A phantom haunts the ruins of technomorphic and pantoclastic civilization: it is the new species of Homo Resiliens. Freed from the remorse of an unhappy conscience and satisfied with the misery of the reified present, the “last man” dedicated to resilience knows nothing great to fight for and to believe in, to strive for and to hope for. Child of postmodern disenchantment and the end of the belief in grands récits oriented towards a redeemed future, the Homo Resiliens is content with what there is because he thinks it is all there can be. His is an ontology as primitive as it is depressive, which resolves possibility in the given reality, the future in the eternal repetition of the present. Conforming himself to the vulgar pleasures offered to him by the civilization of consumption (“one desire for the day and another for the night,” it is suggested in Thus Spake Zarathusta), the last man of resilience has no supérstite resource of value to oppose to the nihilistic maelstrom, which has exhausted all meaning and abandoned the godless world to the nothingness of production and exchange as ends in themselves.

A desperate expression of a purely passive nihilism, a serial member of an amorphous and shepherdless flock, Homo Resiliens views with the icy pathos of distance every yearning for true freedom, every project for the renewal of the world—he is convinced that this is no longer the time and that, in the twilight era of the decline of idols, there is no other way than conciliation and adaptation to an order of things that, however much it is questioned, admits of no alternatives and no escape routes. The imperative of ne varietur is accompanied, almost in a compensatory way, by a hypertrophic work on the self, aimed at making it more mature and stronger so that it is finally ready to accept without blinking whatever it is.

In the physiognomy of the last man, the most vulgar mediocrity imposes itself as the dominant factor, one perceives the integral contraction of the creative power of the human essence, now devoid of enthusiasm and passion—the Resilient Men, “wretches, who never lived” (Inferno III, v. 64)—resign themselves to what is there, adapting themselves time after time and striving to silence any inner voice of dissidence that might still subsist. The subversive force of the transformation of reality is expelled by the withdrawal into themselves of the last men, who live economic fundamentalism and its scenarios of ordinary misery as an irreversible destiny to which they pay submissive obeisance. The stoic imperative of amor fati, understood as adaptability to the logic of the real, constitutes the essential recipe of their mediocre happiness, in which the will of individual impotence coexists with the fury of the will of omnipotence of the technocapitalist production system.

The figure in which the new gregarious spirit of the last men seems to be best condensed coincides with that of the servitude volontaire proposed by La Boétie, which could be translated as the obscure desire to serve in order to be left in peace, to be dominated so as not to see the unlimited enjoyment derived from the flow of circulation of services and merchandise interrupted. Unlike the Resister, that is, the naturaliter nonconformist subject with the gregarious spirit and perhaps even willing to associate in revolutionary forms with his species, the Resilient Man fits the prototype of the ideal slave, who does not know he is one and who ignores the existence of the chains he carries or, alternatively, confuses them with unrepentant opportunities for inner maturation.

The hellish “malaise of civilization” sinks its roots in the elimination of both the Ideal and the social bond; and congruently produces the desert landscape of the mass hermits, of the Resilient who, socially estranged, try to survive by adapting, biographically overcoming the systemic contradictions almost as if they were only nuisances of the unreconciled self. The Revolutionary Man lived in the perpetual hiatus between reality and his dreams; the Resilient Man lives in the inextinguishable absence of dreams that allow him to think reality as something amendable.

A smart and elusive concept, elusive and capable of adapting resiliently to any context, resilience is, by right, an integral part of the constellation of new virtues incorporated into the managerial civilization of business—from empowerment to motivational practices, from problem solving to mindfulness—and of that neoliberal governance that has now saturated the world of life, commodifying it and reifying it without restrictions or free zones. It is, first of all, the existential attitude, but then also political and social, today systematically demanded of the subjects of the market civilization; that is, of consumers without a homeland and without roots, without critical substance and—Gramsci would say—without residue of the “spirito di scissione“: the mandate, in the form of an omnipresent imperative, comes mainly through the falsely polyphonic chime of the mass-media system, which is the megaphone of its master’s voice. The latter daily exhorts the sad tribe of the last men, the “lost people” of the shirtless of unhappy globalization, to become docile and submissive, to abandon all inopportune antagonism and all redemptive fickleness: in a word, to become resilient, to work on themselves to rise to the level of the world in which they live; that is, to endure on a daily basis, without the return of red heat, and without extemporaneous awakenings of the “spirit of utopia.”

Therefore, the dominant imperative, reaffirmed urbi et orbi by the cultural industry and by the officials of the superstructures, is the one that preaches the disenchanted adaptation to the existing as the only possible reality (Peter Sloterdijk, “Psychopolitics of Schizoid Society,” in Critique of Cynical Reason). From whatever perspective one observes, the resilient subject seems to be the ideal in vitro product of the system of production and of the totally administered civilization. Following the robot sketched by Antonio Trabucchi in his work, Resisto dunque sono—I Resist Therefore I Am—(2007), the resilient person is optimistic on principle, tends to read negative events as circumscribed and in any case as an opportunity for improvement, continues to believe that he is capable of controlling and governing his own life, and does not see any defeat, however thunderous, as arousing the will to fight to change the order of things.

His fundamental predisposition, congenital or conquered through hard work on himself, is “emotional agility,” that is, a kind of precariousness of emotions and feelings, called to express itself in the ability to adapt chameleon-like to the most diverse contexts and the most adverse situations, finding the right resources and the right spirit each time. Du mußt dein Leben ändern (You Must Change Your Life), the title of a successful book by Peter Sloterdijk, crystallizes in its most effective form the postmodern rehabilitation of the stoic endurance of the order of things and the glorification of the cynical reason of those who, after all, aspire only to their own individual salvation in the midst of collective tragedy.

Metabolizing the systemic imperative of adaequatio to the order of things, elevated to the status of “evidence” to be scientifically determined and stoically accepted, the contemporary Homo Resiliens makes no effort to understand and, even less, to rectify the order of things—it starts from the assumption that in case of conflict between Subject and Object, it is in any circumstance the former—for him alone in this lies the secret of a happy life—that has to adapt to the latter, overcoming the traumas and discomforts that untimely led him to such divergence. The transforming passion open to the future, which belonged to the revolutionaries, is annihilated by this contemporary form of disenchanted adhesion; a form whose ductility, in any case, easily tends to unveil the farce and ideological ballast.

The heroic mot d’ordre of courage and its reasoned indocility (frangar, non flectar) is overthrown by the vile adage of resilience and its unlimited willingness to suffer in silence (flectar, non frangar), pretending that traumas and injustices are to be welcomed as moments of overcoming and as proofs of fortitude. Note, en passant, that the adjective “fragile” has as its root the Latin verb frango, which means “to break,” “to rupture,” “to shatter”: the resilient is, therefore, the “fragile” who, as long as he does not break, adapts himself to everything, becoming liquid in the liquid society and, therefore, assuming “fluidity” as his own essential quality in all spheres.

Nietzsche’s famous aphorism, according to which was mich nicht umbringt, macht mich stärker, “what does not kill me, makes me stronger,” does not seem to be taken as a definition of the spirit of resilience: in fact the resilient is an intrinsically weak subject, whose acting or, better to say, whose practical inactivity arises from the preemptive recognition of the superior strength of the object in front of him. Varying on the Hegelian theme, he is more a servant than a master since, preferring to bend in order not to break, he is unwilling to run the extreme risk of his life in order to reverse the order of things and gain freedom.

Like the trampled grass, which is always ready to return to its position, so the resilient one absorbs the blow each time, probably grateful for the precious opportunity of maturation he has obtained from it. He is required apertis verbis to cultivate that “mental flexibility” which consists, at bottom, in the ability to adapt to everything and everyone, which, not accidentally, represents a not inconsiderable variant of the universal flexibility of the era of precariousness and the evaporation of all figures of solidity—from family ties to labor relations, from links with communities and territories of belonging to grounded and structured worldviews.

In fact, one can do whatever one wants with the motto, “resilience,” since, in one way or another, it adapts to everything—such is, paradoxically, its degree of resilience. A paroxysmal profile of the postmodern liquid self, Homo Resiliens can be so in the psychological sphere, if he overcomes traumas by modifying himself; he can be so in politics, if he adapts himself cadaverously to the imperative of ne varietur, carved in capital letters in the neoliberal theologomenon; there is no alternative; he can also be so in economics, if he manages to make a virtue of necessity, living as opportunities the scenarios of ordinary exploitation and daily inequality proper to the fanaticism of the market.

De Mauro’s Dictionary of the Italian Language explains that “resilient” is one who manifests the “ability to bounce back from difficult experiences, adversities, traumas, tragedies, threats or significant sources of stress, maintaining a sufficiently positive attitude when facing existence.” In short, one who suffers misfortune and gets up as if nothing happened; one who in the face of injustice, instead of rebelling, finds the strength to go his own way, even if this means a daily dose of mortifying abuse.

Variant of the current fanaticism of tolerance, resilience is naturally a psychological profile. But it is also, inseparably, a political behavior in keeping with the era of techno-capital absolutism and the austerity desired by boss groups, jubilant at the prospect of being able to govern oppressed and resilient masses; or what is the same, masses capable of absorbing without blinking and without returning to the red heat, the daily violence on which a system is structurally based whose basic premise is the exploitation and misery of the majority for the benefit of a few. Let us not forget then that, as Federico Rampini (La Repubblica, January 23, 2013) showed, “resilient dynamism” was the slogan launched in 2013 by the World Economic Forum and by Obama—therefore in places and by people who fully inscribed in the order of the neoliberal hegemonic bloc of Atlanticist traction.

The Homo Resiliens falls and gets up potentially to infinity, but without ever questioning the objective world that always makes him fall again. Successor of the ignavo confined by Dante in Hell, the Resilient Man does not hinder the march of the world and, in fact, seconds it in all its dynamics, even if it is the most fiendishly unjust. He does not even condemn it with the weapons of criticism or subject it to scathing interpellation, trapped as he is by the smug satisfaction of having succeeded in working on himself to the point of finally accepting the unacceptable.

The resilient is the helpless self that sees personal hardships but never real contradictions and who, in case of disagreement with reality, prefers the psychologist’s couch to the square of the communal revolution, the variation of the self to that of the not-self, as Fichte would say. Its privileged sphere of action and life is individuality in the shadow of power, the disarmament of any critical spirit and the preventive mutilation of any project for the future. He is the ideal subject of the passive and homologated masses, in which everyone thinks and desires the same thing (since no one really thinks or desires anymore); but simultaneously he is also the isolated individual of the new era of telematic solitudes connected through the Internet and disconnected from reality and its throbbing contradictions that ask to be resolved in praxis.

In short, the Resilient Man is the ideal subject of the reifying prose of the new post-1989 capitalism and, a fortiori, of the very developments it is undergoing in the first decades of the new millennium—Homo Resiliens has treasured the appeals addressed to him from all points of the unified networks by the monopolists of discourse and therefore, via mediata, by the neoliberal oligarchic bloc. He has accepted to be submissive instead of revolutionary, adaptable instead of contesting, and has even internalized the need to change himself in order to adapt to a status quo of whose unchangeability he is intimately convinced. In short, he has chosen to speak the language of his class enemy, believing in progress—and therefore in the uninterrupted sequence of conquests of the dominant groups—and above all meekly assuming the behavior that the masters have always dreamed of from the slaves. Is it not the unconfessed dream of every master to rule docile and submissive slaves, in a word resilient? Is it not true that every shepherd has always had the desire to be able to lead a meek and obedient flock, ready to do whatever he is ordered to do because he is convinced that there is no other possibility?

That is also why resilience is, among all, the most propedeutic quality for the success of the neoliberal oligarchic bloc, the virtue that is propitious and expected from the massa damnata of the defeated. It is an integral part of the new mental order, politically correct and ethically corrupt, which serves as a superstructural complement to the structure of the asymmetrical diagram of the balance of power in the epoch inaugurated with the burial, albeit provisional, of the Marxian “dream of one thing” under the heavy rubble of the Wall (9.11.1989).

Diego Fusaro is professor of History of Philosophy at the IASSP in Milan (Institute for Advanced Strategic and Political Studies) where he is also scientific director. He is a scholar of the Philosophy of History, specializing in the thought of Fichte, Hegel, and Marx. His interest is oriented towards German idealism, its precursors (Spinoza) and its followers (Marx), with a particular emphasis on Italian thought (Gramsci or Gentile, among others). he is the author of many books, including Fichte and the Vocation of the Intellectual, The Place of Possibility: Toward a New Philosophy of Praxis, and Marx, again!: The Spectre Returns. [This article appears courtesy of Posmodernia].

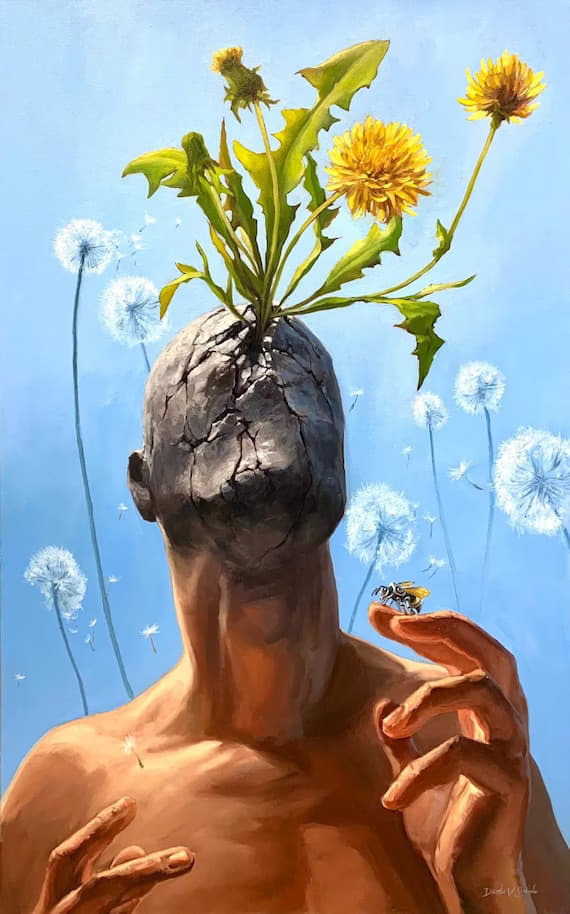

Featured: Resilient Weeds, by Dimitri Sirenko.