu erklären; so philosophiert er iiber Wahrheiten und Erfahrungen, um sie zu erläutern und zu beweisen. Er wollte aber vom Tacitus und Sallust noch mehr lernen: wie sie zu schreiben.

[When I say that Tacitus and Sallust breathed the spirit of history into our Abbt, then I do not mean that his World History can be called Sallustian, less still a History of Tacitus: rather, I attribute to them the taste for history and reflective spirit imbued in Abbt, which expresses itself in all his writings; for in the same way as Sallust and Tacitus philosophise about events and personages in order to describe and explain them; so too does he philosophise about Truths and Experiences, in order to elucidate and demonstrate them. He wished to learn still more from Tacitus and Sallust: how to write as they do.]

Later in the course of the text, Herder asks how a German author—he sees Abbt very much in these national terms—can best relate to language and culture in general. He maintains the importance of learning from other nations and their authors, whether historical or contemporary, while at the same time bearing in mind the particularity [das Eigensinnige] of each language, culture and epoch. In Herder’s view, Abbt died before he could achieve this synthesis of ancient and modern, old and new. Yet the path towards this goal, a path Herder would seek to travel in a lifetime of writings, was indicated by Abbt in his work. In the final part of the treatise, Herder deals with Abbt’s various philosophical positions, particularly the latter’s position regarding the integration of the national question with theological issues: “Abbt wishes to prove that love of the fatherland enjoins to a fear of death: he does so in a way that shews that only religion can raise us above the horror of the grave.” Here as elsewhere, Abbt’s style and method provide the starting point for Herder’s further reflections. Thomas Abbt frequently illustrated his political and philosophical commentaries with comparisons to Biblical narratives. Herder defends this method, emphasising again the contemporary relevance and usefulness of historical knowledge. Biblical motifs in particular, because of their vivid expressiveness and general familiarity, provide an effective backdrop for philosophical discussions.

Though Torso constitutes an attempt to present the primary elements of Thomas Abbt’s thinking, Herder nevertheless finds room therein to set forth his own convictions. In later texts, Herder uses the epistolary form as an appropriate medium for a “lively” or animated exchange of ideas; similarly, the appreciation of Thomas Abbt takes the form of a dialogue with the deceased. In the living portrait of Abbt which Herder seeks to convey, the biographer himself is also vividly present.

An examination of the life and work of the scholar Abbt becomes for Herder an occasion for exploring a broad range of topics: pedagogy, style, national identity, and religion, among them. The popularity of the biographical sketch in the eighteenth century results partly from this formal openness and thematic diversity. Herder openly concedes that the “spirit” [Geist] of Abbt, as he portrays it in the Torso, is a construct derived primarily from the works of the deceased, correlating only in certain ways with the real personality of Thomas Abbt. Herder’s biographical concept is thus far removed from a naive, affirmative realism which would aim for the greatest possible correspondence between the literary text and the lived reality; rather, his text and the referential claim he makes for it demonstrate a keen awareness of textual status and intertextual provenance. What might appear from the perspective of realism to be a flaw or shortcoming in the Torso text can be perceived at the literary and rhetorical level as an opening up of new biographical possibilities.

The biographical approach Herder chooses in the Torso allows him to reflect on the relationships between classical and modern languages, the meaning and purpose of literary criticism in scholarly journals, and the forms and conditions of biography. A biographical concept that would uphold a realist presentation of the biographical subject as the normative rule of the genre would judge such reflections as a deviation or digression.

In the Herderian biographical essay, in contrast, these reflections constitute an integral component of the biographer’s subjective response and a legitimate expression of the thinking mind. The key to understanding Herder’s biographical concept lies in the question of knowledge transfer. Current theories of memory, such as those advanced by Jan and Aleida Assmann, differentiate between knowledge stored in an archive, understood as a mere repository, and the functional or affective processes of cultural memory. Aleida Assmann designates these two forms of memory with the German terms “speichern” versus “erinnern.” As far as Herder was concerned, simply to store or archive the sum of human knowledge would result in dead, unused knowledge. Herder proposed an alternative approach to knowledge, one that would activate and even animate it, and this idea lies at the core of his understanding of intellectual biography.

Biography can succeed in personalizing abstract knowledge: it is no longer the dead cipher, but a living voice that speaks to us from Thomas Abbt’s works. As Gerhard Sauder has pointed out, the project of a “European literary history” and the related concept of “world literature” [Weltliteratur] is a key concern throughout Herder’s works. Herder’s invention of intellectual biography not only lays the foundations of a biographically-based literary historiography, but opens the prospect of a global history of the mind:

Eine Geschichte der Schriftsteller… welch ein Werk wäre sie! Die Grundlage zu einer Geschichte der Wissenschaften, und des menschlichen Verstandes.

[A history of writers… what a work that would be! The foundation of a history of sciences and of the human intellect.]

Biography becomes in this way a medium through which Herder can engage with a broad range of issues, as can be seen most clearly in the Briefe zu Beförderutig der Humanität and in his later polemic Adrastea. The biographical sketches that can be found throughout Herder’s work provide him with a framework for the exploration of a variety of philosophical, religious, anthropological, literary and art-historical issues. Herder’s concept of biography will go on to influence biographical practice throughout the 19th century. The scope of biography will expand to accommodate questions spanning the entire range and complexity of human culture, but with each individual work still being held together by the unity of the specific biographical subject.

Tobias Heinrich is Lecturer (Assistant Professor) in German at the University of Kent. He is the author of Leben Lesen: Zur Theorie Der Biographie Um 1800 [Reading Life: On The Theory Of Biography Around 1800]. This article was first published in Lumen, 28 (2009), 51–67, and translated from the German by Professor Caitríona Ní Dhúill (University of Cork).

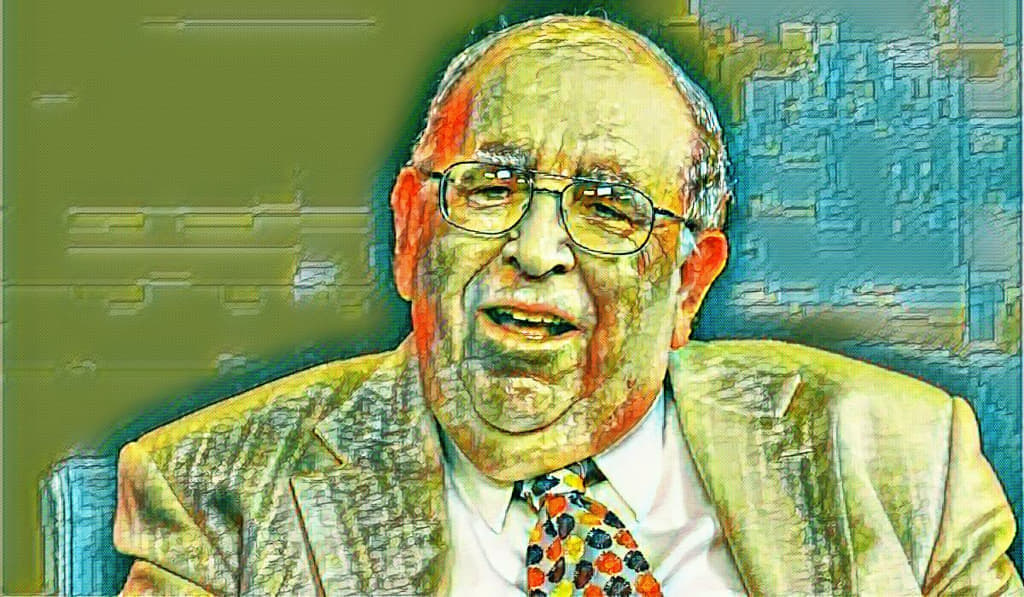

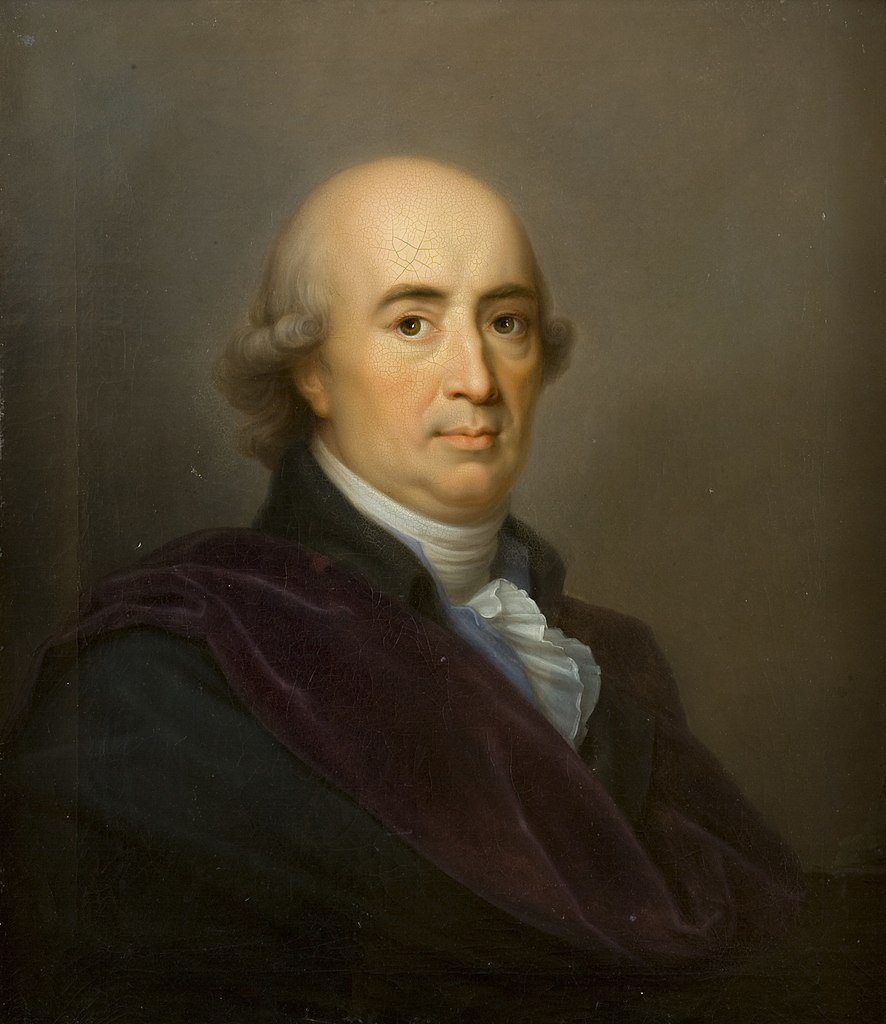

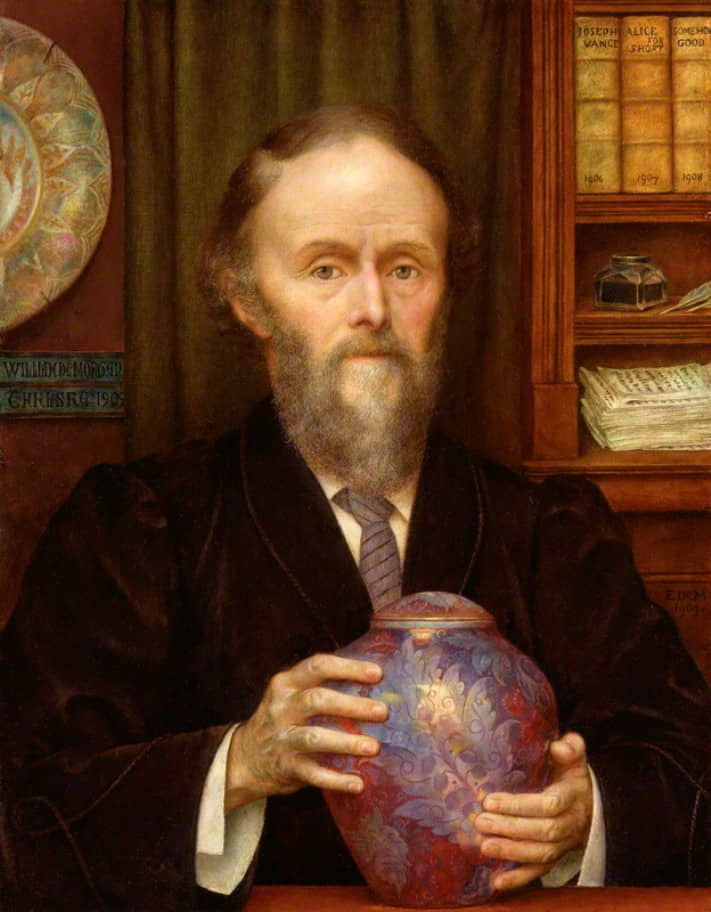

Featured: “Portrait of Johann Gottfried Herder,” by Gerhard von Kügelgen; painted in 1809.